Environmental racism

Environmental racism is a concept in the environmental justice movement, which developed in the United States throughout the 1970s and 1980s. The term is used to describe environmental injustice that occurs within a racialized context both in practice and policy.[1] In the United States, environmental racism criticizes inequalities between urban and exurban areas after white flight. Internationally, environmental racism can refer to the effects of the global waste trade, like the negative health impact of the export of electronic waste to China from developed countries.

Definition

The term was coined in 1982 by Benjamin Chavis,[2] previous executive director of the United Church of Christ (UCC) Commission for Racial Justice, addressing hazardous polychlorinated biphenyl waste in the Warren County PCB Landfill, North Carolina. Chavis defined the term as:

racial discrimination in environmental policy making, the enforcement of regulations and laws, the deliberate targeting of communities of color for toxic waste facilities, the official sanctioning of the life-threatening presence of poisons and pollutants in our communities, and the history of excluding people of color from leadership of the ecology movements.[3]

The UCC and US General Accounting Office reports on this case in North Carolina associated locations of hazardous waste sites with poor minority neighborhoods.[4][5] Chavis and Robert D. Bullard pointed out institutionalized racism stemming from government and corporate policies that led to environmental racism. Practices included redlining, zoning, and colorblind adaptation planning.[6] Residents experienced environmental racism due to their low socioeconomic status, and lack of political representation and mobility.[7][3] Expanding the definition in "The Legacy of American Apartheid and Environmental Racism," Robert Bullard said that environmental racism

refers to any policy, practice, or directive that differentially affects or disadvantages (whether intended or unintended) individuals, groups, or communities based on race or color.[8]

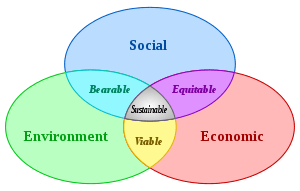

The term “environment” is a term that is understood as it sets where everything takes place. The environment is defined as, “Where we live, work, play, learn and pray”.[9] Most people want equal access to work, recreation, education, religion, and safe neighborhoods. Environmental justice combats inequalities within these services. Greenaction.org explains that, “environmental justice refers to those cultural norms and values, rules, regulations, behaviors, policies, and decisions to support sustainability, where all people can hold with confidence that their community and natural environment is safe and productive.”[9] Environmental racism is a specific form of environmental injustice with which the underlying cause of said injustice is believed to be race-based. [10]

Trying to define environmental racism can be quite difficult. Different communities of people understand the different interactions from different perspectives. Ryan Holifield argues that, “We must accept that people in different geographical, historical, political, and institutional contexts understand the terms differently. Instead of regarding the lack of universal definitions as a barrier to progress, however, we need to treat the breadth and multiplicity of interpretations as guides to more relevant and useful new research”.[11] Environmental justice and social justice can be connected.[12]

There are countless cases where citizens are not experiencing the equity of the environment. There are several different spatial levels where minorities have faced racism which keeps them pinned in difficult situations. “These are structural outcomes in so far as access, entitlements and life expectancy continue to be strongly shaped by people’s racial identities. Most pertinently, the racial dimension of environmental inequality surfaces around the question of who has rights to environmental protection and who bears the burden of waste and pollution.”[13]

Background

Environmental racism can be traced back around 500 years with the arrival of the Europeans and their displacement of Native Americans. The Environmental Justice Movement, however, was rooted around the same time as the Civil Rights Movement. The Civil Rights Movement influenced the mobilization of people by echoing the empowerment and concern associated with political action.[14] Here, the civil rights agenda and the environmental agenda met. However, environmental organizations such as Sierra Club distanced themselves from cases such as the Warren County case likely because of their unwillingness to risk technical support when dealing with a very social issue.[15] The acknowledgement of environmental racism prompted the environmental justice social movement that began in the 1970s and 1980s in the United States.[16] While environmental racism has been historically tied to the environmental justice movement, throughout the years the term has been increasingly disassociated.[17] In response to cases of environmental racism, grassroots organizations and campaigns have brought more attention to environmental racism in policy making and emphasize the importance of having input from minorities in policymaking.[2] Although the term was coined in the US, environmental racism also occurs on the international level. Examples include the exportation of hazardous wastes to poor countries in the Global South with lax environmental policies and safety practices (pollution havens).[7] Marginalized communities that do not have the socioeconomic and political means to oppose large corporations are at risk to environmentally racist practices that are detrimental and sometimes fatal to humans. Economic statuses and political positions are crucial factors when looking at environmental problems because they determine where a person lives.[18]

Causes

One perspective of environmental racism patterns includes the vulnerability of a community to flooding, and its lack of access to potable water, solid waste removal services, and drainage systems.[19]

Environmental racism can also be identified through sociological theories in which covert organized racial and ethnic oppression develops into environmental injustices, or overt racism which limits the right of people of color to make decisions with regard to the environment in which they live.[20]

Another perspective argues that there are four factors which lead to environmental racism: chief among them are lack of affordable land, lack of political power, lack of mobility, and poverty. Cheap land is sought by corporations and governmental bodies. As a result, communities which cannot effectively resist these corporations and governmental bodies and cannot access political power cannot negotiate just costs. Communities with minimized socio-economic mobility cannot relocate. Lack of financial contributions also reduces the communities' ability to act both physically and politically.[21] Chavis defined environmental racism in five categories: racial discrimination in defining environmental policies, discriminatory enforcement of regulations and laws, deliberate targeting of minority communities as hazardous waste dumping sites, official sanctioning of dangerous pollutants in minority communities, and the exclusion of people of color from environmental leadership positions.[22]

Minority communities often do not have the financial means, resources, and political representation to oppose hazardous waste sites.[23] They also may depend on the economic opportunities the site brings and are reluctant to oppose its location at the risk of their health.[24] Additionally, controversial projects are less likely to be sited in non-minority areas that are expected to pursue collective action and succeed in opposing the siting the projects in their area.[25][26]

Processes such as suburbanization, gentrification, and decentralization lead to patterns of environmental racism. For example, the process of suburbanization (or white flight) consists of non-minorities leaving industrial zones for safer, cleaner, and less expensive suburban locales. Meanwhile, minority communities are left in the inner cities and in close proximity to polluted industrial zones. In these areas, unemployment is high and businesses are less likely to invest in area improvement, creating poor economic conditions for residents and reinforcing a social formation that reproduces racial inequality.[27] Furthermore, the poverty of property owners and residents in a municipality may be taken into consideration by hazardous waste facility developers since areas with depressed real estate values will cut expenses.[28]

Socioeconomic aspects of environmental racism

Cost benefit analysis

Cost-benefit analysis (CBA) is a process that places a monetary value on costs and benefits to evaluate issues.[29] Environmental CBA aims to provide policy solutions for intangible products such as clean air and water by measuring a consumer's willingness to pay for these goods. CBA contributes to environmental racism through the valuing of environmental resources based on their utility to society. When someone is willing and able to pay more for clean water or air, their society financially benefits society more than when people cannot pay for these goods. This creates a burden on poor communities. Relocating toxic wastes is justified since poor communities are not able to pay as much as a wealthier area for a clean environment. The placement of toxic waste near poor people lowers the property value of already cheap land. Since the decrease in property value is less than that of a cleaner and wealthier area, the monetary benefits to society are greater by dumping the toxic waste in a "low-value" area.[30]

Devaluation cycle

Research conducted by Professor Been indicates that there are other factors acting on environmental racism.[31] Professor Been's research examined the change in the socioeconomic composition of a surrounding community in Houston after ten noxious facilities were constructed. She found that initially five of the ten facilities were located in areas with above average percentages of non-white residents, while the other five locals had lower percentages of non-white residents. Over time there was a significant shift in demographics. By 1990, nine out of the ten facilities had above average percentages of minority residents; Been then concluded that these results pointed to a case of "white flight". A study conducted by the University of Massachusetts found that when compared to their counterparts, home values fall by $11,000 when they are located by commercial hazardous waste facilities.[32]

Impacts on health

Environmental racism impacts the health of the communities affected by poor environments. Various factors that can cause health problems include exposure to hazardous chemical toxins in landfills and rivers.[33]

In Defense of Animals claims intensive agriculture affects the health of the communities they are near through pollution and environmental injustice. They claim such areas have waste lagoons that produce hydrogen sulfide, higher levels of miscarriages, birth defects, and disease outbreaks from viral and bacterial contamination of drinking water. These farms are disproportionately placed and largely affect low-income areas and communities of color. Because of the socioeconomic status and location of many of these areas, the people affected cannot easily escape these conditions. This includes exposure to pesticides in agriculture and poorly-managed toxic waste dumping to nearby homes and communities from factories disposing of toxic animal waste.[34]

Intensive agriculture also poses a hazard to its workers through high demand velocities, low pay, poor cleanliness in facilities, and other health risks. The workers employed in intensive agriculture are largely composed of minority races and are often near minority communities. Areas that are near factories of this sort are also subjected to contaminated drinking water, toxic fumes, chemical run-off, pollutant particulate matter in the air, and other various harmful risks leading to lessened quality of life and potential disease outbreak.[35]

Minority populations are exposed to greater environmental health risks than white people, according to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). As stated by Greenlining, an advocacy organization based out of Oakland, CA, “[t]he EPA’s National Center for Environmental Assessment found that when it comes to air pollutants that contribute to issues like heart and lung disease, Blacks are exposed to 1.5 times more of the pollutant than whites, while Hispanics were exposed to about 1.2 times the amount of non-Hispanic whites. People in poverty had 1.3 times the exposure of those not in poverty.” [36]

Climate change

As the climate has changed progressively over the past several decades, there has been a collision between environmental racism and global climate change. The overlap of these two phenomena, many argue, has disproportionately affected different communities and populations throughout the world due to disparities in socio-economic status.[37] This is especially true in the Global South where, for example, byproducts of global climate change such as increasingly frequent and severe landslides resulting from more heavy rainfall events in Quito, Ecuador force people to also deal with profound socio-economic ramifications like the destruction of their homes or even death.[38] Countries such as Ecuador often contribute relatively little to climate change in terms of metrics like carbon dioxide emissions but have far fewer resources to ward off the negative localized impacts of climate change. The argument is that places like these are made much more vulnerable than the main contributing countries, but not by their own doing. Some also claim a general attitude of apathy on the part of developed nations and the largest climate change contributors towards the disproportionate effects of their actions on those that contribute relatively much less.[37]

While people living in the Global South have typically been impacted most by the effects of climate change, people of color in the Global North also face similar situations in several areas. The southeastern part of the United States has experienced a large amount of pollution and minority populations have been hit with the brunt of those impacts. One example of this inequality is in so-called "Cancer Alley," an 85-mile area in Louisiana known for its exacerbated cancer rates. [39] Other examples include sugar industry pollution in Pahokee, Florida, paper mills in Africatown, Alabama, PCBs dumped by Burlington Industries in Cheraw, South Carolina, and toxic coal ash in Uniontown, Alabama. Superfund sites, or areas of polluted land that require long-term response to remove hazardous waste contamination, are largely located near low-income housing. An estimated 2 million people, mostly communities of low-income and people of color, live near the Superfund sites most vulnerable to climate change.[40]

The issues of climate change and communities that are in a danger zone are not limited to North America or the United States either. There are several communities around the world that face the same concern of industry and people who are dealing with its negative impacts in their areas. For example, the work of Desmond D’Sa focused on communities in south Durban where high pollution industries impact people forcibly relocated during the Apartheid.[41]

Environmental racism and climate change coincide with one another. Rising seas affect poor areas such as Kivalina, Alaska, and Thibodaux, Louisiana, and countless other places around the globe. There are many cases of people who have died or are chronically ill from coal plants in Detroit, Memphis, and Kansas City, as well as numerous other areas. Tennessee and West Virginia residents are frequently subject to breathing toxic ash due to blasting in the mountains for mining. Drought, flooding, the constant depletion of land and air quality determine the health and safety of the residents surrounding these areas. Communities of color and low-income status most often feel the brunt of these issues firsthand. [42]

Cases of environmental racism by location

North America

United States of America

In the United States, the first report to draw a relationship between race, income, and risk of exposure to pollutants was the Council of Environmental Quality's "Annual Report to the President" in 1971, in response to toxic waste dumping in an African American community in Warren County, NC.[43] After protests in Warren County, North Carolina, the U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) issued a report on the case in 1983, and the United Church of Christ (UCC) commissioned a report exploring the concept in 1987 drawing a connection between race and the placement of the hazardous waste facilities.[4][5][2] The outcry in Warren County was an important event in spurring minority, grassroots involvement in the environmental justice movement by addressing cases of environmental racism.[2]

The US Government Accountability Office study in response to the 1982 protests against the PCB landfill in Warren County was among the first groundbreaking studies that drew correlations between the racial and economic background of communities and the location of hazardous waste facilities. However, the study was limited in scope by only focusing on off-site hazardous waste landfills in the Southeastern United States.[44] In response to this limitation the United Church of Christ Commission for Racial Justice (CRJ) directed a comprehensive national study on demographic patterns associated with the location of hazardous waste sites.[44]

The CRJ national study conducted two examinations of areas surrounding commercial hazardous waste facilities and the location of uncontrolled toxic waste sites.[44] The first study examined the association between race and socio-economic status and the location of commercial hazardous waste treatment, storage, and disposal facilities.[44] After statistical analysis, the first study concluded that "the percentage of community residents that belonged to a racial or ethnic group was a stronger predictor of the level of commercial hazardous waste activity than was household income, the value of the homes, the number of uncontrolled waste sites, or the estimated amount of hazardous wastes generated by industry".[45] The second study examined the presence of uncontrolled toxic waste sites in ethnic and racial minority communities, and found that 3 out of every 5 African and Hispanic Americans lived in communities with uncontrolled waste sites.[46] Other studies found race to be the most influential variable in predicting where waste facilities were located.[47]

From the reports on environmental racism in Warren County, NC, the accumulation of studies and reports on cases of environmental racism and injustices garnered increased public attention in the US. Eventually this led to President Bill Clinton's 1994 Executive Order 12898 which directed agencies to develop a strategy that manages environmental justice, but not every federal agency has fulfilled this order to date.[48][3] This was a historical step in addressing environmental injustice on a policy level, especially within a predominantly white-dominated environmentalism movement; however, the effectiveness of the Order is noted mainly in its influence on states as Congress never pass a bill making Clinton's Executive Order law.[49] The issuance of the Order propelled states into action as many states began to require relevant agencies to develop strategies and programs that would identify and address environmental injustices being perpetrated at the state or local level.[50]

In 2005, during George W. Bush's administration, there was an attempt to remove the premise of racism from the Order. EPA's Administrator Stephen Johnson wanted to redefine the Order's purpose to shift from protecting low income and minority communities that may be disadvantaged by government policies to all people. President Barack Obama's appointment of Lisa Jackson as EPA Administrator and the issuance of Memorandum of Understanding on Environmental Justice and Executive Order 12898 established a recommitment to environmental justice.[51] The fight against environmental racism faced some setbacks with the election of President Trump. Under Trump's administration, there was a mandated decrease of EPA funding accompanied by a rollback on regulations which has left many underrepresented communities vulnerable.[52]

As a result of the placement of hazardous waste facilities, minority populations experience greater exposure to harmful chemicals and suffer from health outcomes that affect their ability at work and in schools. A comprehensive study of particulate emissions across the United States, published in 2018, found that Blacks were exposed to 54% more particulate matter emissions (soot) than the average American.[53][54] Faber and Krieg found a correlation between higher air pollution exposure and low performance in schools and found that 92% of children at five Los Angeles public schools with the poorest air quality were of a minority background.[55][56] School systems for communities heavily populated with minority families tend to provide "unequal educational opportunities" in comparison to school systems in predominantly white neighborhoods.[57] Pollution consequently presents itself in these communities due to societal factors such as "underfunded schools, income inequality, and myriad egregious denials of institutional support" within the African American community.[58] In a study supporting the term of environmental racism, it was shown in the American Mid-Atlantic and American North-East that African Americans were exposed to 61% of particulate matter, while Latinos were exposed to 75%, and Asians were exposed to 73%. Overall, these populations experience 66% more pollution exposure from particulate matter than the white population.[59]

When environmental racism became acknowledged in the US society, it stimulated the environmental justice social movement that gained wave throughout the 1970s and 1980s in the US. Historically, the term environmental racism is tied to environmental justice movement. However, this has changed with time to the extent it is believed to lack any associations with the movement. Grassroots organizations and campaigns have sprung up in response to this environmental racism with these groups mainly demanding the inclusion of minorities when it comes to policy making involving the environment. It is also worth noting that this concept is international despite being coined in the US. A perfect example is when the United States exported its hazardous wastes to the poor nations in the Global South because they knew that these countries had lax environmental regulations and safety practices. Marginalized communities are usually at risk of environmental racism because they resource and means to oppose the large companies that dump these dangerous wastes.[60]

Overall, the US has worked to reduce environmental racism with municipality changes.[61] These policies help develop further change. Some cities and counties have taken advantage of environmental justice policies and applied it to the public health sector.[62]

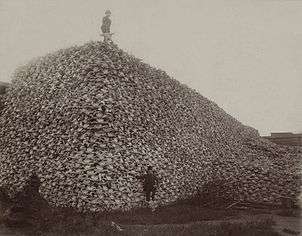

Native American reservations

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 and the Trail of Tears may be considered early examples of environmental racism in the United States. As a result of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, by 1850, all tribes east of the Mississippi had been removed to western lands, essentially confining them to "lands that were too dry, remote, or barren to attract the attention of settlers and corporations." [63] During World War II, military facilities were often located conterminous to reservations, leading to a situation in which "a disproportionate number of the most dangerous military facilities are located near Native American lands." [64] A study analyzing the approximately 3,100 counties in the continental United States found that Native American lands are positively associated with the count of sites with unexploded ordnance deemed extremely dangerous. The study also found that the risk assessment code (RAC) used to measure dangerousness of sites with unexploded ordnance can sometimes conceal how much of a threat these sites are to Native Americans. The hazard probability, or probability that a hazard will harm people or ecosystems, is sensitive to the proximity of public buildings such as schools and hospitals. These parameters neglect elements of tribal life such as subsistence consumption, ceremonial use of plants and animals, and low population densities. Because these tribal-unique factors are not considered, Native American lands can often receive low-risk scores, despite threat to their way of life. The hazard probability does not take Native Americans into account when considering the people or ecosystems that could be harmed. Locating military facilities coterminous to reservations lead to a situation in which “a disproportionate number of the most dangerous military facilities are located near Native American lands.” [63]

More recently, Native American lands have been used for waste disposal and illegal dumping by the US and multinational corporations.[65][66] The International Tribunal of Indigenous People and Oppressed Nations, convened in 1992 to examine the history of criminal activity against indigenous groups in the United States,[67] and published a Significant Bill of Particulars outlining grievances indigenous peoples had with the US. This included allegations that the US "deliberately and systematically permitted, aided, and abetted, solicited and conspired to commit the dumping, transportation, and location of nuclear, toxic, medical, and otherwise hazardous waste materials on Native American territories in North America and has thus created a clear and present danger to the health, safety, and physical and mental well-being of Native American People." [67]

An ongoing issue for Native Americans activists is the Dakota Access Pipeline. The pipeline was proposed to start in North Dakota and travel to Illinois. Although it does not cross directly on a reservation, the pipeline is under scrutiny because it passes under a section of the Missouri river which is the main drinking water source for the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. Pipelines are known to break, with the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) reporting more than 3,300 leak and rupture incidents for oil and gas pipelines since 2010. The pipeline also traverses a sacred burial ground for the Standing Rock Sioux.[68] The Tribal Historic Preservation Officer of the Standing Rock Sioux tribe voiced concerns related to sacred sites and archaeological materials. These concerns were ignored. President Barack Obama revoked the permit for the project in December 2016 and ordered a study on rerouting the pipeline. President Donald Trump reversed this order and authorized the completion of the pipeline.[69] In 2017, Judge James Boasberg sided with the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, citing the US Army Corps of Engineers failure to complete a study on the environmental impact of an oil spill in Lake Oahe when it first approved construction. A new environmental study was ordered and released in October 2018, but the pipeline remained operational.[69][70] The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe rejected the study, believing it fails to address many of their concerns. There are still ongoing litigation efforts by the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe opposing the Dakota Access Pipeline in an effort to shut it down permanently.[71]

Illinois

Environmental racism is especially prominent in large cities as well. The city of Chicago, Illinois, has had difficulties around industry and its impacts on minority populations, especially the African American community. For example, the Crawford and Fisk coal plants have been implicated in the poor health of their local communities, a correlation exacerbated by the fact that 34% of adults in those communities do not have health care coverage. [72]

One community directly affected by a toxic environment due to racial discrimination is Altgeld Gardens, a 6,000 unit public housing community located in south Chicago that was built in 1945 on an abandoned landfill to accommodate returning African American World War II veterans. Surrounded by 53 toxic facilities and 90% of the city's landfills, the Altgeld Gardens area became known as a "toxic doughnut." [73] In Altgeld Gardens, 90% of its population are African-American and 65% live below the poverty level.[74] The known toxins and pollutants affecting the Altgeld Gardens area include mercury, ammonia gas, lead, dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), heavy metals, and xylene. [74]

In 1984, a study by Illinois Public Health Sector revealed excessive rates of prostate, bladder, and lung cancer. [75] Additionally, as reported in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development's seminar on social and environment interface, medical records have indicated high rates of children born with brain tumors, high rates of fetuses that had to be aborted after tests revealed that the brains were developing outside the skull, and higher rates of asthma, ringworm, and other ailments. Despite evidence of health problems caused by environmental factors, the residents of Altgeld Gardens have not been relocated to another public housing project.[75]

In Chicago's predominantly Latino neighborhoods such as Little Village, the array coal plants were contributors to respiratory diseases and other health complications during the early twenty-first century.[76] In addition to air pollution, Little Village lacked safe outdoor recreational areas while housing a County Jail that occupied 96 acres.[77] Despite widespread displeasure among community members, activists were afraid to speak out because their neighborhood could be gentrified. Many Latino neighborhoods are populated by working class citizens vulnerable to the increased cost of living caused by gentrification. [78] Some advocates still fought for environmental improvements regardless of their fear, and when their requests began to come to fruition, like the eventual increase in local green spaces, many residents were left feeling out of place in their homes, which could be attributed to shifts in factors like local police presences, local racial diversity, and overall class of the townsfolk.[79]

California

The city of Los Angeles, California is facing concerns much like several other areas in the United States. As in many cases, poor areas and underdeveloped communities that are most prone to pollution and the impacts of climate change also happen to be the areas where minority populations are the highest. In the case of Los Angeles, the most prevalent minority population at risk is the Hispanic community. This community has shown significant concern about climate change because they are the most likely to live in impacted areas. [80] The City Project aims to examine burden populations and how to provide aid or better planning and development. [81] The environmental injustices in Los Angeles became known roughly thirty or forty years ago and minority communities remain at risk today from city planning that happened just a few decades ago. [82]

The Civil Rights Act (CRA) was used in the 1994 lawsuit against the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transit Authority which failed to provide services for poor LA County residents.[83] In response to fatal diesel pollution in the air around ports in Los Angeles and Long Beach in 2006, the San Pedro Bay Ports Clean Air Action Plan, or CAAP, was passed.[84] The action plan was created to reduce pollution caused by ports; specifically, it demanded a 45% decrease in pollution once the proposal was put into action.[85] Another layer of the plan's objective was to reduce negative environmental impacts from trucks with the initial plans for the Clean Truck Program (CTP), which intended to cut back on the use of shipping trucks from the docks and instead called for purer options like rail yards and warehouses that could hopefully improve the air quality.[85]

Louisiana

Diamond, a small African American community, filed a lawsuit against Shell gas company after years of experiencing toxic emissions from the neighboring refinery.[86] Shell offered to buy out the homes that the residents owned, however, the property value was so low that residents could not get new housing. Eventually after protesting and making the issue a public matter, Shell eventually agreed to relocate the residents.[87]

In 1989, the Louisiana Energy Services (LES), a British, German and American conglomerate, conducted a nationwide search to find the "best" site to build a privately owned uranium enrichment plant. The LES claimed to use an objective scientific method to select Louisiana as the "best" place to build the plant. In response to the selection, the communities of Homer, Forest Grove and Center Springs that are nearby the proposed site formed a group called Citizens Against Nuclear Trash (CANT). With the help of the Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund (later changed to Earth Justice Legal Defense Fund), CANT sued LES for practicing environmental racism. Finally after 8 years, on May 1, 1997, a three-judge panel of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission's Atomic Safety and Licensing Board found that racial bias did play a role in the selection process. In response to the victory, the London Times declared, "Louisiana Blacks Win Nuclear War." The courts decision was also upheld on appeal on April 4, 1998.[88]

At the time of Hurricane Katrina, 60.5% of New Orleans residents were African American. Pre-existing racial disparities in wealth within New Orleans worsened the outcome of Hurricane Katrina for minority populations. Institutionalized racial segregation of neighborhoods meant minority members were more likely to live in low-lying areas vulnerable to flooding.[89][90] Additionally, hurricane evacuation plans relied heavily on the use of cars and did not prepare for people who relied on public transportation.[91] Because minority populations are less likely to own cars, some people had no choice but to stay behind, while white majority communities escaped. A report commissioned by the U.S. House of Representatives found that political leaders failed to consider the fact that "100,000 city residents had no cars and relied on public transit" and the city's failure to complete its mandatory evacuation led to hundreds of deaths.[92]

In the months following the disaster, political, religious, and civil rights groups, celebrities, and New Orleans residents spoke out against what they believed was racism on the part of the United States government.[93] After the hurricane, in a meeting held between the Congressional Black Caucus, the National Urban League, the Black Leadership Forum, the National Council of Negro Women, and the NAACP, Black leaders criticized the response of the federal government calling it "slow and incomplete" and discussed the role of race in this response.[94] With rising sea levels, lack of mobility of non-white populations in coastal cities like New Orleans foreshadow future unequal impacts of climate change and natural disasters on minority communities.[95]

.jpg)

Michigan

Since April 2014, residents of Flint, Michigan, a city that is almost 57% Black and notably impoverished, have been drinking and bathing in water that contains enough lead to meet the Environmental Protection Agency's definition of "toxic waste." Before 2014 when the city of Flint switched to their own river as means of water, Lake Huron provided the area with water. Researchers at Virginia Tech discovered in 2015 that the Flint River is 19 times more corrosive than Lake Huron. Lead contamination can engender multiple health conditions. A November 2015 class-action lawsuit describes how Michigan's Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) failed to treat the new water source with an anti-corrosive agent, thereby causing the water to become increasingly discolored. This was in violation of the Lead and Copper Rule and MDEQ did not correctly complete the Safe Drinking Water Act mandated lead assessments.[96] Adding that agent (orthophosphate) would have cost $100 per day, according to CNN, and 90 percent of the problems with Flint's water would have been averted if it had been used.[97]

Apart from lead leached from plumbing fixtures, other sources of lead contamination include dust from lead-based paints and use of tetraethyl lead in gasoline, both of which have been phased out in many countries.[98]

After an official investigation was conducted, Michigan's attorney general Bill Schuette initially filed charges against three government officials: two state officials of the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality, Michael Prysby and Stephen Busch, and a Flint city employee, Michael Glasglow, who was the city's water quality supervisor. They were brought up against felony charges such as "misconduct, neglect of duty, and conspiracy to tamper with evidence." [99] They were also charged with violating the Michigan Safe Water Drinking Act. [99] All the charges were dropped against these defendants, and all the others investigated or charged, except for those against Corinne Miller, who had worked in the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services. On September 14, 2016, Miller pleaded no contest to the neglect of duty charge and agreed to testify against the other defendants. [100] She was later sentenced to a year probation, 300 hours of community service, and fined $1,200.[101]

On April 16, 2020, an article was published giving details of evidence of corruption and a coverup by former Governor Rick Snyder and his “fixer” Rich Baird, and stating that the statute of limitations on some of the most serious felony misconduct-in-office charges would expire on April 25, 2020. The article was published by Vice News, written by Jordan Chariton and Jenn Dize, the co-founders of Status Coup, with photos by Brittany Greeson.[102] Responses from Michigan state authorities denied that a deadline was approaching, and said that criminal prosecutions would follow. [103] [104]

North Carolina

Racism and environmental justice unified for the first time during the 1983 citizen opposition to a proposed PCB landfill in Warren County, North Carolina.[105] North Carolina state officials decided to bury soil contaminated with toxic polychlorinated biphenyls in Afton, a small town in Warren County, despite such an action being illegal.[106] As a result, between June 1978 and August 1978, 30,000 gallons (114 m³) of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB)-contaminated waste were deposited along 210 miles of North Carolina roads. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) declared the PCBs a threat to public health and required the state to remove the polluted waste. In 1979, the North Carolina Department of Environment and Natural Resources and EPA Region 4 selected Warren County as the site to deposit the PCB-contaminated soil that was collected from the roadsides.[105] Warren County is one of the six counties along the "black belt" of North Carolina. The counties residing in the "black belt" are significantly poorer than the rest of the state. In the early 1980s the residents in Warren County earned an average per capita income of $6,984 compared to $9,283 for the rest of the state.[106] In 1980, the population of Warren County was 54.5% African-American.[105]

In 1982, the local National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) filed a lawsuit in the district courts to block the landfill. The residents lost the case in court.[105] In September 1982, the outraged citizens of Warren County joined by civil rights groups, environmental leaders, and clergymen protested the first truckloads of PCB-contaminated soil.[107] During the protest, over 500 people were arrested and jailed. Despite protests and scientific evidence that the plan would cause drinking water contamination, the Warren County PCB Landfill was built and the toxic waste was placed in the landfill.[107][108] After nearly two decades of suspected leaks, state and federal sources paid a contractor $18 million to detoxify the PCB contaminated soil in Warren County.[105] Warren County is often cited as the first environmental justice case in the United States; however, this movement started years earlier in 1978 with the discovery of toxic waste in Love Canal, New York.[109]

North Carolina is home to 31 coal ash pits that store an expected 111 million tons of harmful waste created by coal-fired power plants. It is also home to many excrement pits, referred to indirectly as "lagoons," that store roughly 10 billion pounds of wet waste created every year by swine, poultry, and dairy cattle in the state.[110] Many of North Carolina's hog farms are grouped along the coastal plain, with a high percentage of African-American residents.[110]

The coastal city of Wilmington has been repeatedly threatened by hurricanes, and its environmental risks are increased by its proximity to hog farms, Brunswick Nuclear Generating Station, and coal-ash pits—one of which has already spilled over, due to Hurricane Florence in September 2018.[111] Hog waste spills can be destructive to the individuals who live close to these pits and farms and a significant number of the neighbors are low-income ethnic minorities. In 1971, racial strains over the absence of protection for African Americans resulted in the arrest of several black activists who came to be known as the "Wilmington Ten." One of those activists, Benjamin Chavis, would later turn into a significant figure in the environmental justice movement.[111] Two epidemiologists at the University of North Carolina at Sanctuary Slope distributed a paper in 2014 titled: "Industrial Hog Operations in North Carolina Excessively Effect African-Americans, Hispanics and Native Americans."[112]

Pennsylvania

Chester, Pennsylvania, provides an example of "social, political, and economic forces that shape the disproportionate distribution of environmental hazards in poor communities of color." [113] Chester is located in Delaware County, an area with a population of 500,000 that, excluding Chester, is 91% White. Chester, however, is 65% African American, with the highest minority population and poverty rate in Delaware County,[114] and recipient of a disproportionate amount of environmental risks and hazards.[115] Chester has five large waste facilities including a trash incinerator, a medical waste incinerator, and a sewage treatment plant. [114] These waste sites in Chester have a total permitted capacity of 2 million tons of waste per year while the rest of Delaware County has a capacity of merely 1,400 tons per year.[116] One of the waste sites located in Chester is the Westinghouse incinerator, which burns all of the municipal waste from the entire county and surrounding states.[113] These numerous waste facilities engender very significant health risks to the citizens of Chester, as the cancer rate in this area is 2.5 times higher than it is anywhere else in Pennsylvania.[117] The mortality rate is 40% higher than the rest of Delaware County.[113]

Texas

San Antonio's Kelly Air Force Base (KAFB) is one of the Air Force's major aircraft maintenance facilities and takes up 4000 acres of land, surrounded by residential neighborhoods of primarily Hispanic populations. KAFB maintains various parts of aircraft such as jet engines, and accessory components and even nuclear materials, generating as much as 282,000 tons of hazardous waste each year.[118] Residents of the nearby communities have complained many times of unusual illnesses their children have experienced as well as respiratory illnesses and kidney disease.[119][120] A 1997 survey done in the residential neighborhoods close to KAFB showed 91% of adults and 79% of children are suffering from conditions ranging from nose, ear, and throat issues to central nervous system disorders. Scientists released information in 1983 revealing that toxic waste had been dumped into an uncovered pit from 1960 to 1973. The waste in the pit contained various chemicals, such as PCBs and DDT, that contaminated groundwater.[121]

West Virginia

Mexico

Mexico City

On November 19, 1984, the San Juanico disaster caused thousands of deaths and roughly a million injuries in poor surrounding neighborhoods. The disaster occurred at the PEMEX liquid propane gas plant in a densely populated area of Mexico City. The close proximity of illegally built houses that did not meet regulations worsened the effects of the explosion.[122][123]

U.S.-Mexico Water Rights and Indigenous People

The Cucapá are a group of indigenous people that live near the U.S.-Mexico border, mainly in Mexico but some in Arizona as well. For many generations, fishing on the Colorado River was the Cucapá's main means of subsistence.[124] In 1944, the United States and Mexico signed a treaty that effectively awarded the United States rights to about 90% of the water in the Colorado River, leaving Mexico with the remaining 10%.[125] Over the last few decades the Colorado River has mostly dried up south of the border, presenting many challenges for people such as the Cucapá. Shaylih Meuhlmann, author of the ethnography Where the River Ends: Contested Indigeneity in the Mexican Colorado Delta, gives a first-hand account of the situation from Meuhlmann's point of view as well as many accounts from the Cucapá themselves. In addition to the Mexican portion of the Colorado River being left with a small fraction of the overall available water, the Cucapá are stripped of the right to fish on the river, the act being made illegal by the Mexican government in the interest of preserving the river's ecological health.[124] The Cucapá are, thus, living without access to sufficient natural sources of freshwater as well as without their usual means of subsistence. The conclusion drawn in many such cases is that the negotiated water rights under the US-Mexican treaty that lead to the massive disparity in water allotments between the two countries boils down to environmental racism.

Canada

In Canada, progress is being made to address environmental racism (especially in Nova Scotia's Africville community) with the passing of Bill 111, An Act to Address Environmental Racism in the Nova Scotia Legislature.[83]

Europe

France

Exporting toxic wastes to countries in the Global South is one form of environmental racism that occurs on an international basis. In one alleged instance, the French aircraft carrier Clemenceau was prohibited from entering Alang, an Indian ship-breaking yard, due to a lack of clear documentation about its toxic contents. French President Jacques Chirac ultimately ordered the carrier, which contained tons of hazardous materials including asbestos and PCBs, to return to France.[126]

United Kingdom

In the UK environmental racism (or also climate racism) has been called out by multiple action groups such as the Wretched of the Earth call out letter[127] in 2015 and Black Lives Matter in 2016.[128]

The Netherlands

In the Netherlands environmental racism was campaigned against in 2017 with regard to shipping dirty diesel from Amsterdam and Rotterdam harbor to Africa. The diesel contained 100 times more sulfur than is allowed by European regulation. It was shipped to African countries where lives are less protected and pollution is less regulated.

Italy

Romani people, Eastern Europe

Predominantly living in Central and Eastern Europe, with pockets of communities in the Americas and Middle East, the ethnic Romani people have been subjected to environmental exclusion. Often referred to as gypsies or the gypsy threat, the Romani people of Eastern Europe mostly live under the poverty line in shanty towns or slums.[129] Facing issues such as long term exposure to harmful toxins given their locations to waste dumps and industrial plants, along with being refused environmental assistance like clean water and sanitation, the Romani people have been facing racism via environmental means. Many countries such has Romania, Bulgaria and Hungary have tried to implement environmental protection initiatives across their respected countries, however most have failed due to "addressing the conditions of Roma communities have been framed through an ethnic lens as “Roma issues."[130] Only recently has some form of environmental justice for the Romani people come to light. Seeking environmental justice in Europe, the Environmental Justice Program is now working with human rights organizations to help fight environmental racism.

It is important to note that in the "Discrimination in the EU in 2009" report, conducted by the European Commission, "64% of citizens with Roma friends believe discrimination is widespread, compared to 61% of citizens without Roma friends."[131]

Oceania

Micronesia

Australia

The Australian Environmental Justice (AEJ) is a multidisciplinary organization which is closely partnered with Friends of the Earth Australia (FoEA). The AEJ focuses on recording and remedying the effects of environmental injustice throughout Australia. The AEJ has addressed issues which include "production and spread of toxic wastes, pollution of water, soil and air, erosion and ecological damage of landscapes, water systems, plants and animals".[132] The project looks for environmental injustices that disproportionately affect a group of people or impact them in a way they did not agree to.

The Western Oil Refinery started operating in Bellevue, Western Australia in 1954. It was permitted rights to operate in Bellevue by the Australian government in order to refine cheap and localized oil. In the decades following, many residents of Bellevue claimed they felt respiratory burning due to the inhalation of toxic chemicals and nauseating fumes. Lee Bell from Curtin University and Mariann Lloyd-Smith from the National Toxic Network in Australia stated in their article, "Toxic Disputes and the Rise of Environmental Justice in Australia" that "residents living close to the site discovered chemical contamination in the ground- water surfacing in their back yards".[133] Under immense civilian pressure, the Western Oil Refinery (now named Omex) stopped refining oil in 1979. Years later, citizens of Bellevue formed the Bellevue Action Group (BAG) and called for the government to give aid towards the remediation of the site. The government agreed and $6.9 million was allocated to clean up the site. Remediation of site began in April 2000.

Papua New Guinea

Starting production in 1972, the Panguna mine in Papua New Guinea has been a source of environmental racism. Although closed since 1989 due to conflict on the island, the indigenous peoples (Bougainvillean) have suffered both economically and environmentally from the creation of the mine. Terrance Wesley-Smith and Eugene Ogan, University of Hawaii and University of Minnesota respectively, stated that the Bougainvillean's "were grossly disadvantaged from the beginning and no subsequent renegotiation has been able to remedy the situation".[134] These indigenous people faced issues such as losing land which could have been used for agricultural practices for the Dapera and Moroni villages, undervalued payment for the land, poor relocation housing for displaced villagers and significant environmental degradation in the surrounding areas.[135]

Asia

China

From the mid-1990s until about 2001, it is estimated that some 50 to 80 percent of the electronics collected for recycling in the western half of the United States was being exported for dismantling overseas, predominantly to China and Southeast Asia.[136][137] This scrap processing is quite profitable and preferred due to an abundant workforce, cheap labour, and lax environmental laws.[138][139]

Guiyu, China is one of the largest recycling sites for e-waste, where heaps of discarded computer parts rise near the riverbanks and compounds, such as cadmium, copper, lead, PBDEs, contaminate the local water supply.[140][141] Water samples taken by the Basel Action Network in 2001 from the Lianjiang River contained lead levels 190 times higher than WHO safety standards.[139] Despite contaminated drinking water, residents continue to use contaminated water over expensive trucked-in supplies of drinking water.[139] Nearly 80 percent of children in the e-waste hub of Guiyu, China, suffer from lead poisoning, according to recent reports.[142] Before being used as the destination of electronic waste, most of Guiyu was composed of small farmers who made their living in the agriculture business.[143] However, farming has been abandoned for more lucrative work in scrap electronics.[143] "According to the Western press and both Chinese university and NGO researchers, conditions in these workers' rural villages are so poor that even the primitive electronic scrap industry in Guiyu offers an improvement in income".[144]

India

.svg.png)

Union Carbide Corporation, is the parent company of Union Carbide India Limited which outsources its production to an outside country. Located in Bhopal, India, Union Carbide India Limited primarily produced the chemical methyl isocyanate used for pesticide manufacture.[145] On December 3, 1984, a cloud of methyl isocyanate leaked as a result of the toxic chemical mixing with water in the plant in Bhopal.[146] Approximately 520,000 people were exposed to the toxic chemical immediately after the leak.[145] Within the first 3 days after the leak an estimated 8,000 people living within the vicinity of the plant died from exposure to the methyl isocyanate.[145] Some people survived the initial leak from the factory, but due to improper care and improper diagnoses many have died.[145] As a consequence of improper diagnoses, treatment may have been ineffective and this was precipitated by Union Carbide refusing to release all the details regarding the leaked gases and lying about certain important information.[145] The delay in supplying medical aid to the victims of the chemical leak made the situation for the survivors even worse.[145] Many today are still experiencing the negative health impacts of the methyl isocyanate leak, such as lung fibrosis, impaired vision, tuberculosis, neurological disorders, and severe body pains.[145]

The operations and maintenance of the factory in Bhopal contributed to the hazardous chemical leak. The storage of huge volumes of methyl isocyanate in a densely inhabited area, was in contravention with company policies strictly practiced in other plants.[147] The company ignored protests that they were holding too much of the dangerous chemical for one plant and built large tanks to hold it in a crowded community.[147] Methyl isocyanate must be stored at extremely low temperatures, but the company cut expenses to the air conditioning system leading to less than optimal conditions for the chemical.[147] Additionally, Union Carbide India Limited never created disaster management plans for the surrounding community around the factory in the event of a leak or spill.[147] State authorities were in the pocket of the company and therefore did not pay attention to company practices or implementation of the law.[147] The company also cut down on preventive maintenance staff to save money.[147]

South America

Ecuador

Due to their lack of environmental laws, emerging countries like Ecuador have been subjected to environmental pollution, sometimes causing health problems, loss of agriculture, and poverty. In 1993, 30,000 Ecuadorians, which included Cofan, Siona, Huaorani, and Quichua indigenous people, filed a lawsuit against Texaco oil company for the environmental damages caused by oil extraction activities in the Lago Agrio oil field. After handing control of the oil fields to an Ecuadorian oil company, Texaco did not properly dispose of its hazardous waste, causing great damages to the ecosystem and crippling communities.[148]

Mapuche-Chilean Land Conflict

Beginning in the late 15th century when European explorers began sailing to the New World, the violence towards and oppression of indigenous populations have had lasting effects to this day. The Mapuche-Chilean land conflict has roots dating back several centuries. When the Spanish went to conquer parts of South America, the Mapuche were one of the only indigenous groups to successfully resist Spanish domination and maintain their sovereignty[149]. Moving forward, relations between the Mapuche and the Chilean state declined into a condition of malice and resentment. Chile won its independence from Spain in 1818 and, wanting the Mapuche to assimilate into the Chilean state, began crafting harmful legislation that targeted the Mapuche.[150] The Mapuche have based their economy, both historically and presently, on agriculture. By the mid-19th century, the state resorted to outright seizure of Mapuche lands, forcefully appropriating all but 5% of Mapuche lineal lands[150]. An agrarian economy without land essentially meant that the Mapuche no longer had their means of production and subsistence. While some land has since been ceded back to the Mapuche, it is still a fraction of what the Mapuche once owned. Further, as the Chilean state has attempted to rebuild its relationship with the Mapuche community, the connection between the two is still strained by the legacy of the aforementioned history.[149]

Today, the Mapuche people are the largest population of indigenous people in Chile, with 1.5 million people accounting for over 90% of the country's indigenous population.[150]

Africa

Nigeria

In Nigeria, near the Niger Delta, cases of oil spills, burning of toxic waste, and urban air pollution are problems in more developed areas. In the early 1990s, Nigeria was among the 50 nations with the world's highest levels of carbon dioxide emissions, which totaled 96,500 kilotons, a per capita level of 0.84 metric tons. The UN reported in 2008 that carbon dioxide emissions in Nigeria totaled 95,194 kilotons.[151]

Numerous webpages were created in support of the Ogoni people, who are indigenous to Nigeria's oil-rich Delta region. Sites were used to protest the disastrous environmental and economic effects of Shell Oil drilling, to urge the boycotting of Shell Oil, and to denounce human rights abuses by the Nigerian government and by Shell. The use of the Internet in formulating an international appeal intensified dramatically after the Nigerian government's November 1995 execution of nine Ogoni activists, including Ken Saro-Wiwa, who was one of the founders of the nonviolent Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP).[152]

South Africa

The linkages between the mining industry and the negative impacts it has on community and individual health has been studied and well-documented by a number of organizations worldwide. Health implications of living in proximity to mining operations include effects such as pregnancy complications, mental health issues, various forms of cancer, and many more.[153] During the Apartheid period in South Africa, the mining industry grew quite rapidly as a result of the lack of environmental regulation. Communities in which mining corporations operate are usually those with high rates of poverty and unemployment. Further, within these communities, there is typically a divide among the citizens on the issue of whether the pros of mining in terms of economic opportunity outweigh the cons in terms of the health of the people in the community. Mining companies often try to use these disagreements to their advantage by magnifying this conflict. Additionally, mining companies in South Africa have close ties with the national government, skewing the balance of power in their favor while simultaneously excluding local people from many decision-making processes.[154] This legacy of exclusion has had lasting effects in the form of impoverished South Africans bearing the brunt of ecological impacts resulting from the actions of, for example, mining companies. Some argue that to effectively fight environmental racism and achieve some semblance of justice, there must also be a reckoning with the factors that form situations of environmental racism such as rooted and institutionalized mechanisms of power, social relations, and cultural elements.[155]

The term “energy poverty” is used to refer to “a lack of access to adequate, reliable, affordable and clean energy carriers and technologies for meeting energy service needs for cooking and those activities enabled by electricity to support economic and human development”. Numerous communities in South Africa face some sort of energy poverty. [156] South African women are typically in charge of taking care of both the home and the community as a whole. Those in economically impoverished areas not only have to take on this responsibility, but there are numerous other challenges they face. Discrimination on the basis of gender, race, and class are all still present in South African culture. Because of this, women, who are the primary users of public resources in their work at home and for the community, are often excluded from any decision-making about control and access to public resources. The resulting energy poverty forces women to use sources of energy that are expensive and may be harmful both to their own health and that of the environment. Consequently, several renewable energy initiatives have emerged in South Africa specifically targeting these communities and women to correct this situation.[156]

Addressing environmental racism

Activists have called for "more participatory and citizen-centered conceptions of justice." [157][158] The environmental justice (EJ) movement and climate justice (CJ) movement address environmental racism in bringing attention and enacting change so that marginalized populations are not disproportionately vulnerable to climate change and pollution.[83][159] According to the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, one possible solution is the precautionary principle, which states that "where there are threats of serious or irreversible damage, lack of full scientific certainty shall not be used as a reason for postponing cost-effective measures to prevent environmental degradation." [160] Under this principle, the initiator of the potentially hazardous activity is charged with demonstrating the activity's safety. Environmental justice activists also emphasize the need for waste reduction in general, which would act to reduce the overall burden.[158]

Concentrations of ethnic or racial minorities may also foster solidarity, lending support in spite of challenges and providing the concentration of social capital necessary for grassroots activism. Citizens who are tired of being subjected to the dangers of pollution in their communities have been confronting the power structures through organized protest, legal actions, marches, civil disobedience, and other activities.[161]

Racial minorities are often excluded from politics and urban planning (such as sea level rise adaptation planning) so various perspectives of an issue are not included in policy making that may affect these excluded groups in the future.[159] In general, political participation in African American communities is correlated with the reduction of health risks and mortality.[162] Other strategies in battling against large companies include public hearings, the elections of supporters to state and local offices, meetings with company representatives, and other efforts to bring about public awareness and accountability.[163]

In addressing this global issue, activists take to various social media platforms to both raise awareness and call to action. The mobilization and communication between the intersectional grassroots movements where race and environmental imbalance meet has proven to be effective. The movement gained traction with the help of Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat among other platforms. Celebrities such as Shailene Woodley, who advocated against the Keystone XL Pipeline, have shared their experiences including that of being arrested for protesting. Social media has allowed for a facilitated conversation between peers and the rest of the world when it comes to social justice issues not only online but in face-to-face interactions correspondingly.[164]

Studies

Studies have been important in drawing associations and public attention by exposing practices that cause marginalized communities to be more vulnerable to environmental health hazards. Deserting the Perpetrator-Victim Model of studying environmental justice issues, the Economic/Environmental Justice Model utilized a sharper lens to study the many complex factors, accompanied to race, that contributes to the act of environmental racism and injustice. For example, Lerner not only revealed the role of race in the division of Diamond and Norco residents, but he also revealed the historical roles of the Shell Oil Company, the slave ancestry of Diamond residents, and of the history of white workers and families that were dependent upon the rewards of Shell. [165] Involvement of outside organizations, such as the Bucket Brigade and Greenpeace, was also considered in the power that the Diamond community had when battling for environmental justice.

In wartimes, environmental racism occurs in ways that the public later learn about through reports. For example, Friends of the Earth International's Environmental Nakba report brings attention to environmental racism that has occurred in the Gaza Strip during the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict. Some Israeli practices include cutting off three days of water supply to refugee Palestinians and destroying farms.[166]

Besides studies that point out cases of environmental racism, studies have also provided information on how to go about changing regulations and preventing environmental racism from happening. In a study by Daum, Stoler and Grant on e-waste management in Accra, Ghana, the importance of engaging with different fields and organizations such as recycling firms, communities, and scrap metal traders are emphasized over adaptation strategies such as bans on burning and buy-back schemes that have not caused much effect on changing practices.[167][168]

Studies have also shown that since environmental laws have become prominent in developed countries, companies have moved their waste towards the Global South. Less developed countries have fewer environmental policies and therefore are susceptible to more discriminatory practices. Although this has not stopped activism, it has limited the effects activism has on political restrictions.[169]

Procedural Justice

Current political ideologies surrounding how to make right issues of environmental racism and environmental justice are shifting towards the idea of employing procedural justice. Procedural justice is a concept that dictates the use of fairness in the process of making decisions, especially when said decisions are being made in diplomatic situations such as the allocation of resources or the settling of disagreements. Procedural justice calls for a fair, transparent, impartial decision-making process with equal opportunity for all parties to voice their positions, opinions, and concerns.[170] Rather than just focusing on the outcomes of agreements and the effects those outcomes have on affected populations and interest groups, procedural justice looks to involve all stakeholders throughout the process from planning through implementation. In terms of combating environmental racism, procedural justice helps to reduce the opportunities for powerful actors such as often-corrupt states or private entities to dictate the entire decision-making process and puts some power back into the hands of those who will be directly affected by the decisions being made.[169]

Activism

Activism takes many forms. One form is collective demonstrations or protests, which can take place on a number of different levels from local to international. Additionally, in places where activists feel as though governmental solutions will work, organizations and individuals alike can pursue direct political action. In many cases, activists and organizations will form partnerships both regionally and internationally to gain more clout in pursuit of their goals.[171]

Before the 1970s, communities of color recognized the reality of environmental racism and organized against it. For example, the Black Panther Party organized survival programs that confronted the inequitable distribution of trash in predominantly black neighborhoods.[172] Similarly, the Young Lords, a Puerto Rican revolutionary nationalist organization based in Chicago and New York City, protested pollution and toxic refuse present in their community via the Garbage Offensive program. These and other organizations also worked to confront the unequal distribution of open spaces, toxic lead paint, and healthy food options.[173] They also offered health programs to those affected by preventable, environmentally induced diseases such as tuberculosis.[173] In this way, these organizations serve as precursors to more pointed movements against environmental racism.

Latino ranch laborers composed by Cesar Chavez battled for working environment rights, including insurance from harmful pesticides in the homestead fields of California's San Joaquin Valley. In 1967, African-American understudies rioted in the streets of Houston to battle a city trash dump in their locale which had killed two kids. In 1968, occupants of West Harlem, in New York City, battled unsuccessfully against the siting of a sewage treatment plant in their neighborhood.[174]

Efforts of activism have also been heavily influenced by women and the injustices they face from environmental racism. Women of different races, ethnicities, economic status, age, and gender are disproportionately affected by issues of environmental injustice. Additionally, the efforts made by women have historically been overlooked or challenged by efforts made by men, as the problems women face have been often avoided or ignored. Winona LaDuke is one of many female activists working on environmental issues, in which she fights against injustices faced by indigenous communities. LaDuke was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 2007 for her continuous leadership towards justice.

Policies and international agreements

The export of hazardous waste to third world countries is another growing concern. Between 1989 and 1994, an estimated 2,611 metric tons of hazardous waste was exported from Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries to non-OECD countries. Two international agreements were passed in response to the growing exportation of hazardous waste into their borders. The Organization of African Unity (OAU) was concerned that the Basel Convention adopted in March 1989 did not include a total ban on the trans-boundary movement on hazardous waste. In response to their concerns, on January 30, 1991, the Pan-African Conference on Environmental and Sustainable Development adopted the Bamako Convention banning the import of all hazardous waste into Africa and limiting their movement within the continent. In September 1995, the G-77 nations helped amend the Basel Convention to ban the export of all hazardous waste from industrial countries (mainly OECD countries and Lichtenstein) to other countries.[175] A resolution was signed in 1988 by the OA) which declared toxic waste dumping to be a “crime against Africa and the African people”.[176] Soon after, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) passed a resolution that allowed for penalties, such as life imprisonment, to those who were caught dumping toxic wastes. [176]

Globalization and the increase in transnational agreements introduce possibilities for cases of environmental racism. For example, the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) attracted US-owned factories to Mexico, where toxic waste was abandoned in the Colonia Chilpancingo community and was not cleaned up until activists called for the Mexican government to clean up the waste.[177]

Environmental justice movements have grown to become an important part of world summits. This issue is gathering attention and features a wide array of people, workers, and levels of society that are working together. Concerns about globalization can bring together a wide range of stakeholders including workers, academics, and community leaders for whom increased industrial development is a common denominator”.[178]

Many policies can be expounded based on the state of human welfare. This occurs because environmental justice is obviously aimed at creating safe, fair, and equal opportunity for communities and to ensure things like redlining do not occur. [179] With all of these unique elements in mind, there are serious ramifications for policy makers to consider when they make decisions.

See also

- Environmental struggles of the Romani

- Climate change and poverty

- Electronic waste

- Environmental justice

- Global environmental inequality

- Internalized racism

- Netherlands fallacy

- NIMBY

- Environmental dumping

- Health inequality and environmental influence

- Intergenerational equity

- Environmental discrimination in the United States

References

- Bullard, Robert D (2001). "Environmental Justice in the 21st Century: Race Still Matters". Phylon. 49 (3–4): 151–171. doi:10.2307/3132626.

- Perez, Alejandro; Grafton, Bernadette; Mohai, Paul; Harden, Rebecca; Hintzen, Katy; Orvis, Sara (2015). "Evolution of the environmental justice movement: activism, formalization and differentiation". Environmental Research Letters. 10 (10): 105002. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/10/10/105002.

- Mohai, Paul; Pellow, David; Roberts, J. Timmons (2009). "Environmental Justice". Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 34: 405–430. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-082508-094348.

- Chavis, Jr., Benjamin F., and Charles Lee, "Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States," United Church of Christ Commission for Racial Justice, 1987

- Office, U.S. Government Accountability (1983-06-14). "Siting of Hazardous Waste Landfills and Their Correlation With Racial and Economic Status of Surrounding Communities" (RCED-83–168).

- Hardy, Dean; Milligan, Richard; Heynen, Nik (2017). "Racial coastal formation: The environmental injustice of colorblind adaptation planning for sea-level rise". Geoforum. 87: 62–72. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.10.005.

- Park, Rozelia (1998). "An Examination of International Environmental Racism Through the Lens of Transboundary Movement of Hazardous Wastes". Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies. 5 – via Jerome Hall Law Library.

- Bullard, Robert (Spring 1994). "The Legacy of American Apartheid and Environmental Racism". Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development. 9 – via St. John's University School of Law.

- "Environmental Justice & Environmental Racism – Greenaction for Health and Environmental Justice". Retrieved 2020-02-24.

- Fritz, Jan M. (1999). "Searching for EnvironmentalJustice: National Stories,Global Possibilities". Social Justice. 26: 175.

- Holifield, Ryan (2013-05-16). "Defining Environmental Justice and Environmental Racism". Urban Geography. 22: 78–90. doi:10.2747/0272-3638.22.1.78. ISSN 0272-3638.

- Westra, Laura; Lawson, Bill; Lawson, Bill E.; Wenz, Peter S. (2001). Faces of Environmental Racism: Confronting Issues of Global Justice. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-1249-8.

- Newell, Peter. "Race, Class and the Global Politics of Environmental Inequality" (PDF).

- Cole, Luke W.; Foster, Sheila R. (2001). From the Ground Up: Environmental Racism and the Rise of the Environmental Justice Movement. NYU Press. ISBN 9780814715376.

- McGurty, Eileen Maura (1997). "From NIMBY to Civil Rights: The Origins of the Environmental Justice Movement". Environmental History. 2 (3): 301–323. doi:10.2307/3985352. JSTOR 3985352.

- Melosi, Martin (1995). "Equity, eco-racism and environmental history". Environmental History Review. 19 (3): 1–16. doi:10.2307/3984909.

- Ulezaka, Tara. Race and Waste: The Quest for Environmental Justice. Temple Journal of Science Technology & Environmental Law.

- Dicochea, Perlita R. (2012). "Discourses of Race & Racism within Environmental Justice Studies: An Eco-Racial Intervention". Ethnicity and Race in a Changing World. 3 (2): 18–29 – via ProQuest.

- Harper, Krista; Steger, Tamara; Filčák, Richard (July 2009). "Environmental justice and Roma communities in Central and Eastern Europe". Environmental Policy and Governance. 19 (4): 251–268. doi:10.1002/eet.511.

- Saha, Robin. 2010. "Environmental Racism". In Encyclopedia of Geography, ed. Barney Warf, Sage Publications, doi:10.4135/9781412939591.n379

- Park, Rozelia (1998-04-01). "An Examination of International Environmental Racism Through the Lens of Transboundary Movement of Hazardous Wastes". Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies 659 (1998). 5 (2): 659–709. JSTOR 25691124.

- Holifield, Ryan (2001). "Defining Environmental Justice and Environmental Racism.". Urban Geography. Milwaukee: V. H. Winston & Son, Inc. pp. 78–90.

- Colquette, Kelly Michele; Henry Robertson, Elizabeth A. (1991). "Environmental Racism: The Causes, Consequences, and Commendations". Tulane Environmental Law Journal. 5 (1): 168.

- Bullard, Robert D.; Mohai, Paul; Saha, Robin; Wright, Beverly (March 2007). Toxic Wastes and Race at Twenty: 1987-2007 (PDF) (Report). United Church of Christ. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-07-09. Retrieved 2008-03-28.

- Fisher M. 1995. Environmental Racism Claims brought under the Title VI of the Civil Rights Act.

- Bryant, Bunyan. "Introduction." Environmental justice issues, policies, and solutions. Washington, D.C: Island, 1995. 1-7.

- Pulido, Laura (2000). "Rethinking Environmental Racism: White Privilege and Urban Development in Southern California". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 90 (1): 12–40. doi:10.1111/0004-5608.00182. hdl:10214/1833.

- Colquette and Robertson, 174.

- "Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA)", World Bank Group. n.d. Accessed: November 20, 2011.

- Westra, Laura, and Bill E. Lawson. Faces of Environmental Racism: Confronting Issues of Global Justice. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2001.