Early modern Netherlandish cartography

This article covers the science and art of cartography by the (especially Dutch-speaking) people of the Low Countries in the early modern period, especially in the early 16th to early 18th centuries. It also includes cartography of the Netherlands (i.e. history of surveying and creation of maps of the Netherlands) and cartography of the Low Countries in general (i.e. history of surveying and creation of maps of the Low Countries).

In the history of cartography, especially in the 16th–18th centuries, early modern Netherlandish (Dutch and Flemish) cartography,[lower-alpha 1] both as science and art, has a very special place. From both national and international perspectives, early modern Netherlandish cartographers (and geographers) played a highly significant historical role — who helped shape cartographic, geographic, navigational, cosmographic and astronomical knowledge of the modern-day world as we know today.

The period of late 16th and much of the 17th century (approximately 1570s–1670s) has been called the "Golden Age of Netherlandish (Dutch and Flemish) cartography". During the Golden Age of Netherlandish cartography, mapmaking firms of Antwerp and Amsterdam, especially, dominated the art and industry of cartography in the civilized world. They were leaders in supplying maps and charts for almost all of Europe. As James A. Welu (1987) notes, "For roughly a century, from 1570 to 1670, mapmakers working in the Low Countries brought about unprecedented advances in the art of cartography. The maps, charts, and globes issued during this period, at first mainly in Antwerp and later in Amsterdam, are distinguished not only by their accuracy according to the knowledge of the time, but also by their richness of ornamentation, a combination of science and art that has rarely been surpassed in the history of mapmaking."[1]

.jpg)

Origins

Until the fall of Antwerp (1585), the Dutch and Flemish were generally seen as one people.[lower-alpha 2] The center for cartographic activities in sixteenth-century Low Countries was Antwerp, a city of printers, booksellers, engravers, and artists. But Leuven was the center of learning and the meeting place of scholars and students at the university. Mathematics, globemaking, and instrumentmaking were practiced in and around the University of Leuven as early as the first decades of the sixteenth century. The university is the oldest in the Low Countries and the oldest center of both scientific and practical cartography. Without the influence of several outstanding scholars of the Leuven University (such as Gemma Frisius, Gerardus Mercator, and Jacob van Deventer), cartography in the Low Countries would not have attained the quality and exerted the influence that it did.[2]

Notable figures of the Netherlandish school of cartography and geography (1500s–1600s) include: Franciscus Monachus, Gemma Frisius, Gaspard van der Heyden, Gerard Mercator, Abraham Ortelius, Christophe Plantin, Lucas Waghenaer, Jacob van Deventer, Willebrord Snell, Hessel Gerritsz, Petrus Plancius, Jodocus Hondius, Henricus Hondius II, Hendrik Hondius I, Willem Blaeu, Joan Blaeu, Johannes Janssonius, Andreas Cellarius, Gerard de Jode, Cornelis de Jode, Michiel van Langren, Claes Visscher, Nicolaes Visscher I, Nicolaes Visscher II, and Frederik de Wit. Leuven, Antwerp, and Amsterdam were the main centres of the Netherlandish school of cartography in its golden age (the 16th and 17th centuries, approximately 1570–1670s). The Golden Age of Netherlandish cartography that was inaugurated in the Southern Netherlands (current Belgium; mainly in Leuven and Antwerp) by Mercator and Ortelius found its fullest expression during the seventeenth century with the production of monumental multi-volume atlases in the Dutch Republic (mainly in Amsterdam) by competing mapmaking firms such as Lucas Waghenaer, Joan Blaeu, Jan Janssonius, Claes Janszoon Visscher, and Frederik de Wit.[3]

During the Golden Age of Dutch exploration (c. 1590s–1720s) and the Golden Age of Dutch/Netherlandish cartography (c. 1570s–1670s), Dutch-speaking navigators, explorers, and cartographers were the firsts to chart/map many hitherto largely unknown regions of the earth and the sky. During roughly a century, Netherlandish (Dutch and Flemish) cartographers made important contributions to the science and art of mapmaking. Their publications are remarkable milestones in the history of cartography, the extant editions are not only valuable sources of contemporary geographic knowledge but also fine works of art. The main role in this was played by a special artistic atmosphere of the Netherlands (or the Low Countries) in the 16th and 17th centuries. The Low Countries experienced cultural and economic booms that was combined with enthusiasm of different classes of people for geography and maps. The unique atmosphere made mapmaking a form of art. Cartography and visual arts were related activities: art and mapmaking interacted with each other: many cartographic elements, such as images, colour, and lettering, were shared with art; tools and methods used to produce maps and artistic works were very similar in printmaking and in mapmaking: copperplate engravings, which were hand coloured in later, required specific artistic skills; a significant number of both little-known and the most outstanding artists were involved in decorating maps; maps and art works were often performed by the same artists, engravers and publishers who worked for both areas; artists, engravers and mapmakers belonged to the same group of society that determined the development of culture in many areas.

Gemma Frisius was the first to propose the use of a chronometer to determine longitude in 1530. In his book On the Principles of Astronomy and Cosmography (1530), Frisius explains for the first time how to use a very accurate clock to determine longitude.[4] The problem was that in Frisius' day, no clock was sufficiently precise to use his method. In 1761, the British clock-builder John Harrison constructed the first marine chronometer, which allowed the method developed by Frisius. Triangulation had first emerged as an efficient method in cartography (mapmaking) in the mid sixteenth century when Frisius set out the idea in his Libellus de locorum describendorum ratione (Booklet concerning a way of describing places). Dutch scientists Jacob van Deventer and Willebrord Snell were among the firsts to make systematic use of triangulation in modern surveying, the technique whose theory was described by Frisius in his 1533 book. Gerardus Mercator is considered as one of the founders of modern cartography with his invention of Mercator projection. Mercator was the first to use the term 'atlas' (in a geographical context) to describe a bound collection of maps through his own collection entitled "Atlas sive Cosmographicae meditationes de fabrica mvndi et fabricati figvra" (1595). The hypothesis that continents might have 'drifted' was first put forward by Abraham Ortelius in 1596.

Rise to the golden age and decline

Southern Netherlands (Flanders, Habsburg Netherlands)

Gerardus Mercator: Birth of Mercator projection and the concept of atlas

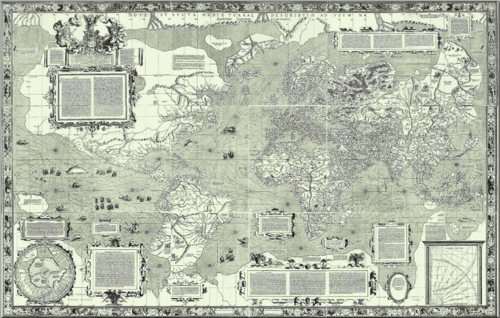

Gerardus Mercator, the German-Netherlandish[5] cartographer and geographer with a vast output of wall maps, bound maps, globes and scientific instruments but his greatest legacy was the mathematical projection he devised for his 1569 world map.

The Mercator projection is an example of a cylindrical projection in which the meridians are straight and perpendicular to the parallels. As a result, the map has a constant width and the parallels are stretched east–west as the poles are approached. Mercator's insight was to stretch the separation of the parallels in a way which exactly compensates for their increasing length, thus preserving shapes of small regions, albeit at the expense of global distortion. Such a conformal map projection necessarily transforms rhumb lines, sailing courses of a constant bearing, into straight lines on the map thus greatly facilitating navigation. That this was Mercator's intention is clear from the title: Nova et Aucta Orbis Terrae Descriptio ad Usum Navigantium Emendate Accommodata which translates as "New and more complete representation of the terrestrial globe properly adapted for use in navigation". Although the projection's adoption was slow, by the end of the seventeenth century it was in use for naval charts throughout the world and remains so to the present day. Its later adoption as the all-purpose world map was an unfortunate step.[6]

Mercator spent the last thirty years of his life working on a vast project, the Cosmographia;[7] a description of the whole universe including the creation and a description of the topography, history and institutions of all countries. The word atlas makes its first appearance in the title of the final volume: "Atlas sive cosmographicae meditationes de fabrica mundi et fabricati figura".[8] This translates as Atlas OR cosmographical meditations upon the creation of the universe, and the universe as created, thus providing Mercator's definition of the term atlas. These volumes devote slightly less than one half of their pages to maps: Mercator did not use the term solely to describe a bound collection of maps. His choice of title was motivated by his respect for Atlas "King of Mauretania"[9]

Abraham Ortelius: Hypothesis of continental drift and the era of modern world atlases

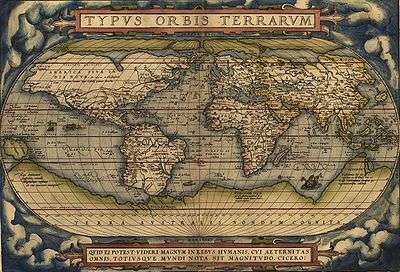

Abraham Ortelius generally recognized as the creator of the world's first modern atlas, the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (Theatre of the World). Ortelius's Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (1570) is considered the first true atlas in the modern sense: a collection of uniform map sheets and sustaining text bound to form a book for which copper printing plates were specifically engraved. It is sometimes referred to as the summary of sixteenth-century cartography.[10][11][12][13]

Northern Netherlands (Dutch Republic and Dutch Empire)

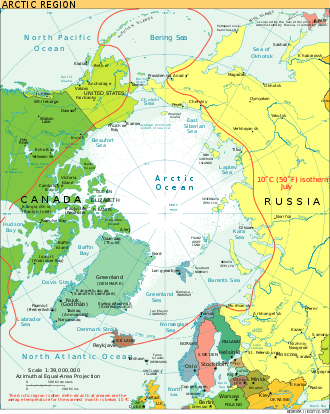

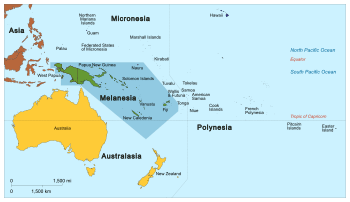

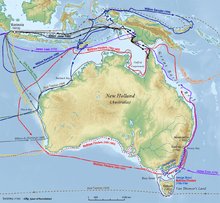

During the Age of Discovery (the Dutch Golden Age in particular, approximately 1580s–1702), using their expertise in doing business, cartography, shipbuilding, seafaring and navigation, the Dutch traveled to the far corners of the world, leaving their language embedded in the names of many places.[14][15] Dutch exploratory voyages revealed largely unknown landmasses to the civilized world and put their names on the world map. In the 16th and 17th centuries, Dutch-speaking cartographers[16] helped lay the foundations for the birth and development of modern cartography, including nautical cartography and stellar cartography (celestial cartography). The Dutch-speaking people came to dominate the map making and map printing industry by virtue of their own travels, trade ventures, and widespread commercial networks.[17] The Dutch initiated what we would call today the free flow of geographical information. As Dutch ships reached into the unknown corners of the globe, Dutch cartographers incorporated new discoveries into their work. Instead of using the information themselves secretly, they published it, so the maps multiplied freely. The Dutch were the first (non-natives) to undisputedly discover, explore and map many unknown isolated areas of the world such as Svalbard, Australia,[18] New Zealand, Tonga, Sakhalin,[19] and Easter Island. In many cases the Dutch were the first Europeans the natives would encounter.[20] Australia (originally known as New Holland), never became a permanent Dutch settlement,[21] yet the Dutch were the first to undisputedly map its coastline. The Dutch navigators charted almost three-quarters of the Australian coastline, except the east coast. During the Age of Exploration, the Dutch explorers and cartographers were also the first to systematically observe and map (chart) the largely unknown far southern skies – the first significant scientific addition to the celestial cartography since Ptolemy's time (2nd century AD). Among the IAU's 88 modern constellations, there are 15 Dutch-created constellations, including 12 southern constellations.[22][23][24]

Gemma Frisius, Jacob van Deventer, Willebrord Snell: Rise of triangulation as a mapmaking method

Triangulation had first emerged as a map-making method in the mid sixteenth century when Gemma Frisius set out the idea in his Libellus de locorum describendorum ratione (Booklet concerning a way of describing places).[25][26][27][28][29][30] Dutch cartographer Jacob van Deventer was among the first to make systematic use of triangulation, the technique whose theory was described by Gemma Frisius in his 1533 book.

The modern systematic use of triangulation networks stems from the work of the Dutch mathematician Willebrord Snell (born Willebrord Snel van Royen), who in 1615 surveyed the distance from Alkmaar to Bergen op Zoom, approximately 70 miles (110 kilometres), using a chain of quadrangles containing 33 triangles in all.[31][32][33] The two towns were separated by one degree on the meridian, so from his measurement he was able to calculate a value for the circumference of the earth – a feat celebrated in the title of his book Eratosthenes Batavus (The Dutch Eratosthenes), published in 1617. Snell's methods were taken up by Jean Picard who in 1669–70 surveyed one degree of latitude along the Paris Meridian using a chain of thirteen triangles stretching north from Paris to the clocktower of Sourdon, near Amiens.

Lucas Waghenaer and the rise of Dutch maritime cartography

The first printed atlas of nautical charts (De Spieghel der Zeevaerdt or The Mirror of Navigation / The Mariner's Mirror) was produced by Lucas Janszoon Waghenaer in Leiden in 1584. This atlas was the first attempt to systematically codify nautical maps. This chart-book combined an atlas of nautical charts and sailing directions with instructions for navigation on the western and north-western coastal waters of Europe. It was the first of its kind in the history of maritime cartography, and was an immediate success. The English translation of Waghenaer's work was published in 1588 and became so popular that any volume of sea charts soon became known as a "waggoner" (an atlas book of engraved nautical charts with accompanying printed sailing directions), the Anglicized form of Waghenaer's surname.[34][35][36][37][38][39][40]

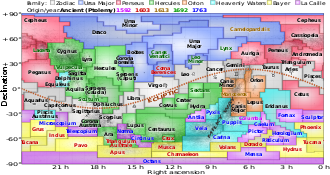

Dutch celestial and lunar cartography in the Age of Discovery

The constellations around the South Pole were not observable from north of the equator, by the ancient Babylonians, Greeks, Chinese, Indians, or Arabs. During the Age of Exploration, expeditions to the southern hemisphere began to result in the addition of new constellations. The modern constellations in this region were defined notably by Dutch navigators Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser and Frederick de Houtman,[42][43][44][45][46] who in 1595 traveled together to the East Indies (first Dutch expedition to Indonesia). These 12 newly Dutch-created southern constellations (that including Apus, Chamaeleon, Dorado, Grus, Hydrus, Indus, Musca, Pavo, Phoenix, Triangulum Australe, Tucana and Volans) first appeared on a 35-cm diameter celestial globe published in 1597/1598 in Amsterdam by Dutch cartographers Petrus Plancius and Jodocus Hondius. The first depiction of these constellations in a celestial atlas was in Johann Bayer's Uranometria of 1603.

In 1660, German-born Dutch cartographer Andreas Cellarius' star atlas (Harmonia Macrocosmica) was published by Johannes Janssonius in Amsterdam.

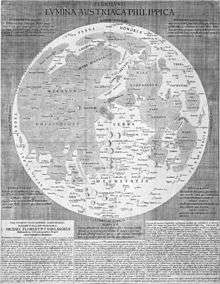

In 1645, Dutch-born Michiel van Langren published the first known map of the Moon with a nomenclature.[47][48]

Competing mapmaking firms in the age of corporate cartography

The Dutch dominated the commercial cartography (corporate cartography) during the seventeenth century through the publicly traded companies (such as the Dutch East India Company and the Dutch West India Company) and the competing privately held map-making houses/firms. In the book Capitalism and Cartography in the Dutch Golden Age (University of Chicago Press, 2015), Elizabeth A. Sutton explores the fascinating but previously neglected history of corporate (commercial) cartography during the Dutch Golden Age, from ca. 1600 to 1650. Maps were used as propaganda tools for both the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and the Dutch West India Company (WIC/GWIC) in order to encourage the commodification of land and an overall capitalist agenda.

In the long run the competition between map-making firms Blaeu and Janssonius resulted in the publication of an 'Atlas Maior' or 'Major Atlas'. In 1662 the Latin edition of Joan Blaeu's Atlas Maior appeared in eleven volumes and with approximately 600 maps. In the years to come French and Dutch editions followed in twelve and nine volumes respectively. Purely judging from the number of maps in the Atlas Maior, Blaeu had outdone his rival Johannes Janssonius. And also from a commercial point of view it was a huge success. Also due to the superior typography the Atlas Maior by Blaeu soon became a status symbol for rich citizens. Costing 350 guilders for a non-coloured and 450 guilders for a coloured version, the atlas was the most precious book of the 17th century. However, the Atlas Maior was also a turning point: after that time the role of Dutch cartography (and Netherlandish cartography in general) was finished. Janssonius died in 1664 while a great fire in 1672 destroyed one of Blaeu's print shops. In that fire a part of the copperplates went up in flames. Fairly soon afterwards Joan Blaeu died, in 1673. The almost 2,000 copperplates of Janssonius and Blaeu found their way to other publishers.

Gallery

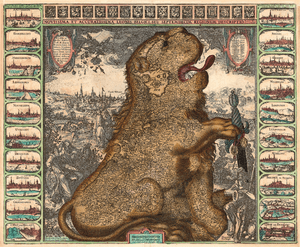

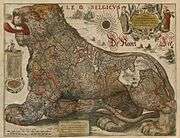

Leo Belgicus by Hondius & Gerritsz, 1630

Leo Belgicus by Hondius & Gerritsz, 1630 Leo Belgicus (1650), published by Claes Jansz Visscher

Leo Belgicus (1650), published by Claes Jansz Visscher Michiel van Langren's map of the Moon, 1645. Van Langren was an early-modern pioneer in the history of lunar cartography (mapping of the Moon) and selenography.

Michiel van Langren's map of the Moon, 1645. Van Langren was an early-modern pioneer in the history of lunar cartography (mapping of the Moon) and selenography. Harmonia Macrocosmica by Andreas Cellarius, 1660

Harmonia Macrocosmica by Andreas Cellarius, 1660_-_KBR_27-8-2016_11-33-21.jpg) Atlas Cosmographicae (Mercator's 1595 World Atlas), in the collection of the Royal Library of Belgium

Atlas Cosmographicae (Mercator's 1595 World Atlas), in the collection of the Royal Library of Belgium_and_Surrounding_Countries_by_Dutch_%E8%8D%B7%E8%98%AD%E4%BA%BA%E6%89%80%E7%B9%AA%E7%A6%8F%E7%88%BE%E6%91%A9%E6%B2%99%E8%87%BA%E7%81%A3.jpeg) 1635 Map of Dutch Formosa and surrounding countries

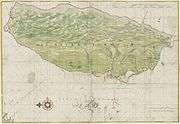

1635 Map of Dutch Formosa and surrounding countries 1640 Map of Dutch Formosa

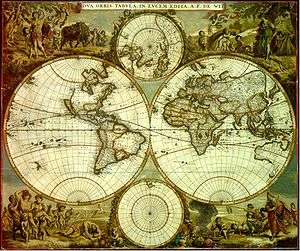

1640 Map of Dutch Formosa Nova Orbis Tabula in Lucem Edita by Frederik de Wit, c. 1665

Nova Orbis Tabula in Lucem Edita by Frederik de Wit, c. 1665 Celestial map by Frederik de Wit, 1670

Celestial map by Frederik de Wit, 1670- Map of the world produced in 1689 by Gerard van Schagen

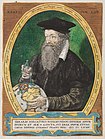

Portrait of Gemma Frisius by Maarten van Heemskerck, c. 1540–1545

Portrait of Gemma Frisius by Maarten van Heemskerck, c. 1540–1545 Portrait of Gerardus Mercator by Frans Hogenberg, 1574

Portrait of Gerardus Mercator by Frans Hogenberg, 1574 Portrait of Abraham Ortelius by Peter Paul Rubens, 1633

Portrait of Abraham Ortelius by Peter Paul Rubens, 1633 Portrait of Petrus Plancius (1791)

Portrait of Petrus Plancius (1791)

Legacy and recognition

An asteroid is named for Gerardus Mercator. On 5 March 2015, Google celebrated his 503rd birthday with a doodle.

On 20 May 2018, Google Doodle celebrated the anniversary of Ortelius' atlas which was published on May 20, 1570.

Crater Langrenus, on the Moon, is named after Michiel van Langren.

Field of (early modern) Netherlandish cartographic and geographic studies

Some notable scholars/historians of Netherlandish cartography and geography include Cornelis Koeman,[52] Peter van der Krogt, Günter Schilder,[53][54][55][56][57] Benjamin Schmidt,[58] Elizabeth A. Sutton,[59][60][61] Claudia Swan, and Kees Zandvliet.[62][63]

- Professional organizations:

- Explokart (research programme at Utrecht University)

- The Brussels Map Circle (previously the Brussels International Map Collectors' Circle)

- Caert-Thresoor: Tijdschrift voor de Geschiedenis van de Kartografie (Dutch-language journal)

See also

- Atlas Blaeu-Van der Hem

- Atlas Cosmographicae (Mercator's 1596 World Atlas)

- Atlas Maior

- Atlas Van Loon

- Dutch celestial cartography in the Age of Discovery (Early systematic mapping of the far southern sky, c. 1595–1599)

- Dutch mapping of Australia (1606–1642)

- Dutch mapping of Formosa (Taiwan)

- Dutch maritime cartography in the Age of Discovery

- Harmonia Macrocosmica

- History of cartography

- Leo Belgicus

- List of Dutch discoveries

- List of Dutch explorations

- List of place names of Dutch origin

- Mercator's 1569 World Map

- Mercator-Hondius Atlas

- Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (Theater of the Whole World)

- The Mariner's Mirror (journal), takes its name from Waghenaer's sea atlas

Notes

- The English adjective "Netherlandish", meaning "from the Low Countries", derived directly from the Dutch adjective Nederlands. Apart from its use to describe paintings, it is as adjective not common in English. It is typically used in reference to paintings or music produced anywhere in the Low Countries during the 15th and early 16th century, which are collectively called Early Netherlandish painting (Dutch: Vlaamse primitieven, "Flemish primitives" — also common in English before the mid 20th century), or (regarding music) the Netherlandish School. Later art and artists from the southern Catholic provinces of the Low Countries are usually called Flemish and those from the northern Protestant provinces Dutch, but art historians sometimes use "Netherlandish art" for art of the Low Countries produced before 1830, i.e., until the secession of Belgium from the Netherlands.

- Frisians, specifically West Frisians, are an ethnic group; present in the North of the Netherlands; mainly concentrating in the Province of Friesland. Culturally, modern Frisians and the (Northern) Dutch are rather similar; the main and generally most important difference being that Frisians speak West Frisian, one of the three sub-branches of the Frisian languages, alongside Dutch.

West Frisians in the general do not feel or see themselves as part of a larger group of Frisians, and, according to a 1970 inquiry, identify themselves more with the Dutch than with East or North Frisians. Because of centuries of cohabitation and active participation in Dutch society, as well as being bilingual, the Frisians are not treated as a separate group in Dutch official statistics. - Including some notable figures of the Netherlandish school of cartography in its golden age (c. 1570s–1670s) like Petrus Plancius, Willem Blaeu, Johannes Blaeu, and Hessel Gerritsz were the official cartographers to the VOC.

References

- Welu, James A. (1987). The Sources and Development of Cartographic Ornamentation in the Netherlands, in Art and Cartography: Six Historical Essays, edited by David Woodward, University of Chicago Press, p. 147–173

- Koeman, Cornelis; Schilder, Günter; van Egmond, M.; van der Krogt, Peter: Commercial Cartography and Map Production in the Low Countries, 1500–ca. 1672 (Part 2: Low Countries), pp. 1296–1383, David Woodward ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007)

- Carhart, George S.: Frederick de Wit and the First Concise Reference Atlas. (BRILL, 2016, ISBN 9789004299030)

- Allaby, Michael (2009). Oceans: A Scientific History of Oceans and Marine Life (Discovering the Earth)

- See the discussion in Gerardus Mercator#The question of nationality.

- See the discussion in Mercator projection#Uses

- See the discussion in Gerardus Mercator#Duisburg 1552–1594

- See the discussion in Gerardus Mercator#atlas1595.

- See the preface to the 1595 posthumous section of Mercator's atlas as translated in Sullivan (2000), pp34–38 (PDF pp103–108)

- Thrower, Norman J. W. (2008). Maps and Civilization: Cartography in Culture and Society, Third Edition, p. 81

- Harwood, Jeremy (2006). To the Ends of the Earth: 100 Maps that Changed the World, p. 83

- Woodward, David (1987). Art and Cartography: Six Historical Essays, p. 148

- Goffart, Walter (2003). Historical Atlases: The First Three Hundred Years, 1570–1870, p. 1

- Gottlieb, Mark (30 August 2006). "Continental Drifter – Dutch Treat: An unlikely nation in an unlikely corner of Europe boasts a remarkable record of unlikely achievement". IndustryWeek. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- McCloskey, Deirdre (17 March 2011). "Chapter 9 of the Bourgeois Revaluation: The Dutch Preached Bourgeois Virtue". Deirdremccloskey.com. Archived from the original on 2014-04-19. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

The Dutch became in the High Middle Ages the tutors of the Northerners in trade and navigation. They taught the English how to say skipper, cruise, schooner, lighter, yacht, wiveling, yaw, yawl, sloop, tackle, hoy, boom, jib, bow, bowsprit, luff, reef, belay, avast, hoist, gangway, pump, buoy, dock, freight, smuggle, and keelhaul. In the last decade of the sixteenth century the busy Dutch invented a broad-bottomed ship ideal for commerce, the fluyt, or fly-boat, and the German Ocean became a new Mediterranean, a watery forum of the Germanic speakers – of the English, Scots, Norse, Danish, Low German, Frisian, Flemish, and above all the Dutch – who showed the world how to be bourgeois.

- including Southern Netherlands-based (Zuid-Nederlanders in Dutch) cartographers and geographers such as Gemma Frisius, Gerardus Mercator and Abraham Ortelius

- Koeman, Cornelis; Schilder, Günter; van Egmond, M.; van der Krogt, Peter; Zandvliet, Kees: The History of Cartography, Volume 3: Cartography in the European Renaissance (Part 2: Low Countries), pp. 1246–1462, David Woodward ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007)

- that comprising mainland Australia, Tasmania and their surrounding islands

- The first European known to visit Sakhalin was Martin Gerritz de Vries, who mapped Cape Patience and Cape Aniva on the island's east coast in 1643. The Dutch captain, however, was not aware of their being on an island, and 17th century maps usually showed these points—and often Hokkaido, too—as parts of the mainland.

- McManamon, Francis; Cordell, Linda S.; Lightfoot, Kent; Milner, George (2009). Archaeology in America: An Encyclopedia (4 volumes), p. 26

- As Peter J. Taylor (2002) notes: 'The Dutch polity of the seventeenth century was famously unconcerned with territorial expansion: as long as the frontier operated effectively as a defensive shield no extra land was deemed necessary.'

- Knobel, E. B. (1917). "On Frederick de Houtman's Catalogue of Southern Stars, and the Origin of the Southern Constellations". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 77 (5): 414–432. Bibcode:1917MNRAS..77..414K. doi:10.1093/mnras/77.5.414. The constellations around the South Pole were not observable from north of the equator, by Babylonians, Greeks, Chinese or Arabs. During the Age of Exploration, expeditions to the southern hemisphere began to result in the addition of new constellations. The modern constellations in this region were defined notably by Dutch navigators Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser and Frederick de Houtman, who in 1595 traveled together to the East Indies (first Dutch expedition to Indonesia). These 12 newly Dutch-created southern constellations (that including Apus, Chamaeleon, Dorado, Grus, Hydrus, Indus, Musca, Pavo, Phoenix, Triangulum Australe, Tucana and Volans) first appeared on a 35-cm diameter celestial globe published in 1597/1598 in Amsterdam by Dutch cartographers Petrus Plancius and Jodocus Hondius. The first depiction of these constellations in a celestial atlas was in Johann Bayer's Uranometria of 1603.

- Simpson, Phil (2012): Guidebook to the Constellations: Telescopic Sights, Tales, and Myths, p. 559–561, p. 599–600

- Among 15 Dutch-created constellations (recognized by the IAU), three constellations including Camelopardalis, Columba, and Monoceros, formed by Petrus Plancius in 1592 and in 1613, are often erroneously attributed to Jacob Bartsch and Augustin Royer

- Swann, G. M. Peter (2006). Putting Econometrics in Its Place: A New Direction in Applied Economics, pp. 29–32

- Stachurski, Richard (2009). Longitude by Wire: Finding North America, p. 10

- Henzel, Cynthia Kennedy (2010). Creating Modern Maps, p. 6

- Bagrow, Leo (2010). History of Cartography, p. 159

- Hewitt, Rachel (2011). Map of a Nation: A Biography of the Ordnance Survey. "Triangulation had first emerged as a map-making method in the mid sixteenth century when the Flemish mathematician Gemma Frisius set out the idea in his Libellus de locorum describendorum ratione (Booklet concerning a way of describing places), and by the turn of the eighteenth century it had become the most respected surveying technique in use."

- Bellos, Alex (2014). The Grapes of Math: How Life Reflects Numbers and Numbers Reflect Life, p. 74

- Kirby, Richard Shelton et al. (1990). Engineering in History, p. 131

- Harwood, Jeremy (2006). To the Ends of the Earth: 100 Maps that Changed the World, p. 107

- Devreese, Jozef T.; Vanden Berghe, Guido (2009). Magic is No Magic: The Wonderful World of Simon Stevin, p. 272

- Struik, Dirk J. (1981). The Land of Stevin and Huygens: A Sketch of Science and Technology in the Dutch Republic during the Golden Century, p. 37

- Kirby, David; Hinkkanen, Merja-Liisa (2000). The Baltic and the North Seas, p. 61–62

- Buisseret, David (2003). The Mapmakers' Quest: Depicting New Worlds in Renaissance Europe

- Harwood, Jeremy (2006). To the Ends of the Earth: 100 Maps that Changed the World, p. 88

- Lasater, Brian (2007). The Dream of the West, Part II, p. 317

- Thrower, Norman J. W. (2008). Maps and Civilization: Cartography in Culture and Society, Third Edition, p. 84

- Kieding, Robert B. (2011). Scuttlebutt: Tales and Experiences of a Life at Sea, p. 290

- The 15 constellations are: Apus, Camelopardalis, Chamaeleon, Columba, Dorado, Grus, Hydrus, Indus, Monoceros, Musca, Pavo, Phoenix, Triangulum Australe, Tucana, and Volans.

- Knobel, E. B. (1917). On Frederick de Houtman's Catalogue of Southern Stars, and the Origin of the Southern Constellations. (Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Vol. 77, pp. 414–32)

- Sawyer Hogg, Helen (1951). "Out of Old Books (Pieter Dircksz Keijser, Delineator of the Southern Constellations)". Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. 45: 215. Bibcode:1951JRASC..45..215S.

- Dekker, Elly (1987). Early Explorations of the Southern Celestial Sky. (Annals of Science 44, pp. 439–70)

- Dekker, Elly (1987). On the Dispersal of Knowledge of the Southern Celestial Sky. (Der Globusfreund, 35–37, pp. 211–30)

- Verbunt, Frank; van Gent, Robert H. (2011). Early Star Catalogues of the Southern Sky: De Houtman, Kepler (Second and Third Classes), and Halley. (Astronomy & Astrophysics 530)

- Wood, Charles A. (27 December 2017). "Lunar Hall of Fame". Sky & Telescope (skyandtelescope.org). Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- "Library Item of the Month: Giovanni Riccioli's Almagestum novum". Royal Museums Greenwich (rmg.co.uk). 19 September 2016. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

Riccioli and Grimaldi's maps were not the first of the Moon. In 1645 Michael Van Langren published what is acknowledged as the first map of the Moon, introducing a scheme of names for its features, setting it apart from earlier unlabelled drawings of the Moon. Two years later, in 1647, Johannes Hevelius published maps of the Moon in his work Selenographia.

- Schilder, Günter (1993). A Continent Takes Shape: The Dutch Mapping of Australia, in Changing Coastlines, ed. M. Richards, & M. O'Connor, pp. 10–16. Canberra: National Library of Australia, 1993

- Zandvliet, Kees (1988). Golden Opportunities in Geopolitics: Cartography and the Dutch East India Company during the Lifetime of Abel Tasman, in Terra Australis: The Furthest Shore, ed. William Eisler and Bernard Smith, pp. 67–82. Sydney: International Cultural Corporation of Australia

- Schilder, Günter; Kok, Hans: Sailing for the East: History and Catalogue of Manuscript Charts on Vellum of the Dutch East India Company (VOC), 1602–1799. [Explokart: Utrecht Studies in the History of Cartography]. (BRILL, 2010, ISBN 9789061942603)

- Koeman, Cornelis; van Egmond, M.: Surveying and Official Mapping in the Low Countries, 1500–ca. 1670 (Part 2: Low Countries), pp. 1246–1295, David Woodward ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007)

- Schilder, Günter: Australia Unveiled: the Share of Dutch Navigators in the Discovery of Australia (includes bibliography). (Amsterdam: Thearum Orbis Terrarum, 1976)

- Schilder, Günter (1984) The Netherland Nautical Cartography from 1550 to 1650, RUC, Coimbra: BGUC, 1985, vol. XXXII, 97–119 (Lisboa: CEHCA)

- Schilder, Günter; van Egmond, M.: Maritime Cartography in the Low Countries during the Renaissance, (Part 2: Low Countries), pp. 1384–1432, David Woodward ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007)

- Schilder, Günter; Kok, Hans (2010). Sailing for the East: History and Catalogue of Manuscript Charts on Vellum of the Dutch East India Company (VOC), 1602–1799. BRILL. ISBN 9789061942603.

- Schilder, Günter (2017). Early Dutch Maritime Cartography: The North Holland School of Cartography (c. 1580 – c. 1620). BRILL. ISBN 9789004338029.

- Schmidt, Benjamin (1997), 'Mapping an Empire: Cartographic and Colonial Rivalry in Seventeenth-Century Dutch and English North America,'. The William and Mary Quarterly 54(3): 549–578

- Sutton, Elizabeth A. (2009), 'Mapping Meaning: Ethnography and Allegory in Netherlandish Cartography, 1570–1655,'. Itinerario 33(3): 12–42

- Sutton, Elizabeth A.: Early Modern Dutch Prints of Africa (Transculturalisms, 1400–1700). (Ashgate, 2012, 276 pp)

- Sutton, Elizabeth A.: Capitalism and Cartography in the Dutch Golden Age. (University of Chicago Press, 2015, 208 pp)

- Zandvliet, Kees: Mapping for Money: Maps, Plans and Topographic Paintings and their Role in Dutch Overseas Expansion During the 16th and 17th Centuries. (Batavian Lion International, 1998, 328 pp)

- Zandvliet, Kees: Mapping the Dutch World Overseas in the Seventeenth Century, (Part 2: Low Countries), pp. 1433–1462, David Woodward ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007)

Bibliography

Books, dissertations and theses:

- Ames, Glenn J.: The Globe Encompassed: The Age of European Discovery, 1500–1700. (Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2008)

- Binding, Paul: Imagined Corners: Exploring the World's First Atlas. (London: Headline Book Publishing, 2003)

- Bracht, J.Th.W. van (ed.): Atlas van kaarten en aanzichten van de VOC en WIC, genoemd Vingboons-Atlas, in het Algemeen Rijksarchief te 's-Gravenhage. (Haarlem: Fibula / Van Dishoeck, 1981) [in Dutch]

- Burnet, Ian: The Tasman Map, the Biography of a Map: Abel Tasman, the Dutch East India Company and the First Dutch Discoveries of Australia. (Sydney: Rosenberg Publishing, 2019)

- Carhart, George S.: Frederick de Wit and the First Concise Reference Atlas. (Leiden: Brill, 2016) ISBN 9789004299030

- Day, Alan: The A to Z of the Discovery and Exploration of Australia. (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2009) ISBN 978-0-8108-6810-6

- Deimann, Clemens: Maps in De Heere's Journal: Cartographic Reflections of VOC Policy on Ceylon, 1698. (MA thesis, Leiden University, 2018)

- Destombes, Marcel: Cartes hollandaises. La cartographie de la Compagnie des Indes Orientales, 1593–1743. La mappemonde de Petrus Plancius gravée par Josua van den Ende, 1604, d'après l'unique exemplaire de la Bibliothèque Nationale de Paris. (Saigon: C. Ardin, 1941) [in French]

- Gehring, Ulrike; Weibel, Peter (eds.): Mapping Spaces: Networks of Knowledge in 17th Century Landscape Painting. (Munich: Hirmer Verlag, 2015)

- Goffart, Walter: Historical Atlases: The First Three Hundred Years, 1570–1870. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003)

- Haddad, Thomás A. S.: Maps of the Moon: Lunar Cartography from the Seventeenth Century to the Space Age. (Boston / Leiden: Brill, 2020)

- Harwood, Jeremy: To the Ends of the Earth: 100 Maps That Changed the World. (Cincinnati, OH: F & W Publications, 2006)

- Jacobs, Elisabeth Maria: The Red-Haired in Japan: Dutch Influence on Japanese Cartography (1640–1853). (M.A. thesis, University of British Columbia, 1983)

- Karrow, Robert W.: Mapmakers of the Sixteenth Century and Their Maps: Bio-Bibliographies of the Cartographers of Abraham Ortelius, 1570 based on Leo Bagrow's A. Ortelii Catalogus Cartographorum. (Chicago: Speculum Orbis Press for the Newberry Library, 1993)

- Koeman, Cornelis: The History of Abraham Ortelius and his Theatrum Orbis Terrarum. (Lausanne: Sequoia, 1964)

- Meganck, Tine Luk: Erudite Eyes: Friendship, Art and Erudition in the Network of Abraham Ortelius (1527–1598) [Studies in Netherlandish Art and Cultural History, 14]. (Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2017)

- Monmonier, Mark: Rhumb Lines and Map Wars: A Social History of the Mercator Projection. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004)

- Nichols, Robert; Woods, Martin (eds.): Mapping Our World: Terra Incognita to Australia. (Canberra: National Library of Australia, 2013) ISBN 978-0-642-27809-8

- Paranavitana, K.D.; de Silva, R.K.: Maps and Plans of Dutch Ceylon: A Representative Collection of Cartography from the Dutch Period. (Colombo: Sri Lanka-Netherlands Association, 2002)

- Ryan, Simon: The Cartographic Eye: How Explorers Saw Australia. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996)

- Scharloo, Mieke; van Mil, Patrick (eds.): De VOC in de kaart gekeken: Cartografie en navigatie van de Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, 1602–1799. ('s-Gravenhage: SDU, 1988) [in Dutch]

- Schilder, Günter: Australia Unveiled: the Share of Dutch Navigators in the Discovery of Australia. Translated from the German by Olaf Richter. (Amsterdam: Thearum Orbis Terrarum, 1976)

- Schilder, Günter: In the Steps of Tasman and De Vlamingh. An Important Cartographic Document for the Discovery of Australia. (Amsterdam: Nico Israel, 1988)

- Schilder, Günter; Kok, Hans: Sailing for the East: History and Catalogue of Manuscript Charts on Vellum of the Dutch East India Company (VOC), 1602–1799. (Leiden: Brill, 2010)

- Schilder, Günter: Early Dutch Maritime Cartography: The North Holland School of Cartography (c. 1580 – c. 1620). (Leiden: Brill, 2017)

- Schmidt, Benjamin: Inventing Exoticism: Geography, Globalism, and Europe's Early Modern World. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015)

- Suárez, Thomas: Early Mapping of the Pacific: The Epic Story of Seafarers, Adventurers, and Cartographers Who Mapped the Earth's Greatest Ocean. (Singapore: Periplus Editions, 2004)

- Sutton, Elizabeth A.: Early Modern Dutch Prints of Africa. (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2012)

- Sutton, Elizabeth A.: Capitalism and Cartography in the Dutch Golden Age. (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2015) ISBN 978-0-226-25478-4

- Van den Boogaart, Ernst: Civil and Corrupt Asia: Image and Text in the Itinerario and the Icones of Jan Huygen van Linschoten. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003)

- Van den Broecke, Marcel; van der Krogt, Peter; Meurer, Peter (eds.): Abraham Ortelius and the First Atlas: Essays Commemorating the Quadricentennial of His Death, 1598–1998. ('t Goy-Houten: HES Publishers B.V., 1998)

- Van der Heijden, H.A.M.: Leo Belgicus: An Illustrated and Annotated Carto-Bibliography. (Alphen aan den Rijn: Canaletto, 1990)

- Van Mill, P.; Scharloo, M. (eds.): De VOC in de kaart gekeken: Cartografie en navigatie van de Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, 1602–1799 [Maps and Charts of the VOC: Cartography and Navigation of the Dutch East India Company, 1602–1799]. (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1988) [in Dutch]

- Whitaker, Ewen A.: Mapping and Naming the Moon: A History of Lunar Cartography and Nomenclature. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999)

- Woodfin, Thomas McCall: The Cartography of Capitalism: Cartographic Evidence for the Emergence of the Capitalist World-System in Early Modern Europe. (Ph.D. thesis, Texas A&M University, December 2007)

- Woodward, David (ed.): Art and Cartography: Six Historical Essays. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987)

- Zandvliet, Kees: Mapping for Money: Maps, Plans and Topographic Paintings and their Role in Dutch Overseas Expansion During the 16th and 17th Centuries. (Batavian Lion International, 1998)

Journal articles, scholarly papers, essays, and book chapters:

- Alpers, Svetlana (1987), 'The Mapping Impulse in Dutch Art,'; in Art and Cartography: Six Historical Essays, edited by David Woodward (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), p. 51–96

- De Meer, Sjoerd; Ormeling, Ferjan (2010), 'Het verhaal achter de Grote Atlas van de Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie: een interview met Rob van Diessen,' [The story behind the Comprehensive Atlas of the Dutch East India Company: an interview with Rob van Diessen]. Caert-Thresoor 29(3): 77–87. [in Dutch]

- Dekker, Elly (1987), 'Early Explorations of the Southern Celestial Sky,'. Annals of Science 44(5): 439–70

- Dekker, Elly (1987), 'On the Dispersal of Knowledge of the Southern Celestial Sky,'. Der Globusfreund 35–37: 211–30

- Kang, Peter (2018), 'The Dutch Commemorative Toponyms in the Seventeenth Century East Asia, Based on the Cartographic Works Left by the Dutch East India Company (VOC),'; in Mirela Altić, Imre Josef Demhardt & Soetkin Vervust (eds.), Dissemination of Cartographic Knowledge: 6th International Symposium of the ICA Commission on the History of Cartography, 2016. (Springer, 2018), pp. 257–267

- Kang, Peter (2019), 'Naming and Re-naming on Formosa: The Toponymic Legacies of the VOC Cartographies on the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Western Maps,'; in Martijn Storms, Mario Cams, Imre Josef Demhardt, Ferjan Oemeling (eds.), Mapping Asia: Cartographic Encounters Between East and West [Regional Symposium of the ICA Commission on the History of Cartography, 2017]. (Springer, 2019), pp. 95–109

- King, Robert J. (2016), 'From Beach to Western Australia: Dirk Hartog and the Transition from Speculative to Actual Geography,'. The Great Circle 38(1): 45–71

- Knobel, E. B. (1917), 'On Frederick de Houtman's Catalogue of Southern Stars, and the Origin of the Southern Constellations,'. (Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Vol. 77, pp. 414–32)

- Koeman, Cornelis (1972), 'The Lead by the Dutch in World Charting in the Seventeenth and First Half of the Eighteenth Century,'; in: Rutherford, W.H. (ed.), Second International Congress on the History of Oceanography: Challenger Expedition Centenary, Edinburgh, September 12 to 20, 1972, Proceedings 2, Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. Section B, Biological Sciences, 73: 45–49

- Koeman, Cornelis; van Egmond, M.: Surveying and Official Mapping in the Low Countries, 1500–ca. 1670 (Part 2: Low Countries), pp. 1246–1295, David Woodward ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007)

- Kozica, Kazimierz (2017), 'Different states of the sea chart of the Gulf of Riga by Lucas Janszoon Waghenaer (1534–1606) from his first sea atlas Spiegel der Zeevaert (1583/1585) in the Niewodniczański Collection Imago Poloniae at the Royal Castle in Warsaw,'. e-Perimetron 12(2): 75–83

- Livieratos, Evangelos; Koussoulakou, Alexandra (2006), 'Vermeer's Maps: a New Digital Look in an Old Master's Mirror,'. e-Perimetron 1(2): 138–154

- Paesie, Ruud (2010), 'Op perkament getekend: productie en omvang van het hydrografisch bedrijf van de VOC,' [Drawn on parchment: production and extent of the hydrographic business of the VOC]. Caert-Thresoor 29(1): pp. 1–8. [in Dutch]

- Ricci, Alessandro (2016), 'Maps, Power and National Identity. The Leo Belgicus as a Symbol of the Independence of the United Provinces,' ['Carte, potere e identità nazionale. Il Leo Belgicus come simbolo dell'indipendenza delle Province Unite,']. Bollettino dell'Associazione Italiana di Cartografia 154: 102–120. doi:10.13137/2282-472X/12113

- Saldanha, Arun (2011), 'The Itineraries of Geography: Jan Huygen van Linschoten's Itinerario and Dutch Expeditions to the Indian Ocean, 1594–1602,'. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 101(1): 149–177

- Sawyer Hogg, Helen (1951), 'Out of Old Books (Pieter Dircksz Keijser, Delineator of the Southern Constellations),'. Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada 45: 215

- Schilder, Günter (1976), 'Organisation and Evolution of the Dutch East India Company's Hydrographic Office in the Seventeenth Century,'. Imago Mundi 28: 61–78

- Schilder, Günter (1988), 'New Holland: The Dutch Discoveries,'; in Glyndwr Williams and Alan Frost (eds.), Terra Australis to Australia. (Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1988), pp. 83–115

- Schilder, Günter (1988), 'The So-Called "Atlas Amsterdam" by Isaak de Graaf of About 1700. A Remarkable Cartographic Document of the Dutch East India Company,'; in Vice-Almirante A. Teixeira da Mota: In Memoriam, vol. I, Lisboa: Academia de Marinha / IICT, 1988, pp. 133–154

- Schilder, Günter (1984), 'The Dutch Conception of New Holland in the Seventeenth and Early Eighteenth Centuries,'. The Globe: Journal of the Australian Map Circle 22: 38–46

- Schilder, Günter (1984), 'The Netherland Nautical Cartography from 1550 to 1650,'. RUC, Coimbra: BGUC, 1985, vol. XXXII: 97–119 (Lisboa: CEHCA)

- Schilder, Günter (1989), 'From Secret to Common Knowledge – The Dutch Discoveries,'; in John Hardy and Alan Frost (eds.), Studies from Terra Australis to Australia. (Canberra, 1989)

- Schilder, Günter (1993), 'A Continent Takes Shape: The Dutch mapping of Australia,'; in Changing Coastlines: Putting Australia on the World Map, 1493–1993, edited by Michael Richards & Maura O'Connor. (Canberra: National Library of Australia, 1993), pp. 10–16

- Schilder, Günter; van Egmond, M.: Maritime Cartography in the Low Countries during the Renaissance, (Part 2: Low Countries), pp. 1384–1432, David Woodward ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007)

- Schmidt, Benjamin (1997), 'Mapping an Empire: Cartographic and Colonial Rivalry in Seventeenth-Century Dutch and English North America,'. The William and Mary Quarterly 54(3): 549–578

- Sutton, Elizabeth A. (2009), 'Mapping Meaning: Ethnography and Allegory in Netherlandish Cartography, 1570–1655,'. Itinerario 33(3): 12–42

- Tunturi, Janne (2016), 'Cartographer's experience of time in the Mercator-Hondius Atlas (1606, 1613),'. Approaching Religion 6(1): 46–56. doi:10.30664/ar.67582

- Unger, Richard W. (2011), 'Dutch Nautical Sciences in the Golden Age: The Portuguese Influence,'. E-Journal of Portuguese History 9(2): 68–83

- Van der Krogt, Peter; Ormeling, Ferjan (2014), 'Michiel Florent van Langren and Lunar Naming,'. Els noms en la vida quotidiana. Actes del XXIV Congrés Internacional d'ICOS sobre Ciències Onomàstiques. Annex: 1851–1868. doi:10.2436/15.8040.01.190

- Verbunt, Frank; van Gent, Robert H. (2011), 'Early Star Catalogues of the Southern Sky: De Houtman, Kepler (Second and Third Classes), and Halley.'. Astronomy & Astrophysics 530. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201116795

- Welu, James A. (1975), 'Vermeer: His Cartographic Sources,'. The Art Bulletin 57(4): 529–547

- Welu, James A. (1987), 'The Sources and Development of Cartographic Ornamentation in the Netherlands,'; in Art and Cartography: Six Historical Essays, edited by David Woodward (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), p. 147–173

- Whitaker, Ewen A. (1999), 'Chapter 3: Van Langren (Langrenus) and the Birth of Selenography,'; in Ewen A. Whitaker, Mapping and Naming the Moon: A History of Lunar Cartography and Nomenclature. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999), pp. 37–47

- Zandvliet, Kees (1988), 'Golden Opportunities in Geopolitics: Cartography and the Dutch East India Company during the Lifetime of Abel Tasman,'; in Terra Australis: The Furthest Shore, ed. William Eisler and Bernard Smith (Sydney: International Cultural Corporation of Australia, 1988), pp. 67–82

- Zandvliet, Kees (1998), 'The Contribution of Cartography to the Creation of a Dutch Colony and a Chinese State in Taiwan,'. Cartographica: The International Journal for Geographic Information and Geovisualization 35(3–4): 123–135. doi:10.3138/C804-42RT-4047-W567