Molar (tooth)

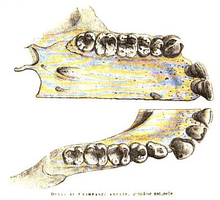

The molars or molar teeth are large, flat teeth at the back of the mouth. They are more developed in mammals. They are used primarily to grind food during chewing. The name molar derives from Latin, molaris dens, meaning "millstone tooth", from mola, millstone and dens, tooth. Molars show a great deal of diversity in size and shape across mammal groups.

| Molar | |

|---|---|

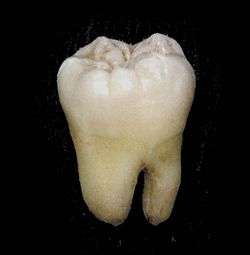

A lower wisdom tooth after extraction. | |

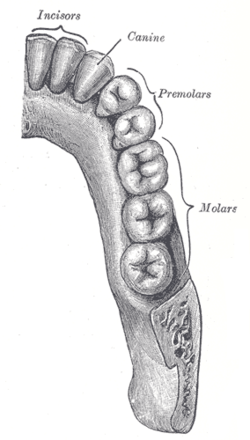

Permanent teeth of right half of lower dental arch, seen from above: In this diagram, a healthy wisdom tooth (third, rearmost molar) is included | |

| Details | |

| Artery | Posterior superior alveolar artery |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | dentes molaers |

| MeSH | D008963 |

| TA | A05.1.03.007 |

| FMA | 55638 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Human anatomy

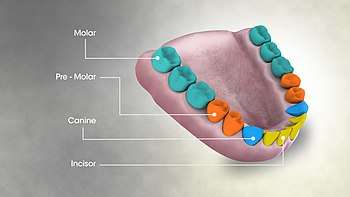

In humans, the molar teeth have either four or five cusps. Adult humans have 12 molars, in four groups of three at the back of the mouth. The third, rearmost molar in each group is called a wisdom tooth. It is the last tooth to appear, breaking through the front of the gum at about the age of 20, although this varies from individual to individual. Race can also affect the age at which this occurs, with statistical variations between groups.[1] In some cases, it may not even erupt at all.

The human mouth contains upper (maxillary) and lower (mandibular) molars. They are: maxillary first molar, maxillary second molar, maxillary third molar, mandibular first molar, mandibular second molar, and mandibular third molar.

Mammal evolution

In mammals, the crown of the molars and premolars is folded into a wide range of complex shapes. The basic elements of the crown are the more or less conical projections called cusps and the valleys that separate them. The cusps contain both dentine and enamel, whereas minor projections on the crown, called crenulations, are the result of different enamel thickness. Cusps are occasionally joined to form ridges and expanded to form crests. Cingula are often incomplete ridges that pass around the base of the crown.[2]

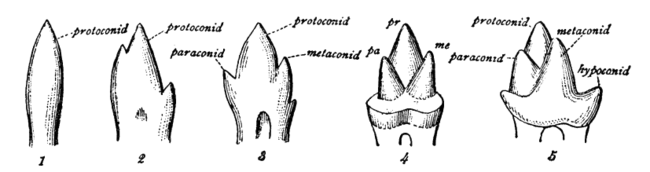

Mammalian, multicusped cheek teeth probably evolved from single-cusped teeth in synapsids, although the diversity of therapsid molar patterns and the complexity in the molars of the earliest mammals make determining how this happened impossible. According to the widely accepted "differentiation theory", additional cusps have arisen by budding or outgrowth from the crown, while the rivalling "concrescence theory" instead proposes that complex teeth evolved by the clustering of originally separate conical teeth. Therian mammals (placentals and marsupials) are generally agreed to have evolved from an ancestor with tribosphenic cheek teeth, with three main cusps arranged in a triangle.[2]

Morphology

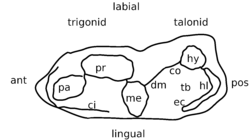

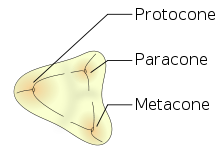

Each major cusp on an upper molar is called a cone and is identified by a prefix dependent on its relative location on the tooth: proto-, para-, meta-, hypo-, and ento-. Suffixes are added to these names: -id is added to cusps on a lower molar (e.g., protoconid); -ule to a minor cusp (e.g., protoconulid). A shelf-like ridge on the lower part of the crown (on an upper molar) is called a cingulum; the same feature on the lower molar a cingulid, and a minor cusp on these, for example, a cingular cuspule or conulid.[3]

Tribosphenic

The design that is considered one of the most important characteristics of mammals is a three-cusped shape called a tribosphenic molar. This molar design has two important features: the trigonid, or shearing end, and the talonid, or crushing heel. In modern tribosphenic molars, the trigonid is towards the front of the jaw and the talonid is towards the rear.

The tribosphenic tooth is found in insectivores and young platypuses (adults have no teeth). Upper molars look like three-pointed mountain ranges; lowers look like two peaks and a third off to the side.

The tribosphenic design appears primitively in all groups of mammals. Some paleontologists believe that it developed independently in monotremes (or australosphenidans), rather than being inherited from an ancestor that they share with marsupials and placentals (or boreosphenidans); but this idea has critics and the debate is still going on.[4] For example, the dentition of the Early Cretaceous monotreme Steropodon is similar to those of Peramus and dryolestoids, which suggests that monotremes are related to some pre-tribosphenic therian mammals,[5] but, on the other hand, the status of neither of these two groups is well-established.

Some Jurassic mammals, such as Shuotherium and Pseudotribos, have "reversed tribosphenic" molars, in which the talonid is towards the front. This variant is regarded as an example of convergent evolution.[6]

From the primitive tribosphenic tooth, molars have diversified into several unique morphologies. In many groups, a fourth cusp, the hypocone (hypoconid), subsequently evolved (see below).

Quadrate

Quadrate (also called quadritubercular or euthemorphic) molars have an additional fourth cusp on the lingual (tongue) side called the hypocone, located posterior to the protocone. Quadrate molars appeared early in mammal evolution and are present in many species, including hedgehogs, raccoons, and many primates, including humans.[7] There may be a fifth cusp.

In many mammals, additional smaller cusps called conules appear between the larger cusps. They are named after their locations, e.g. a paraconule is located between a paracone and a metacone, a hypoconulid is located between a hypoconid and an entoconid.[7]

Bunodont

In bunodont molars, the cusps are low and rounded hills rather than sharp peaks. They are most common among omnivores such as pigs, bears, and humans.[7] Bunodont molars are effective crushing devices and often basically quadrate in shape.[8]

Hypsodont

Hypsodont dentition is characterized by high-crowned teeth and enamel that extends far past the gum line, which provides extra material for wear and tear.[9] Some examples of animals with hypsodont dentition are cattle and horses, all animals that feed on gritty, fibrous material. Hypsodont molars can continue to grow throughout life, for example in some species of Arvicolinae (herbivorous rodents).[7]

Hypsodont molars lack both a crown and a neck. The occlusal surface is rough and mostly flat, adapted for crushing and grinding plant material. The body is covered with cementum both above and below the gingival line, below which is a layer of enamel covering the entire length of the body. The cementum and the enamel invaginate into the thick layer of dentin.[10]

Brachydont

The opposite condition to hypsodont is called brachydont or brachyodont (from brachys, "short"). It is a type of dentition characterized by low-crowned teeth. Human teeth are brachydont.[7]

A brachydont tooth has a crown above the gingival line and a neck just below it, and at least one root. A cap of enamel covers the crown and extends down to the neck. Cementum is only found below the gingival line. The occlusal surfaces tend to be pointed, well-suited for holding prey and tearing and shredding.[10]

Zalambdodont

Zalambdodont molars have three cusps, one larger on the lingual side and two smaller on the labial side, joined by two crests that form a V- or λ-shape. The larger inner cusp might be homologous with the paracone in a tribosphenic molar, but can also be fused with the metacone. The protocone is typically missing. The two smaller labial cusps are located on an expanded shelf called the stylar shelf. Zalambdodont molars are found in, for example, golden moles and solenodons.[7]

Dilambdodont

Like zalambdodont molars, dilambdodont molars have a distinct ectoloph, but are shaped like two lambdas or a W. On the lingual side, at the bottom of the W, are the metacone and paracone, and the stylar shelf is on the labial side. A protocone is present lingual to the ectoloph. Dilambdodont molars are present in shrews, moles, and some insectivorous bats.[7]

Lophodont

Lophodont teeth are easily identified by the differentiating patterns of ridges or lophs of enamel interconnecting the cusps on the crowns. Present in most herbivores, these patterns of lophs can be a simple, ring-like edge, as in mole rats, or a complex arrangement of series of ridges and cross-ridges, as those in odd-toed ungulates, such as equids.[8]

Lophodont molars have hard and elongated enamel ridges called lophs oriented either along or perpendicular to the dental row. Lophodont molars are common in herbivores that grind their food thoroughly. Examples include tapirs, manatees, and many rodents.[7]

When two lophs form transverse, often ring-shaped, ridges on a tooth, the arrangement is called bilophodont. This pattern is common in primates, but can also be found in lagomorphs (hares, rabbits, and pikas) and some rodents.[7][8]

Extreme forms of lophodonty in elephants and some rodents (such as Otomys) is known as loxodonty.[7] The African elephant belongs to a genus called Loxodonta because of this feature.

Selenodont

In selenodont molars (so-named after moon goddess Selene), the major cusp is elongated into crescent-shaped ridge. Examples include most even-toed ungulates, such as cattle and deer.[7][8]

Secodont

Many carnivorous mammals have enlarged and blade-like teeth especially adapted for slicing and chopping called carnassials. A general term for such blade-like teeth is secodont or plagiaulacoid.[7]

See also

- Dental formula

- Polyphyodont

Notes

- Rozkovcová, E; Marková, M; Dolejsí, J (1999). "Studies on agenesis of third molars amongst populations of different origin". Sbornik Lekarsky. 100 (2): 71–84. PMID 11220165.

- Zhao, Weiss & Stock 2000, Acquisition of multi-cusped cheek teeth in mammals, p. 154

- Myers et al. 2013b

- Stokstad 2001

- Luo, Cifelli & Kielan-Jaworowska 2001

- Luo, Ji & Yuan 2007

- Myers et al. 2013a

- Lawlor 1979, pp. 13–4

- Flynn, Wyss & Charrier 2007

- Kwan, Paul W.L. (2007). "Digestive system I" (PDF). Tufts University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-09-13. Retrieved 2013-05-18.

References

- Flynn, John J.; Wyss, André R.; Charrier, Reynaldo (May 2007). "South America's Missing Mammals". Scientific American: 68–75. OCLC 17500416. Retrieved 2013-05-11.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lawlor, T.E. (1979). "The Mammalian Skeleton" (PDF). Handbook to the Orders and Families of Living Mammals. Mad River Press. ISBN 978-0-916422-16-5. OCLC 5763193. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-07-01. Retrieved 2013-05-12.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Luo, Zhe-Xi; Cifelli, Richard L.; Kielan-Jaworowska, Zofia (4 January 2001). "Dual origin of tribosphenic mammals". Nature. 409 (6816): 53–7. doi:10.1038/35051023. PMID 11343108.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Luo, Z.-X.; Ji, Q.; Yuan, C.-X. (November 2007). "Convergent dental adaptations in pseudo-tribosphenic and tribosphenic mammals". Nature. 450 (7166): 93–97. doi:10.1038/nature06221. PMID 17972884.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Myers, P.; Espinosa, R.; Parr, C. S.; Jones, T.; Hammond, G. S.; Dewey, T. A. (2013a). "The Basic Structure of Cheek Teeth". Animal Diversity Web, University of Michigan. Retrieved 2013-05-12.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Myers, P.; Espinosa, R.; Parr, C. S.; Jones, T.; Hammond, G. S.; Dewey, T. A. (2013b). "The Diversity of Cheek Teeth". Animal Diversity Web, University of Michigan. Archived from the original on 2013-04-05. Retrieved 2013-05-12.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stokstad, E. (January 2001). "Tooth Theory Revises History of Mammals". Science. 291 (5501): 26. doi:10.1126/science.10.1126/science.291.5501.26. PMID 11191993.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zhao, Z.; Weiss, K. M.; Stock, D. W. (2000). "Development and evolution of dentition patterns and their genetic basis". In Teaford, Mark F; Smith, Moya Meredith; Ferguson, Mark WJ (eds.). Development, Function and Evolution of Teeth. Cambridge University Press. pp. 152–72. ISBN 978-0-511-06568-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Overview of molar morphology and terminology- Paleos.com