Zarma language

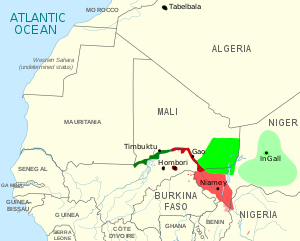

Zarma (also spelled Djerma, Dyabarma, Dyarma, Dyerma, Adzerma, Zabarma, Zarbarma, Zarma, Zarmaci or Zerma) is one of the Songhay languages. It is the leading indigenous language of the southwestern lobe of the West African nation of Niger, where the Niger River flows and the capital city, Niamey, is located. Zarma is the second-most common language in the country, after Hausa, which is spoken in south-central Niger. With over 2 million speakers, Zarma is easily the most widely spoken Songhay language.

| Zarma | |

|---|---|

| zarma ciine | |

| Region | southwestern Niger |

| Ethnicity | Zarma people |

Native speakers | 3.6 million (2016)[1] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | dje |

| Glottolog | zarm1239 Zarma-Kaado[2] |

| |

In earlier decades, Zarma was known as Djerma, and it is still sometimes called Zerma, especially among French-speakers, but it is usually now called Zarma, the name that its speakers use in their own language.

Orthography

The Zarma alphabet uses the following letters: a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, j, k, l, m, n, ɲ, ŋ, o, p, r, s, t, u, w, y, z. Nasal vowels are written with a tilde or a following ⟨n⟩ or ⟨ŋ⟩. Officially, the tilde should go under the vowel (so̰ho̰), but many current works write the tilde over the vowel (sõhõ).[4] Also, v may be used in a few words of foreign origin, but many Zarma cannot pronounce it.

Most of the letters are pronounced with the same values as the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), the exceptions being ⟨j⟩ [ɟ] (approximately English j but more palatalized), ⟨y⟩ [j], ⟨r⟩ [ɾ] (a flap). The letter ⟨c⟩ is approximately like English ch but more palatalized. The palatal nasal ⟨ɲ⟩ is spelled ⟨ny⟩ in older works.

Long consonants are written with double letters; ⟨rr⟩ is a trilled [r]. Long vowels are sometimes but inconsistently written with double letter. In older works, /c/ was spelled ⟨ky⟩ or ⟨ty⟩. Both ⟨n⟩ and ⟨m⟩ are pronounced as a labiodental nasal [ɱ] before ⟨f⟩.

Tone is not written unless the word is ambiguous. Then, the standard IPA diacritics are used: bá ("to be a lot": high tone), bà ("to share": low tone), bâ ("to want" or "even": falling tone) and bǎ ("to be better": rising tone). However, the meaning is almost always unambiguous in the context so the words are usually all written ba.

Phonology

Vowels

There are ten vowels: the five oral vowels (/a/, /e/, /i/, /o/, /u/) and their nasalized counterparts. There is slight variation, both allophonic and dialectal. Vowel length is phonemically distinctive. There are a number of combinations of a vowel with a semivowel /w/ or /j/, the semivowel being initial or final.

Consonants

| Labial | Dental | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | ||

| Stop | voiceless | p | t | c | k | |

| voiced | b | d | j /ɟ/ | g | ||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | h | ||

| voiced | z | |||||

| Approximant | w | l | y /j/ | |||

| Flap | r /ɾ/ | |||||

| Trill | rr /r/ | |||||

The combinations /ɡe/, /ɡi/, /ke/ and /ki/ usually have some palatal quality to them and may even be interchangeable with /ɟe/, /ɟi/, /ce/ and /ci/ in the speech of many people.

All consonants may be short, and all consonants except /c/, /h/, /f/ and /z/ may be long. (In some dialects, long /f/ exists in the word goffo.)

Lexical tone and stress

Zarma is a tonal language with four tones: high, low, fall and rise. In Dosso, some linguists (such as Tersis) have observed a dipping (falling-rising) tone for certain words: ma ("the name").

Stress is generally unimportant in Zarma. According to Abdou Hamani (1980), two-syllable words are stressed on their first syllable unless that syllable is just a short vowel: a-, i- or u-. Three-syllable words have stress on their second syllable. The first consonant of a stressed syllable is pronounced a bit more strongly, and the vowel in the preceding syllable is weakened. Only emphasized words have a stressed syllable. There is no change of tone for a stressed syllable.

Morphology

General

There are many suffixes in Zarma. There are very few prefixes, and only one (a-/i- before adjectives and numbers) is common.

Nouns

Nouns may be singular or plural. There are also three "forms" that indicate whether the noun is indefinite, definite or demonstrative. "Form" and number are indicated conjointly by an enclitic on the noun phrase. The singular definite enclitic is -ǒ or -ǎ. Some authors always write the ending with a rising tone mark even if it is not ambiguous and even if it is not truly a rising tone. The other endings are in the table below. The definite and the demonstrative endings replace any final vowel. See Hamani (1980) for a discussion on when to add -ǒ or -ǎ as well as other irregularities. See Tersis (1981) for a discussion of the complex changes in tone that may occur.

| Indefinite | Definite | Demonstrative | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | -∅ | -ǒ or -ǎ | -ô |

| Plural | -yáŋ | -ěy | -êy |

For example, súsúbày means "morning" (indefinite singular); súsúbǎ means "the morning" (definite singular); and súsúbô means "this morning" (demonstrative singular).

The indefinite plural -yáŋ ending is often used like English "some". Ay no leemuyaŋ means "Give me some oranges." Usually, the singular forms are used if the plurality is indicated by a number or other contextual clue, especially for the indefinite form: Soboro ga ba ("There are a lot of mosquitoes"); ay zanka hinkǎ ("my two children"); hasaraw hinko kulu ra ("in both of these catastrophes").

There is no gender or case in Zarma so the third-person singular pronoun a can mean "he", "she", "it", "her", "him", "his", "hers", "its", "one" or "one's", according to the context and its position in the sentence.

Verbs

Verbs do not have tenses and are not conjugated. There are at least three aspects for verbs that are indicated by a modal word before the verb and any object nouns. The aspects are the completive (daahir gasu), the incompletive (daahir gasu si) and the subjunctive (afiri ŋwaaray nufa). (Beginning grammars for foreigners sometimes inaccurately call the first two "past and present tenses".) There is also an imperative and a continuing or progressive construction. Lack of a modal marker indicates either the affirmative completive aspect (if there is a subject and no object) or the singular affirmative imperative (if there is no subject). There is a special modal marker, ka or ga, according to the dialect, to indicate the completive aspect with emphasis on the subject. Different markers are used to indicate a negative sentence.

| Affirmative | Negative | |

|---|---|---|

| Completive | ∅ or nà | mǎn or màná |

| Emphasized completive | ka or ga | mǎn or màná |

| Incompletive | ga | sí |

| Subjunctive | mà | mà sí |

| Progressive | go ga | si ga |

| Singular Imperative | ∅ | sí |

| Plural Imperative | wà | wà sí |

Linguists do not agree on the tone for ga. Some say that it is high before a low tone and low before a high tone.

There are several words in Zarma to translate the English "to be". The defective verb tí is used to equate two noun phrases, with the emphasized completive ka/ga, as in Ay ma ka ti Yakuba ("My name is Yakuba"). The existential gǒ (negative sí) is not a verb (White-Kaba, 1994, calls it a "verboid") and has no aspect; it means "exist" and usually links a noun phrase to a descriptive term, such as a place, a price or a participle: A go fuwo ra ("She's in the house"). The predicative nô means "it is", "they are", etc. and is one of the most common words in Zarma. It has no aspect or negative form and is placed after a noun phrase, sometimes for emphasis: Ni do no ay ga koy ("It's to your house I'm going"). Other words, such as gòró, cíyà, tíyà and bárà are much rarer and usually express ideas, such as the subjunctive, which gǒ and tí cannot handle.

Participles can be formed with the suffix -ànté, which is similar in meaning to the past participle in English. It can also be added to quantities to form ordinal numbers and to some nouns to form adjectives. A sort of gerund can be formed by adding -yàŋ, which transforms the verb into a noun. There are many other suffixes that can make nouns out of verbs, but only -yàŋ works with all verbs.

Two verbs can be related with the word ká. (In many dialects it is gá, not to be confused with the incompletive aspect marker or the emphasized completive marker.) The connector ká implies that the second verb is a result of the first or that the first is the reason or cause of the second: ka ga ŋwa, "come (in order to) eat." A large number of idiomatic expressions are expressed with it: sintin ga ... or sintin ka means "to begin to ...", ban ga ... means "to have already ...", ba ga ... means "to be about to ..., gay ga ... means "it's been awhile since ...", haw ga ... means "to purposely ..." and so on.

Syntax

Zarma's normal word order is subject–object–verb. The object is normally placed before the verb but may be placed after the verb for emphasis, and a few common verbs require the object after them. Unlike English, which places prepositions before a noun, Zarma has postpositions, which are placed after the noun: fuwo ra (in the house), fuwo jine (in front of the house).

When two nouns are placed together, the first noun modifies the second, showing possession, purpose or description: Fati tirǎ (Fati's book), haŋyaŋ hari (drinking water), fu meeyo (the door of a house). The same construction occurs with a pronoun before a noun: ni baaba ("your father"). All other modifiers of a noun (adjectives, articles, numbers, demonstratives etc.) are placed after the noun: Ay baaba wura muusu boŋey ("My father’s gold lion heads", Tersis, 1981).

Here is a proverb in Zarma:

Da curo fo hẽ, afo mana hẽ, i si jinde kaana bay.

da curo fo hẽ, a-fo mana hẽ, i si jinde kaan-a bay if bird one cry, noun-forming

prefix-onenegative.com-

pletive_aspectcry, they negative.incom-

pletive_aspectvoice good-definite know ‘If one bird sings, and another doesn't sing, they won't know which voice is sweetest".

That means that "you need to hear both sides of the story".

See also

References

- "Zarma". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2018-04-16.

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Zarma-Kaado". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- This map is based on classification from Glottolog and data from Ethnologue.

- Hamidou, Seydou Hanafiou (19 October 1999). "Arrêté n°0215/MEN/SP-CNRE du 19 octobre 1999 fixant l'orthographe de la langue soŋay-zarma" (PDF). Département de linguistique et des langues nationales, Institut de Recherches en Sciences Humaines, Université Abdou Moumouni de Niamey. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

Bibliography

- Bernard, Yves & White-Kaba, Mary. (1994) Dictionnaire zarma-français (République du Niger). Paris: Agence de coopération culturelle et technique

- Hamani, Abdou. (1980) La structure grammaticale du zarma: Essai de systématisation. 2 volumes. Université de Paris VII. Dissertation.

- Hamani, Abdou. (1982) De l’oralité à l’écriture: le zarma s’écrit aussi. Niamey: INDRAP

- Tersis, Nicole. (1981) Economie d’un système: unités et relations syntaxiques en zarma (Niger). Paris: SURUGUE.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Zarma phrasebook. |