Wisdom tooth

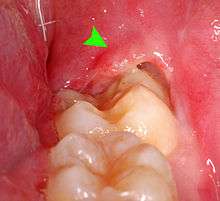

A wisdom tooth or third molar is one of the three molars per quadrant of the human dentition. It is the most posterior of the three. The age at which wisdom teeth come through (erupt) is variable,[1] but generally occurs between late teens and early twenties.[2] Most adults have four wisdom teeth, one in each of the four quadrants, but it is possible to have none, fewer, or more, in which case the extras are called supernumerary teeth. Wisdom teeth may get stuck (impacted) against other teeth if there is not enough space for them to come through normally. While the impaction does not cause movement of other teeth,[3] it can cause tooth decay if oral hygiene becomes more difficult. Wisdom teeth which are partially erupted through the gum may also cause inflammation and infection in the surrounding gum tissues, termed pericoronitis. Wisdom teeth are often extracted when or even before these problems occur. However, some, including the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in the UK, recommend against the prophylactic extraction of disease-free impacted wisdom teeth.[3][4][5]

| Wisdom tooth | |

|---|---|

Wisdom teeth | |

3D CT of an impacted wisdom tooth near the inferior alveolar nerve | |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D008964 |

| TA | A05.1.03.008 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Structure

Variation

Agenesis of wisdom teeth differs by population, ranging from practically zero in Aboriginal Tasmanians to nearly 100% in indigenous Mexicans[6] (see research paper with world map showing prevalence). The difference is related to the PAX9, and MSX1 gene (and perhaps other genes).[7][8][9][10]

Age of eruption

There is significant variation between the reported age of eruption of wisdom teeth between different populations.[11] For example, wisdom teeth tend to erupt earlier in people with African heritage compared to Asian and European heritage.[11]

Generally wisdom teeth erupt most commonly between age 17 and 21.[1] Eruption may start as early as age 13 in some groups[11] and typically occurs before the age of 25.[12] If they have not erupted by age 25, oral surgeons generally consider that the tooth will not erupt spontaneously by itself.[2]

Function

Wisdom teeth are vestigial third molars that helped human ancestors to grind plant tissue. It is thought that the skulls of human ancestors had larger jaws with more teeth, which possibly helped to chew foliage to compensate for a lack of ability to efficiently digest the cellulose that makes up a plant cell wall.[13] After the advent of agriculture over 10,000 years ago, soft human diets became the norm, including carbohydrate and high energy foods. Such diets typically result in jaws growing with less forward growth than our paleolithic ancestors and not enough room for the wisdom teeth.[14]

Clinical significance

Wisdom teeth (often notated clinically as M3 for third molar) have long been identified as a source of problems and continue to be the most commonly impacted teeth in the human mouth. The oldest known impacted wisdom tooth belonged to a European woman of the Magdalenian period (18,000–10,000 BCE).[15] A lack of room to allow the teeth to erupt results in a risk of periodontal disease and dental cavities that increases with age.[16] Less than 2% of adults age 65 years or older maintain the teeth without cavities or periodontal disease and 13% maintain unimpacted wisdom teeth without cavities or periodontal disease.[17]

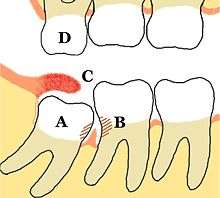

Impacted wisdom teeth are classified by the direction and depth of impaction, the amount of available space for tooth eruption and the amount soft tissue or bone that covers them. The classification structure allows clinicians to estimate the probabilities of impaction, infections and complications associated with wisdom teeth removal.[16] Wisdom teeth are also classified by the presence of symptoms and disease.[18]

Treatment of an erupted wisdom tooth is the same as any other tooth in the mouth. If impacted, treatment can be restoration, local treatment to the infected tissue overlying the impaction,[19]:440–441 extraction[20] or coronectomy.[21]

History

Although formally known as third molars, the common name is wisdom teeth because they appear so late – much later than the other teeth, at an age where people are presumably "wiser" than as a child, when the other teeth erupt.[22] The term probably came as a translation of the Latin dens sapientiae. Their eruption has been known to cause dental issues for millennia; it was noted at least as far back as Aristotle:

The last teeth to come in man are molars called 'wisdom-teeth', which come at the age of twenty years, in the case of both sexes. Cases have been known in women upwards of eighty years old where at the very close of life the wisdom-teeth have come up, causing great pain in their coming; and cases have been known of the like phenomenon in men too. This happens, when it does happen, in the case of people where the wisdom-teeth have not come up in early years.

— Aristotle, The History of Animals[23]

Nonetheless, molar impaction was relatively rare prior to the modern era. With the Industrial Revolution, the affliction became ten times more common, owing to the new prevalence of soft, processed, and sugary foods.[24]

See also

References

- McCoy, JM (September 2012). "Complications of retention: pathology associated with retained third molars". Atlas of the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America. 20 (2): 177–95. doi:10.1016/j.cxom.2012.06.002. ISBN 978-1455747887. PMID 23021395.

- Swift, JQ; Nelson, WJ (September 2012). "The nature of third molars: are third molars different than other teeth?". Atlas of the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America. 20 (2): 159–62. doi:10.1016/j.cxom.2012.07.003. PMID 23021392.

- Friedman, JW (September 2007). "The prophylactic extraction of third molars: a public health hazard". American Journal of Public Health. 97 (9): 1554–9. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2006.100271. PMC 1963310. PMID 17666691.

- "1 Guidance | Guidance on the Extraction of Wisdom Teeth | Guidance | NICE". www.nice.org.uk. Retrieved 2019-12-03.

- "Opposition to Prophylactic Removal of Third Molars (Wisdom Teeth)". www.apha.org. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- Rozkovcová, E.; Marková, M.; Dolejší, J. (1999). "Studies on agenesis of third molars amongst populations of different origin". Sborník Lékařský. 100 (2): 71–84. PMID 11220165.

- Pereira, Tiago V.; Salzano, Francisco M.; Mostowska, Adrianna; Trzeciak, Wieslaw H.; Ruiz-Linares, Andrés; Chies, José A. B.; Saavedra, Carmen; Nagamachi, Cleusa; et al. (2006). "Natural selection and molecular evolution in primate PAX9 gene, a major determinant of tooth development". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 103 (15): 5676–81. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103.5676P. doi:10.1073/pnas.0509562103. JSTOR 30050159. PMC 1458632. PMID 16585527.

- Bonczek, O; Balcar, VJ; Šerý, O (2017). "PAX9 gene mutations and tooth agenesis: A review". Clin Genet. 92 (5): 467–476. doi:10.1111/cge.12986. PMID 28155232.

- Lidral, AC; Reising, BC (April 2002). "The role of MSX1 in human tooth agenesis". J. Dent. Res. 81 (4): 274–8. doi:10.1177/154405910208100410. PMC 2731714. PMID 12097313.

- Tallón-Walton, V; Manzanares-Céspedes, MC; Carvalho-Lobato, P; Valdivia-Gandur, I; Arte, S; Nieminen, P (2014). "Exclusion of PAX9 and MSX1 mutation in six families affected by tooth agenesis. A genetic study and literature review". Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 19 (3): e248-54. doi:10.4317/medoral.19173. PMC 4048113. PMID 24316698.

- Tsokos, Michael (2008). Forensic Pathology Reviews 5. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 281. ISBN 9781597451109.

- "Wisdom Teeth". American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. Retrieved 2019-11-19.

They come in between the ages of 17 and 25, a time of life that has been called the “Age of Wisdom.”

- Cooper, Rachele (February 5, 2007). "Why Do We Have Wisdom Teeth?". Scienceline.org. Archived from the original on 2016-05-03.

- von Cramon-Taubadel, Noreen (2011-12-06). "Global human mandibular variation reflects differences in agricultural and hunter-gatherer subsistence strategies". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (49): 19546–19551. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10819546V. doi:10.1073/pnas.1113050108. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3241821. PMID 22106280.

- "Magdalenian Girl is a woman and therefore has oldest recorded case of impacted wisdom teeth" (Press release). Field Museum of Natural History. March 7, 2006. Retrieved February 15, 2013.

- Juodzbalys, Gintaras; Daugela, Povilas (Apr–Jun 2013). "Mandibular Third Molar Impaction: Review of Literature and a Proposal of a Classification (review)". J Oral Maxillofac Res. 4 (2): e1. doi:10.5037/jomr.2013.4201. PMC 3886113. PMID 24422029.

- Marciani RD (2012). "Is there pathology associated with asymptomatic third molars (review)". J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 70 (Suppl 1): 15–19. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2012.04.025. PMID 22717377.

- Dodson TB (Sep 2012). "The management of the asymptomatic, disease-free wisdom tooth: removal versus retention. (review)". Atlas Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 20 (2): 169–76. doi:10.1016/j.cxom.2012.06.005. PMID 23021394.

- Newman MG, Takei HH, Klokkevold PR, Carranza FA (2012). Carranza's Clinical Periodontology. Elsevier Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4377-0416-7.

- Pogrel MA (2012). "What are the Risks of Operative Intervention (review)". J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 70 (Suppl 1): 33–36. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2012.04.029. PMID 22705215.

- Ghaeminia H (2013). "Coronectomy may be a way of managing impacted third molars (systematic review)". Evid Based Dent. 14 (2): 57–8. doi:10.1038/sj.ebd.6400939. PMID 23792405.

- "Wisdom tooth". Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1989. ISBN 0-19-861186-2.

- Aristotle (2015). The History of Animals. Translated by D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson. Aeterna Press. p. 49.

- "What teeth reveal about the lives of modern humans". Retrieved 2018-10-22.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wisdom teeth. |