Igorot people

The Igorot (Tagalog for 'mountaineer') are any of various ethnic groups in the mountains of northern Luzon, Philippines, all of whom keep, or have kept until recently, their traditional religion and way of life. Some live in the tropical forests of the foothills, but most live in rugged grassland and pine forest zones higher up. The Igorot numbered about 1.5 million in the early 21st century. Their languages belong to the northern Luzon subgroup of the Philippine languages, which belong to the Austronesian (Malayo-Polynesian) family.

A group of elderly Igorots. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 1,500,000[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

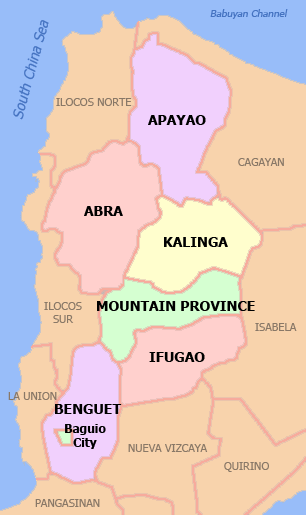

(Cordillera Administrative Region, Ilocos Region, Cagayan Valley) | |

| Languages | |

| Bontoc, Ilocano, Itneg, Ibaloi, Isnag, Kankanaey, Kalanguya, Filipino, English | |

| Religion | |

| Paganism, Animism, Christianity (Roman Catholicism, Episcopalianism, other Protestant sects) |

Etymology

From the root word golot, which means "mountain", Igolot means "people from the mountains" (Tagalog: “Mountaineer”), a reference to any of various ethnic groups in the mountains of northern Luzon. Their languages belong to the northern Luzon subgroup of the Philippine languages, which belong to the Austronesian (Malayo-Polynesian) family.

The endonyms Ifugao or Ipugaw (also meaning "mountain people") are used more frequently by the Igorots themselves, as igorot is viewed by some as slightly pejorative,[2] except by the Ibaloys.[3]

Cordillera ethnic groups

The Igorots may be roughly divided into two general subgroups: the larger group lives in the south, central and western areas, and is very adept at rice-terrace farming; the smaller group lives in the east and north. Prior to Spanish colonisation of the islands, the peoples now included under the term did not consider themselves as belonging to a single, cohesive ethnic group.[2]

They may be further subdivided into five ethnolinguistic groups: the Bontoc, Ibaloi, Isnag (or Isneg/Apayao), Kalinga, and the Kankanaey.[4]

Bontoc

_(14579727919).jpg)

The Bontoc live on the banks of the Chico River in the Central Mountain Province on the island of Luzon. They speak Bontoc and Ilocano. They formerly practiced head-hunting and had distinctive body tattoos. The Bontoc describe three types of tattoos: The chak-lag′, the tattooed chest of the head taker; pong′-o, the tattooed arms of men and women; and fa′-tĕk, for all other tattoos of both sexes. Women were tattooed on the arms only.

In the past, the Bontoc engaged in none of the usual pastimes or games of chance practiced in other areas of the country, but did perform a circular rhythmic dance acting out certain aspects of the hunt, always accompanied by the gang′-sa or bronze gong. There was no singing or talking during the dance drama, but the women took part, usually outside the circumference. It was a serious but pleasurable event for all concerned, including the children.[5] Present-day Bontocs are a peaceful agricultural people who have, by choice, retained most of their traditional culture despite frequent contacts with other groups.

The pre-Christian Bontoc belief system centers on a hierarchy of spirits, the highest being a supreme deity called Intutungcho, whose son, Lumawig, descended from the sky (chayya), to marry a Bontoc girl. Lumawig taught the Bontoc their arts and skills, including irrigation of their land. The Bontoc also believe in the anito, spirits of the dead, who are omnipresent and must be constantly consoled. Anyone can invoke the anito, but a seer (insup-ok) intercedes when someone is sick through evil spirits.[6]

_(14579912297).jpg)

The Bontoc social structure used to be centered around village wards (ato) containing about 14 to 50 homes. Traditionally, young men and women lived in dormitories and ate meals with their families. This gradually changed with the advent of Christianity. In general, however, it can be said that all Bontocs are very aware of their own way of life and are not overly eager to change.

Ibaloi

The Ibaloi (also Ibaloi, Ibaluy, Nabaloi, Inavidoy, Inibaloi, Ivadoy) and Kalanguya (also Kallahan and Ikalahan) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Philippines who live mostly in the southern part of Benguet, located in the Cordillera of northern Luzon, and Nueva Vizcaya in the Cagayan Valley region. They were traditionally an agrarian society. Many of the Ibaloi and Kalanguya people continue with their agriculture and rice cultivation.

Their native language belongs to the Malayo-Polynesian branch of the Austronesian languages family and is closely related to the Pangasinan language, primarily spoken in the province of Pangasinan, located southwest of Benguet.

Baguio, the major city of the Cordillera, dubbed the "Summer Capital of the Philippines," is located in southern Benguet.

The largest feast of the Ibaloi is the Pesshet, a public feast mainly sponsored by people of prestige and wealth. Pesshet can last for weeks and involves the killing and sacrifice of dozens of animals.

One of the more popular dances of the Ibaloi is the bendiyan, a mass dance participated in by hundreds of male and female dancers. Originally a victory dance in time of war, it evolved into a celebratory dance. It is used as entertainment (ad-adivay) in the cañao feasts, hosted by the wealthy class (baknang).[7]

Ifugao

Ifugaos are the people inhabiting Ifugao Province. They come from the municipalities of Lagawe (Capital Town), Aguinaldo, Alfonso Lista, Asipulo, Banaue, Hingyon, Hungduan, Kiangan, Lamut, Mayoyao and Tinoc.

The term "Ifugao" is derived from "ipugo" which means "earth people", "mortals" or "humans", as distinguished from spirits and deities. It also means "from the hill", as pugo means hill.[8] The province of Ifugao in the southeastern part of the Cordillera region is best known for its famous Banaue Rice Terraces, which in modern times have become one of the major tourist attractions of the Philippines and one of the eight wonders of the world.

Traditionally, Ifugaos build their typical houses (bale), consisting of one room, built on 4 wooden posts 3 meters off the ground. There is a detachable ladder (tete) for the front door (panto). Huts are temporary buildings. Rice granaries are called alang, protected by a wooden idol (bulul).[8]

Aside from their rice terraces, the Ifugaos, who speak four distinct dialects, are known for their rich oral literary traditions of hudhud and the alim. Due to being isolated by the terrain, Ifugaos usually speak in English and Ilocano as their alternative to their mother tongue. Most Ifugaos are fluent in Filipino/Tagalog.

The Ifugaos’ highest prestige feasts are the hagabi, sponsored by the elite (kadangyan); and the uyauy, a marriage feast sponsored by those immediately below the wealthiest (inmuy-ya-uy). The middle class are the tagu, while the poor are the nawotwot.[8]

Alim and Hudhud Oral traditions of Ifugao of Ifugao people of the Cordillera Administrative Region in Luzon island of Philippines. In 2001, the Hudhud Chants of the Ifugao was chosen as one of the 11 Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity. It was then formally inscribed as a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2008.

Isneg

The Isnag, also Isneg or Apayao, live at the northwesterly end of northern Luzon, in the upper half of the Cordillera province of Apayao. The term "Isneg" derives from itneg, meaning inhabitants of the Tineg River. Apayao derives from the battle cry Ma-ap-ay-ao as their hand is clapped rapidly over their mouth. They may also refer to themselves as Imandaya if they live upstream, or Imallod if they live downstream. The municipalities in the Isneg domain include Pudtol, Kabugao, Calanasan, Flora, Conner, Sta. Marcela, and Luna. Two major river systems, the Abulog River and the Apayao River, run through Isnag country.[9]

Jars of basi are half buried in the ground within a small shed, abulor, constructed of 4 posts and a shed. This abulor is found within the open space, linong or sidong, below their houses (balay). They grow upland rice, while also practicing swidden farming, and fishing.[9]:99–100,102

Say-am was an important ceremony after a successful headhunting, or other important occasions, hosted by the wealthy, and lasting one to five days or more. Dancing, singing, eating and drinking mark the feast, and Isnegs wear their finest clothes. The shaman, Anituwan, prays to the spirit Gatan, before the first dog is sacrificed, if a human head had not been taken, and offered at the sacred tree, ammadingan. On the last day, a coconut is split in honor of the headhunter guardian, Anglabbang.The Pildap is an equivalent say-am but hosted by the poor. Conversion to Christianity grew after 1920, and today, the Isnegs are divided in their religious beliefs, with some still being animistic.[9]:107–108,110–111,113

Kalinga

The Kalinga, also known as "iKalingas", inhabit the drainage basin of the middle Chico River in Kalinga Province. The Kalinga are sub-divided into Southern and Northern groups; the latter is considered the most heavily ornamented people of the northern Philippines.

The Kalinga practice both wet and dry rice farming. They also developed an institution of peace pacts called Bodong which has minimised traditional warfare and headhunting and serves as a mechanism for the initiation, maintenance, renewal and reinforcement of kinship and social ties.[10]

They also speak different kalinga tribal languages, Ilocano, Tagalog and English Kalinga, Ilocano languages. Kalinga society is very kinship-oriented, and relatives are held responsible for avenging any injury done to a member. Disputes are usually settled by the regional leaders, who listen to all sides and then impose fines on the guilty party. These are not formal council meetings, but carry a good deal of authority.

Kankanaey

.jpg)

The Kankanaey domain includes Western Mountain Province, northern Benguet and southeastern Ilocos Sur. Like most Igorot ethnic groups, the Kankanaey built sloping terraces to maximize farm space in the rugged terrain of the Cordilleras.

Kankanaey houses include the two-story innagamang, the larger binangi, the cheaper tinokbob, and the elevated tinabla. Their granaries (agamang) are elevated to avoid rats. Two other institutions of the Kankanaey of Mountain Province are the dap-ay, or the men's dormitory and civic center, and the ebgan, or the girls' dormitory.[11][12]

Kankanaey's major dances include tayaw, pat-tong, takik (a wedding dance), and balangbang. The tayaw is a community dance that is usually done in weddings it maybe also danced by the Ibaloi but has a different style. Pattong, also a community dance from Mountain Province which every municipality has its own style, while Balangbang is the dance's modern term. There are also some other dances like the sakkuting, pinanyuan (another wedding dance) and bogi-bogi (courtship dance).

"Hard" and "Soft" Kankanaey

The name Kankanaey came from the language which they speak. The only difference amongst the Kankanaey are the way they speak such as intonation and word usage.

In intonation, there is distinction between those who speak Hard Kankanaey (Applai) and Soft Kankanaey. Speakers of Hard Kankanaey are from the towns of Sagada and Besao in the western Mountain Province as well as their environs. They speak Kankanaey with a hard intonation where they differ in some words from the soft-speaking Kankanaey.

Soft-speaking Kankanaey come from Northern and other parts of Benguet, and from the municipalities of Sabangan, Tadian and Bauko in Mountain Province. In words for example an Applai might say otik or beteg (pig) and the soft-speaking Kankanaey use busaang or beteg as well. The Kankanaey may also differ in some words like egay or aga, maid or maga. They also differ in their ways of life and sometimes in culture.

The Kankanaey are also internally identified by the language they speak and the province from whence they came. Kankanaey people from Mountain Province may call the Kankanaey from Benguet as iBenget while the Kankanaey of Benguet may call their fellow Kankanaey from Mountain Province iBontok.

The Hard and Soft Kankanaey also differ in the way they dress. Women's dress of the Soft dialect generally has a colour combination of black, white and red. The design of the upper attire is a criss-crossed style of black, white and red colors. The skirt or tapis is a combination of stripes of black, white and red.

Hard dialect women dress in mainly red and black with less white, with the skirt or tapis which is mostly called bakget and gateng. The men formerly wore a g-string known as a wanes for the Kanakaney's of Besao and Sagada. The design of the wanes may vary according to social status or municipality.

Ethnic groups by linguistic classification

Below is a list of northern Luzon ethnic groups organized by linguistic classification.

- Northern Luzon languages

- Ilokano (Ilocos Norte and Ilocos Sur)

- Northern Cordilleran

- Central Cordilleran

- Kalinga–Itneg

- Kalinga (Kalinga Province)

- Itneg (Abra Province)

- Nuclear

- Ifugao (Ifugao Province)

- Balangao (eastern Mountain Province)

- Bontok (central Mountain Province)

- Kankanaey (western Mountain Province, northern Benguet Province)

- Kalinga–Itneg

- Southern Cordilleran

- Ibaloi (southern Benguet Province)

- Kalanguya/Kallahan (eastern Benguet Province, Ifugao Province, northwestern Nueva Vizcaya Province)[13]

- Karao (Karao, Bokod, Benguet)

- Ilongot (eastern Nueva Vizcaya Province, western Quirino Province)

- Pangasinan (Pangasinan Province)

History

The gold found in the land of the Igorot were an attraction for the Spanish.[17] Originally gold was exchanged at Pangasinan by the Igorot.[18] The gold was used to buy consumable products by the Igorot.[19] Both gold and desire to Christianize the Igorot were given as reasons for Spanish conquest.[20] In 1572 the Spanish started hunting for the gold.[21] Benguet Province was entered by the Spanish with the intention of obtaining gold.[22] The fact that the Igorots managed to stay out of Spanish dominion vexed the Spaniards.[23] The gold evaded the hands of the Spaniards due to Igorot opposition.[24]

Samuel E. Kane wrote about his life amongst the Bontoc, Ifugao, and Kalinga after the Philippine–American War, in his book Thirty Years with the Philippine Head-Hunters (1933).[25] The first American school for Igorot girls was opened in Baguio in 1901 by Alice McKay Kelly.[25]:317 Kane noted that Dean C. Worcester "did more than any one man to stop head-hunting and to bring the traditional enemy tribes together in friendship."[25]:329 Kane wrote of the Igorot people, "there is a peace, a rhythm and an elemental strength in the life...which all the comforts and refinements of civilization can not replace...fifty years hence...there will be little left to remind the young Igorots of the days when the drums and ganzas of the head-hunting canyaos resounded throughout the land.[25]:330–331

In 1904, a group of Igorot people were brought to St. Louis, Missouri, United States for the St. Louis World's Fair. They constructed the Igorot Village in the Philippine Exposition section of the fair, which became one of the most popular exhibits. The poet T. S. Eliot, who was born and raised in St. Louis, visited and explored the Village. Inspired by their tribal dance and others, he wrote the short story, "The Man Who Was King" (1905).[26] In 1905, 50 tribespeople were on display at a Brooklyn, New York amusement park for the summer, ending in the custody of the unscrupulous Truman K. Hunt, a showman "on the run across America with the tribe in tow."[27]

During the Japanese occupation of the Philippines, Igorots fought against Japan. Donald Blackburn's World War II guerrilla force had a strong core of Igorots.[28]:148–165

In 2014, Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, an indigenous rights advocate, of Igorot ethnicity, was appointed UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.[29]

See also

- Ethnicities of the Philippine Cordilleras

- Demographics of the Philippines

- Ethnic groups in the Philippines

- Indigenous peoples of the Philippines

- Proto-Malay

- Gaddang people

- Ibanag people

- Tagalog people

- Kapampangan people

- Ilocano people

- Ivatan people

- Pangasinan people

- Bicolano people

- Negrito

- Visayan people

- Lumad

- Moro people

References

- Editors, The (2015-03-26). "Igorot | people". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2015-09-03.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Carol R. Ember; Melvin Ember (2003). Encyclopedia of sex and gender: men and women in the world's cultures, Volume 1. Springer. p. 498. ISBN 978-0-306-47770-6.

- Communication, UP College of Mass. "Ibaloys "Reclaiming" Baguio: The Role of Intellectuals". Plaridel Journal.

- "IGOROT Ethnic Groups - sagada-igorot.com".

- "The Bontoc Igorot".

- Sumeg-ang, Arsenio (2005). "1 The Bontoks". Ethnography of the Major Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Cordillera. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. pp. 1–27. ISBN 9789711011093.

- Sumeg-ang, Arsenio (2005). "2 The Ibaloys". Ethnography of the Major Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Cordillera. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. pp. 28–51. ISBN 9789711011093.

- Sumeg-ang, Arsenio (2005). "4 The Ifugaos". Ethnography of the Major Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Cordillera. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. pp. 71–91. ISBN 9789711011093.

- Sumeg-ang, Arsenio (2005). "5 The Isnegs". Ethnography of the Major Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Cordillera. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. pp. 92–93. ISBN 9789711011093.

- Sumeg-ang, Arsenio (2005). "5 The Kalingas". Ethnography of the Major Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Cordillera. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. pp. 115–135. ISBN 9789711011093.

- Sumeg-ang, Arsenio (2005). "7 The Northern Kankana-eys". Ethnography of the Major Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Cordillera. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. p. 143. ISBN 9789711011093.

- Sumeg-ang, Arsenio (2005). "8 The Southern Kankana-eys". Ethnography of the Major Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Cordillera. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. pp. 161–162. ISBN 9789711011093.

- "Kalanguya Archives - Intercontinental Cry".

- "Kallahan, Keley-i".

- "Kalanguya".

- Project, Joshua. "Kalanguya, Tinoc in Philippines".

- Barbara A. West (19 May 2010). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase Publishing. pp. 300–. ISBN 978-1-4381-1913-7.

- "Ifugao - Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life - Encyclopedia.com".

- Linda A. Newson (2009). Conquest and Pestilence in the Early Spanish Philippines. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 232–. ISBN 978-0-8248-3272-8.

- "Benguet mines, forever in resistance by the Igorots – Amianan Balita Ngayon".

- "Ethnic History (Cordillera) - National Commission for Culture and the Arts". ncca.gov.ph.

- Melanie Wiber (1993). Politics, Property and Law in the Philippine Uplands. Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press. pp. 27–. ISBN 978-0-88920-222-1.

igorot gold spanish.

- "The Igorot struggle for independence: William Henry Scott".

- Habana, Olivia M. (1 January 2000). "Gold Mining in Benguet to 1898". Philippine Studies. 48 (4): 455–487. JSTOR 42634423.

- Kane, S.E., 1933, Life and Death in Luzon or Thirty Years with the Philippine Head-Hunters, New York: Grosset & Dunlap

- Narita, Tatsushi. "How Far is T. S. Eliot from Here?: The Young Poet's Imagined World of Polynesian Matahiva," In How Far is America from Here?, ed. Theo D'haen, Paul Giles, Djelal Kadir and Lois Parkinson Zamora. Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi, 2005, pp .271-282.

- Prentice, Claire, 2014, The Lost Tribe of Coney Island: Headhunters, Luna Park, and the Man Who Pulled Off the Spectacle of the Century, New Harvest. "The Lost Tribe of Coney Island: Product Details". Amazon.com. October 14, 2014. Retrieved November 13, 2014.

- Harkins, P., 1956, Blackburn's Headhunters, London: Cassell & Co. LTD

- James Anaya Victoria Tauli-Corpuz begins as new Special Rapporteur, 02 June 2014

Further reading

- Boeger, Astrid. 'St. Louis 1904'. In Encyclopedia of World's Fairs and Expositions, ed. John E. Findling and Kimberly D. Pelle. McFarland, 2008.

- Conklin, Harold C., Pugguwon Lupaih, Miklos Pinther, and the American Geographical Society of New York. (1980). American Geographical Society of New York (ed.). Ethnographic Atlas of Ifugao: A Study of Environment, Culture, and Society in Northern Luzon. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-02529-7.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Jones, Arun W, “A View from the Mountains: Episcopal Missionary Depictions of the Igorot of Northern Luzon, The Philippines, 1903-1916” in Anglican and Episcopal History 71.3 (Sep 2002): 380-410.

- Narita, Tatsushi."How Far is T. S. Eliot from Here?: The Young Poet's Imagined World of Polynesian Matahiva". In How Far is America from Here?, ed. Theo D'haen, Paul Giles, Djelal Kadir and Lois Parkinson Zamora. Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi, 2005, pp. 271–282.

- Narita, Tatsushi. T. S. Eliot, the World Fair of St. Louis and 'Autonomy' (Published for Nagoya Comparative Culture Forum). Nagoya: Kougaku Shuppan Press, 2013.

- Rydell, Robert W. All the World's a Fair: Visions of Empire at American International Expositions, 1876–1916. The University of Chicago Press, 1984.

- Cornélis De Witt Willcox (1912). The head hunters of northern Luzon: from Ifugao to Kalinga, a ride through the mountains of northern Luzon : with an appendix on the independence of the Philippines. Volume 31 of Philippine culture series. Franklin Hudson Publishing Co. Retrieved 24 April 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Igorot. |