Solar eclipses

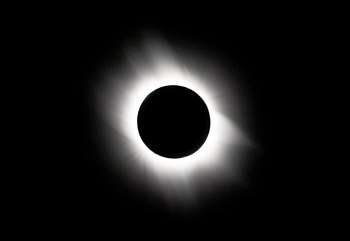

A solar eclipse is an astronomical phenomenon, in which the sun is obscured by the moon. Total eclipses, in which darkness falls and the sun's normally invisible atmosphere is seen around a blackened sun, attract many travellers.

Understand

There are several types of solar eclipse:

- total, in which the normally visible parts of the sun are totally obscured, causing night-like darkness to fall for several minutes, and the corona — the sun's normally invisible atmosphere — to be seen radiating around the black circle of the moon

- annular, in which the moon obscures the centre of the sun, causing a bright ring to be seen around the dark moon

- hybrid, in which at various points along the eclipse's path either an annular or total eclipse is seen

- partial, in which a fraction of the sun's surface is obscured by part of the moon

Total eclipses are the most dramatic solar eclipse, a very strange and beautiful spectacle. A total solar eclipse occurs somewhere on Earth once or twice most years but is only visible from a narrow ribbon of the surface — the eclipse's path — with a partial eclipse experienced in a wider area. Partial eclipses are the least dramatic: unless one is viewing the eclipse deliberately it often just appears to be a somewhat dim day, as if overcast.

Annular and total eclipses begin with a partial eclipse in which progressively more of the sun is eclipsed until the maximum eclipse, called totality for total eclipses. The partial eclipse may last one hour or more either side of totality; totality is only a few minutes in length or less.

Total eclipses, like many orbital phenomena, can be predicted accurately very far in advance, and attract many travellers anticipating the sight. They can be easily seen and appreciated with the naked eye, but amateur astronomers frequently travel to them with telescopes. Some travellers, umbraphiles, make it a priority to travel to see as many eclipses as possible.

Viewing a total solar eclipse is a chancy thing: simple local cloud cover changes it from a eclipse viewing to a momentarily dark cloudy day!

Why...?

Why do eclipses happen?

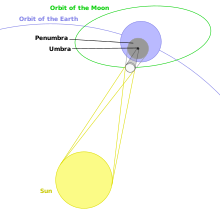

- Solar eclipses happen when the moon is directly in between the earth and the sun. Another way to think about it is that the moon can cast a shadow, and if you're in that shadow, it'll look like the moon is covering up the sun or part of it. That's an eclipse.

Why isn't there a solar eclipse every month?

- There would be if the moon's orbit around the earth was in the same plane as the earth's orbit around the sun. Instead, the moon's orbit is tilted, so its shadow doesn't usually hit the earth, which means that eclipses aren't usually visible from the earth's surface. Everything lines up just right for an eclipse only 2–5 times a year, and a total eclipse is only possible at most twice in a given year.

Why are some solar eclipses total while others are annular?

- Both the moon and the sun vary in their distance from the earth. As a result, sometimes the moon looks slightly smaller than the sun (as in an annular eclipse), and sometimes it looks the same size or slightly larger (as in a total eclipse).

Do total solar eclipses happen on other planets like they do on Earth?

- Yes, on some planets, but not very many. Earth has the lucky coincidence of a sun and moon that look roughly the same size to a viewer on the surface. The only other planet in our solar system with similar eclipses is Saturn, and due to the shapes and orbits of its moons, the eclipses there wouldn't be as spectacular as they are on Earth.

Why do the sun and the moon look roughly the same size to a viewer on Earth's surface?

- The sun is 400 times the diameter of the moon, but it also happens to be roughly 400 times as far away.

Get in

Because solar eclipses, especially those viewable easily from land, are fairly rare, there are two problems with getting to them: the first is finding transport to the location at all and the second is booking it before your competition does. Solar eclipses can attract from thousands to hundreds of thousands of viewers, which can overwhelm the capacity of local transport and accommodation. If the eclipse is crossing a well-resourced tourist area (like the 2012 eclipse visible from Cairns, a tourist city in Australia), you should ideally book several months in advance but there may be some availability close to the eclipse. If the eclipse is off the beaten track, you may need to make arrangements a year or more in advance. Expect at least peak season pricing. Planes and trains will get booked up and tickets may become expensive, so book early and get seat reservations. If you waited too long and everything seems to be booked up, it might help to search for more creative options for transportation and accommodation—sometimes people will arrange charter buses or rent out their backyards to eclipse watchers. If you have the means, it's wise to make bookings for two different locations; that way, a few days before the eclipse you can check the weather forecast and head to the spot with less chance of cloud cover.

Sometimes transportation companies offer special service with extra planes, trains, buses, or boats specifically for viewing the eclipse or getting people to good viewing locations. Cruise ships often have special itineraries into paths of totality, and this may be preferable if your willingness to travel off the beaten track is limited. They may also be able to search for a cloud-free viewing area within reasonable limits, an opportunity you are less likely to have on land. Helicopter or plane flights above cloud cover may be available if the eclipse is over an area with airstrips. While all of these tend to sell out rather quickly as well, they can be a unique way to make the journey relaxing and fun and to be among like-minded people on the way to the viewing destination.

Plan lots of extra time to get in and out. Especially in small towns that are good viewing locations, you can expect horrible traffic jams and crowded trains and buses. There are also likely to be more road accidents than usual caused by extra vehicles, tired drivers, and strained emergency services. In some cases, the journey can take 2–3 times what it normally would or even longer. Avoid the worst of the delays by arriving at your viewing location extra early and leaving late—ideally, arrive a day or two before the eclipse and depart a day or two after. Make contingency plans in case you end up being unable to get home when you thought you would. If driving, be prepared with different routes in case of traffic, and have the directions saved or printed out in case cell reception is poor.

Out-of-the-way places that are on the path of totality may see their populations swell by a factor of 10 or more for the eclipse. Local resources may be stretched beyond their limits, so bring extra food and water, and if you're driving, make sure you have plenty of fuel. Be prepared for long lines to use toilets that may not be very clean. Don't rely on your cell phone for communication or navigation—the local cell towers may be overwhelmed by the influx of people.

Bring an extra layer of clothing too—the decreased sunlight will make it chilly for a few minutes, even in a partial eclipse.

Destinations

Here is a list of several total, annular and hybrid solar eclipses in the near future.

- 2019, July 2 (total). The pathway crosses the south Pacific ocean, but the final part of the totality path crosses Chile and Argentina. (NASA chart)

- 2019, December 26 (annular). The pathway is at a maximum over Sumatra (Indonesia) and Singapore, but the path starts in Saudi Arabia, and passes through Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, Oman, southern India, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, and touches Borneo and Guam. (NASA chart)

- 2020, June 21 (annular). The pathway passes through Congo-Brazzaville, Congo-Kinshasa, South Sudan, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Oman, Pakistan, India, China, and Taiwan. The greatest eclipse is over parts of the Himalayan North of India and Tibet in China. (NASA chart)

- 2020, December 14 (total). The pathway crosses the south Pacific and south Atlantic, with the path of totality crossing southern Chile and Neuquen and Rio Negro provinces in Argentina. (NASA chart)

- 2021, June 10 (annular). Mostly over remote regions, with the path crossing parts of Canada, Russia, and Greenland. (NASA chart)

- 2021, December 4 (total). The path of totality crosses West Antarctica, with a partial eclipse visible from elsewhere in Antarctica. (NASA chart)

- 2022 will see some partial solar eclipses, but no annular or total solar eclipses on the Earth's surface.

- 2023, April 20 (hybrid). Over Indonesia, with the path of totality/annularity crossing Papua and Nusa Tenggara. A partial eclipse will be visible from elsewhere in Indonesia as well as Papua New Guinea and Australia. (NASA chart)

- 2023, October 14 (annular). Crosses a significant portion of the Americas, including parts of the United States, Mexico, Belize, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, Colombia, and Brazil. The greatest eclipse will be in Central America, around Nicaragua and Costa Rica. (NASA chart)

- 2024, April 8 (total). The pathway crosses Mexico, the United States of America and Canada, directly south of the beaten-path Windsor-Quebec Corridor and continuing into New Brunswick. In or near the path of totality are Windsor-Detroit, Cleveland, Toronto-Buffalo, Montréal-Burlington, Boston and much of New England, with the greatest eclipse over Northern Mexico. (NASA chart)

- 2024, October 2 (annular). Mostly over the Pacific Ocean, but the path also crosses Argentinian and Chilean Patagonia. (NASA chart)

There are also NASA tables and maps of eclipses: table from 2011 to 2020, table from 2021 to 2030, table from 2031 to 2040, map from 2001 to 2020 and map from 2021 to 2040.

Partial eclipses

- 2022:

- April 30. Mostly over the South Pacific, but will also be visible over Chile. (NASA chart)

- October 25. Will be visible in most of Europe, european part of Russia and the Urals, Central Asia, the Middle East as well as significant chunks of North and East Africa. (NASA chart)

See

- View the eclipse directly, by looking at the sun. See Stay safe: only totality can be observed safely without special precautions!

- View the eclipse through a pinhole camera. Take two sheets of cardboard and make a small hole in one, and shine sunlight through that hole onto the other. The circle cast on the second sheet of cardboard (the equivalent of the retina of an eye or the sensor of a camera) will change its shape as a partial eclipse progresses.

- View the eclipse from the ocean. In addition to cruise ship itineraries, coastal areas will often have day cruises available to view the eclipse, this may avoid crowded public areas, and the vessel may be able to avoid local cloud cover. As with transport in general, book early.

- Photograph the eclipse. Beware: solar photography is not safe for camera sensors or film unless the lens is protected from the sun with a solar filter, which can be purchased from astronomy shops.

- View the eclipse through a telescope. A solar filter must be over the lens of the telescope if viewing directly: some telescopes can be adapted to project an image instead.

- Look at the strange crescent-shaped shadows during a partial, total, or annular eclipse. If you bring a straw hat with a loose weave, you can use it to produce dozens of the little crescents.

- During a total eclipse, watch out for well-known phenomena before, during and after the eclipse:

- Just before the eclipse, the enormous shadow of the moon will approach from the west at a very rapid pace: some people find this frightening. (If it's a morning eclipse you may have your back to this phenomenon!)

- Just prior to and after the eclipse, a phenomenon known as Baily's beads may be visible, where the sun is first visible through craters on the side of the moon, creating points of light on the edge of the moon's shadow.

- During totality, birds may roost and generally the quiet of night will fall briefly. A partial eclipse will not visibly darken the surrounding countryside.

- While ideally this is avoided by local authorities, it is not uncommon for automatic sensing streetlights to suddenly turn on, and rather spoil the show!

Learn

Eclipses provide a unique opportunity to do science. Famously, Einstein's theory of relativity was tested during a 1919 eclipse over Príncipe which allowed researchers to see how the gravity of the sun caused starlight to bend. Nowadays, lots of science is done during eclipses, from observing the sun's corona to investigating animal responses to the sudden change in light. Travellers are welcome and encouraged to participate, with both individual scientists and large organizations like NASA asking for amateur astronomers and ordinary people to help them gather data. Search for "eclipse citizen science" online to see how you can help.

Stay safe

Never look at the Sun with the unaided eye or with a camera or telescope, not even for a second and not even if only 1% of the Sun is visible. This may seriously damage your eye and even make you blind. Always use an approved solar filter either directly over your eyes for unaided viewing, or over the lens of a camera or telescope. You can use:

- Eclipse glasses: CE certified or conforming to ISO 12312-2 or EN 1836 & AS/NZS 1338.1. These are usually cheap cardboard glasses costing around US$3 to $5.

- Welder's goggles rated 12–14, the highest ratings for blocking radiation.

- Solar filters for cameras and telescopes, available from astronomy shops.

Eclipse glasses will often be available for sale at prime viewing locations. You might not need a pair for each person in your party—eclipses are slow enough that you should be able to hand a pair back and forth between two or three people if necessary.

If using a camera or telescope the lens itself must be protected: it is not sufficient to look through the viewfinder with eclipse glasses as the lens has magnified the sun's power even further and may still damage your eye. In addition, the sun's power will destroy camera sensors/film if you haven't got a filter on the lens.

Do not use:

- anything designed for vision/photography in normal bright light conditions, like sunglasses, or standard photography filters. These are millions of times less powerful than the filters you need to gaze at the sun.

- lesser rated welder's goggles

- exposed film negatives

- any stacked lesser protections

- any non-certified protections

- eclipse glasses with damage such as scratches or tears

Beware of fake eclipse glasses. Some unscrupulous manufacturers have placed the ISO logo on glasses that do not actually meet the organization's standards, so make sure your glasses come from a reputable source. Glasses from science museums or astronomical organizations are almost certainly good to go; the American Astronomical Society also provides a partial list of reputable vendors.

As the moon fully obscures the sun during total eclipses it becomes safe to look without a filter and see the beautiful corona (the sun's atmosphere). Have your eye protection ready for the end of totality.