Zhu Yunming

Zhu Yunming (Chinese: 祝允明; 1461–1527[1]) was a Chinese calligrapher, poet, writer, and scholar-official of the Ming dynasty, known as one of the "Four Talents of Wu" (Suzhou). Most admired for his accomplishment in calligraphy, he is also a popular cultural figure for his uninhibited lifestyle and iconoclastic thinking.[2] He criticized the orthodox Neo-Confucianism of Zhu Xi and admired the philosophy of mind advocated by Wang Yangming.[2] He wrote a large number of essays that criticize traditional values,[2] and was an influence on the iconoclastic philosopher Li Zhi.

| Zhu Yunming | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 祝允明 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

Biography

Zhu was born in 1461 in Changzhou County, modern Suzhou, Jiangsu Province. His courtesy name was Xizhe (希哲), and art name Zhishan (枝山).[3] Born with a supernumerary thumb on one hand,[4] Zhu gave himself the sobriquet "Zhizhi Scholar" (枝指生; zhizhi refers to preaxial polydactyly in Chinese).[5][6] He was said to have been able to write calligraphy with large characters at the tender age of four and compose poetry by the age of eight.[3] He became a certified student at 16, and succeeded in the provincial examination of 1492, but never passed metropolitan examinations.[3]

Zhu was appointed as the county magistrate of Xingning, Guangdong, in 1514. He served as the principal editor of the Gazetteer of Xingning County (in the reign of Zhengde), during his five-year term. In 1521, he was promoted to Controller-General of Yingtian Prefecture (modern Nanjing). He resigned in less than a year on a plea of illness. He dedicated the rest of his life to writing and died in 1527.[3]

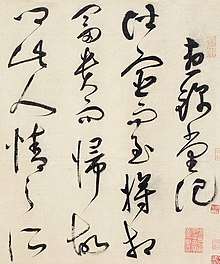

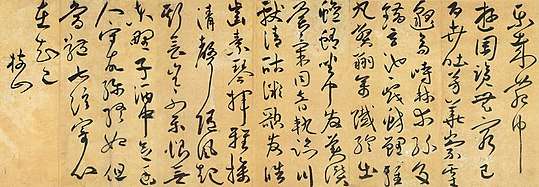

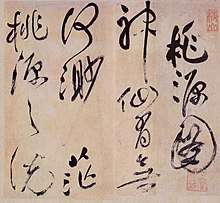

Together with Tang Yin, Wen Zhengming and Xu Zhenqing, Zhu was one of the "Four Talents of Wu (Suzhou)" (吴中四才子), his calligraphy is the most noted in the quartet. He excelled at small standard script (xiaokai), but was of wild-cursive (kuangcao) fame.[7] His friends attributed his affinity for this highly expressive calligraphy to his impetuous personality.[7]

Zhu was also known as an unorthodox thinker against Neo-Confucianism. In his later life, he described himself as a "wild man".[2] He finished various collections of miscellaneous notes. Some scholars believe that his work of judgements on historical personalities influenced Li Zhi's Cang Shu.[1]

In popular culture

Zhu's nonconformist thinking and lifestyle have made him a subject of popular legends. Stories about him have been written into a novel, The Romance of Zhu Yunming.[4]

Selected works

- 懷星堂集 [Collection of Huaixing Hall]

- 蘇材小纂 [Collected Biographies of Eminent People from Suzhou]

- 前闻記 [Memoir of By-gone Events]

- 猥谈 [Trivial Talks]

References

- Denis Crispin Twitchett; John King Fairbank (1978). The Cambridge History of China, Volume 7, Part 1. Cambridge University Press. p. 730. ISBN 978-0-521-24332-2.

- Kang-i Sun Chang; Stephen Owen (2010). The Cambridge History of Chinese Literature: From 1375. Cambridge University Press. pp. 36–42. ISBN 978-0-521-85559-4.

- "Introduction [of Zhu Yunming]". National Palace Museum.

- Tony Barnstone; Ping Chou (2005). The Anchor Book of Chinese Poetry. Anchor Books. p. 307. ISBN 978-0-385-72198-1.

- Goodrich, Fang, Luther Carrington, Chaoying (1976). Dictionary of Ming Biography, 1368–1644. Columbia University Press. pp. 570–576. ISBN 0-231-03801-1.

- According to Dictionary of Ming Biography, 1368–1644, Zhu had an extra thumb on his left hand, but in Qian Qianyi's account, it was on his right hand, see Qian's Liechao Shiji Xiaozhuan

- "PUAM – Asian Art Collection". Princeton University. Retrieved 26 June 2018.