Timucua

The Timucua were a Native American people who lived in Northeast and North Central Florida and southeast Georgia. They were the largest indigenous group in that area and consisted of about 35 chiefdoms, many leading thousands of people. The various groups of Timucua spoke several dialects of the Timucua language. At the time of European contact, Timucuan speakers occupied about 19,200 square miles (50,000 km2) in the present-day states of Florida and Georgia, with an estimated population of 200,000. Milanich notes that the population density calculated from those figures, 10.4 per square mile (4.0/km2) is close to the population densities calculated by other authors for the Bahamas and for Hispaniola at the time of first European contact.[1][2] The territory occupied by Timucua speakers stretched from the Altamaha River and Cumberland Island in present-day Georgia as far south as Lake George in central Florida, and from the Atlantic Ocean west to the Aucilla River in the Florida Panhandle, though it reached the Gulf of Mexico at no more than a couple of points.

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Extinct as a tribe | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Timucua | |

| Religion | |

| Native; Catholic | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Numerous internal chiefdoms, 11 dialects |

The name "Timucua" (recorded by the French as Thimogona but this is likely a misprint for Thimogoua) came from the exonym used by the Saturiwa (of what is now Jacksonville) to refer to the Utina, another group to the west of the St. Johns River. The Spanish came to use the term more broadly for other peoples in the area.[3] Eventually it became the common term for all peoples who spoke what is known as Timucuan.

While alliances and confederacies arose between the chiefdoms from time to time, the Timucua were never organized into a single political unit.[2] The various groups of Timucua speakers practiced several different cultural traditions.[4] The people suffered severely from the introduction of Eurasian infectious diseases, to which they had no immunity. By 1595, their population was estimated to have been reduced from 200,000 to 50,000 and thirteen chiefdoms remained. By 1700, the population of the tribe had been reduced to an estimated 1,000. Warfare against them by the English colonists and native allies, and the slave trade completed their extinction as a tribe soon after the turn of the 18th century.

Meaning

The word "Timucuan" may derive from "Thimogona" or "Tymangoua", an exonym used by the Saturiwa chiefdom of present-day Jacksonville for their enemies, the Utina, who lived inland along the St. Johns River. Both groups spoke dialects of the Timucua language. The French followed the Saturiwa in this usage, but the Spanish applied the term "Timucua" much more widely to groups within a wide section of interior North Florida.[3][5] In the 16th century they designated the area north of the Santa Fe River between the St. Johns and Suwannee Rivers (roughly the area of the group known as the Northern Utina) as the Timucua Province, which they incorporated into the mission system. The dialect spoken in that province became known as "Timucua" (now usually known as "Timucua proper").[6] During the 17th century, the Province of Timucua was extended to include the area between the Suwannee River and the Aucilla River, thus extending its scope.[7] Eventually, "Timucua" was applied to all speakers of the various dialects of the Timucua language.

History

The pre-Columbian era was marked by regular, routine, and probably small tribal wars with neighbors. The Timucua were organized into as many as 35 chiefdoms, each of which had hundreds of people in assorted villages within its purview. They sometimes formed loose political alliances, but did not operate as a single political unit.

An archaeological dig in St. Augustine in 2006 revealed a Timucuan site dating back to between 1100 and 1300 AD, predating the European founding of the city by more than two centuries. Included in the discovery were pottery, with pieces from the Macon, Georgia, area, indicating an expansive trade network; and two human skeletons. It is the oldest archaeological site in the city.[8]

The Timucua may have been the first American natives to see the landing of Juan Ponce de León near St. Augustine in 1513. This notion is up for debate since most historians now agree that the Ponce de León landing point was more likely much further south in Ais territory, near what is today Melbourne Beach. If so, Timucuan contact with that particular expedition was unlikely.[9][10] Later, in 1528, Pánfilo de Narváez's expedition passed along the western fringes of the Timucua territory.[4]

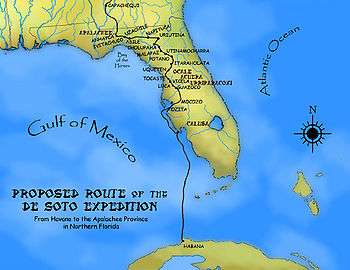

In 1539, Hernando de Soto led an army of more than 500 men through the western parts of Timucua territory, stopping in a series of villages of the Ocale, Potano, Northern Utina, and Yustaga branches of the Timucua on his way to the Apalachee domain (see list of sites and peoples visited by the Hernando de Soto Expedition for other sites visited by de Soto). His army seized the food stored in the villages, forced women into concubinage, and forced men and boys to serve as guides and bearers. The army fought two battles with Timucua groups, resulting in heavy Timucua casualties. De Soto was in a hurry to reach the Apalachee domain, where he expected to find gold and sufficient food to support his army through the winter, so he did not linger in Timucua territory.[4][11] The Acuera were one of the few Native American groups who bested the Spaniards in combat in the early part of the de Soto entrada,[12] though this is likely due to the fact that the full force accompanying Soto was not sent against Acuera as well as the expedition's relatively faster travel during this period.[13][14]

In 1564, French Huguenots led by René Goulaine de Laudonnière founded Fort Caroline in present-day Jacksonville and attempted to establish further settlements along the St. Johns River. After initial conflict, the Huguenots established friendly relations with the local natives in the area, primarily the Timucua under the cacique Saturiwa. Sketches of the Timucua drawn by Jacques le Moyne de Morgues, one of the French settlers, have proven valuable resources for modern ethnographers in understanding the people. The next year the Spanish under Pedro Menéndez de Avilés surprised the Huguenots and ransacked Fort Caroline, killing everyone but 50 women and children and 26 escapees. The rest of the French had been shipwrecked off the coast and picked up by the Spanish, who executed all but 20 of them; this brought French settlement in Florida to an end. These events caused a rift between the natives and Spanish, though Spanish missionaries were soon out in force.

The Timucua history changed after the Spanish established St. Augustine in 1565 as the capital of their province of Florida. From here, Spanish missionaries established missions in each main town of the Timucuan chiefdoms, including the Santa Isabel de Utinahica mission in what is now southern Georgia, for the Utinahica. By 1595, the Timucuan population had shrunk by 75%, primarily from epidemics of new infectious diseases introduced by contact with Europeans, and war.

By 1700, the Timucuan population had been reduced to just 1,000. In 1703 the British with the Creek, Catawba, and Yuchi began killing and enslaving hundreds of the Timucua.

A census in 1711 found 142 Timucua-speakers living in four villages under Spanish protection.[15] Another census in 1717 found 256 people in three villages where Timucua was the language of the majority, although there were a few inhabitants with a different native language.[16] The population of the Timucua villages was 167 in 1726.[17] By 1759 the Timucua under Spanish protection and control numbered just six adults and five half-Timucua children.[18]

In 1763, when Spain ceded Florida to Great Britain, the Spanish took the less than 100 Timucua and other natives to Cuba. Research is underway in Cuba to discover if any Timucua descendants exist there. Some historians believe a small group of Timucua may have stayed behind in Florida or Georgia and possibly assimilated into other groups such as the Seminoles. Many Timucua artifacts are stored at the Florida Museum of Natural History at the University of Florida and other museums.[19]

Tribes

The Timucua were divided into a number of different tribes or chiefdoms, each of which spoke one of the nine or ten dialects of the Timucua language. The tribes can be placed into eastern and western groups. The Eastern Timucua were located along the Atlantic coast and on the Sea Islands of northern Florida and southeastern Georgia; along the St. Johns River and its tributaries; and among the rivers, swamps and associated inland forests in southeastern Georgia, possibly including the Okefenokee Swamp. They usually lived in villages close to waterways, participated in the St. Johns culture or in unnamed cultures related to the Wilmington-Savannah culture, and were more focused on exploiting the resources of marine and wetland environments.[20] All of the known Eastern Timucua tribes were incorporated into the Spanish mission system starting in the late 16th century.[21] However, the Acuera appear to have maintained a "parallel" religious system, with traditional shamans practicing openly with numerous followers even at the height of missionization.[22] After the Timucuan Rebellion of 1656, the Acuera left the mission system and appear to have remained in their traditional territory, and to have maintained their traditional religious and cultural practices through the beginning of the eighteenth century.[23][24] They are the only known Timucuan chiefdom, among all the Timucua, to have done so.

List of Associated Tribes

- Acuera

- Alachua

- Cascangue

- Ibi

- Icafui

- Mocoso

- Ocale

- Potano

- Saturiwa

- Tacatacuru

- Tocobaga

- Utina

- Yufera

- Yustaga

The Western Timucua lived in the interior of the upper Florida peninsula, extending to the Aucilla River on the west and into Georgia to the north. They usually lived in villages in forests, and participated in the Alachua, Suwannee Valley or other unknown cultures. Because of their environment, they were more oriented to exploiting the resources of the forests.[20]

Earlier scholars such as John Swanton and John Goggin identified tribes around Tampa Bay – Tocobaga, the Uzita, and the Mocoso – as Timucua speakers, classed by Goggin as Southern Timucua. However, some of these tribes appear not to have spoken Timucua.[25]

Eastern Timucua

The largest and best known of the eastern Timucua groups were the Mocama, who lived in the coastal areas of what are now Florida and southeastern Georgia, from St. Simons Island to south of the mouth of the St. Johns River.[26] They gave their name to the Mocama Province, which became one of the major divisions of the Spanish mission system. They spoke a dialect also known as Mocama (Timucua for "Ocean"), which is the best attested of the Timucua dialects. At the time of European contact, there were two major chiefdoms among the Mocama, the Saturiwa and the Tacatacuru, each of which had a number of smaller villages subject to them.[27]

The Saturiwa were concentrated around the mouth of the St. Johns in what is now Jacksonville, and had their main village on the river's south bank.[28] European contact with the Eastern Timucua began in 1564 when the French Huguenots under René Goulaine de Laudonnière established Fort Caroline in Saturiwa territory. The Saturiwa forged an alliance with the French, and at first opposed the Spanish when they arrived. Over time, however, they submitted to the Spanish and were incorporated into their mission system. The important Mission San Juan del Puerto was established at their main village; it was here that Francisco Pareja undertook his studies of the Timucua language. The Tacatacuru lived on Cumberland Island in present-day Georgia, and controlled villages on the coast. They too were incorporated into the Spanish mission system, with Mission San Pedro de Mocama being established in 1587.

Other Eastern Timucua groups lived in southeastern Georgia. The Icafui and Cascangue tribes occupied the Georgia mainland north of the Satilla River, adjacent to the Guale. They spoke the Itafi dialect of Timucua. The Yufera tribe lived on the coast opposite to Cumberland Island and spoke the Yufera dialect. The Ibi tribe lived inland from the Yufera, and had 5 towns located 14 leagues (about 50 miles) from Cumberland Island; like the Icafui and Cascangue they spoke the Itafi dialect. All these groups participated in a culture that was intermediate between the St. Johns and Wilmington-Savannah cultures. The Oconi lived further west, perhaps on the east side of the Okefenokee Swamp. Both the Ibi and Oconi eventually received their own missions, while the coastal tribes were subject to San Pedro on Cumberland Island.

Up the St. Johns River to the south of the Saturiwa were the Utina, later known as the Agua Dulce or Agua Fresca (Freshwater) tribe. They lived along the river from roughly the Palatka area south to Lake George. They participated in the St. Johns culture and spoke the Agua Dulce dialect. The area between Palatka and downtown Jacksonville was relatively less populated, and may have served as a barrier between the Utina and Saturiwa, who were frequently at war. In the 1560s the Utina were a powerful chiefdom of over 40 villages. However, by the end of the century the confederacy had crumbled, with most of the diminished population withdrawing to six towns further south on the St. Johns.

The Acuera lived along the Ocklawaha River, and spoke the Acuera dialect. Unlike most of the other Timucuan chiefdoms, they maintained much of their traditional social structure during the mission period and are the only known Timucuan chiefdom to have missions in their territory for several decades, to have left the mission system, and to have remained in their original territory with much of their traditional culture and religious practices intact despite missionization.[14][29]

Western Timucua

Three major Western Timucua groups, the Potano, Northern Utina, and Yustaga, were incorporated into the Spanish mission system in the late 16th and 17th centuries.[30]

The Potano lived in north central Florida, in an area covering Alachua County and possibly extending west to Cofa at the mouth of the Suwannee River. They participated in the Alachua culture and spoke the Potano dialect. They were among the first Timucua peoples to encounter Europeans. They were frequently at war with the Utina tribe, who managed to convince first the French and later the Spanish to join them in combined assaults against the Potano. They received missionaries in the 1590s and five missions were built in their territory by 1633[31] . Like other Western Timucua groups they participated in the Timucua Rebellion of 1656.

North of the Potano, living in a wide area between the Suwannee and St. Johns Rivers, were the Northern Utina. This name is purely a convention; they were known as the "Timucua" to their contemporaries. They participated in the Suwannee Valley culture and spoke the "Timucua proper" dialect. The Northern Utina appear to have been less integrated than other Timucua tribes, and seem to have been organized into several small local chiefdoms, with the leader of one being recognized as paramount chief. They were missionized beginning in 1597 and their territory was organized by the Spanish as the Timucua Province. Over time smaller provinces were merged into the Timucua Province, thereby increasing the profile of the Northern Utina substantially. They took the forefront in the Timucua Rebellion of 1656, and their society declined severely when it was put down.

On the other side of the Suwannee River from the Northern Utina were the westernmost Timucua group, the Yustaga. They lived between the Suwannee and the Aucilla River, which served as a boundary with the Apalachee. They participated in the same Suwanee Valley culture as the Northern Utina, but appear to have spoken a different dialect, perhaps Potano. Unlike other Timucua groups, the Yustaga resisted Spanish missionary efforts until well into the 17th century. They maintained higher population levels significantly later than other Timucua groups, as their less frequent contact with Europeans kept them freer of introduced diseases. Like other Western Timucua groups, they participated in the Timucua Rebellion.

Other Western Timucua tribes are known from the earliest Spanish records, but later disappeared. The most significant of these are the Ocale, who lived in Marion County, near the modern city of Ocala, which takes its name from them. Ocale was conquered by De Soto in 1538 and the people dispersed; the town is unknown from later sources. However, both French and Spanish sources note a town named Eloquale or Etoquale in the Acuera chiefdom, suggesting that the Ocale may have migrated east and joined the Acuera. Hann has argued that the chiefdom of Mocoso, located near the mouth of the Alafia River on the eastern shore of Tampa Bay in the 16th century, was Timucuan. He suggests that the people of that chiefdom may have relocated to the village of Mocoso in Acuera province in the 17th century.[32]

Organization and classes

The Timucua were not a unified political unit. Rather, they were made up of at least 35 chiefdoms, each consisting of about two to ten villages, with one being primary.[2] In 1601 the Spanish noted more than 50 caciques (chiefs) subject to the head caciques of Santa Elena (Yustaga), San Pedro (Tacatacuru, on Cumberland Island), Timucua (Northern Utina) and Potano. The Tacatacuru, Saturiwa and Cascangue were subject to San Pedro, while the Yufera and Ibi, neighbors of the Tacatacuru and Cascangue, were independent.[33]

Villages were divided into family clans, usually bearing animal names. Children always belonged to their mother's clan.

Customs

The Timucua played two related but distinct ball games. Western Timucua played a game known as the "Apalachee ball game". Despite the name, it was as closely associated with the western Timucua as it was with the Apalachee. It involved two teams of around 40 or 50 players kicking a ball at a goal post. Hitting the post was worth one point, while landing it in an eagle's nest at the top of the post was worth two; the first team to score eleven points was the victor. The western Timucua game was evidently less associated with religious significance, violence, and fraud than the Apalachee version, and as such missionaries had a much more difficult time convincing them to give it up.[34][35]

The eastern Timucua played a similar game in which balls were thrown, rather than kicked, at a goal post. The Timucua probably also played chunkey, as did the neighboring Apalachee and Guale peoples, but there is no firm evidence of this. Archery, running, and dancing were other popular pastimes.[34]

The chief had a council that met every morning when they would discuss the problems of the chiefdom and smoke. To initiate the meeting, the White Drink ceremony would be carried out (see "Diet" below). The council members were among the more highly respected members of the tribe. They made decisions for the tribe.

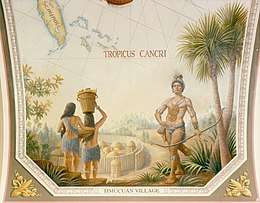

Settlements

The Timucua of northeast Florida (the Saturiwa and Agua Dulce tribes) at the time of first contact with Europeans lived in villages that typically contained about 30 houses, and 200 to 300 people. The houses were small, made of upright poles and circular in shape. Palm leaf thatching covered the pole frame, with a hole at the top for ventilation and smoke escape. The houses were 15 to 20 feet (4.5 to 6 m) across and were used primarily for sleeping. A village would also have a council house which would usually hold all of the villagers. Europeans described some council houses as being large enough to hold 3,000 people. If a village grew too large, some of the families would start a new village nearby, so that clusters of related villages formed. Each village or small cluster of related villages had its own chief. Temporary alliances between villages for warfare were also formed. Ceremonial mounds might be in or associated with a village, but the mounds belonged to clans rather than villages.[36]

Diet

The Timucua were a semi-agricultural people and ate foods native to North Central Florida. They planted maize (corn), beans, squash and various vegetables as part of their diet. Archaeologists' findings suggest that they may have employed crop rotation. In order to plant, they used fire to clear the fields of weeds and brush. They prepared the soil with various tools, such as the hoe. Later the women would plant the seeds using two sticks known as coa. They also cultivated tobacco. Their crops were stored in granaries to protect them from the insects and weather. Corn was ground into flour and used to make corn fritters.

In addition to agriculture, the Timucua men would hunt game (including alligators, manatees, and maybe even whales); fish in the many streams and lakes in the area; and collect freshwater and marine shellfish. The women gathered wild fruits, palm berries, acorns, and nuts; and baked bread made from the root koonti. Meat was cooked by boiling or over an open fire known as the barbacoa, the origin of the word "barbecue". Fish were filleted and dried or boiled. Broths were made from meat and nuts.

After the establishment of Spanish missions between 1595–1620, the Timucua were introduced to European foods, including barley, cabbage, chickens, cucumbers, figs, garbanzo beans, garlic, European grapes, European greens, hazelnuts, various herbs, lettuce, melons, oranges, peas, peaches, pigs, pomegranates, sugar cane, sweet potatoes, watermelons, and wheat. The native corn became a traded item and was exported to other Spanish colonies.

A black tea called "black drink" (or "white drink" because of its purifying effects) served a ceremonial purpose, and was a highly caffeinated Cassina tea, brewed from the leaves of the Yaupon Holly tree. The tea was consumed only by males in good status with the tribe. The drink was posited to have an effect of purification, and those who consumed it often vomited immediately. This drink was integral to most Timucua rituals and hunts.[37]

Physical appearance

Spanish explorers were shocked at the height of the Timucua, who averaged four inches or more above them. Timucuan men wore their hair in a bun on top of their heads, adding to the perception of height. Measurement of skeletons exhumed from beneath the floor of a presumed Northern Utina mission church (tentatively identified as San Martín de Timucua) at the Fig Springs mission site yielded a mean height of 64 inches (163 cm) for nine adult males and 62 inches (158 cm) for five adult women. The conditions of the bones and teeth indicated that the population of the mission had been chronically stressed.[38] Each person was extensively tattooed. The tattoos were gained by deeds. Children began to acquire tattoos as they took on more responsibility. The people of higher social class had more elaborate decorations. The tattoos were made by poking holes in the skin and rubbing ashes into the holes. The Timucua had dark skin, usually brown, and black hair. They wore clothes made from moss, and cloth created from various animal skins.

Language

The Timucua groups, never unified culturally or politically, are defined by their shared use of the Timucua language.[39] The language is relatively well attested compared to other Native American languages of the period. This is largely due to the work of Francisco Pareja, a Franciscan missionary at San Juan del Puerto, who in the 17th century produced a grammar of the language and four catechisms in parallel Timucua and Spanish. The other sources for the language are two catechisms by another Franciscan, Gregorio de Movilla, two letters from Timucua chiefs, and bits and pieces in other European sources.[40]

Pareja noted that there were ten dialects of Timucua, which were usually divided along tribal lines. These are Timucua proper, Potano, Itafi, Yufera, Mocama, Agua Salada, Tucururu, Agua Fresca, Acuera, and Oconi.[41]

Notes

- Milanich 1996, pp. 60-61

- Milanich 2000

- Milanich 1996, p. 46.

- Milanich 1998a

- ""Episode 03 Indian Canoes" by Robert Cassanello and Bob Clarke". stars.library.ucf.edu. Retrieved 2016-01-09.

- Milanich. 1978. 62.

- Weisman. 170.

- Clark, Jessica (June 2, 2006). "Dig Proves Historically Significant", First Coast News.

- Moody, Norman (April 21, 2011). "Naming barrier island would honor state find". Florida Today. Melbourne, Florida. pp. 1A.

- Datzman, Ken. "Did the famous explorer Ponce de León first hit Melbourne Beach", Brevard Business News, vol 30, no. 1 (Melbourne, Florida: January 02, 2012), p. 1 and 19.

- Hudson 1997

- The Florida of the Inca, by El Inca [Garcilaso de la Vega](1591), as translated by Varner (1951), pgs. 116-123.

- Boyer, Willet A., III (2010). The Acuera of the Oklawaha River Valley: Keepers of Time in the Land of the Waters (PDF) (dissertation). University of Florida. Retrieved 7 Dec 2017.

- Boyer, III, Willet. "The Hutto/Martin Site of Marion County, Florida, 8MR3447: Studies at an Early Contact/Mission Site". The Florida Anthropologist Volume 70(3:122-139) 2017. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) On-line as"The Hutto/Martin Site of Marion County, Florida, 8MR3447: Studies at an Early Contact/Mission Site". academia.edu. 7 December 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2017. - Hann. 1996. 304–305

- Hann. 1996. 308–311

- Hann. 1996. 317

- Hann. 1996. 323

- "The First Coast's 1st People: The Timucuan Indians, Jessica Clark, First Coast News, March 9, 2015".

- Milanich 1978. 59, 62.

Deagan. 92.

Hann 1996. 14-5.

Milanich. 1998b. 56. - Deagan. 95, 97-101

- Boyer 2010

- Boyer. 2009

- Boyer. 2010

- Granberry, p. 4; 11.

- Soergel, Matt (18 Oct 2009). "The Mocama: New name for an old people". The Florida Times-Union. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

- Ashley, p. 127.

- Deagan, pp. 95, 104, 108-9, 111.

- Boyer, Willet A., III (2010). The Acuera of the Oklawaha River Valley: Keepers of Time in the Land of the Waters (PDF) (dissertation). University of Florida. Retrieved 7 Dec 2017.

- Hann 1996. 9.

Milanich 1978. 62.

Milanich 1998b. 56. - Boyer, III, Willet (2015). "Potano in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries: New Excavations at the Richardson/UF Village Site, 8AL100". The Florida Anthropologist 2015 68(3-4). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) On-line as"Potano in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries: New Excavations at the Richardson/UF Village Site, 8AL100". academia.edu. 23 January 2016. Retrieved 23 January 2016. - Hann 2003. 6, 21, 24, 34-5, 105, 114, 117-8, 135

- Deagan. 91.

- Hann 1996, pp. 107–111.

- Bushnell:5, 13, 16-7

- Milanich 1998b. 44, 46-9.

- Hudson 1976

- Hoshower and Milanich. 217, 222, 234-5.

- Milanich 1999, pp. xvii–xviii.

- Granberry, pp. xv–xvii.

- Granberry, p. 6.

References

- Ashley, Keith H. (2009). "Straddling the Florida-Georgia State Line: Ceramic Chronology of the St. Marys Region (AD 1400–1700)". In Kathleen Deagan and David Hurst Thomas, From Santa Elena to St. Augustine: Indigenous Ceramic Variability (A.D. 1400-1700), pp. 125–139. New York : American Museum of Natural History

- Boyer, Willet A., III (2009). "Missions to the Acuera: An Analysis of the Historic and Archaeological Evidence for European Interaction With a Timucuan Chiefdom". The Florida Anthropologist. 62 (1–2): 45–56. ISSN 0015-3893. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- Boyer, Willet A., III (2010). The Acuera of the Oklawaha River Valley: Keepers of Time in the Land of the Waters (PDF) (dissertation). University of Florida. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- Boyer, Willet A. (2015). Boyer, III, Willet (2015). "Potano in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries: New Excavations at the Richardson/UF Village Site, 8AL100". The Florida Anthropologist 2015 68(3-4). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) On-line as"Potano in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries: New Excavations at the Richardson/UF Village Site, 8AL100". academia.edu. 23 January 2016. Retrieved 23 January 2016. - Boyer, Willet A. (2017). Boyer, III, Willet. "The Hutto/Martin Site of Marion County, Florida, 8MR3447: Studies at an Early Contact/Mission Site". The Florida Anthropologist Volume 70(3:122-139) 2017. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) On-line as"The Hutto/Martin Site of Marion County, Florida, 8MR3447: Studies at an Early Contact/Mission Site". academia.edu. 7 December 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2017. - Bushnell, Amy. (1978). "'That Demonic Game': The Campaign to Stop Indian Pelota Playing in Spanish America, 1675-1684." The Americas 35(1):1-19. Reprinted in David Hurst Thomas. (1991). Spanish Borderlands Sourcebooks 23 The Missions of Spanish Florida. Garland Publishing. ISBN 0-8240-2098-7

- Deagan, Kathleen A. (1978) "Cultures in Transition: Fusion and Assimilation among the Eastern Timucua." In Milanich and Procter.

- Hann, John H. (1996) A History of the Timucua Indians and Missions. University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1424-7

- Hann, John H. (2003) Indians of Central and South Florida: 1513-1763. University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-2645-8

- Hoshower, Lisa M. and Jerald T. Milanich. (1993) "Excavations in the Fig Springs Mission Burial Area." In McEwan 1993.

- Hudson, Charles M. (1976) The Southeastern Indians. University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 0-87049-248-9.

- Hudson, Charles M. (1997) Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun. University of Georgia Press.

- McEwan, Bonnie G. ed. (1993) The Spanish Missions of La Florida. University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1232-5

- McEwan, Bonnie G. ed. (2000) Indians of the Greater Southeast: Historical Archaeology and Ethnohistory. University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1778-5.

- Milanich, Jerald T. (1978) "The Western Timucua: Patterns of Acculturation and Change." In Milanich and Procter.

- Milanich, Jerald T. (1996) The Timucua. Blackwell Publications, Oxford, UK.

- Milanich, Jerald T. (1998a) Florida Indians and the Invasion from Europe. The University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1636-3.

- Milanich, Jerald T. (1998b) Florida Indians from Ancient Times to the Present. The University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1599-5.

- Milanich, Jerald (1999). The Timucua. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-21864-5. Retrieved August 9, 2010.

- Milanich, Jerald T. (2000) "The Timucua Indians of Northern Florida and Southern Georgia". in McEwan 2000.

- Milanich, Jerald T. (2004) "Timucua." In R. D. Fogelson (Ed.), Handbook of North American Indians: Southeast. (Vol. 17) (pp. 219–228) (W. C. Sturtevant, Gen. Ed.). Washington, D. C.: Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 0-16-072300-0.

- Milanich, Jerald T. and Samuel Procter, Eds. (1978) Tacachale: Essays on the Indians of Florida and Southeastern Georgia during the Historic Period. The University Presses of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-0535-3

- Mooney, James. (1910) Timucua. Bureau of American Ethnology, bulletin (No. 30.2, p. 752).

- Swanton, John R. (1946) The Indians of the southeastern United States. Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology bulletin (No. 137). Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

- Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve

- Worth, John. (1998) The Timucuan Chiefdoms of Spanish Florida: Volume I: Assimilation, Volume II: Resistance and Destruction. University of Florida Press.

- Weisman, Brent R. (1993) "Archaeology of Fig Springs Mission, Ichetucknee Springs State Park", in McEwan 1993.

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Timucua. |