Writhe

In knot theory, there are several competing notions of the quantity writhe, or Wr. In one sense, it is purely a property of an oriented link diagram and assumes integer values. In another sense, it is a quantity that describes the amount of "coiling" of a mathematical knot (or any closed simple curve) in three-dimensional space and assumes real numbers as values. In both cases, writhe is a geometric quantity, meaning that while deforming a curve (or diagram) in such a way that does not change its topology, one may still change its writhe.[1]

Writhe of link diagrams

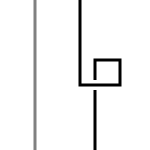

In knot theory, the writhe is a property of an oriented link diagram. The writhe is the total number of positive crossings minus the total number of negative crossings.

A direction is assigned to the link at a point in each component and this direction is followed all the way around each component. If as you travel along a link component and cross over a crossing, the strand underneath goes from right to left, the crossing is positive; if the lower strand goes from left to right, the crossing is negative. One way of remembering this is to use a variation of the right-hand rule.

|

| |

| Positive crossing | Negative crossing |

For a knot diagram, using the right-hand rule with either orientation gives the same result, so the writhe is well-defined on unoriented knot diagrams.

The writhe of a knot is unaffected by two of the three Reidemeister moves: moves of Type II and Type III do not affect the writhe. Reidemeister move Type I, however, increases or decreases the writhe by 1. This implies that the writhe of a knot is not an isotopy invariant of the knot itself — only the diagram. By a series of Type I moves one can set the writhe of a diagram for a given knot to be any integer at all.

Writhe of a closed curve

Writhe is also a property of a knot represented as a curve in three-dimensional space. Strictly speaking, a knot is such a curve, defined mathematically as an embedding of a circle in three-dimensional Euclidean space, R3. By viewing the curve from different vantage points, one can obtain different projections and draw the corresponding knot diagrams. Its Wr (in the space curve sense) is equal to the average of the integral writhe values obtained from the projections from all vantage points.[2] Hence, writhe in this situation can take on any real number as a possible value.[1]

We can calculate Wr with an integral. Let be a smooth, simple, closed curve and let and be points on . Then the writhe is equal to the Gauss integral

- .

Numerically approximating the Gauss integral for writhe of a curve in space

Since writhe for a curve in space is defined as a double integral, we can approximate its value numerically by first representing our curve as a finite chain of line segments. A procedure that was first derived by Levitt [3] for the description of protein folding and later used for supercoiled DNA by Klenin and Langowski [4] is to compute

where is the exact evaluation of the double integral over line segments and ; note that and .[4]

To evaluate for given segments numbered and , number the endpoints of the two segments 1, 2, 3, and 4. Let be the vector that begins at endpoint and ends at endpoint . Define the following quantities:[4]

Then we calculate[4]

Finally, we compensate for the possible sign difference and divide by to obtain[4]

In addition, other methods to calculate writhe can be fully described mathematically and algorithmically.[4]

Applications in DNA topology

DNA will coil if you twist it, just like a rubber hose or a rope will, and that is why biomathematicians use the quantity of writhe to describe the amount a piece of DNA is deformed as a result of this torsional stress. In general, this phenomenon of forming coils due to writhe is referred to as DNA supercoiling and is quite commonplace, and in fact in most organisms DNA is negatively supercoiled.[1]

Any elastic rod, not just DNA, relieves torsional stress by coiling, an action which simultaneously untwists and bends the rod. F. Brock Fuller shows mathematically[5] how the “elastic energy due to local twisting of the rod may be reduced if the central curve of the rod forms coils that increase its writhing number”.

References

- Bates, Andrew (2005). DNA Topology. Oxford University Press. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-0198506553.

- Cimasoni, David (2001). "Computing the Writhe of a Knot". Journal of Knot Theory and its Ramifications. 10 (387): 387–395. arXiv:math/0406148. doi:10.1142/S0218216501000913.

- Levitt, M (1986). "Protein Folding by Restrained Energy Minimization and Molecular Dynamics". J. Mol. Biol. 170 (3): 723–764. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.26.3656. doi:10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80129-6.

- Klenin, K; Langowski, J (2000). "Computation of writhe in modeling of supercoiled DNA". Biopolymers. 54 (5): 307–317. doi:10.1002/1097-0282(20001015)54:5<307::aid-bip20>3.0.co;2-y.

- Fuller, F B (1971). "The writhing number of a space curve". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 68 (4): 815–819. doi:10.1073/pnas.68.4.815. PMC 389050. PMID 5279522.

Further reading

- Adams, Colin (2004), The Knot Book: An Elementary Introduction to the Mathematical Theory of Knots, American Mathematical Society, ISBN 978-0-8218-3678-1