Mound Bayou, Mississippi

Mound Bayou is a city in Bolivar County, Mississippi, United States. The population was 1,533 at the 2010 census,[3] down from 2,102 in 2000. It is notable for having been founded as an independent black community in 1887 by former slaves led by Isaiah Montgomery.[4][5]

Mound Bayou, Mississippi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname(s): Jewel of the Delta | |

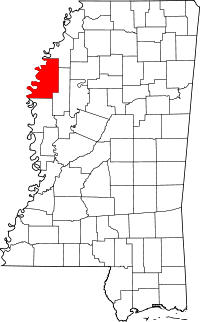

Location of Mound Bayou in Mississippi | |

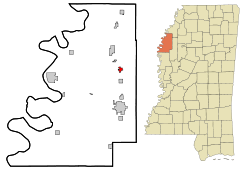

Mound Bayou, Mississippi Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 33°52′50″N 90°43′41″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Mississippi |

| County | Bolivar |

| Founded | July 12, 1887 |

| Incorporated -City status | February 23, 1898 May 12, 1972 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Eulah Peterson |

| Area | |

| • Total | 0.88 sq mi (2.27 km2) |

| • Land | 0.88 sq mi (2.27 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Elevation | 144 ft (44 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 1,533 |

| • Estimate (2019)[2] | 1,370 |

| • Density | 1,562.14/sq mi (603.39/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code | 38762 |

| Area code(s) | 662 |

| FIPS code | 28-49320 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0673895 |

| Website | www |

Mound Bayou has a 98.6 percent African-American majority population, one of the largest of any community in the United States. The current mayor of Mound Bayou is Eulah Peterson.

Geography

U.S. Routes 61 and 278 bypass Mound Bayou to the west and lead south 9 miles (14 km) to Cleveland, the largest city in Bolivar County, and north 27 miles (43 km) to Clarksdale.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city of Mound Bayou has a total area of 0.9 square miles (2.3 km2), all land.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1900 | 287 | — | |

| 1910 | 537 | 87.1% | |

| 1920 | 803 | 49.5% | |

| 1930 | 834 | 3.9% | |

| 1940 | 806 | −3.4% | |

| 1950 | 1,328 | 64.8% | |

| 1960 | 1,354 | 2.0% | |

| 1970 | 2,134 | 57.6% | |

| 1980 | 2,917 | 36.7% | |

| 1990 | 2,222 | −23.8% | |

| 2000 | 2,102 | −5.4% | |

| 2010 | 1,533 | −27.1% | |

| Est. 2019 | 1,370 | [2] | −10.6% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[6] | |||

As of the 2010 United States Census,[7] there were 1,533 people living in the city. The racial makeup of the city was 98.0% Black, 0.9% White, 0.1% Asian and 0.1% from two or more races. 0.9% were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

As of the census[8] of 2000, there were 2,102 people, 687 households, and 504 families living in the city. The population density was 2,395.1 people per square mile (922.3/km2). There were 723 housing units at an average density of 823.8 per square mile (317.2/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 98.43% African American, 0.05% Native American, 0.24% Asian, 0.81% White, 0.05% from other races, and 0.43% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.38% of the population.

There were 687 households, out of which 38.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 24.7% were married couples living together, 43.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 26.5% were non-families. 24.7% of all households were made up of individuals, and 9.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.06 and the average family size was 3.66.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 34.7% under the age of 18, 12.9% from 18 to 24, 23.5% from 25 to 44, 19.1% from 45 to 64, and 9.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 27 years. For every 100 females, there were 78.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 67.6 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $17,972, and the median income for a family was $19,770. Males had a median income of $21,700 versus $18,988 for females. The per capita income for the city was $8,227. About 41.9% of families and 45.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 58.5% of those under age 18 and 34.5% of those age 65 or over.

History

.jpg)

Mound Bayou traces its origin to freed African Americans from the community of Davis Bend, Mississippi. Davis Bend was started in the 1820s by planter Joseph E. Davis (elder brother of former Confederate president Jefferson Davis), who intended to create a model slave community on his plantation. Davis was influenced by the utopian ideas of Robert Owen. He encouraged self-leadership in the slave community, provided a higher standard of nutrition and health and dental care, and allowed slaves to become merchants. In the aftermath of the Civil War, Davis Bend became an autonomous free community when Davis sold his property to former slave Benjamin Montgomery, who had run a store and been a prominent leader at Davis Bend. The prolonged agricultural depression, falling cotton prices, flooding by the Mississippi River, and white hostility in the region contributed to the economic failure of Davis Bend.

Isaiah T. Montgomery led the founding of Mound Bayou in 1887 in wilderness in northwest Mississippi. The bottomlands of the Delta were a relatively undeveloped frontier, and blacks had a chance to make money by clearing land and use the profits to buy lands in such frontier areas. By 1900 two-thirds of the owners of land in the bottomlands were black farmers. With the loss of political power due to state disenfranchisement, high debt and continuing agricultural problems, most of them lost their land and by 1920 were landless sharecroppers. As cotton prices fell, the town suffered a severe economic decline in the 1920s and 1930s.

Shortly after a fire destroyed much of the business district, Mound Bayou began to revive in 1942 after the opening of the Taborian Hospital by the International Order of Twelve Knights and Daughters of Tabor, a fraternal organization. For more than two decades, under its Chief Grand Mentor Perry M. Smith, the hospital provided low-cost health care to thousands of blacks in the Mississippi Delta. The chief surgeon was Dr. T.R.M. Howard, who eventually became one of the wealthiest black men in the state. Howard owned a plantation of more than 1,000 acres (4.0 km2), a home-construction firm, a small zoo, and built the first swimming pool for blacks in Mississippi.

In 1952, Medgar Evers moved to Mound Bayou to sell insurance for Howard's Magnolia Mutual Life Insurance Company. Howard introduced Evers to civil rights activism through the Regional Council of Negro Leadership which organized a boycott against service stations that refused to provide restrooms for blacks. The RCNL's annual rallies in Mound Bayou between 1952 and 1955 drew crowds of ten thousand or more. During the trial of Emmett Till's killers, black reporters and witnesses stayed in Howard's Mound Bayou home, and Howard gave them an armed escort to the courthouse in Sumner.

Author Michael Premo wrote:

Mound Bayou was an oasis in turbulent times. While the rest of Mississippi was violently segregated, inside the city there were no racial codes ... At a time when blacks faced repercussions as severe as death for registering to vote, Mound Bayou residents were casting ballots in every election. The city has a proud history of credit unions, insurance companies, a hospital, five newspapers, and a variety of businesses owned, operated, and patronized by black residents. Mound Bayou is a crowning achievement in the struggle for self-determination and economic empowerment.[9]

Education

From its earliest years, Mound Bayou has struggled with inadequate educational infrastructure. According to a 1915 report in the Cincinnati Labor Advocate, Mound Bayou's school was attended by more than 300 students who were forced to make use of equipment held to be "inadequate for 50 pupils."[10] Teachers at the school were "poorly paid" and the school year limited to only five months.[10]

Today the city of Mound Bayou is served by the North Bolivar Consolidated School District, which operates I.T. Montgomery Elementary School and John F. Kennedy Memorial High School in Mound Bayou.

On July 1, 2014, the North Bolivar School District consolidated with the Mound Bayou Public School District to form the North Bolivar Consolidated School District.[11]

Cultural references

The 8-minute 1994 film Letters from Mound Bayou, directed by Betsy Cox, which opened the first afternoon session of screenings at the 2006 Langston Hughes African American Film Festival, depicted the return of midwife sister Mary Stella Simpson to Mound Bayou.[12][13] Mound Bayou's legacy in blues and rhythm & blues extends from the earliest Delta blues to 21st century southern soul.[14] [15] Ed Townsend wrote the Marvin Gaye hit song "Let's Get It On" in Mound Bayou. [16]

Notable people

Born in Mound Bayou:

- Mary Booze, first African-American woman to sit on the Republican National Committee, 1924 to her death in 1948; born in Mound Bayou in 1877

- General Crook, musician

- Lorenzo Gray, baseball player

- Katie Hall, U.S. Representative from Indiana from 1982 to 1985

- Michael Harris, professor and Associate Dean of Engineering for Undergraduate Education and Engagement at Purdue University.[17]

- Kevin Henry, football player

- Russell Holmes, Massachusetts state representative (6th Suffolk)

- Melvin "Mel" Reynolds, disgraced politician

- Kelly Miller Smith, Sr., preacher, author, and civil rights leader

Lived or worked in Mound Bayou:

- Isaiah Montgomery, town founder

- Medgar Evers, civil rights leader

- Myrlie Evers-Williams, widow of Medgar Evers; civil rights leader, journalist, NAACP Chair; delivered invocation at Barack Obama's second inauguration

- Fannie Lou Hamer, civil rights leader

- T.R.M. Howard, leader of civil rights and fraternal organizations, entrepreneur and surgeon

- Harold Robert Perry, first African-American to serve as a Catholic bishop in the 20th century; former pastor at St. Gabriel's Church in Mound Bayou

- Lewis Ossie Swingler, journalist, editor, and newspaper publisher

- Ed Townsend, singer, songwriter, producer, and attorney

- Minnie Fisher, local community activist

Sources

- Hermann, Janet (1981). The Pursuit of a Dream. New York: OUP.

- Beito, David and Linda (2009). Black Maverick: T.R.M. Howard's Fight for Civil Rights and Economic Power. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-03420-6.

References

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Mound Bayou city, Mississippi". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved January 21, 2014.

- Wormser, Richard (October 18, 2002). "Isiah Washington". Jim Crow Stories: The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow. Educational Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on October 18, 2002. Retrieved October 18, 2002.

- Educational Broadcasting Corporation (December 28, 2002). "Williams v. Mississippi (1898)". Jim Crow Stories: The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow. Public Broadcasting Service. Archived from the original on December 28, 2002. Retrieved April 5, 2003.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2016-10-14.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- Premo, Michael (November 10, 2007). "Mound Bayou, Mississippi – The Jewel of the Delta". storycorps.org. Archived from the original on April 15, 2013.

- "Hustling Town of Negroes Only Built in Mississippi," Labor Advocate [Cincinnati, OH], July 17, 1915, pg. 2.

- "School District Consolidation in Mississippi Archived 2017-07-02 at the Wayback Machine." Mississippi Professional Educators. December 2016. Retrieved on July 2, 2017. Page 2 (PDF p. 3/6).

- "LHAAFF Program.indd" (PDF). Langstonarts.org. Retrieved 2017-05-02.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-09-05. Retrieved 2014-09-04.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Mound Bayou Blues". Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- "Mound Bayou Blues historical marker". Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- J. M. Martin (15 August 2016). "Natural Resources". Oxford American, Issue 93, Summer 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- "A Distinguished Role Model" (PDF). The Future is Now. University of Tennessee. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 June 2010. Retrieved 3 January 2016.