Tausūg people

The Tausūg or Suluk (Tausug: Tau Sūg) are an ethnic group of the Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia. The Tausūg are part of the wider political identity of Muslims of Mindanao, Sulu and Palawan. Most of the Tausugs have converted into the religion of Islam whose members are now more known as the Moro group, who constitute the third largest ethnic group of Mindanao, Sulu and Palawan. The Tausugs originally had an independent state known as the Sulu Sultanate, which once exercised sovereignty over the present day provinces of Basilan, Palawan, Sulu, Tawi-Tawi, Zamboanga City, the eastern part of the Malaysian state of Sabah (formerly North Borneo) and North Kalimantan in Indonesia.

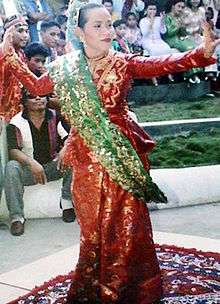

Tausug woman in a pangalay dance. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 1.5 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

(Bangsamoro, Davao Region, Northern Mindanao, Zamboanga Peninsula, Palawan, Manila, Cebu) (North-eastern part of Sabah, Kuala Lumpur, Johor) (North Kalimantan) | |

| Languages | |

| Tausūg, Zamboangueño Chavacano, Cebuano, Filipino, English, Malay, Indonesian | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Sunni Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Visayans, Moros, other Filipinos, Malays, and other Austronesian peoples |

Etymology

"Tausug" (Tausug: Tau Sūg) means "the people of the current", from the word tau which means "man" or "people" and sūg (alternatively spelled sulug or suluk) which means "[sea] currents".[2] The term Tausūg was derived from two words tau and sūg (or suluk in Malay) meaning "people of the current", referring to their homelands in the Sulu Archipelago. Sūg and suluk both mean the same thing, with the former being the phonetic evolution in Sulu of the latter (the L being dropped and thus the two short U's merging into one long U). The Tausūg in Sabah refer to themselves as Tausūg but refers to their ethnic group as "Suluk" as documented in official documents such as birth certificates in Sabah, which are written Malay.

History

Pre-Islamic era

Prior to the establishment of the sultanate, the Tausug lived in communities called a banwa. Each banwa is headed by a leader known as a panglima along with a shaman called a mangungubat. The panglima is usually a man with a strong political and physical leadership among the community folks. The shaman may either be a man or a woman, and they are specialized in contacting the spiritual realm. The shamans are also exempted from practicing traditional marriage as they can have sensual relationships with the same sex, a common trait in numerous tribes throughout the Philippine archipelago and northern Borneo in pre-Islamic and pre-Christian times. Each banwa is considered as an independent state, the same with the city-states of other regions in Asia. The Tausug during the era had trade relations with other neighboring Tausug banwas, the Yakan of Basilan, and the nomadic Sama Bajau.

Scott (1994) mentions the origins of the Tausugs as being the descendants of ancient Butuanons and Surigaonons from the Rajahnate of Butuan, who established a Spice trading port in pre-Islamic Sulu. Sultan Batara Shah Tengah, who ruled as Sultan in 1600, was said to be an actual native of Butuan.[4] The Butuanon-Surigaonon origins of the Tausugs suggests the relationship of their languages and they had been recently grouped under the Southern sub-family of Visayan.[5]

Sultanate era

.jpg)

The history of Sulu begins with Karim-ul Makhdum, a Muslim missionary, who arrived in Sulu in 1380. He introduced the Islamic faith and settled in Tubig Indangan, Simunul, until his death. The Mosque's pillars at Tubig-Indangan, which he built, still stand. In 1390, Rajah Baguinda Ali landed at Buansa, and extended the missionary work of Makhdum. The Johore-born Arab adventurer Sayyid Abubakar Abirin arrived in 1450, married Baguinda's daughter, Dayang-dayang Paramisuli. After Rajah Baguinda's death, Sayyid Abubakar became Sultan, thereby introducing the sultanate as a political system (the Sultanate of Sulu). Political districts were created in Parang, Pansul, Lati, Gitung, and Luuk, each headed by a panglima or district leader. After Sayyid Abubakar's death, the sultanate system had already become well established in Sulu. Before the coming of the Spaniards, the ethnic groups in Sulu — the Tausug, Samal, Yakan, and Bajau - were in varying degrees united under the Sulu sultanate, considered the most centralised political system in the Philippines. Called the "Spanish–Moro conflict", these battles were waged intermittently from 1578 till 1898, between the Spanish colonial government and the Bangsamoro people of Mindanao and Sulu.

.png)

In 1578, an expedition sent by Gov Francisco de Sande and headed by Capt. Rodriguez de Figueroa began the 300-year warfare between the Moro Tausūg and the Spanish authorities. In 1579, the Spanish government gave de Figueroa the sole right to colonise Mindanao. In retaliation, the Moro raided Visayan towns in Panay, Negros, and Cebu for they know the Spanish will get foot soldiers in this areas. These were repulsed by Spanish and Visayan forces. In the early 17th century, the largest alliance composed of the Maranao, Maguindanao, Tausūg, and other Moro and Lumad groups, was formed by Sultan Kudarat or Cachil Corralat of Maguindanao, whose domain extended from the Davao Gulf to Dapitan on the Zamboanga peninsula. Several expeditions sent by the Spanish authorities suffered defeat. In 1635, Capt Juan de Chaves occupied Zamboanga and erected a fort. In 1637, Gov Gen Hurtado de Corcuera personally led an expedition against Kudarat, and temporarily triumphed over his forces at Lamitan and Iliana Bay. On 1 January 1638, de Corcuera, with 80 vessels and 2000 soldiers, defeated the Moro Tausūg and occupied Jolo mainly staying inside captured Cottas. A peace treaty was forged. The victory did not establish Spanish sovereignty over Sulu, as the Tausūg abrogated the treaty as soon as the Spaniards left in 1646.[6] But later Sultanate of Sulu totally gave up its rule over south Palawan to Spain in 1705 and over Basilan in 1762. In the last quarter of the 19th century Moros in the Sultanate of Sulu formally recognised Spanish sovereignty, but these areas remained partially controlled by the Spanish as their sovereignty was limited to military stations and garrisons and pockets of civilian settlements in Zamboanga and Cotabato (the latter is under Sultanate of Maguindanao), until they had to abandon the region as a consequence of their defeat in the Spanish–American War.

In 1737, Sultan Alimud Din I for personal interest, entered into a "permanent" peace treaty with Gov Gen F. Valdes y Tamon; and in 1746, befriended the Jesuits sent to Jolo by King Philip. The "permission" of Sultan Azimuddin-I (*the first heir-apparent) allowed the Catholic Jesuits to enter Jolo, but was argued against by his young brother, Raja Muda Maharajah Adinda Datu Bantilan (*the second heir-apparent). Datu Bantilan did not want the Catholic Jesuits to disturb or dishonor the Moro faith in the Sulu Sultanate kingdom. The brothers then fought, causing Sultan Azimuddin-I to leave Jolo and head to Zamboanga, then to Manila in 1748. Then, Raja Muda Maharajah Adinda Datu Bantilan was proclaimed as Sultan, taking the name as Sultan Bantilan Muizzuddin.

In 1893, amid succession controversies, Amir ul Kiram became Sultan Jamalul Kiram II, the title being officially recognised by the Spanish authorities. In 1899, after the defeat of Spain in the Spanish–American War, Col. Luis Huerta, the last governor of Sulu, relinquished his garrison to the Americans. (Orosa 1970:25-30). Prior to modern times, the Tausūg were under the Sultanate of Sulu. The system is a patrilineal system, consisting of the title of Sultan as the sole sovereign of the Sultanate (in Tausūg language: Lupah Sug, literally: "Land of the Current"), followed by various Maharajah and Rajah-titled subdivisional princes. Further down the line are the numerous Panglima or local chiefs, similar in function to the modern Philippine political post of the Baranggay Kapitan in the Baranggay system. Of significance are the Sarip (Sharif) and their wives, Sharifah, who are Hashemite descendants of the Islamic prophet, Muhammad. They are respected as religious leaders, though some may take up administrative posts.

In the northern area of Borneo in Sabah, most of the recognised citizens have lived in the area since the rule of the Sultanate of Sulu.[7][note 1] During the British administration of North Borneo, a recognised Bajau-Suluk warrior in the Malaysian history help to fight off the British in a battle known as Mat Salleh Rebellion and gained many supports from other natives. During the Second World War when the Japanese occupied the northern Borneo area, the native Suluks once again engaged in a struggle to fight off the Japanese where many of them including women and children were massacred after their revolt with the Chinese was foiled by the Japanese.

Modern era

Philippines

A "policy of attraction" was introduced, ushering in reforms to encourage Muslim integration into Philippine society. "Proxy colonialism" was legalised by the Public Land Act of 1919, invalidating Tausūg pusaka (inherited property) laws based on the Islamic Shariah. The act also granted the state the right to confer land ownership. It was thought that the Muslims would "learn" from the "more advanced" Christian Filipinos, and would integrate more easily into mainstream Philippine society. In February 1920, the Philippine Senate and House of Representatives passed Act No 2878, which abolished the Department of Mindanao and Sulu, and transferred its responsibilities to the Bureau of Non-Christian Tribes under the Department of the Interior. Muslim dissatisfaction grew as power shifted to the Christian Filipinos. Petitions were sent by Muslim leaders between 1921 and 1924, requesting that Mindanao and Sulu be administered directly by the United States. These petitions were not granted. Realising the futility of armed resistance, some Muslims sought to make the best of the situation. In 1934, Arolas Tulawi of Sulu, Datu Manandang Piang and Datu Blah Sinsuat of Cotabato, and Sultan Alaoya Alonto of Lanao were elected to the 1935 Constitutional Convention. In 1935, two Muslims were elected to the National Assembly.

The Tausūg in Sulu fought against the Japanese occupation of Mindanao and Sulu during World War II and eventually drove them out. The Commonwealth sought to end the privileges the Muslims had been enjoying under the earlier American administration. Muslim exemptions from some national laws, as expressed in the administrative code for Mindanao, and the Muslim right to use their traditional Islamic courts, as expressed in the Moro Board, were ended. It was unlikely that the Muslims, who have had a longer cultural history as Muslims than the Filipinos as Christians, would surrender their identity. This incident contributed to the rise of various separatist movements - the Muslim Independence Movement (MIM), Ansar El-Islam, and Union of Islamic Forces and Organizations (Che Man 1990:74-75). In 1969, the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) was founded on the concept of a Bangsa Moro Republic by a group of educated young Muslims. In 1976, negotiations between the Philippine government and the MNLF in Tripoli resulted in the Tripoli Agreement, which provided for an autonomous region in Mindanao. Nur Misuari was invited to chair the provisional government, but he refused. The referendum was boycotted by the Muslims themselves. The talks collapsed, and fighting continued. On 1 August 1989, Republic Act 673 or the Organic Act for Mindanao, created the Autonomous Region of Mindanao, which encompasses Maguindanao, Lanao del Sur, Sulu, and Tawi-Tawi.

Malaysia

Most of the Tausūgs in Malaysia have lived since the rule of the Sultanate of Sulu in parts of Sabah with some of them actually descendants of a Sulu princess (Dayang Dayang) who had escaped from the Sulu Sultan in the 1850s when the Sultan tried to take the princess as a wife although the Sultan already have many concubines.[8] To differentiate themselves from the newly arrived Tausūg immigrants from the Philippines, most of them prefer to be called "Suluk".[9]

However, more recent Tausūg immigrants and refugees dating back to the 1970s Moro insurgency (the majority of them illegal immigrants) often face discrimination in Sabah. After the 2013 Lahad Datu standoff, there were reports of abuses by Malaysian authorities specifically on ethnic Tausūg during crackdowns in Sandakan, even on Tausūg migrants with valid papers.[10][11] Approximately nine thousand Filipino Tausūg were deported from January to November 2013.[12][13][14]

Demographics

The Tausūg number 1,226,601 in the Philippines in 2010.[15] They populate the Filipino province of Sulu as a majority, and the provinces of Zamboanga del Sur, Basilan, Tawi-Tawi, Palawan, Cebu and Manila as minorities. Many Filipino-Tausūgs have found work in neighbouring Sabah, Malaysia as construction labourers in search of better lives. However, many of them violate the law by overstaying illegally and are sometimes involved in criminal activities.[9] The Filipino-Tausūgs are not recognised as a native to Sabah.[note 1][16]

The native Tausūgs who have lived since the Sulu Sultanate era in Sabah have settled in much of the eastern parts, from Kudat town in the north, to Tawau in the south east.[7] They number around 300,000 and many of them have intermarried with other ethnic groups in Sabah, especially the Bajaus. Most prefer to use the Malay-language ethnonym Suluk in their birth certificates rather than the native Tausūg to distinguish themselves from their newly arrived Filipino relatives in Sabah. Migration fueled mainly from Sabah also created a substantial Suluk community in Greater Kuala Lumpur. While in Indonesia, most of the communities mainly settled in the northern area of North Kalimantan like Nunukan and Tarakan, which lies close to their traditional realm. There are around 12,000 (1981 estimate) Tausūg in Indonesia.[17]

Religion

The overwhelming majority of Tausūgs follow Islam, as Islam has been a defining aspect of native Sulu culture ever since Islam spread to the southern Philippines. They follow the traditional Sunni Shafi'i section of Islam, however they retain pre-Islamic religious practices and often practice a mix of Islam and Animism in their adat. A Christian minority exists. During the Spanish occupation, the presence of Jesuit missionaries in the Sulu Archipelago allowed for the conversion of entire families and even tribes and clans of Tausūgs, and other Sulu natives to Roman Catholicism. For example, Azim ud-Din I of Sulu, the 19th sultan of Sulu was converted to Roman Catholicism and baptised as Don Fernando de Alimuddin, however he reverted to Islam in his later life near death.

Some of the assimilated Filipino celebrities and politicians of Tausūg descent also tend to follow the Christian religion of the majority instead of the religion of their ancestors. For example, Maria Lourdes Sereno, the 24th Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the Philippines is of patrilineal Tausūg descent is a born-again Christian. Singer Sitti is of Tausūg and Samal descent (she claims to be of Mapun heritage, also native to Sulu), is also a Christian.

Traditional Political Structure

The political structure of the Tausug is affected by the two economic divisions in the ethnic group, mainly parianon (people of the landing) and guimbahanon (hill people). Before the establishment of the Sultanate of Sulu, the indigenous pre-Islamic Tausug were organized into various independent communities or community-states called banwa. When Islam arrived and the sultanate was established, the banwa was divided into districts administered by a panglima (mayor). The panglima are under the sultan (king). The people who held the stability of the community along with the sultan and the panglimas are the ruma bichura (state council advisers), datu raja muda (crown price), datu maharaja adensuk (palace commander), datu ladladja laut (admiral), datu maharaja layla (commissioner of customes), datu amir bahar (speaker of the ruma bichara), datu tumagong (executive secretary), datu juhan (secretary of information), datu muluk bandarasa (secretary of commerce), datu sawajaan (secretary of interior), datu bandahala (secretary of finance), mamaneho (inspector general), datu sakandal (sultan's personal envoy), datu nay (ordinance or weapon commander), wazil (prime minister). A mangungubat (curer) also has special status in the community as they are believed to have direct contact with the spiritual realm.

The community's people is divided into three classes, which are the nobility (the sultan's family and court), commoners (the free people), and the slaves (war captives, sold into slavery, or children of slaves).

Languages

The Tausug language is called "Sinug" with "Bahasa" to mean Language. The Tausug language is related to Bicolano, Tagalog and Visayan languages, being especially closely related to the Surigaonon language of the provinces Surigao del Norte, Surigao del Sur and Agusan del Sur and the Butuanon language of northeastern Mindanao specially the root Tausug words without the influence of the Arabic language, sharing many common words. The Tausūg, however, do not consider themselves as Visayan, using the term only to refer to Christian Bisaya-language speakers, given that the vast majority of Tausūgs are Muslims in contrast to its very closely related Surigaonon brothers which are predominantly Roman Catholics. Tausug is also related to the Waray-Waray language. Aside from Tagalog (which is spoken throughout the country), a number of Tausug can also speak Zamboangueño Chavacano (especially those residing in Zamboanga City), and other Visayan languages (especially Cebuano language because of the mass influx of Cebuano migrants to Mindanao); Malay in the Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia; and English in both Malaysia and Philippines as second languages.

Malaysian Tausūg, descendants of residents when the Sulu Sultanate ruled the eastern part of Sabah, speak or understand the Sabahan dialect of Suluk, Malaysian language, and some English or Simunul. Those who come in regular contact with the Bajau also speak Bajau dialects. By the year 2000, most of the Tausūg children in Sabah, especially in towns of the west side of Sabah, were no longer speaking Tausūg; instead they speak the Sabahan dialect of Malay and English.

| English | Tausug | Surigaonon | Cebuano |

|---|---|---|---|

| What is your name? | Hisiyu in ngān mu? | Unu an ngayan mu? | Unsa'y ngalan nimo? |

| My name is Muhammad | In ngān ku Muhammad | An ngayan ku ay Muhammad | Ang ngalan nako ay Muhammad |

| How are you? | Maunu-unu nakaw? | Ya-unu nakaw? | Kumusta ka? |

| I am fine, [too] | Marayaw da [isab] | Madayaw da [isab] aku (Tandaganon)/Marajaw da [isab] aku (Surigaonon) | Maayo da/ra [usab] 'ko |

| Where is Ahmad? | Hawnu hi Ahmad? | Hain si Ahmad? | Asa si Ahmad? |

| He is in the house | Ha bāy siya | Sa bay siya/sija | Sa balay siya |

| Thank you | Magsukul | Salamat | Salamat |

| ‘I am staying at’ or ‘I live at’ | Naghuhula’ aku ha | Yaghuya aku sa | Nagpuyo ako sa |

| I am here at the house. | Yari aku ha bay. | Yadi aku sa bay. | Dia ra ko sa balay. |

| I am Hungry. | Hiyapdi' aku. | In-gutom aku. | Gi-gutom ku. |

| He is there, at school. | Yadtu siya ha iskul. | Yadtu siya/sija sa iskul. | Atoa siya sa tunghaan |

| Fish | ista' | isda | isda/ita |

| Leg | Siki | Siki | tiil |

| hand | Lima | Alima | kamut |

| Person | Tau | Tau | Taw/tawo |

| (Sea/River) current | Sūg/Sulug/Suluk | Sūg | Sūg/Sulog |

Cultures

Tausūgs are superb warriors and craftsmen. They are known for the Pangalay dance (also known as Daling-Daling in Sabah), in which female dancers wear artificial elongated fingernails made from brass or silver known as janggay, and perform motions based on the Vidhyadhari (Bahasa Sūg: Bidadali) of pre-Islamic Buddhist legend. The Tausug are also well known for their pis syabit, a multi-colored woven cloth traditionally worn as a headress or accessory by men. Nowadays, the pis syabit is also worn by women and students. In 2011, the pis syabit was cited by the National Commission for Culture and the Arts as one of the intangible cultural heritage of the Philippines under the traditional craftsmanship category that the government may nominate in the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists.[18] The Tausug are additionally associated with tagonggo, a traditional type of kulingtang music.[19]

Tausūg dancers in traditional attire.

Tausūg dancers in traditional attire. Tausūg women in a traditional Tausūg fan dance.

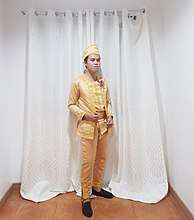

Tausūg women in a traditional Tausūg fan dance. A Tausug man wearing traditional attire that consists of badjuh lapih (upper) and kupat (pants).

A Tausug man wearing traditional attire that consists of badjuh lapih (upper) and kupat (pants). A Tausug woman wearing a sablay.

A Tausug woman wearing a sablay..jpg)

- Kabasi, a Tausūg dish.

- Pis siyabit (headscarf) of the Tausūgs, displayed at the Honolulu Museum of Art.

Notable Tausūgs

.jpg)

- Santanina T. Rasul, first Filipino Muslim woman senator.

- Muedzul Lail Tan Kiram, legitimate Sultan of Sulu Filipino

- Nur Misuari, former Filipino governor and founder of the Moro National Liberation Front.

- Hadji Kamlon, freedom fighter

- Jamalul Kiram III, self-proclaimed Filipino sultan.

- Ismael Kiram II, self-proclaimed Filipino sultan.

- Mat Salleh (Datu Muhammad Salleh), Sabah warrior from Inanam during the British administration of North Borneo.

- Tun Datu Mustapha (Tun Datu Mustapha bin Datu Harun), first Yang di-Pertua Negeri (Governor) of Sabah and third Chief Minister of Sabah.

- Juhar Mahiruddin, tenth Yang di-Pertua Negeri (Governor) of Sabah (also partial Kadazan-Dusun ethnic ancestry).

- Musa Aman, fourteenth Chief Minister of Sabah.

- Shafie Apdal, fifteenth Chief Minister of Sabah.

- Sitti, Filipino singer.

- Maria Lourdes Sereno, 24th Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the Philippines.

- Wawa Zainal Abidin, Malaysian actress.

- Yong Muhajil, YouTube vlogger and 3rd runner up in Pinoy Big Brother: Lucky 7.

- Nelson Dino, novelist, author, short story, prose and poetry writer,[20] a recipient of Sabah Literary Prize 2016-2017 (Hadiah Sastera Sabah 2016-2017) and ASEAN 2 Poetry Competition 100 Best Works.[21] His books are Sulug in Sabah,[22] Pengikat Kasih, Bisikan Bumi, Kita Punya Cara,[23] Sapi Mandangan dan Apuk Daguan,[24] and PIS: Pemikiran dan Identiti Suluk.

- Omar Musa, an award-winning author, poet and rapper from Queanbeyan, New South Wales, Australia. He has released three solo hip hop records (including Since Ali Died) and three books of poetry. His debut novel Here Come the Dogs was published in 2014. Here Come the Dogs was long-listed for the Miles Franklin Award. He was named one of the Sydney Morning Herald’s Young Novelists of the Year in 2015. He is the son of Australian arts journalist Helen Musa and Malaysian poet Musa bin Masran. He is of Suluk, Kedayan and Irish ancestry. He studied at the Australian National University and the University of California, Santa Cruz.

- Dr. Benj Bangahan, Doc Benj, as he is fondly called, is a doctor, writer, philanthropist, event organizer, historian, and a lot more. He is better known as an expert in the Tausug language. However, overarching all these is his identity as a proud Tausug, one who loves his homeland, treasures his culture, and dreams and hopes of a progressive tomorrow for all Tausugs.

- Aziz Kong, a Tausug of Chinese origin from Siasi, and a Tausug vlogger based in Abu Dhabi, who publish vlogs, educational and medical videos in Bahasa Tausug under the YouTube channel name: Amanat hi Akong Kong which means " The message of Akong Kong".

See also

- Yakan people

- Sulug Island

- Bajau people

- Maranao people

Notes

- Most of the native Suluks in Sabah have lived since before the formation of Malaysia. When Malaysia was formed, all of them who lived in the Malaysian soil automatically gained citizenship (like the other races in Sabah) compared to their newly arrival relatives who lived in the Philippines soil at the time and only came to Malaysia after the country been formed.

References

- "2010 Census of Population and Housing, Report No. 2A: Demographic and Housing Characteristics (Non-Sample Variables) - Philippines" (PDF). Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- Jim Haskins (1982). The Filipino Nation: , or Tausug could also mean, strong people from the word "tau" means - people, "sug" from the word " kusug - strong. The Philippines : lands and peoples, a cultural geography. Grolier International. p. 190. ISBN 9780717285099.

- Scott, William Henry (1994). Barangay Sixteenth Century Philippine Culture And Society. Quezon City, Philippines: Ateneo de Manila University Press. p. 164. ISBN 971-550-135-4.

- Zorc, R. David Paul. "Glottolog 3.3 - Tausug". Glottolog. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- Cf. also Paulo Bonavides, Political Sciences (Ciência Política), p. 126.

- "Sabah's People and History". Sabah State Government. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

The Kadazan-Dusun is the largest ethnic group in Sabah that makes up almost 30% of the population. The Bajaus, or also known as "Cowboys of the East", and Muruts, the hill people and head hunters in the past, are the second and third largest ethnic group in Sabah respectively. Other indigenous tribes include the Bisaya, Brunei Malay, Bugis, Kedayan, Lotud, Ludayeh, Rungus, Suluk, Minokok, Bonggi, the Ida'an, and many more. In addition to that, the Chinese makes up the main non-indigenous group of the population.

- Philip Golingai (26 May 2014). "Despised for the wrong reasons". The Star. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- Daphne Iking (17 July 2013). "Racism or anger over social injustice?". The Star. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- Saceda, Charlie (6 March 2013). "Pinoys in Sabah fear retaliation". Rappler. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- Manlupig, Karlos (9 March 2013). "'If you are Tausug, they will arrest you'". Rappler. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- "Deported Filipinos forced to leave families". Al Jazeera. 20 March 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- "11,992 illegals repatriated from Sabah between January and November, says task force director". The Malay Mail. 22 November 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- Jaymalin Mayen (25 March 2014). "Over 26,000 Filipino illegal migrants return from Sabah". The Philippine Star. ABS-CBN News. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- "2010 Census of Population and Housing, Report No. 2A: Demographic and Housing Characteristics (Non-Sample Variables) - Philippines" (PDF). Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- Fausto Barlocco (4 December 2013). Identity and the State in Malaysia. Routledge. pp. 77–85. ISBN 978-1-317-93239-0.

- https://www.scribd.com/doc/49638616/Languages-of-Indonesia Languages-of-Indonesia

- "Tausug Architecture" (PDF). www.ichcap.org. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- "Artists explore state of Filipino art, culture in the diaspora". usa.inquirer.net. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- Utusan Borneo https://www.pressreader.com/malaysia/utusan-borneo-sabah/20180520/282235191315482

- Aliza Alawi http://www.newsabahtimes.com.my/nstweb/fullstory/28042

- Sabah State Library https://sabah.elib.com.my/book/details/73741?lang=malay

- Noorasvilla Muhamma https://www.pressreader.com/malaysia/utusan-borneo-sabah/20180827/282308205964122

- DBP Niaga https://dbpniaga.my/kanak-kanak/2266-cerita-rakyat-sabah-sapi-mandangan-dan-apuk-daguan.html