Aomori Prefecture

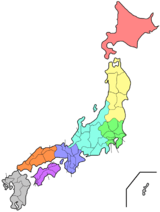

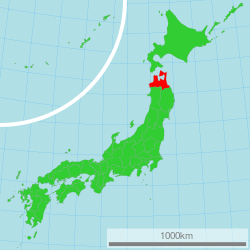

Aomori Prefecture (青森県, Aomori-ken) is a prefecture of Japan located in the Tōhoku region.[2] The prefecture's capital, largest city, and namesake is the city of Aomori.[3] The prefecture was made out of the northern part of the Mutsu Province during the Meiji Restoration. Aomori is the northernmost prefecture on Japan's main island, Honshu, and is bordered on the east by the Pacific Ocean, Iwate Prefecture to the southeast, Akita Prefecture to the southwest, the Sea of Japan to the west, and Hokkaido across the Tsugaru Strait to the north.

Aomori Prefecture 青森県 | |

|---|---|

| Japanese transcription(s) | |

| • Japanese | 青森県 |

| • Rōmaji | Aomori-ken |

Flag  Symbol | |

| |

| Country | Japan |

| Region | Tōhoku |

| Island | Honshu |

| Establishment as part of Mutsu Province | Around 1094 |

| Established as part of Rikuō Province | 7 December 1868 |

| Establishment of Aomori Prefecture | 4 September 1871 |

| Capital | Aomori |

| Subdivisions | Districts: 8, Municipalities: 40 |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Shingo Mimura |

| Area | |

| • Total | 9,645.64 km2 (3,724.20 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 8th |

| Highest elevation | 1,624.7 m (5,330 ft) |

| Lowest elevation (Pacific Ocean) | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population (June 1, 2019) | |

| • Total | 1,249,314 |

| • Rank | 31st |

| • Density | 130/km2 (340/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Aomorian |

| ISO 3166 code | JP-02 |

| Longitude | 139°30′ E to 141°41′ E |

| Latitude | 40°12′ N to 41°33′ N[1] |

| Website | www |

| Symbols of Aomori Prefecture | |

| Anthem | Hymn of Aomori Prefecture (青森県賛歌, Aomori-ken sanka) |

| Song | Message of the Blue Forest (青い森のメッセージ, Aoimori no messēji) |

| Bird | Bewick's swan (Cygnus bewickii) |

| Fish | Japanese halibut (Paralichthys olivaceus) |

| Flower | Apple blossom (Malus domestica) |

| Tree | Hiba (Thujopsis dolabrata) |

Aomori Prefecture is the 8th largest prefecture, with an area of 9,645.64 square kilometers (3,724.20 sq mi), and the 31st most populous prefecture, with more than 1.2 million people. Approximately 45 percent of Aomori Prefecture's residents live in its two core cities, Aomori and Hachinohe that lie on coastal plains. The majority of the prefecture is covered in forested mountain ranges, with population centers occupying valleys and plains. Aomori is the third most populous prefecture in the Tōhoku region, after Miyagi Prefecture and Fukushima Prefecture. Mount Iwaki, an active stratovolcano, is the prefecture's highest point, at almost 1,624.7 meters (5,330 feet).

Geography

Aomori Prefecture is the northernmost prefecture in the Tōhoku region, lying on the northern end of the island of Honshu. It faces Hokkaido from across the Tsugaru Strait. It borders Akita and Iwate in the south. The prefecture is flanked by the Pacific Ocean to the east and the Sea of Japan to the west with the Tsugaru Strait linking those bodies of water to the north of the prefecture. Oma, at the northwestern tip of the axe-shaped Shimokita Peninsula, is the northernmost point of Honshu. The Shimokita and Tsugaru Peninsulas enclose Mutsu Bay. Between those peninsulas lies the smaller Natsudomari Peninsula, the northern end of the Ōu Mountains. The three peninsulas are prominently visible in the prefecture's symbol, a stylized map.[4]

Lake Towada, a lake that sits in a volcanic caldera, straddles Aomori's boundary with Akita. The lakes is a primary feature of Towada-Hachimantai National Park. Within that park, the Oirase River flows east towards the Pacific Ocean from Lake Towada. Another feature of the park, the Hakkōda Mountains, an expansive volcanic group, rise in the lands to the south of the city of Aomori and north of Lake Towada.

The Shirakami Mountains are located in the western part of the prefecture and contain the last of the virgin beech tree forest which is home to over 87 species of birds. Mount Iwaki, a stratovolcano and the prefecture's highest point lies to northeast of the Shirakami Mountains. The lands to the east and northeast of Mount Iwaki are an expansive floodplain that is drained by the Iwaki River. Hirosaki, the former capital of the Tsugaru clan, sits on the banks of the river.[4]

As of 31 March 2019, 12% of the total land area of the prefecture was designated as Natural Parks, namely the Towada-Hachimantai and Sanriku Fukkō National Parks; Shimokita Hantō and Tsugaru Quasi-National Parks; and Asamushi-Natsudomari, Ashino Chishōgun, Iwaki Kōgen, Kuroishi Onsenkyō, Nakuidake, Ōwani Ikarigaseki Onsenkyō, and Tsugaru Shirakami Prefectural Natural Parks; and Mount Bonju Prefectural Forest.[5][6]

Cities

Towns and villages

City Town Village

These are the towns and villages in each district:

- Higashitsugaru District

- Hiranai

- Imabetsu

- Sotogahama

- Yomogita

- Kamikita District

- Kitatsugaru District

- Minamitsugaru District

- Nakatsugaru District

- Nishitsugaru District

- Sannohe District

- Shimokita District

- Higashidōri

- Kazamaura

- Ōma

- Sai

Mergers

Climate

The climate of Aomori Prefecture is relatively cool for the most part. It has four distinct seasons with an average temperature of 10 °C (50 °F). Variations in climate exist between the eastern (Pacific Ocean side) and the western (Sea of Japan side) parts of the prefecture. This is in part due to the Ōu Mountains that run north to south in the middle of the prefecture, dividing the two regions. The western side is subject to heavy monsoons and little sunshine which results in heavy snowfall during the winter. The eastern side is subject to low clouds brought in by northeasterly winds during the summer months, known locally as Yamase winds, from June through August, with temperatures staying relatively low. However, there are instances of Yamase winds making summers so cold that food production is hindered. The lowest recorded temperature during the winter is −9.3 °C (15.3 °F), and the highest recorded temperature during the summer is 33.1 °C (91.6 °F).[4][8]

History

Jōmon period

The oldest evidence of pottery in Japan was found at the Odai Yamamoto I site in the town of Sotogahama in the northwestern part of the prefecture. The relics found there suggest that the Jōmon period began about 15,000 years ago.[9] By 7,000 BCE fishing cultures had developed along the shores of the prefecture which were three meters higher than the present day shoreline.[10] Around 3,900 BCE settlement at the Sannai-Maruyama site in the present-day city of Aomori began.[11] The settlement shows evidence the wide interaction between the site's inhabitants and people from across Jōmon period Japan, including Hokkaido and Kyushu.[9] The settlement of Sannai-Maruyama ended around 2300 BCE due to unknown reasons. Its abandonment was likely due to the population's subsistence economy being unable to result in sustained growth, with its end being spurred on by the reduced amount of natural resources during the neoglaciation.[12] The Jōmon period continued up to 300 BCE in present-day Aomori Prefecture at the Kamegaoka site in the city of Tsugaru where the Shakōki-dogū was found.[9]

Yayoi period to Heian period

During the Yayoi period, the area that would become Aomori Prefecture was impacted by the migration of settlers from continental Asia to a lesser extent than the rest of Japan to the south and west of the region. The region, known then as Michinoku, was inhabited by the Emishi. It is not clear if the Emishi were the descendants of the Jōmon people, a group of the Ainu people, or if both the Ainu and Emishi were descended from the Jōmon people. The northernmost tribe of the Emishi that inhabited what would become Aomori Prefecture was known as the Tsugaru.[13] Historic records mention a series of destructive eruptions in 917 from the volcano at Lake Towada. The eruptive activity peaked on 17 August.[14] Throughout the Heian period the Emishi were slowly subdued by the Imperial Court in Kyoto before being incorporated into Mutsu Province by the Northern Fujiwara around 1094.[15] The Northern Fujiwara set up the port settlement Tosaminato in present-day Goshogawara to develop trade between their lands, Kyoto, and continental Asia.[16] The Northern Fujiwara were deposed in 1189 by Minamoto no Yoritomo who would go on to establish the Kamakura shogunate.[17]

Kamakura period

Minamoto no Yoritomo incorporated Mutsu Province into the holdings of the Kamakura shogunate. Nanbu Mitsuyuki was awarded vast estates in Nukanobu District after he had joined Minamoto no Yoritomo at the Battle of Ishibashiyama and the conquest of the Northern Fujiwara. Nanbu Mitsuyuki built Shōjujidate Castle in what is now Nanbu, Aomori.[18] The eastern area of the current prefecture was dominated by horse ranches, and the Nanbu grew powerful and wealthy on the supply of warhorses. These horse ranches were fortified stockades, numbered one through nine (Ichinohe through Kunohe), and were awarded to the six sons of Nanbu Mitsuyuki, forming the six main branches of the Nanbu clan.[19][20] The northwestern part of the prefecture was awarded to the Andō clan for their role in driving the Northern Fujiwara out of Tosaminato. The port was expanded under the rule of the Andō clan. They traded heavily with the Ainu in Ezo. However, conflict would break out between the Ainu and the Andō clan in 1268 and again in the 1320s. The conflict was put down after the Nanbu intervened at the behest of the shogunate. The conflict weakened the Kamakura shogunate in its later years, while the Andō were split into northern (Andō) and southern (Akita) divisions.[21]

Muromachi period

At the onset of Ashikaga shogunate the Nanbu and Andō continued to rule the area with the Nanbu controlling the current prefecture's southeastern section and the Andō controlling the Shimokita and Tsugaru peninsulas. The Andō also were involved with controlling the fringes of Ezo, splitting their attention. In 1336, the Andō completed construction of Horikoshi Castle during the Northern and Southern Courts period.[22] During the Muromachi, the Nanbu slowly began edging the Andō out of present-day Aomori Prefecture. The Andō were pushed out of Tosaminato in 1432, retreating to Ezo, giving the Nanbu control over all their lands. The port settlement would fall into disrepair under the Nanbu.[16]

Sengoku period

During the Sengoku period the Nanbu clan collapsed into several rival factions. One faction under Ōura Tamenobu asserted their control over the Hirosaki Domain. His clan, originally the Ōura clan (大浦氏, Ōura-shi), was of uncertain origins. According to later Tsugaru clan records, the clan was descended from the noble Fujiwara clan and had an accent claim to ownership of the Tsugaru region on the Tsugaru Peninsula and the area surrounding Mount Iwaki in the northwestern corner of Mutsu Province; however, according to the records of their rivals, the Nanbu clan, clan progenitor Ōura Tamenobu was born as either Nanbu Tamenobu or Kuji Tamenobu, from a minor branch house of the Nanbu and was driven from the clan due to discord with his elder brother.[23] In any event, the Ōura were hereditary vice-district magistrate (郡代補佐, gundai hosa) under the Nanbu clan's local magistrate Ishikawa Takanobu; however, in 1571 Tamenobu attacked and killed Ishikawa and began taking the Nanbu clan's castles in the Tsugaru region one after another.[24] He captured castles at Ishikawa, Daikoji and Aburakawa, and soon gathered support of many former Nanbu retainers in the region. After pledging fealty to Toyotomi Hideyoshi, he was confirmed as an independent warlord in 1590 and changed his name to "Tsugaru", formally establishing the Tsugaru clan. Tsugaru Tamenobu assisted Hideyoshi at the Battle of Odawara, and accompanied his retinue to Hizen during the Korean Expedition. Afterwards, he sided with Tokugawa Ieyasu during the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600.[25]

Edo period

After the establishment of the Tokugawa Shogunate the Nanbu ruled the Shimokita Peninsula and the districts immediately to the south of it. The area to the west of the Nanbu's holdings and to the north of the lands held by the Akita clan were all controlled by the Tsugaru clan from their capital at Hirosaki. Work on Hirosaki Castle was completed in 1611, replacing Horikoshi Castle as the Tsugaru clan's fortress.[22] By 1631, the Tsugaru clan had solidified their control over their gains made during the Sengoku period.[26] Mutsu Province was struck by the Great Tenmei famine between 1781 and 1789, due to lower than usual temperatures that were exacerbated by volcanic eruptions at Mount Iwaki, near the Tsugaru clan's capital, Hirosaki, between November 1782 and June 1783.[27]

At the beginning of the Edo period, the last pockets of Ainu people in Honshu still lived in the mountainous areas on the peninsulas of the prefecture. They interacted with the ruling clans to some extent, but they primarily lived off of fishing the waters of Mutsu Bay and the Tsugaru Strait. However, the Tsugaru clan made two big pushes to assimilate the Ainu, the first came in 1756 and the second came in 1809. Records show that the clan was successful in wiping out the Ainu culture in their holdings, though some geographic names in Aomori Prefecture still retain their original Ainu names.[28]

Meiji Restoration to World War II

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 475,413 | — |

| 1890 | 545,026 | +1.38% |

| 1903 | 665,691 | +1.55% |

| 1913 | 764,485 | +1.39% |

| 1920 | 756,454 | −0.15% |

| 1925 | 812,977 | +1.45% |

| 1930 | 879,914 | +1.60% |

| 1935 | 967,129 | +1.91% |

| 1940 | 1,000,509 | +0.68% |

| 1945 | 1,083,250 | +1.60% |

| 1950 | 1,282,867 | +3.44% |

| 1955 | 1,382,523 | +1.51% |

| 1960 | 1,426,606 | +0.63% |

| 1965 | 1,416,591 | −0.14% |

| 1970 | 1,427,520 | +0.15% |

| 1975 | 1,468,646 | +0.57% |

| 1980 | 1,523,907 | +0.74% |

| 1985 | 1,524,448 | +0.01% |

| 1990 | 1,482,873 | −0.55% |

| 1995 | 1,481,663 | −0.02% |

| 2000 | 1,475,728 | −0.08% |

| 2005 | 1,436,657 | −0.54% |

| 2010 | 1,373,339 | −0.90% |

| 2015 | 1,308,649 | −0.96% |

| source:[29] | ||

Despite the 1867 resignation of the last shogun, Tokugawa Yoshinobu, by late 1868 the Boshin War had reached in northern Japan. On 20 September 1868 the pro-Shōgunate Ōuetsu Reppan Dōmei was proclaimed at Morioka, the capital of the Nanbu clan who ruled Morioka Domain. The Tsugaru clan first sided with the pro-imperial forces of Satchō Alliance, and attacked nearby Shōnai Domain.[30][31] However, the Tsugaru soon switched course, and briefly became a member of the Ōuetsu Reppan Dōmei.[32] However, for reasons yet unclear, the Tsugaru backed out of the alliance and re-joined the imperial cause after a few months. The Nanbu and Tsugaru clans resumed their old rivalry and fought at the Battle of Noheji.[30]

As a result of the minor skirmish, the Tsugaru clan was able to prove its defection from the Ōuetsu Reppan Dōmei and loyalty to the imperial cause. Tsugaru forces later joined the imperial army in attacking the Republic of Ezo at the Battle of Hakodate, where the pro-Shōgunate forces were finally defeated.[33] As a result, the entire clan was able to evade the punitive measures taken by the Meiji government on other northern domains.[34]

In 1868 Mutsu Province was broken up into five provinces in the aftermath of the Boshin War, with its namesake province, Rikuō occupying what would later become Aomori Prefecture and the northwestern corner of Iwate Prefecture.[35] On 4 September 1871 Rikuō Province was abolished and divided, establishing today's Aomori Prefecture. Its capital was briefly located in Hirosaki, but it was moved on 23 September to the centrally located port village, Aomori.[36]

The prefecture's new capital, Aomori, saw rapid expansion was due to its importance as a logistic hub in northern Japan.[37] It became a town in 1889 and then a city in 1898. On 30 October 1889, an American merchant ship, the Cheseborough wrecked off the prefecture's west coast near the village Shariki, many of the ship's crew were saved by the villagers.[38] The Nippon Railway, a private company, completed the Tōhoku Main Line in 1891, linking Aomori to Ueno Station in Tokyo.[39] During a military exercise on 23 January 1902, 199 soldiers died after getting lost during a blizzard in the Hakkōda Mountains incident.[40] On 3 May 1910, a fire broke out in the Yasukata district. Fanned by strong winds, the fire quickly devastated the whole city. The conflagration claimed 26 lives and injured a further 160 residents. It destroyed 5,246 houses and burnt 19 storage sheds and 157 warehouses.

On 23 March 1945 a mudslide destroyed a section of the town of Ajigasawa, killing 87 of its inhabitants.[41] At 10:30 p.m. on 28 July 1945, a squadron of American B-29 bombers bombed over 90% of the city of Aomori. The estimated civilian impact of the air raid on the city was the death of 1,767 people and the destruction of 18,045 homes.[42] Infrastructure was destroyed across the prefecture including the Seikan Ferry, naval facilities in Mutsu and Misawa, Hachinohe Airfield, and the ports and railways of Aomori and Hachinohe.[43]

1945 to present

During the Occupation of Japan, Aomori's military bases were controlled by the US military. Hachinohe Airfield was occupied until 1950, and was called Camp Haugen.[44] Misawa Air Base was occupied and rebuilt by the United States Army Air Forces and the base has seen a US military presence since then.[45] Radio Aomori made its first broadcast in 1951. Four years later, the first fish auctions were held. 1958 saw the completion of the Municipal Fish Market as well as the opening of the Citizen's Hospital. In the same year, the Tsugaru Line established a rail connection with the village of Minmaya at the tip of the Tsugaru Peninsula.

Various outlying towns and villages were incorporated into the growing city of Aomori and with the absorption of the village of Nonai in 1962, Aomori became the largest city in the prefecture.

In March 1985, after 23 years of labor and a financial investment of 690 billion yen, the Seikan Tunnel finally linked the islands of Honshū and Hokkaidō, thereby becoming the longest tunnel of its kind in the world.[46] Almost exactly three years later, on March 13, railroad service was inaugurated on the Tsugaru Kaikyo Line. The tunnel's opening to rail traffic saw the end of the Seikan Ferry rail service. During their 80 years of service, the Seikan rail ferries sailed between Aomori and Hakodate some 720,000 times, carrying 160 million passengers. It continues to operate between the cities, ferrying automobile traffic and passengers rather than trains.

Aomori Public College opened in April 1993. In April 1995, Aomori Airport began offering regular international air service to Seoul, South Korea, and Khabarovsk, Russia; however, the flights to Khabarovsk were discontinued in 2004.[47]

In June 2007, four North Korean defectors reached Aomori Prefecture, after having been at sea for six days, marking the second known case ever where defectors have successfully reached Japan by boat.[48]

In March 2011, a magnitude 9.0 earthquake struck the east coast of Japan. The southeastern coast of Aomori Prefecture was affected by the resulting tsunami. Buildings along harbors were damaged along with boats thrown about in the streets.[49]

Demographics

A person living in or from Aomori Prefecture is referred to as an Aomorian.[50] As of 2017, the prefecture had a total population of 1.28 million residents. Accounting for just over 1 percent of Japan's total population.[51] In 2018, Aomori Prefecture saw the second largest decrease in the number of Japanese citizens out of any prefecture in the country. Only neighboring Akita Prefecture lost more citizens than Aomori.[52] In 2017, 23,529 people moved out of Aomori, while 17,454 people moved to the prefecture.[51] In 2018, about 590,000 of the prefecture's resident's were men and 670,000 were women, 10.8 percent of the population was below the age of 15, 56.6 percent of residents were between the ages of 15 and 64, and 32.6 percent was above the age of 64. In the same year the prefecture had a density of 130.9 people per square kilometer. In 2015, about 3,425 foreign-born immigrants lived in Aomori, making up just 0.0026 percent of the prefecture's population, the lowest of any prefecture.[53]

Economy

Like much of the Tōhoku Region, Aomori Prefecture remains dominated by primary sector industries such as farming, forestry, and fishing. In 2015, it's economy had a GDP of 4,541.2 billion yen which made up about 0.83 percent of Japan's economy.[51]

Aomori Prefecture generates the largest amount of wind energy, with large wind farms located on the Shimokita Peninusla. The peninsula is also home to the inactive Rokkasho Reprocessing Plant. The city of Hachinohe is home to the Pacific Metals Company, a manufacturer of ferronickel products.[4]

Agriculture

Aomori Prefecture is a leading agricultural region in Japan. It is Japan's largest producer of apples, accounting for 59 percent of Japan's total apple production in 2018.[54] The cultivation of apples in the prefecture began in 1875 when the prefecture was given three varieties of western origin to grow. The apples are consumed within Japan and exported to the United States, China, Taiwan, and Thailand.[4]

Aomori also boasts being the home to Hakkōda cattle, a rare, region-specific breed of Japanese Shorthorn.[55] The town of Gonohe has a long history as a breeding center for horses of exceptional quality, popular among the samurai. With the decline of the samurai, Gonohe's horses continued to be bred for their meat. The lean horse meat is coveted as a delicacy, especially when served in its raw form, known as Basashi (馬刺し). The Aomori coast along Mutsu Bay is a large source of scallops, but they are particularly a specialty of the town Hiranai where the calm water around Natsudomari Peninsula makes a good home for them.[56]

Aomori is also ranked highly in the nation's production of redcurrant, burdock, and garlic, accounting for 81, 37, and 66 percent, respectively, of the country's production.[54]

Tourism

Tourism has been a growing sector of Aomori Prefecture's economy. It was among the top five prefectures of Japan in terms of growth in foreign tourists between 2012 and 2017.[58] Major draws to the prefecture are its historic sites, museums, and national parks. About 35.2 million domestic travelers visited Aomori Prefecture in 2016, while about 95,000 foreign tourists visited in 2017.[51]

Military

As it sits on the northern end of Honshu, Aomori Prefecture occupies a strategic location to Japan and the United States. The Tsugaru Strait to the north of it serves as an access point for the United States Navy into the Sea of Japan where they can put pressure on Russia, China, and North Korea. host to the Misawa Air Base, the only combined, joint U.S. service installation in the western Pacific servicing Army, Navy, and Air Force, as well as the Japan Self-Defense Forces.[59] As such, it is host to Misawa Air Base, the only combined, joint U.S. service installation in the western Pacific servicing Army, Navy, and Air Force, as well as the Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF).[60] The JSDF maintains bases across the prefecture including, JMSDF Ōminato Base, JMSDF Hachinohe Air Base,[61] and JGSDF Camp Aomori.[62]

On 20 February 2018 a U.S. Air Force F-16 fighter jet caught fire in flight. The pilot dumped two fuel tanks into Lake Ogawara in eastern Aomori Prefecture.[63]

Culture

Traditional crafts

Aomori is well known for its tradition of Tsugaru-jamisen, a virtuosic style of shamisen playing. It is also where the decorative embroidery style, kogin-zashi, originated.[64]

Cuisine

The Aomori area has given rise to several soups: ke porridge which consists of miso soup with diced root vegetables and wild plants such as butterbur and bracken with tofu from the Tsugaru area; ichigoni, a sea urchin roe and abalone soup in which the sea urchin roe looks like strawberries, known as ichigo in Japanese, from the town of Hashikami; hittsumi a roux with chicken and vegetables from the Nanbu area; Hachinohe senbei soup a hearty soup with Nanbu senbei loaded with vegetables and chicken; jappa soup a vegetable soup with cod roe from Aomori; and keiran a red bean dumpling soy sauce soup served during special occasions on the Shimokita Peninsula.

Another dish that was created in the area surrounding Mutsu Bay is kaiya in the Tsugaru area or kayaki on the Shimokita Penninsula, it is a boiled miso and egg dish mixed with fish or scallop meat on a large scallop shell that serves as both the cookware and serveware.[65]

Festivals

Aomori Prefecture boasts a variety of festivals year round offering a unique look into northern Japan, and hosts the Aomori Nebuta Matsuri, one of the Three Great Festivals of Tōhoku.[66] During late April hanami festivals are held across the prefecture, with the most prominent of the festivals being located on the grounds of Hirosaki Castle.[67][68] Summer and autumn hold many distinct festivals with bright lights, floats, dancing and music.[69] Winter is centered on snow festivals where attendees can view ice sculptures and enjoy local cuisine inside an ice hut.[70]

|

|

Sports

Aomori Prefecture hosted the 2003 Asian Winter Games.[75] It is also slated to host the 80th National Sports Festival of Japan in 2025.[76]

Major professional teams

| Club | Sport | League | Stadium and city |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aomori Wat's | Basketball | B.League (East Second Division) | Maeda Arena, Aomori |

| ReinMeer Aomori | Association football | Japan Professional Football League (JFL) | Maeda Arena, Aomori |

| Tohoku Free Blades | Ice hockey | Asia League Ice Hockey | Flat Arena, Hachinohe |

| Vanraure Hachinohe | Association football | Japan Professional Football League (J3 League) | Prifoods Stadium, Hachinohe |

Minor professional and amateur teams

| Club | Sport | League | Stadium and city |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blancdieu Hirosaki FC | Association football | Tohoku Soccer League (Division 1) | Hirosaki Sports Park, Hirosaki |

| Hachinohe Reds | Ice hockey | Japan Women's Ice Hockey League | Tanabu Ice Hockey Arena, Hachinohe |

| Hirosaki Areds | Baseball | Japan Amateur Baseball Association | Hirosaki |

| King Blizzard | Baseball | Japan Amateur Baseball Association | Goshogawara |

Other teams

The Aomori Curling Club was a curling club of the Japan Curling Association from the city of Aomori that represented Japan in the 2006 Winter Olympics and the 2010 Winter Olympics and several World Curling Championships. The club was disbanded in 2013.[77]

Transportation

Airports

There are two airports located within the Aomori Prefecture. Both airports are relatively small, though Aomori Airport offers regular international flights to South Korea and Taiwan, seasonal flights to China, and chartered flights to Thailand, in addition to domestic flights.[78]

Railway

Stations

The following major stations are located in Aomori Prefecture.

Lines

The following lines, operated by East Japan Railway Company (JR East), run through Aomori Prefecture.

Road

Expressways

National highways

Education

Universities

- Aomori Chuo Gakuin University

- Aomori Public University

- Aomori University

- Aomori University of Health and Welfare

- Hachinohe Gakuin University

- Hachinohe Institute of Technology

- Hirosaki Gakuin University

- Hirosaki University

- Hirosaki University of Health and Welfare

- Tohoku Women's College

- Kitasato University (Towada Campus)

Symbols and names

.jpg)

A main-belt asteroid that was discovered by the Lowell Observatory Near-Earth-Object Search, 19701 Aomori, is named after Aomori Prefecture. The asteroid was given the name on 9 May 2012 after the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami to pay respect towards the damaged communities along the prefecture's southeastern coast.[79]

Prefectural symbols

Since 1961, the prefectural symbol of Aomori is a green stylized map of the prefecture on a white background, showing the crown of Honshū: the Tsugaru, Natsudomari and Shimokita Peninsulas. The green is representative of development while the white symbolizes the vastness of the world.[80]

The prefectural bird has been Bewick's swan since 1964, the species migrates to the area during the winter. In 1966, the prefecture designated the hiba (Thujopsis dolabrata) as its prefectural tree. The apple blossom was designated as the prefectural flower in 1971 to pay homage to the prefecture's apple production. In 1987, the Japanese halibut was designated as the prefectural fish.[80]

Dialects

According to Ken Cannon, there are three major dialects spoken in Japan; standard Japanese, Kansai dialect and Tōhoku dialect. Tōhoku dialect, or Tōhoku-ben, is found in northern Japan and is spoken between farmers and country folks. This dialect is also referred to as "zuu zuu-ben" because its phonology causes the Standard Japanese syllables /(d)zɯ, (d)ʑi/, as well as, intervocally, /tsɯ, tɕi, sɯ, ɕi/ to merge into /zɯ/. There is a negative connotation that surrounds people that speak this dialect, labeling them as lazy country folks. Due to this negativity speakers of Tōhoku-ben will often hide their accents.[81]

There are dozens of versions of this Tōhoku-ben, with two notably major ones in found in the Aomori Prefecture; Tsugaru-ben (津軽弁) and Nanbu-ben (南部弁). The former is prevalent in the area around Hirosaki, and the latter is heard in and around Hachinohe. According to a study done by Hideki Tanaka, the "dz" and "s" consonants undergo palatalization in the Nambu dialect. There is also the dialect Shimokita-ben (下北弁), which was used in the early Russian–Japanese Dictionary made by a Japanese Russian man whose father came from the Shimokita Peninsula. It is a combination of Tsugaru-ben and Nanbu-ben.[82]

Media

The largest newspaper by readership is The Tōō Nippō Press with a daily readership of 245,000, 56% of the total share of the newspaper market in the prefecture.[83]

Notable people from Aomori Prefecture

- Osamu Dazai, author

- Miki Hanada, nurse

- Miki Furukawa, musician, and former bass guitarist and singer for the Japanese rock band Supercar

- Junji Ishiwatari, musician, and former guitarist and songwriter for the Japanese rock band Supercar

- Daimaou Kosaka, comedian

- Kenichi Matsuyama, actor

- Daisuke Matsuzaka, Major League Baseball pitcher[84]

- Hani Motoko, journalist

- Koji Nakamura, musician, and former guitarist and lead singer for the Japanese rock band Supercar

- Yoshie Shiratori, escape artist

- Daigo Umehara, fighting game player, one of the most successful Street Fighter players

- Yoshisada Yonezuka, martial arts instructor

- Yokoyama Yui, Aomori Representative for AKB48 Team 8

Notes

- "場所・気候" [Place and climate] (in Japanese). Aomori Prefefcture Government. 20 May 2020. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005). "Aomori-ken" in Japan Encyclopedia, p. 35, p. 35, at Google Books; "Tōhoku" in p. 970, p. 970, at Google Books

- Nussbaum, "Aomori" in p. 35, p. 35, at Google Books

- Takaaki Nihei (2018). The Regional Geography of Japan. Sapporo: The Hokkaido University Press. pp. 13–19. ISBN 978-4-8329-0373-9.

- 自然公園都道府県別面積総括 [General overview of area figures for Natural Parks by prefecture] (PDF) (in Japanese). Ministry of the Environment. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- 青森県内の自然公園 [Natural Parks in Aomori Prefecture] (in Japanese). Aomori Prefecture. 31 March 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- "Aomori (Japan): Prefecture, Cities, Towns and Villages - Population Statistics, Charts and Map". www.citypopulation.de. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- Hiroshi Takai (2006). "Characteristics of the Yamase Winds over Oceans around Japan Observed by the Scatterometer-Derived Ocean Surface Vector Winds". Journal of the Meteorological Society of Japan. pp. 365–373. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- "Historic Site, Odai-Yamamoto Site" (PDF). Jomon Archaeological Sites in Hokkaido and Northern Tohoku. 2019. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- "Choshichiyachi Shell Midden". Jomon Archaeological Sites in Hokkaido and Northern Tohoku. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- Junko Habu (September 2008). "Growth and decline in complex hunter-gatherer societies: a case study from the Jomon period Sannai Maruyama site, Japan" (PDF). Antiquity. Cambridge University Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-12-25. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- Junko Habu; Mark Hall (1 December 2013). Climate Change, Human Impacts on the Landscape, and Subsistence Specialization: Historical Ecology and Changes in Jomon Hunter-Gatherer Lifeways. The Archaeology and Historical Ecology of Small Scale Economies. University of California, Berkeley. ISBN 9780813042428. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- Kazuro Hanihara (1990). "Emishi, Ezo and Ainu: An Anthropological Perspective". Japan Review (1): 35–48. JSTOR 25790886.

- "十和田" [Towada] (in Japanese). Japan Meteorological Agency. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- Mark J. Hudson (1999). "Ainu Ethnogenesis and the Northern Fujiwara". Arctic Anthropology. 36 (1/2): 73–83. JSTOR 40316506.

- "十三湊遺跡" [Ruins of Tosaminato]. The Agency for Cultural Affairs (in Japanese). Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- "History of Hiraizumi". Hiraizumi, Pure Land's World. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- "聖寿寺館跡" [Shōjojidate ruins]. Cultural Heritage Online (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- "伝説・地名" [Legends and place names] (in Japanese). Aomori Prefecture Government. 20 May 2020. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- "第2次五戸町総合振興計画" [Second Gonohe Town Promotion Plan] (PDF). Gonohe Town Promotion Plan. Gonohe Town. November 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 January 2018. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- "陸奥・福島城(青森県・十三湊)の見どころと安藤氏の乱" [Mutsu and Fukushima Castle (Aomori Prefecture, Tosaminato) highlights and the Andō Rebellion] (in Japanese). Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- "津軽氏城跡" [Tsugaru Castle ruins]. Hirosaki City. 2014. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- Ravina, Mark (1999). Land and Lordship in Early Modern Japan. Stanford University Press. p. 117. ISBN 0804728984.

- (in Japanese) "Tokugawa Bakufu to Tozama 117 han." Rekishi Dokuhon. April 1976 (Tokyo: n.p., 1976), p. 71.

- Edwin McClellan (1985). Woman in the Crested Kimono (New Haven: Yale University Press), p. 164.

- "弘前公園の歴史" [History of Hirosaki Park]. Hirosaki Park (in Japanese). Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- "「命を救った食べ物~飢饉の歴史と生きるための食物~」" [Food that saves life, the history of food production during famines]. Iwate Prefecture Government. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- "アイヌ語と津軽半島" [Ainu language and the Tsugaru Peninsula] (in Japanese). 24 November 2014. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- Statistics Bureau of Japan

- McClellan, p. 175.

- Mark Ravina (1999), Land and Lordship in Early Modern Japan (California: Stanford University Press), pp. 152-153.

- Onodera, p. 140.

- Koyasu, Buke kazoku meiyoden vol. 1, p. 6.

- Ravina, p. 153.

- "地名「三陸地方」の起源に関する地理学的ならびに社会学的問題" [Geographical and sociological issues concerning the origin of the place name "Sanriku region"] (PDF) (in Japanese). 30 June 1994. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- "青森県史の質問箱03" [Aomori Prefecture History Question Box 03]. Aomori Prefecture Government (in Japanese). 27 August 2008. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- "年表で見る青森県の歴史" [Timeline of Aomori Prefecture]. Aomori Prefecture Government (in Japanese). 24 June 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- "WRECKED OFF THE JAPAN COAST. NINETEEN OF THE CREW OF AN AMERICAN SHIP LOST". The New York Times. New York: NYTC. 7 November 1889. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- Free, Early Japanese Railways 1853–1914: Engineering Triumphs That Transformed Meiji-era Japan, Tuttle Publishing, 2008 (ISBN 4805310065)

- Nitta, Jirō (September 2007). Death March on Mount Hakkōda. Stone Bridge Press. ISBN 978-1933330327.

- "赤石村雪泥流災害" [Akaishi Village snow mudflow disaster]. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- "青森空襲" [Aomori Air Raid] (in Japanese). 24 November 2008. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- "米戦艦機による空襲=115" [US battleship air raid 115]. Mutsu Shinpō (in Japanese). 8 July 2019. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- "U.S. ARMY IN JAPAN 1945~" (PDF). June 2018. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- "Misawa Air Force Base in Misawa, Japan". Military Bases.com. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- "30 years on, world's longest undersea tunnel faces challenges as Japan balances bullet trains with freight". The Japan Times. 14 March 2018. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- Aomori City Homepage - The Story of Aomori. Retrieved on 7 June 2007 Archived May 22, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- "4 North Korean defectors reach Japan after 6 days on the open sea" Archived 2014-02-02 at the Wayback Machine Japan News Review (3 June 2007). Retrieved on 19 July 2008

- "The area is searched". Earthquake Memorial Museum. Tohoku Regional Bureau, Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- Nanette Gottlieb (2012). Language in Public Spaces in Japan. Routledge. p. 96. ISBN 978-0415818391. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- "ECONOMIC OVERVIEW OF TOHOKU REGION" (PDF). Tohoku Bureau of Economy, Trade and Industry. 2018. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- Jiji (10 July 2019). "Japan's population continues to slide even as foreign resident numbers increase". The Japan Times. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- "System of Social and Demographic Statistic". Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. 21 February 2020. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- "世界一と日本一" [The Best in the World and Japan] (in Japanese). Aomori Prefecture Government. 20 May 2020. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- Aomori City Homepage - The Story of Aomori. Retrieved on 7 June 2007 Archived May 22, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- 青森県平内町. "水産業 - 青森県平内町". town.hiranai.aomori.jp. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- "Oirase Gorge". Aomori Prefecture, Tourism and International Affairs Strategy Bureau. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- "Japan's tourism boom is spreading economic benefits to rural areas: report". 5 June 2018. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- "Japan left key straits open for U.S. nukes". The Japan Times. 22 June 2009. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- "Welcome to Naval Air Facility Misawa". US Navy. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- "Japan Maritime Self Defence Force Nihon Kaijyo Jieitai". Federation of American Scientists. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- "第9師団" [9th Division] (in Japanese). Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- "UPDATE: U.S. fighter dumps fuel tanks during flight after engine fire". The Asahi Shimbun. Archived from the original on 19 February 2019. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- "Kogin-zashi Embroidery". Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- "青森県の文化(郷土料理)" [Culture of Aomori Prefecture (local cuisine)] (in Japanese). Aomori Prefecture Government. 1 July 2012. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- "東北三大祭り中止/雌伏の時を経て来年こそ" [Cancellation of the Three Great Festivals of Tōhoku, next year's fate is undecided]. Kahoku Shimpō (in Japanese). 16 April 2020. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- "HANAMI (CHERRY BLOSSOM VIEWING)". JTB Corporation. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- "Visit Hirosaki in Aomori Prefecture, one of the best spots for cherry blossoms in Japan". Japan National Tourism Organization. January 2015. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- "Aomori's festivals make the short summer of northland more excited". APTINET AOMORI Prefectural Government. 19 July 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- "Winter Festival in Aomori, 2016". APTINET AOMORI Prefectural Government. 12 January 2016. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- "Festivals and Fireworks : Aomori Prefecture". Northern-Tohoku. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013.

- "Tachi Neputa Festival in Goshogawara City". Aomorimori.wordpress.com. 15 September 2009. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- "Fall Festivals : Aomori Prefecture". Northern-Tohoku. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013.

- "Lake Towada Winter Festival". MisawaJapan.com. Retrieved 6 August 2009.

- "History of Asian Games". Inside the Games. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- "第80回国民スポーツ大会" [80th National Sports Festival] (in Japanese). Aomori Prefecture Government. 2 July 2020. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- "チーム青森を応援していただいた皆様へを掲載" [To everyone who supported Team Aomori] (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 2 March 2013. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- "出発便:青森空港発" [Departures from Aomori Airport]. Aomori Airport (in Japanese). Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- "19701 Aomori (1999 SH19)". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- "シンボル" [Symbol] (in Japanese). 20 May 2020. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- "All You Need to Know About Japan's Weirdest Dialect, Tohoku-ben". Tofugu. 25 July 2011. Archived from the original on 7 November 2011.

- "Web東奥・天地人20110201" (in Japanese). Toonippo. February 1, 2011. Archived from the original on 20 March 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- "Company listing". The Tōō Nippō Press. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- "Matsuzaka". nikkansports.com. Archived from the original on 2008-06-09. Retrieved 2008-05-23.

References

- Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric and Käthe Roth. (2005). Japan encyclopedia. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01753-5; OCLC 58053128

- Tanaka, Hideki (1996-09-10). "On the Palatalization of [dz] and [s] in the Nambu Dialect" (PDF). Tsukuba English Studies. 15: 159–186.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aomori prefecture. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Aomori prefecture. |

- Aomori Prefecture Official Website (in Japanese)

- Aomori Prefecture Official Website (in English)