Abortion in Illinois

Abortion in Illinois is legal. Laws about abortion dated to the early 1800s in Illinois, and it became a criminal offense for the first time in 1827. Illegal abortions date in the state date back to 1888. As hospitals set up barriers in the 1950s, the number of therapeutic abortions declined. Following Roe v. Wade in 1973, Illinois updated its existing abortion laws in late May 2019. By 2010, the state had a number of newer abortion limitations in place including Targeted Regulation of Abortion Providers (TRAP). The state has seen a decline in abortion clinics over the years, going from 58 in 1982 to 47 in 1992 to 24 in 2014.

A 2014 poll of people in Illinois in 2014 found 56% believed that abortion should be legal in all or most cases. That same year, 38,472 abortion procedures took place in the state, 8.2% by out of state residents. Publicly funded abortions for poor women came from a mix of state and federal resources. Abortion rights activism has been present in the state for many years, with Abortion Counseling Service of the Chicago Women's Liberation Union created in the early 1960s, helping around 12,000 women get abortions between 1969 and 1973. Protests have also taken place, including a #StoptheBans march in Chicago in May 2019. Several anti-abortion rights organizations are also based in Illinois, including Illinois Family Institute (IFI) and the Eagle Trust Fund founded by Phyllis Schlafly. Illinois has also seen anti-abortion rights violence, including a bombing in 1982, a kidnapping in August 1982, and a priest driving a car into a clinic in September 2000. All state statues placing some restrictions on abortion were later repealed in June 2019.[1][2]

Terminology

The abortion debate most commonly relates to the "induced abortion" of an embryo or fetus at some point in a pregnancy, which is also how the term is used in a legal sense.[note 1] Some also use the term "elective abortion", which is used in relation to a claim to an unrestricted right of a woman to an abortion, whether or not she chooses to have one. The term elective abortion or voluntary abortion describes the interruption of pregnancy before viability at the request of the woman, but not for medical reasons.[3]

Anti-abortion advocates tend to use terms such as "unborn baby", "unborn child", or "pre-born child",[4][5] and see the medical terms "embryo", "zygote", and "fetus" as dehumanizing.[6][7] Both "pro-choice" and "pro-life" are examples of terms labeled as political framing: they are terms which purposely try to define their philosophies in the best possible light, while by definition attempting to describe their opposition in the worst possible light. "Pro-choice" implies that the alternative viewpoint is "anti-choice", while "pro-life" implies the alternative viewpoint is "pro-death" or "anti-life".[8] The Associated Press encourages journalists to use the terms "abortion rights" and "anti-abortion".[9]

Context

Free birth control correlates to teenage girls having a fewer pregnancies and fewer abortions. A 2014 New England Journal of Medicine study found such a link. At the same time, a 2011 study by Center for Reproductive Rights and Ibis Reproductive Health also found that states with more abortion restrictions have higher rates of maternal death, higher rates of uninsured pregnant women, higher rates of infant and child deaths, higher rates of teen drug and alcohol abuse, and lower rates of cancer screening.[10]

According to a 2017 report from the Center for Reproductive Rights and Ibis Reproductive Health, states that tried to pass additional constraints on a women's ability to access legal abortions had fewer policies supporting women's health, maternal health and children's health. These states also tended to resist expanding Medicaid, family leave, medical leave, and sex education in public schools.[11] According to Megan Donovan, a senior policy manager at the Guttmacher Institute, states have legislation seeking to protect a woman's right to access abortion services have the lowest rates of infant mortality in the United States.[11]

Poor women in the United States had problems paying for menstrual pads and tampons in 2018 and 2019. Almost two-third of American women could not pay for them. These were not available through the federal Women, Infants, and Children Program (WIC).[12] Lack of menstrual supplies has an economic impact on poor women. A study in St. Louis found that 36% had to miss days of work because they lacked adequate menstrual hygiene supplies during their period. This was on top of the fact that many had other menstrual issues including bleeding, cramps and other menstrual induced health issues.[12] Connecticut, Florida, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, Nevada, and Pennsylvania all had exemptions for essential hygiene products like tampons and menstrual pads as of November 2018.[13][14][15][16]

History

The Chicago Times published an undercover exposé on abortion in the city in 1888. One reporter managed to get a referral for an abortion with the head of the Chicago Medical Society.[17] In 1956, Mt. Sinai Hospital in Chicago created an anonymous committee to approve all requests for therapeutic abortions. As a result, the number of therapeutic abortions in 1957 was 3, down from 15 the previous year.[18]

Legislative history

A law in Illinois from the early 1800s prohibited the sale of drugs that could induce abortions. The law classed these as a poison.[19] In 1827, Illinois became the first state in the national to criminalize by statute abortion before prequickening.[20] Illinois passed a bill making abortion a criminal offense in early 1867.[21] Around 1870, Illinois passed another law banning the sale of drugs that could cause induced abortions. The law is notable because it allowed an exception for "the written prescription of some well known and respectable practicing physician." [19] In the 19th century, bans by state legislatures on abortion were about protecting the life of the mother given the number of deaths caused by abortions; state governments saw themselves as looking out for the lives of their citizens.[20]

In 2013, state Targeted Regulation of Abortion Providers (TRAP) law applied to private doctor offices in addition to abortion clinics.[22]

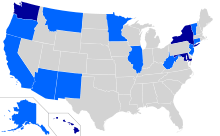

As of 2017, Washington State, New Mexico, Illinois, Alaska, Maryland, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Jersey allow qualified non-physicians to prescribe drugs for medical abortions only.[23]

Prior to May 2019, state law had not been updated since Roe v. Wade and officially banned abortions after 12 weeks.[24] In February 2019, state legislators had introduced a bill to make abortion a person's right to have and remove the 12 week ban from the books.[24][25] Action was demanded in May 2019 to try to move this bill ahead after Alabama and Georgia's state governments passed laws all but restricting abortions.[24][26] As of May 14, 2019, the state prohibited abortions after the fetus was viable, generally some point between week 24 and 28 based on the standard defined by the US Supreme Court in 1973 with the Roe v. Wade ruling, not because of legislative action.[27][24][25]

On May 31, 2019, the Illinois General Assembly became the eleventh state to pass bills protecting abortion rights in the state in response to anti-abortion legislation being passed elsewhere. The bills, pushed through by the Democratic controlled House and Senate and known as the Reproductive Health Act, provide statutory protections for abortions and rescinded previous legislation that banned some late-term abortions and a 45-year-old law that had made performing such abortions a criminal offense. After the bill passed, Governor Pritzker was on the Illinois Senate floor, hugging and congratulating abortion rights supporters.[28][29][30] The Reproductive Health Act said, women have the "fundamental right" to access abortion services and that a "fertilized egg, embryo, or fetus does not have independent rights."[31] Pritzker signed the bill into law on June 12, 2019[1][2]

Judicial history

The US Supreme Court's decision in 1973's Roe v. Wade ruling meant the state could no longer regulate abortion in the first trimester.[20]

Clinic history

Between 1982 and 1992, the number of abortion clinics in the state decreased by 11, going from 58 in 1982 to 47 in 1992.[32] In 2014, there were 24 abortion clinics in the state.[33] 92% of the counties in the state did not have an abortion clinic. That year, 40% of women in the state aged 15 – 44 lived in a county without an abortion clinic.[34] In 2017, there were 17 Planned Parenthood clinics in a state with a population of 3,003,374 women aged 15 – 49 of which 11 offered abortion services.[35] Following the announcement in late-May 2019 that the last remaining abortion clinic in the state of Missouri would likely close because it was unable to meet new state licensing rules, abortion clinics in Illinois prepared for an influx of new patients by hiring additional staff and increasing their opening hours. Hope Clinic in Granite City was one of the clinics most likely to be impacted because of its location relative to St. Louis, Missouri.[36][37]

Statistics

In the period between 1972 and 1974, the state had an illegal abortion mortality rate per million women aged 15 – 44 of between 0.1 and 0.9.[38] In 1990, 1,402,000 women in the state faced the risk of an unintended pregnancy.[32] In 2014, 56% of adults said in a poll by the Pew Research Center that abortion should be legal in all or most cases.[39] In 2017, the state had an infant mortality rate of 6.1 deaths per 1,000 live births.[11]

| Census division and state | Number | Rate | % change 1992–1996 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1992 | 1995 | 1996 | 1992 | 1995 | 1996 | ||

| East North Central | 204,810 | 185,800 | 190,050 | 20.7 | 18.9 | 19.3 | –7 |

| Illinois | 68,420 | 68,160 | 69,390 | 25.4 | 25.6 | 26.1 | 3 |

| Indiana | 15,840 | 14,030 | 14,850 | 12 | 10.6 | 11.2 | –7 |

| Michigan | 55,580 | 49,370 | 48,780 | 25.2 | 22.6 | 22.3 | –11 |

| Ohio | 49,520 | 40,940 | 42,870 | 19.5 | 16.2 | 17 | –13 |

| Wisconsin | 15,450 | 13,300 | 14,160 | 13.6 | 11.6 | 12.3 | –9 |

| Location | Residence | Occurrence | % obtained by

out-of-state residents |

Year | Ref | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Rate^ | Ratio^^ | No. | Rate^ | Ratio^^ | ||||

| Illinois | 68,420 | 25.4 | 1992 | [40] | |||||

| Illinois | 68,160 | 25.6 | 1995 | [40] | |||||

| Illinois | 69,390 | 26.1 | 1996 | [40] | |||||

| Illinois | 33,918 | 13.1 | 214 | 38,472 | 14.8 | 243 | 8.2 | 2014 | [41] |

| Illinois | 35,237 | 13.7 | 223 | 39,856 | 15.5 | 252 | 8.5 | 2015 | [42] |

| Illinois | 33,311 | 13.1 | 216 | 38,382 | 15.1 | 249 | 12.2 | 2016 | [43] |

| ^number of abortions per 1,000 women aged 15–44; ^^number of abortions per 1,000 live births | |||||||||

Abortion financing

17 states including Illinois used their own funds to cover all or most "medically necessary" abortions sought by low-income women under Medicaid, 13 of which are required by State court orders to do so.[44] In 2010, the state had 371 publicly funded abortions, of which were 237 federally and 134 were state funded.[45]

Criminal prosecution

Between 1974 and May 2019, there was a law that said that anyone who performed a late term abortion could be charged criminally with that offense. No one was ever charged with violating that law.[28]

Abortion rights activism

Organizations

The Abortion Counseling Service of the Chicago Women's Liberation Union was established by Chicago area feminists as a way to try to provide local women with safe and affordable illegal abortions during the late 1960s and early 1970s. According to Laura Kaplan who wrote a history of the group, members assisted women in having 11,000 safe abortions.[46][47] Another estimate put the total abortions assisted by the group as 12,000 between 1969 and 1973.[47]

Activities

.jpg)

Webster v. Reproductive Health Services was before the US Supreme Court in 1989. The Court ruled in a case over a Missouri law that banned abortions being performed in public buildings unless there was a need to save the life of the mother, required physicians to determine if a fetus was past 20 weeks and was viable in addition to other restrictions on a woman's ability to get an abortion. The US Supreme Court largely ruled in favor of the law, but made clear that this was not an overruling of Roe v. Wade.[48] As a response to this Supreme Court decision, the radical feminist art collective Sister Serpents was formed in Chicago to empower women and to increase awareness of women's issues through radical art.[49][50]

Protests

Women from the state participated in marches supporting abortion rights as part of a #StoptheBans movement in May 2019.[51] Many women wore red, referencing women in Margaret Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale in Chicago.[52]

Views

Women in Film Executive Director Kirsten Schaffer said of Georgia and other states similar restrictive abortion bans passed in early 2019, “A woman’s right to make choices about her own body is fundamental to her personal and professional well-being. [...] We support people who make the choice not to take their production to Georgia or take a job in Georgia because of the draconian anti-choice law. To that end, we’ve compiled a list of pro-choice states that offer meaningful tax rebates and production incentives, and encourage everyone to explore these alternatives: California, Colorado, Hawaii, Illinois, Maine, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Washington.”[53]

Anti-abortion activities and views

Organizations

Illinois Family Institute (IFI), a Christian nonprofit organization opposed to abortion, separation of church and state, "activist judges", the "marriage penalty", civil unions, same-sex marriage, gambling and drug legalization based in Illinois.[54][55][56]

In 1967, Phyllis Schlafly launched the Eagle Trust Fund in Chicago, Illinois for receiving donations related to conservative causes.[57] The Eagle Forum was pegged by Schlafly as "the alternative to women's lib." It is opposed to a number of feminist issues, which founder Phyllis Schlafly claimed were "extremely destructive" and "poisoned the attitudes of many young women." The organization believes only in a family consisting of a father, mother and children. They are supportive of women's role as "fulltime homemakers",[58] and opposed to same-sex marriage. Eagle Forum opposes abortion and has defended the push for government defunding of Planned Parenthood.[59]

.jpg)

Activities

After the 1972 proposal of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), Schlafly reorganized her efforts to defeat its ratification, founding the group "Stop ERA"[60] and starting the Eagle Forum Newsletter. In 1975 Stop ERA was renamed the Eagle Forum.[60] According to Schlafly, the passage of the ERA could "mean Government-funded abortions, homosexual schoolteachers, women forced into military combat and men refusing to support their wives." The newsletter began to circulate, and many conservative women wrote to their legislators, relaying the concerns voiced by Schlafly in the Eagle Forum Newsletter.[61] Support for The Eagle Forum grew with the support of many conservative women and various church groups, as did the opposition to the ERA. Many of the same women who had helped Schlafly distribute her book were involved with STOP ERA. Less than a year after its creation, STOP ERA had grown to several thousand members.[62]

The Pro-life Action League became active in Chicago in 1980 and tried to disrupt the ability of women to seek abortions by engaging in a variety of tactics including “sidewalk counseling,” sit-ins, and disrupting the water and sewage supplies to abortion clinics. The group's leader Joe Scheidler published a book in 1985 called Closed: 99 Ways to Stop Abortion.[63]

The methods used by Pro-life Action League would later become known as the "Chicago Method", which relied on an approach to sidewalk counseling that involves giving those about to enter an abortion facility copies of lawsuits filed against the facility or its physicians.[64]

Activism

Beginning in 1983, American Catholic Cardinal Joseph Bernardin argued that abortion, euthanasia, capital punishment, and unjust war are all related, and all wrong. He said that "to be truly 'pro-life,' you have to take all of those issues into account."[65]

Donations

Following the passage of abortion bans in Alabama, Georgia and Mississippi in early 2019, Pro-Life Action League saw an increase in donations and people asking to volunteer to help the organization.[66]

Violence

1982 saw a surge in attacks on abortion clinics in the United States with at least 4 arson attacks and 1 bombing. One attack occurred in Illinois and one in Virginia. Two occurred Florida. These 5 attacks caused over US$1.1 million in damage.[63] In August 1982, three men identifying as the Army of God kidnapped Hector Zevallos (a doctor and clinic owner) and his wife, Rosalee Jean, holding them for eight days.[67][63]

On September 30, 2000, John Earl, a Catholic priest, drove his car into the Northern Illinois Health Clinic after learning that the FDA had approved the drug RU-486. He pulled out an ax before being forced to the ground by the owner of the building, who fired two warning shots from a shotgun.[68]

Footnotes

- According to the Supreme Court's decision in Roe v. Wade:

(a) For the stage prior to approximately the end of the first trimester, the abortion decision and its effectuation must be left to the medical judgement of the pregnant woman's attending physician. (b) For the stage subsequent to approximately the end of the first trimester, the State, in promoting its interest in the health of the mother, may, if it chooses, regulate the abortion procedure in ways that are reasonably related to maternal health. (c) For the stage subsequent to viability, the State in promoting its interest in the potentiality of human life may, if it chooses, regulate, and even proscribe, abortion except where it is necessary, in appropriate medical judgement, for the preservation of the life or health of the mother.

Likewise, Black's Law Dictionary defines abortion as "knowing destruction" or "intentional expulsion or removal".

References

- https://www.cnn.com/2019/06/12/politics/illinois-governor-signs-abortion-protection-law/index.html

- https://www.nprillinois.org/post/other-states-restrict-abortion-rights-illinois-protects-and-expands

- Watson, Katie (20 Dec 2019). "Why We Should Stop Using the Term "Elective Abortion"". AMA Journal of Ethics. 20: E1175-1180. doi:10.1001/amajethics.2018.1175. PMID 30585581. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- Chamberlain, Pam; Hardisty, Jean (2007). "The Importance of the Political 'Framing' of Abortion". The Public Eye Magazine. 14 (1).

- "The Roberts Court Takes on Abortion". New York Times. November 5, 2006. Retrieved January 18, 2008.

- Brennan 'Dehumanizing the vulnerable' 2000

- Getek, Kathryn; Cunningham, Mark (February 1996). "A Sheep in Wolf's Clothing – Language and the Abortion Debate". Princeton Progressive Review.

- "Example of "anti-life" terminology" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2011-11-16.

- Goldstein, Norm, ed. The Associated Press Stylebook. Philadelphia: Basic Books, 2007.

- Castillo, Stephanie (2014-10-03). "States With More Abortion Restrictions Hurt Women's Health, Increase Risk For Maternal Death". Medical Daily. Retrieved 2019-05-27.

- "States pushing abortion bans have highest infant mortality rates". NBC News. Retrieved 2019-05-25.

- Mundell, E.J. (January 16, 2019). "Two-Thirds of Poor U.S. Women Can't Afford Menstrual Pads, Tampons: Study". US News & World Report. Retrieved May 26, 2019.

- Larimer, Sarah (January 8, 2016). "The 'tampon tax,' explained". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 11, 2016. Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- Bowerman, Mary (July 25, 2016). "The 'tampon tax' and what it means for you". USA Today. Archived from the original on December 11, 2016. Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- Hillin, Taryn. "These are the U.S. states that tax women for having periods". Splinter. Retrieved 2017-12-15.

- "Election Results 2018: Nevada Ballot Questions 1-6". KNTV. Retrieved 2018-11-07.

- Pollitt, Katha (1997-05-01). "Abortion in American History". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2019-05-26.

- Reagan, Leslie J. (1998-09-21). When Abortion Was a Crime: Women, Medicine, and Law in the United States, 1867–1973. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520216570.

- "When Abortion Was a Crime". www.theatlantic.com. Retrieved 2019-05-22.

- Buell, Samuel (1991-01-01). "Criminal Abortion Revisited". New York University Law Review. 66: 1774–1831.

- Reagan, Leslie J. (1997-01-30). When Abortion Was a Crime: Women, Medicine, and Law in the United States, 1867–1973. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520922068.

- "TRAP Laws Gain Political Traction While Abortion Clinics—and the Women They Serve—Pay the Price". Guttmacher Institute. 2013-06-27. Retrieved 2019-05-27.

- "Study: Abortions Are Safe When Performed By Nurse Practitioners, Physician Assistants, Certified Nurse Midwives". Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- "Are there *any* states working to protect abortion rights?". Well+Good. 2019-05-17. Retrieved 2019-05-25.

- "HB2495 101ST GENERAL ASSEMBLY". www.ilga.gov. Retrieved 2019-05-25.

- Anzel, Rebecca (2019-05-15). "'There is a war against women's rights': Illinois Democrats urge action to preserve abortion access". Daily Herald. Retrieved 2019-05-25.

- Lai, K. K. Rebecca (2019-05-15). "Abortion Bans: 8 States Have Passed Bills to Limit the Procedure This Year". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-05-24.

- "Illinois lawmakers rush to finish big to-do list, including new marijuana, abortion laws". USA TODAY. Retrieved 2019-06-02.

- O'connor, John (2019-05-29). "Illinois may expand abortion rights as other states restrict". AP NEWS. Retrieved 2019-06-02.

- Sfondeles, Tina (2019-05-28). "After emotional debate, Illinois House OKs abortion-rights measure". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2019-06-02.

- Veronica Stracqualursi and Chris Boyette. "Illinois and Nevada approve abortion rights bills that remove long-standing criminal penalties". CNN. Retrieved 2019-06-02.

- Arndorfer, Elizabeth; Michael, Jodi; Moskowitz, Laura; Grant, Juli A.; Siebel, Liza (December 1998). A State-By-State Review of Abortion and Reproductive Rights. DIANE Publishing. ISBN 9780788174810.

- Gould, Rebecca Harrington, Skye. "The number of abortion clinics in the US has plunged in the last decade — here's how many are in each state". Business Insider. Retrieved 2019-05-23.

- businessinsider (2018-08-04). "This is what could happen if Roe v. Wade fell". Business Insider (in Spanish). Retrieved 2019-05-24.

- "Here's Where Women Have Less Access to Planned Parenthood". Retrieved 2019-05-23.

- "Text-Only NPR.org : As Missouri's Last Abortion Provider Nears Closing, Neighboring Clinics Prepare". text.npr.org. Retrieved 2019-06-02.

- Lutz, Eric (2019-06-01). "Threat to Missouri abortion clinic leaves neighboring providers scrambling". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2019-06-02.

- Cates, Willard; Rochat, Roger (March 1976). "Illegal Abortions in the United States: 1972–1974". Family Planning Perspectives. 8 (2): 86. doi:10.2307/2133995. JSTOR 2133995. PMID 1269687.

- "Views about abortion by state - Religion in America: U.S. Religious Data, Demographics and Statistics". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 2019-05-23.

- "Abortion Incidence and Services in the United States, 1995-1996". Guttmacher Institute. 2005-06-15. Retrieved 2019-06-02.

- Jatlaoui, Tara C. (2017). "Abortion Surveillance — United States, 2014". MMWR. Surveillance Summaries. 66 (24): 1–48. doi:10.15585/mmwr.ss6624a1. ISSN 1546-0738. PMID 29166366.

- Jatlaoui, Tara C. (2018). "Abortion Surveillance — United States, 2015". MMWR. Surveillance Summaries. 67 (13): 1–45. doi:10.15585/mmwr.ss6713a1. ISSN 1546-0738. PMC 6289084. PMID 30462632.

- Jatlaoui, Tara C. (2019). "Abortion Surveillance — United States, 2016". MMWR. Surveillance Summaries. 68. doi:10.15585/mmwr.ss6811a1. ISSN 1546-0738.

- Francis Roberta W. "Frequently Asked Questions". Equal Rights Amendment. Alice Paul Institute. Archived from the original on 2009-04-17. Retrieved 2009-09-13.

- "Guttmacher Data Center". data.guttmacher.org. Retrieved 2019-05-24.

- Jessica Ravitz. "The surprising history of abortion in the U.S." CNN. Retrieved 2019-05-23.

- Larson, Jordan. "Timeline: The 200-Year Fight for Abortion Access". The Cut. Retrieved 2019-05-25.

- "Timeline of Important Reproductive Freedom Cases Decided by the Supreme Court". American Civil Liberties Union. Retrieved 2019-05-25.

- Margolin, Victor (1992). "SisterSerpents: A Radical Feminist Art Collective". AIGA Journal of Graphic Design. 10 (2).

- George, Erika (March 12, 1991). "Hissing with anger: SisterSerpents exhibit art". The Chicago Maroon.

- Bacon, John. "Abortion rights supporters' voices thunder at #StopTheBans rallies across the nation". USA TODAY. Retrieved 2019-05-25.

- FOX. "Thousands protest restrictive abortion legislation at #StopTheBans events nationwide". WNYW. Retrieved 2019-05-25.

- Low, Matt Donnelly, Gene Maddaus, Elaine; Donnelly, Matt; Maddaus, Gene; Low, Elaine (2019-05-28). "Netflix the Only Hollywood Studio to Speak Out in Attack Against Abortion Rights (EXCLUSIVE)". Variety. Retrieved 2019-06-02.

- "Thousands of phone calls fight video gambling law". WREX. January 20, 2010. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 9, 2012.

- Illinois Family Institute. "Issues We Follow". Retrieved July 8, 2012.

- Illinois Family Institute. "Homosexuality". Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- Ford, Lynne E. (2010-05-12). Encyclopedia of Women and American Politics - Lynne E. Ford - Google Boeken. ISBN 9781438110325. Retrieved 2012-03-26.

- "Join Eagle Forum and Phyllis Schlafly -- Join Eagle Forum so you will have a voice at the U.S. Capitol and at State Capitols". www.eagleforum.org. Retrieved 2015-12-02.

- "Planned Parenthood's Odious Activities - Eagle Forum". Eagle Forum. Retrieved 2015-12-02.

- Roads to Dominion: Right-Wing Movements and Political Power in the United States Sara Diamond. Guilford Press, 1995.

- "Phyllis Schlafly". MAKERS. Retrieved 2015-12-02.

- Critchlow, Donald T. (2005-01-01). Phyllis Schlafly and Grassroots Conservatism: A Woman's Crusade. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691070024.

stop%2520era.

- Jacobson, Mireille; Royer, Heather (December 2010). "Aftershocks: The Impact of Clinic Violence on Abortion Services". American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 3: 189–223. doi:10.1257/app.3.1.189.

- "Controversy in the Activist Movement", Pro-Life Action News, August 2000 Archived 2007-06-18 at the Wayback Machine.

- Kaczor, Christopher Robert (2006). The Edge of Life: Human Dignity and Contemporary Bioethics. Philosophy and Medicine. 85. Springer. p. 148. ISBN 9781402031564.

- Pesce, Nicole Lyn. "Abortion bans are spurring donations to Planned Parenthood, the National Organization for Women, and more". MarketWatch. Retrieved 2019-05-27.

- Baird-Windle, Patricia & Bader, Eleanor J., (2001), Targets of Hatred: Anti-Abortion Terrorism, New York, St. Martin's Press, ISBN 978-0-312-23925-1

- "CNN.com - Axe-wielding priest attacks abortion clinic - September 30, 2000". web.archive.org. 2012-10-19. Retrieved 2019-05-22.