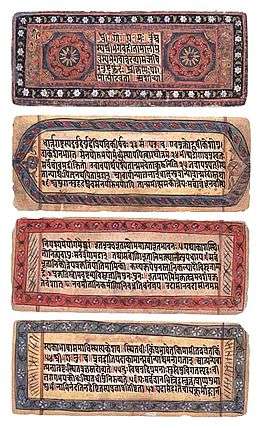

Hindu texts

Hindu texts are manuscripts and voluminous historical literature related to any of the diverse traditions within Hinduism. A few texts are shared resources across these traditions and broadly considered as Hindu scriptures.[1][2] These include the Puranas and the Itihasa. Scholars hesitate in defining the term "Hindu scriptures" given the diverse nature of Hinduism,[2][3] but many list the Bhagavad Gita and the Agamas as Hindu scriptures,[2][3][4] and Dominic Goodall includes Bhagavata Purana and Yajnavalkya Smriti in the list of Hindu scriptures as well.[2]

| Part of a series on |

| Hindu scriptures and texts |

|---|

|

| Related Hindu texts |

|

Timeline |

History

There are two historic classifications of Hindu texts: Shruti – that which is heard,[5] and Smriti – that which is remembered.[6] The Shruti refers to the body of most authoritative, ancient religious texts, believed to be eternal knowledge authored neither by human nor divine agent but transmitted by sages (rishis). These comprise the central canon of Hinduism.[5][7] Of the Shrutis (Vedic corpus), the Upanishads alone are widely influential among Hindus, considered scriptures par excellence of Hinduism, and their central ideas have continued to influence its thoughts and traditions.[8][9]

The Smriti texts are a specific body of Hindu texts attributed to an author,[10] as a derivative work they are considered less authoritative than Shruti in Hinduism.[6] The Smriti literature is a vast corpus of diverse texts, and includes but is not limited to the Puranas , the Hindu epics, the Sutras, the texts of Hindu philosophies, the Kāvya or poetical literature, the Bhasyas, and numerous Nibandhas (digests) covering politics, ethics, culture, arts and society.[11][12]

Many ancient and medieval Hindu texts were composed in Sanskrit, many others in regional Indian languages. In modern times, most ancient texts have been translated into other Indian languages and some in non-Indian languages.[2] Prior to the start of the common era, the Hindu texts were composed orally, then memorized and transmitted orally, from one generation to next, for more than a millennia before they were written down into manuscripts.[13][14] This verbal tradition of preserving and transmitting Hindu texts, from one generation to next, continued into the modern era.

Smriti

The texts that appeared afterwards were called smriti. Smriti is a literature which includes various Shastras and Itihasas (epics like Ramayana, Mahabharata), Harivamsa Puranas, Agamas and Darshanas.

The Sutras and Shastras texts were compilations of technical or specialized knowledge in a defined area. The earliest are dated to later half of the 1st millennium BCE. The Dharma-shastras (law books), derivatives of the Dharma-sutras. Other examples were bhautikashastra "physics", rasayanashastra "chemistry", jīvashastra "biology", vastushastra "architectural science", shilpashastra "science of sculpture", arthashastra "economics" and nītishastra "political science".[15] It also includes Tantras and Agama literature.[16]

This genre of texts includes the Sutras and Shastras of the six schools of Hindu philosophy.[17][18]

Puranas

The Puranas are a vast genre of Hindu texts that encyclopedically cover a wide range of topics, particularly legends and other traditional lore.[19] Composed primarily in Sanskrit, but also in regional languages,[20][21] several of these texts are named after major Hindu deities such as Lord Vishnu, Lord Shiva and Goddess Devi.[22][23]

The Puranic literature is encyclopedic,[24] and it includes diverse topics such as cosmogony, cosmology, genealogies of gods, goddesses, kings, heroes, sages, and demigods, folk tales, pilgrimages, temples, medicine, astronomy, grammar, mineralogy, humor, love stories, as well as theology and philosophy.[19][21][22] The content is diverse across the Puranas, and each Purana has survived in numerous manuscripts which are themselves voluminous and comprehensive. The Hindu Puranas are anonymous texts and likely the work of many authors over the centuries; in contrast, most Jaina Puranas can be dated and their authors assigned.[20]

There are 18 Maha Puranas (Great Puranas) and 18 Upa Puranas (Minor Puranas),[25] with over 400,000 verses.[19] The Puranas do not enjoy the authority of a scripture in Hinduism,[25] but are considered a Smriti.[26] These Hindu texts have been influential in the Hindu culture, inspiring major national and regional annual festivals of Hinduism.[27] The Bhagavata Purana has been among the most celebrated and popular text in the Puranic genre.[28][29]

The Tevaram Saivite hymns

The Tevaram is a body of remarkable hymns exuding Bhakti composed more than 1400–1200 years ago in the classical Tamil language by three Saivite composers. They are credited with igniting the Bhakti movement in the whole of India.

Divya Prabandha Vaishnavite hymns

The Nalayira Divya Prabandha (or Nalayira (4000) Divya Prabhamdham) is a divine collection of 4,000 verses (Naalayira in Tamil means 'four thousand') composed before 8th century AD [1], by the 12 Alvars, and was compiled in its present form by Nathamuni during the 9th – 10th centuries. The Alvars sung these songs at various sacred shrines. These shrines are known as the Divya Desams.

In South India, especially in Tamil Nadu, the Divya Prabhandha is considered as equal to the Vedas, hence the epithet Dravida Veda. In many temples, Srirangam, for example, the chanting of the Divya Prabhandham forms a major part of the daily service. Prominent among the 4,000 verses are the 1,100+ verses known as the Thiru Vaaymozhi, composed by Nammalvar (Kaaril Maaran Sadagopan) of Thiruk Kurugoor.

Other Hindu texts

Hindu texts for specific fields, in Sanskrit and other regional languages, have been reviewed as follows,

Origin of arts and sciences in India

The Hindu scriptures provide the early documented history and origin of arts and sciences forms in India such as music, dance, sculptures, architecture, astronomy, science, mathematics, medicine and wellness. Valmiki's Ramayana (500 BCE to 100 BCE) mentions music and singing by Gandharvas, dance by Apsaras such as Urvashi, Rambha, Menaka, Tilottama Panchāpsaras, and by Ravana's wives who excelling in nrityageeta or "singing and dancing" and nritavaditra or "playing musical instruments").[30] The evidence of earliest dance related texts are in Natasutras, which are mentioned in the text of Panini, the sage who wrote the classic on Sanskrit grammar, and who is dated to about 500 BCE.[31][32] This performance arts related Sutra text is mentioned in other late Vedic texts, as are two scholars names Shilalin (IAST: Śilālin) and Krishashva (Kṛśaśva), credited to be pioneers in the studies of ancient drama, singing, dance and Sanskrit compositions for these arts.[31][33] Richmond et al. estimate the Natasutras to have been composed around 600 BCE, whose complete manuscript has not survived into the modern age.[32][31]

See also

- Hindu Epics

- Hindu eschatology

- List of Hindu scriptures

- List of historic Indian texts

- List of sutras

- Prasthanatrayi

- Sanskrit literature

- Timeline of Hindu texts

Notes

References

- Frazier, Jessica (2011), The Continuum companion to Hindu studies, London: Continuum, ISBN 978-0-8264-9966-0, pages 1–15

- Dominic Goodall (1996), Hindu Scriptures, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-20778-3, page ix-xliii

- Klaus Klostermaier (2007), A Survey of Hinduism: Third Edition, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-7082-4, pages 46–52, 76–77

- RC Zaehner (1992), Hindu Scriptures, Penguin Random House, ISBN 978-0-679-41078-2, pages 1–11 and Preface

- James Lochtefeld (2002), "Shruti", The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 2: N–Z, Rosen Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8239-3179-8, page 645

- James Lochtefeld (2002), "Smrti", The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 2: N–Z, Rosen Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8239-3179-8, page 656–657

- Ramdas Lamb (2002). Rapt in the Name: The Ramnamis, Ramnam, and Untouchable Religion in Central India. State University of New York Press. pp. 183–185. ISBN 978-0-7914-5386-5.

- Patrick Olivelle (2014), The Early Upanisads, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-535242-9, page 3; Quote: "Even though theoretically the whole of vedic corpus is accepted as revealed truth [shruti], in reality it is the Upanishads that have continued to influence the life and thought of the various religious traditions that we have come to call Hindu. Upanishads are the scriptures par excellence of Hinduism".

- Wendy Doniger (1990), Textual Sources for the Study of Hinduism, 1st Edition, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-61847-0, pages 2–3; Quote: "The Upanishads supply the basis of later Hindu philosophy; they alone of the Vedic corpus are widely known and quoted by most well-educated Hindus, and their central ideas have also become a part of the spiritual arsenal of rank-and-file Hindus."

- Wendy Doniger O'Flaherty (1988), Textual Sources for the Study of Hinduism, Manchester University Press, ISBN 0-7190-1867-6, pages 2–3

- Purushottama Bilimoria (2011), The idea of Hindu law, Journal of Oriental Society of Australia, Vol. 43, pages 103–130

- Roy Perrett (1998), Hindu Ethics: A Philosophical Study, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-2085-5, pages 16–18

- Michael Witzel, "Vedas and Upaniṣads", in: Flood, Gavin, ed. (2003), The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism, Blackwell Publishing Ltd., ISBN 1-4051-3251-5, pages 68–71

- William Graham (1993), Beyond the Written Word: Oral Aspects of Scripture in the History of Religion, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-44820-8, pages 67–77

- Jan Gonda (1970 through 1987), A History of Indian Literature, Volumes 1 to 7, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3-447-02676-5

- Teun Goudriaan and Sanjukta Gupta (1981), Hindu Tantric and Śākta Literature, A History of Indian Literature, Volume 2, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3-447-02091-6, pages 7–14

- Andrew Nicholson (2013), Unifying Hinduism: Philosophy and Identity in Indian Intellectual History, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-14987-7, pages 2–5

- Karl Potter (1991), Presuppositions of India's Philosophies, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0779-2

- Greg Bailey (2001), Encyclopedia of Asian Philosophy (Editor: Oliver Leaman), Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-17281-3, pages 437–439

- John Cort (1993), Purana Perennis: Reciprocity and Transformation in Hindu and Jaina Texts (Editor: Wendy Doniger), State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-1382-1, pages 185–204

- Gregory Bailey (2003), The Study of Hinduism (Editor: Arvind Sharma), The University of South Carolina Press, ISBN 978-1-57003-449-7, page 139

- Ludo Rocher (1986), The Puranas, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3-447-02522-5, pages 1–5, 12–21

- Nair, Shantha N. (2008). Echoes of Ancient Indian Wisdom: The Universal Hindu Vision and Its Edifice. Hindology Books. p. 266. ISBN 978-81-223-1020-7.

- Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of Literature (1995 Edition), Article on Puranas, ISBN 0-877790426, page 915

- Cornelia Dimmitt (2015), Classical Hindu Mythology: A Reader in the Sanskrit Puranas, Temple University Press, ISBN 978-81-208-3972-4, page xii, 4

- Greg Bailey (2001), Encyclopedia of Asian Philosophy (Editor: Oliver Leaman), Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-17281-3, page 503

- Ludo Rocher (1986), The Puranas, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3-447-02522-5, pages 12–13, 134–156, 203–210

- Dominic Goodall (1996), Hindu Scriptures, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-20778-3, page xli

- Thompson, Richard L. (2007). The Cosmology of the Bhagavata Purana 'Mysteries of the Sacred Universe. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. p. 10. ISBN 978-81-208-1919-1.

- Ananda W. P. Guruge, 1991, The Society of the Ramayana, Page 180-200.

- Natalia Lidova (1994). Drama and Ritual of Early Hinduism. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 111–113. ISBN 978-81-208-1234-5.

- Farley P. Richmond, Darius L. Swann & Phillip B. Zarrilli 1993, p. 30.

- Tarla Mehta 1995, pp. xxiv, xxxi–xxxii, 17.

Bibliography

- Apte, Vaman Shivram (1965). The Practical Sanskrit Dictionary. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. ISBN 81-208-0567-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Deussen, Paul; Bedekar, V.M. (tr.); Palsule (tr.), G.B. (1997). Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 2. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1467-7.

- King, Richard; Ācārya, Gauḍapāda (1995), Early Advaita Vedānta and Buddhism: the Mahāyāna context of the Gauḍapādīya-kārikā, SUNY Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-2513-8

- Collins, Randall (2000). The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-00187-7.

- Mahadevan, T. M. P (1956), Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan (ed.), History of Philosophy Eastern and Western, George Allen & Unwin Ltd

- MacDonell, Arthur Anthony (2004). A Practical Sanskrit Dictionary. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-2000-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Olivelle, Patrick (1992). The Samnyasa Upanisads. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507045-3.

- Olivelle, Patrick (1998), Upaniṣads, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-283576-5

- Radhakrishnan, S.; Moore, C. A. (1957). A Source Book in Indian Philosophy. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-01958-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ranade, R. D. (1926), A constructive survey of Upanishadic philosophy, Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan

- Varghese, Alexander P (2008), India : History, Religion, Vision And Contribution To The World, Volume 1, Atlantic Publishers & Distributors, ISBN 978-81-269-0903-2

Further reading

- R.C. Zaehner (1992), Hindu Scriptures, Penguin Random House, ISBN 978-0-679-41078-2

- Dominic Goodall, Hindu Scriptures, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-20778-3

- Jessica Frazier (2014), The Bloomsbury Companion to Hindu studies, Bloomsbury Academic, ISBN 978-1-4725-1151-5

External links

Manuscripts collections (incomplete)

- A handlist of Sanskrit and Prakrit Hindu, Buddhist and Jain Manuscripts held by the Wellcome Library, Volume 1, Compiled by Dominik Wujastyk (Includes subjects such as historic Dictionaries, Drama, Erotics, Ethics, Logic, Poetics, Medicine, Philosophy, etc.)

- A handlist of Sanskrit and Prakrit Hindu, Buddhist and Jain Manuscripts held by the Wellcome Library, Volume 2, Compiled by Dominik Wujastyk (Includes subjects such as historic Dictionaries, Drama, Erotics, Ethics, Logic, Poetics, Medicine, Philosophy, etc.; for complete 6 set collection see ISBN 0-85484-049-4)

- Clay Sanskrit Library publishes Sanskrit literature with downloadable materials.

- The Sacred Books of the Hindus Information

Online resources:

- The British Library: Discovering Sacred Texts - Hinduism

- Sacred-Texts: Hinduism

- Sanskrit Documents Collection: Documents in ITX format of Upanishads, Stotras etc.

- GRETIL: Göttingen Register of Electronic Texts in Indian Languages, a cumulative register of the numerous download sites for electronic texts in Indian languages.