Xian H-6

H-6 (Chinese: 轰-6; pinyin: Hōng-6) is a licence-built[1] version of the Soviet Tupolev Tu-16 twin-engine jet bomber, built for China's People's Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF).

| H-6 Bomber | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| H-6 landing at Zhuhai Jinwan Airport | |

| Role | Strategic bomber |

| National origin | China |

| Manufacturer | Xi'an Aircraft Industrial Corporation |

| Designer | Harbin |

| First flight | 1959[1] |

| Introduction | 1969[2] |

| Retired | Iraq (1991) Egypt (2000) |

| Status | Active service with the Chinese Air Force |

| Primary users | People's Liberation Army Air Force People's Liberation Army Navy Egyptian Air Force (historical) Iraqi Air Force (historical) |

| Number built | 162–180[1] |

| Developed from | Tupolev Tu-16 |

| Variants | Xian H-6I |

Delivery of the Tu-16 to China began in 1958, and the Xi'an Aircraft Industrial Corporation (XAC) signed a licence production agreement with the USSR to build the type in the late 1950s. The first Chinese Tu-16, or "H-6" as it was designated in Chinese service, flew in 1959. Production was performed by the plant at Xian, with at least 150 built into the 1990s. China is estimated to currently operate around 120 of the aircraft.[3]

The latest version is the H-6N, a heavily redesigned version capable of aerial refueling and carrying air-launched cruise missiles. According to United States Department of Defense, this will give the Chinese Air Force a long-range standoff offensive air capability with precision-guided munitions.[4][5]

Design and development

The first domestically produced H-6 was completed in 1968[3] and evidence of bombing training was recorded by U.S. spy satellites on August 13, 1971.[3] By March of the following year, the CIA estimated that the PRC had 32 aircraft operational with an additional 19 awaiting completion.[3]

The H-6 was used to drop nine nuclear devices at the Lop Nur test site. However, with the increased development in ballistic missile technology, the nuclear delivery capabilities that the H-6 offered diminished in importance. The CIA estimated in 1976 that the H-6 had moved over to a dual nuclear/conventional bombing role.

Developed versions

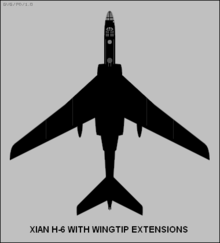

Along with the H-6 free-fall bomber, an "H-6A" nuclear bomber was built, as well as an "H-6B" reconnaissance variant, "H-6C" conventional bomber and "H-6E" nuclear bomber with improved countermeasures, the "H-6D" antiship missile carrier, and the "HY-6" series capable of acting as an in-flight fuel tanker. The H-6D was introduced in the early 1980s and carried a C-601 antishipping missile (NATO codename "Silkworm"), an air-launched derivative of the Soviet P-15 Termit ("Styx") under each wing. The H-6D featured various modernized systems and sports an enlarged radome with a Type 245 Kobalt I-band surveillance radar under the nose. The Type 245 radar was based on the Soviet PSBN-M-8 NATO codename Mushroom radar used on the Tupolev Tu-16. Earlier versions (Type 241, 242 and 244) were installed on the early models of the H-6. The H-6 has also been used as a tanker and drone launcher. Later H-6 production featured extended curved wingtips.[1]

Many H-6A and H-6C aircraft were updated in the 1990s to the "H-6F" configuration, the main improvement being a modern navigation system, with a Global Positioning System (GPS) satellite constellation receiver, Doppler navigation radar, and inertial navigation system. New production began in the 1990s as well, with Xian building the "H-6G", which is a director for ground-launched cruise missiles; the "H-6H", which carries two land-attack cruise missiles. In terms of land attack cruise missiles five immediate possibilities were considered by PLAAF - the indigenous HN-1, HN-2 and HN-3, DH-10/CJ-10, and a variant of Russian designed cruise missile. It is believed CJ-10 is chosen to be the main land attack missile for H-6 bombers,[6] and now the "H-6M" cruise missile carrier, which has four pylons for improved cruise missiles and is fitted with a terrain-following system. Apparently these variants have no internal bomb capability, and most or all of their defensive armament has been deleted.

H-6K

The H-6K, first flying on January 5, 2007,[7] entered service in October 2009 during the celebrations of the 60th anniversary of the People's Republic of China,[8] and is claimed to make China the fourth country with a strategic bomber after US, Russia and the United Kingdom.[8][9] With a reinforced structure making use of composite materials,[9] enlarged engine inlets for Russian Soloviev D-30 turbofan engines giving a claimed combat radius of 3,500 kilometres (2,200 mi),[8] a glass cockpit with large size LCD multi-function display,[10] and a reworked nose section eliminating the glazed navigator's station in favour of a more powerful radar, the H-6K is a significantly more modern aircraft than earlier versions. Six underwing hardpoints for CJ-10A cruise missiles are added. The rear 23 mm guns and gunner position are replaced by electronic components.[10]

The H-6K is designed for long-range attacks and stand-off attacks. It is capable of attacking US carrier battle groups and priority targets in Asia. This aircraft has nuclear strike capability.[11] While previous models had limited missile capacity (the H-6G could only carry two YJ-12 anti-ship missiles and the H-6M two KD-20/CJ-10K/CJ-20 land attack cruise missiles), the H-6K can carry up to six YJ-12 and 6-7 ALCMs; a single regiment of 18 H-6Ks fully loaded out with YJ-12s can saturate enemy ships with over 100 supersonic missiles. Although the aircraft has a new nose radome housing a modern air-to-ground radar, it is not clear if the bomber or other Chinese assets yet have the capability to collect accurate targeting information for successful strikes against point targets in areas beyond the first island chain.[12][13][14] An electro-optical targeting system is fitted under the nose.[15]

In January 2009, it was reported that an indigenous turbofan engine, the WS-18 (Soloviev D-30 copy), was under development for use in the H-6K.[16]

In 2015, about 15 H-6Ks were in service.[17]

A H-6K fitted with a refuelling probe may have first flown in December 2016. Besides extending range, a possible mission for the variant may be to launch satellites or ballistic missiles.[18]

Defense Intelligence Agency chief Ashley confirmed that China is developing two new air-launched ballistic missiles, (CH-AS-X-13)[19] one of which can carry a nuclear warhead.[20][21] The H-6K would be suited to launch such missiles.

In January 2019, Norinco announced it had tested an analogous of the American "Mother of all Bombs." The weapon is carried by an H-6K and takes up the whole of the bomb bay, making it roughly 5–6 m (16–20 ft) long and weighing 10 tons. Chinese media claimed it could be used for wiping out reinforced buildings and shelters as well as clearing obstacles to create an aircraft landing zone.[22][23][24]

Operational history

China has repeatedly used H-6 aircraft to perform long-range drills near Japan, prompting the Japanese Air Self-Defense Force to scramble fighters.[25][26][27]

Variants

Production versions

- Xian H-6 – Conventional bomber. Tupolev Tu-16 produced under license in China, first flew in 1959.[1] A prototype conducted China’s first aerial nuclear weapon test at Lop Nor on 14 May 1965.

- Xian H-6A – Nuclear bomber.[1]

- Xian H-6B – Aerial reconnaissance variant.[1]

- Xian H-6C – Conventional bomber with improved counter-measures suite.[1] Initially designated H-6III.

- Xian H-6D – Anti-ship missile carrier introduced in early 1980s, armed with two air-launched C-601 missiles, one mounted under each wing. Fitted with larger radome under the nose and various improved systems.[1]

- Later upgraded to either two C-301 supersonic anti-ship missiles, or four C-101 supersonic anti-ship missiles. An upgraded version, capable of carrying four YJ-8 (C-801) anti-ship missiles is currently under development.[7] Initially designated H-6IV.

- Xian H-6E – Strategic nuclear bomber with improved counter-measures suite,[1] entered service in 1980s.

- Xian H-6F – New designation for upgraded H-6A and H-6C. Many aircraft upgraded in the 1990s with new inertial navigation systems, doppler navigation radar and GPS receiver.[1]

- Xian H-6G – Provides targeting data to ground-launched cruise missiles, built in the 1990s. No internal bomb bay or defensive armament.[1] Electronic-warfare aircraft with underwing electronic countermeasures pods.[28]

- Xian H-6H – Land-attack cruise missile carrier armed with two missiles, built in the 1990s. No internal bomb bay or defensive armament.[1]

- Xian H-6K – Latest H-6 variant, re-engined with D-30KP turbofan engines of 12,000 kg thrust replacing the original Chinese turbojets. Other modifications include larger air intakes, re-designed flight deck with smaller/fewer transparencies and large dielectric nose radome.

- Xian H-6J – Version of H-6K for use by the People’s Liberation Army Navy Air Force (PLANAF) to replace the H-6G; has greater payload and range with performance similar to H-6K.[29]

- Xian H-6M – Cruise missile carrier, fitted with terrain-following system and four under-wing hardpoints for weapons carriage. No internal bomb bay or defensive armament.[1] Production of this variant is believed to have resumed in early 2006.[30]

- Xian H-6N/H-6X1 – Air-launched ballistic missile carrier in service as of 2019.[31][32][33] This variant has a semi-recessed area hard point underneath its fuselage. It is capable of mounting an air-derivative of the Dongfeng-21D anti-ship ballistic missile or the CJ-100 supersonic cruise missile,[34][35] with an added 3,700 mile range including aerial refueling or a variety of other oversized payloads - including those with nuclear warheads.[36] It may be also possible that the modification is to enable carriage of the WZ-8 high-speed, high-altitude reconnaissance unmanned aerial vehicle.[37]

- Xian HD-6 (Hongzhaji Dian-6) – Electronic warfare version with solid nose and canoe fairing believed to contain electronic counter-measures equipment.

Aerial refuelling versions

- Xian HY-6 (Hongzhaji You-6) – First successful in-flight refuelling tanker variant in Chinese service. Retained PV-23 fire control system of H-6 and thus can still be deployed as a missile launcher.

- Xian HY-6U – Modified HY-6 tanker in service with the PLAAF, with PV-23 fire control system and Type 244 radar deleted, and thus a dedicated refueling aircraft[38] Also referred as H-6U

- Xian HY-6D – First aerial refueling tanker for PLANAF, converted from H-6D. The most distinct difference between HY-6U and HY-6D is that HY-6U has a metal nose cone, while HY-6D still has the transparent class nose. Like the original HY-6, PV-23 fire control system is also retained on HY-6D, which enables the aircraft also to serve as a missile carrying and launching platform.

- Xian HY-6DU – Aerial refuelling tanker for the PLANAF, modified HY-6D, also referred as H-6DU. Similar to HY-6U, HY-6DU is a dedicated aerial refueling tanker when its PV-23 fire control system is removed from the aircraft.

Export versions

- Xian B-6D – Export version of the H-6D.

Testbeds, prototypes and proposed variants

- Xian H-6I – Modified version powered by four Rolls-Royce Spey Mk 512 turbofan engines, originally purchased as spare engines for Hawker Siddeley Tridents in service with CAAC. Modifications included a lengthened fuselage and smaller engine nacelles with smaller air intakes in the wing roots, where the original two turbojet engines were replaced with two Spey turbofans. Two more Spey engines mounted on pylons, one under each wing, outboard of the undercarriage sponsons. Ferry range increased to 8,100 km (with standard payload), and combat radius increased to over 5,000 km (with nuclear payload). Development began in 1970, maiden flight took place in 1978 and state certification received in the following year.

- H-6 Engine Testbed – One H-6, serial number # 086, was converted into an engine testbed. Remained in service for 20 years until replacement by a converted Ilyushin Il-76.

- H-6 Launch Vehicle – Proposed variant intended to launch a 13 tonne Satellite Launch Vehicle at an altitude of 10,000 m. In 2000 preliminary studies began on the air-launched, all solid propellant SLV, capable of placing a payload of 50 kg in earth orbit. Mock-up of the SLV and H-6 launch platform shown during 2006 Zhuhai Air Show.

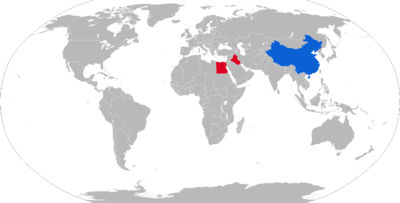

Operators

Current operators

- People's Liberation Army Air Force - 140 H-6/H-6E/H-6F/H-6H/H-6K, and 10 H-6U in service in 2014[39]

- People's Liberation Army Navy - 30 H-6D in service in 2010[40]

Former operators

- Egyptian Air Force — "Some" B-6 acquired post-1973 along with spares for the Egyptian Tu-16 fleet. Last aircraft retired in 2000.[1]

- Iraqi Air Force — Four H-6D, armed with C-601 missiles, acquired during Iran–Iraq War, during which one of them was downed. All remaining ones were destroyed in the Persian Gulf War of 1991.[1]

Specifications (H-6)

Data from Sinodefence.com[7]

General characteristics

- Crew: 4

- Length: 34.8 m (114 ft 2 in)

- Wingspan: 33 m (108 ft 3 in)

- Height: 10.36 m (34 ft 0 in)

- Wing area: 165 m2 (1,780 sq ft)

- Airfoil: root: PR-1-10S-9 (15.7%) ; tip: PR-1-10S-9 (12%)[41]

- Empty weight: 37,200 kg (82,012 lb)

- Gross weight: 76,000 kg (167,551 lb)

- Max takeoff weight: 79,000 kg (174,165 lb)

- Powerplant: 2 × Xian WP-8 turbojet engines, 93.2 kN (21,000 lbf) thrust each

Performance

- Maximum speed: 1,050 km/h (650 mph, 570 kn)

- Cruise speed: 768 km/h (477 mph, 415 kn) / 0.75M

- Range: 6,000 km (3,700 mi, 3,200 nmi)

- Combat range: 1,800 km (1,100 mi, 970 nmi)

- Service ceiling: 12,800 m (42,000 ft)

- Wing loading: 460 kg/m2 (94 lb/sq ft)

- Thrust/weight: 0.24

Armament

- Guns:

- 2× 23 mm (0.906 in) Nudelman-Rikhter NR-23 cannons in remote dorsal turret

- 2× NR-23 cannons in remote ventral turret

- 2× NR-23 cannons in manned tail turret

- 1× NR-23 cannons in nose (occasional addition)

- Missiles:

- 6 or 7 KD-88 missile (anti-ship or air-to-surface)

- YJ-100 (CJ-10) anti-ship missile

- C-601 anti-ship missile

- YJ-62 (C-602) anti-ship missile

- C-301 anti-ship missile

- C-101 anti-ship missile

- CM-802A

- YJ-12 anti-ship missile

- DF-21D (H-6N)

- Bombs: 9,000 kg (20,000 lb) of free-fall weapons

- Guided bombs

- GB6

- CS/BBC5

- GB2A

- GB5

- Guided bombs

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

References

- Notes

- "Reconnaissance & Special-Mission Tu-16s / Xian H-6". Air Vector. Archived from the original on 2017-04-22. Retrieved 2015-04-07.

- Aviation Museum, Northwestern Polytechnical University. "馆藏飞机介绍:轰-6-航空学院". hangkong.nwpu.edu.cn. Archived from the original on 26 October 2018. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- Chinese Nuclear Forces and US Nuclear War Planning (PDF), The Federation of American Scientists & The Natural Resources Defense Council, 2006, pp. 93–4, archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-04-28, retrieved 2007-02-03.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-05-14. Retrieved 2015-06-08.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- https://www.flightglobal.com/news/articles/china-shows-off-h-6n-hypersonics-and-gyrocopters-461186/

- "H-6H Cuirse Missile Bomber PLAAF". AirForceWorld.com. Archived from the original on 3 March 2015. Retrieved 2 April 2011.

- "H-6 Medium Bomber". Sinodefence.com. 2005-11-26. Archived from the original on 2012-06-17. Retrieved 2007-01-16.

- Kashin, Vasiliy (2009-12-11). "Strategic Cruise Missile Carrier H-6K – A New Era for Chinese Air Force". Moscow Defense Brief. Centre for Analysis of Strategies and Technologies. 4 (18). Archived from the original on December 29, 2009. Retrieved 2009-12-30.

- Chang, Andrei (2007-11-08). "Analysis: China attains nuclear strategic strike capability". United Press International. Archived from the original on July 28, 2011. Retrieved 2009-12-30.

- "H-6K Cruise Missile Bomber PLAAF". AirForceWorld.com. Archived from the original on 3 March 2011. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- ARG. "H-6K Long-Range Strategic Bomber - Military-Today.com". www.military-today.com. Archived from the original on 18 March 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- Jeffrey Lin and P.W. Singer, "China Shows Off Its Deadly New Cruise Missiles" Archived 2016-08-02 at the Wayback Machine, Popular Science, 10 March 2015

- The H-6K Is China’s B-52 Archived 2016-09-07 at the Wayback Machine - Warisboring.com, 8 July 2015

- Fisher, Richard D., Jr. (4 September 2015). "China showcases new weapon systems at 3 September parade". IHS Jane's 360. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- Richard d. Fisher, Jr (2008-09-30). China's Military Modernization: Building for Regional and Global Reach: Building for Regional and Global Reach. ISBN 9781567207613.

- "China Defense Mashup - SEO Reviews". www.china-defense-mashup.com. Archived from the original on 8 March 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- Diplomat, Franz-Stefan Gady, The. "China Wants to Develop a New Long-Range Strategic Bomber". thediplomat.com. Archived from the original on 2 December 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- "Chinese Xian H-6K with refuelling probe suggests new missions - Jane's 360". www.janes.com. Archived from the original on 24 February 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2018-11-13. Retrieved 2018-11-13.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Pentagon official's warning on weapons". news.com.au. Archived from the original on 7 March 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- "DIA: China, Russia Engaged In Low-Level Warfare Against U.S." freebeacon.com. 7 March 2018. Archived from the original on 7 March 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- CHINA DROPS ITS OWN 'MOTHER OF ALL BOMBS,' REPORTS SAY Archived 2019-01-07 at the Wayback Machine. Newsweek. 3 January 2019.

- China is showing off its homemade version of America's 'Mother of All Bombs' Archived 2019-01-07 at the Wayback Machine. Business Insider. 3 January 2019.

- China showcases own version of ‘Mother of All Bombs’ Archived 2019-01-05 at the Wayback Machine. Global Times.cn. 3 January 2019.

- Johnson, Jesse (November 26, 2016). "China again sends fighter jets, bombers through sensitive strait south of Okinawa". Japan Times. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved November 20, 2017.

- Johnson, Jesse Japan scrambles fighters as Chinese bombers transit Tsushima Strait for first time since August January 9, 2017 Archived September 25, 2017, at the Wayback Machine Japan Times Retrieved September 25, 2017

- Johnson, Jesse Chinese Air force conducts ‘several’ long-range drills near Japan as military tells Tokyo to ‘get used to it’ July 16, 2017 Archived September 25, 2017, at the Wayback Machine Japan Times Retrieved September 25, 2017

- "PLA retrofits old bombers as electronic warfare aircraft". atimes.com. Archived from the original on 2 March 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- China’s Navy Deploys New H-6J Anti-Ship Cruise Missile-Carrying Bombers Archived 2018-10-25 at the Wayback Machine. The Diplomat. 12 October 2018.

- Isby, David C. (2006-09-29). "Chinese H-6 bomber carries 'improved missiles'". Jane's Missiles and Rockets. Jane's Information Group. Archived from the original on 2006-11-30. Retrieved 2007-01-16.

- https://www.janes.com/article/90994/images-confirm-h-6n-bomber-variant-is-in-plaaf-service

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2018-11-13. Retrieved 2018-11-14.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2018-09-19. Retrieved 2018-11-14.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- https://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/29975/new-photos-point-to-chinese-bomber-being-able-to-carry-huge-anti-ship-ballistic-missiles

- https://sputniknews.com/asia/201911121077283651-supersonic-arsenal-may-expand-chinese-h-6n-bombers-range-to-6000-kilometers/

- https://www.popsci.com/explaining-chinas-big-bomber-plans#page-3

- https://www.janes.com/article/91701/images-suggest-wz-8-uav-in-service-with-china-s-eastern-theatre-command

- "H-6 Tanker". Sinodefence.com. 2006-05-27. Archived from the original on January 15, 2007. Retrieved 2007-01-16.

- IISS 2010: 404

- IISS 2010: 402

- Lednicer, David. "The Incomplete Guide to Airfoil Usage". m-selig.ae.illinois.edu. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- Bibliography

- International Institute for Strategic Studies (2010). Hacket, James (ed.). The Military Balance 2010. Oxfordshire: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-85743-557-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to |

- H-6 Bomber Family, AirForceWorld.com

- H-6 Medium Bomber, Sinodefence.Com

- Xian H-6 Badger, Ausairpower.Net

- https://web.archive.org/web/20091003131001/http://www.centurychina.com/plaboard/archive/3789340.shtml

- http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/china/h-8.htm

- http://www.mnd.gov.tw/English/publish.aspx?cnid=498&p=19940