Wiscasset, Maine

Wiscasset is a town in and the seat of Lincoln County, Maine, United States.[4] The municipality is located in the state of Maine's Mid Coast region. The population was 3,732 as of the 2010 census. Home to the Chewonki Foundation, Wiscasset is a tourist destination noted for early architecture.

Wiscasset, Maine | |

|---|---|

Village square c. 1910 | |

Seal | |

| Motto(s): Maine's Prettiest Village | |

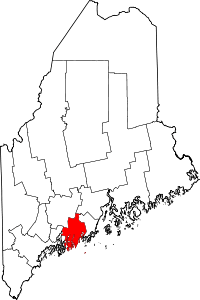

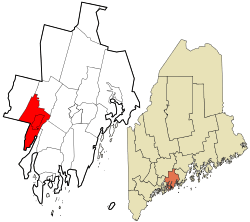

Location in Lincoln County and the state of Maine. | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Maine |

| County | Lincoln County |

| Settled | 1660 |

| Incorporated as Pownalborough | February 13, 1760 |

| Incorporated as Wiscasset | 1802 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Town Manager - Board of Selectmen |

| • Town Manager | Dennis Simmons |

| Area | |

| • Total | 27.66 sq mi (71.64 km2) |

| • Land | 24.63 sq mi (63.79 km2) |

| • Water | 3.03 sq mi (7.85 km2) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 3,732 |

| • Estimate (2012[3]) | 3,685 |

| • Density | 151.5/sq mi (58.5/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (Eastern) |

| ZIP code | 04578 |

| Area code(s) | 207 |

| Website | wiscasset.org |

The town is home to the Red's Eats restaurant.

History

In 1605, Samuel de Champlain is said to have landed here and exchanged gifts with the Indians. Situated on the tidal Sheepscot River, Wiscasset was first settled in 1660. The community was abandoned during the French and Indian Wars, and the King Philip's War in 1675 and then resettled around 1730. In 1760, it was incorporated as Pownalborough after Colonial Governor Thomas Pownall. In 1802, it resumed its original Abenaki name, Wiscasset, which means "coming out from the harbor but you don't see where."[5]

During the Revolutionary War, the British warship Rainbow harbored itself in Wiscasset Harbor and held the town at bay until the town gave the warship essential supplies.

In 1775, Captain Jack Bunker supposedly robbed the payroll of a British supply ship, Falmouth Packet, that was stowed in Wiscasset Harbor. He was chased for days and caught on Little Seal Island. His treasure reportedly has never been found.

Because of the siege during the Revolutionary War, Fort Edgecomb was built in 1808 on the opposite bank of the Sheepscot to protect the town harbor. Wiscasset's prosperity left behind fine early architecture, particularly in the Federal style when the seaport was important in privateering. Two dwellings of the period, Castle Tucker and the Nickels-Sortwell House, are now museums operated by Historic New England.

The seaport became a center for shipbuilding, fishing and lumber. Wiscasset quickly became the busiest seaport north of Boston until the embargo of 1807 halted much trade with England. Most of Wiscasset's business and trade was destroyed.[5]

Maine was officially admitted as a state in 1820 with the passage of the Maine-Missouri Compromise. The town of Wiscasset was considered for the state capital, but lost the position because of its proximity to the ocean.

During the Civil War, Wiscasset had many of its residents that joined the 20th Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiment. Its regiment was commended for fighting bravely at the Battle of Gettysburg.

Rail service to Wiscasset began with the Knox and Lincoln Railroad in 1871.[6] The Knox and Lincoln was merged into the Maine Central Railroad in 1901. Wiscasset was connected to the national rail network by the completion of the Carlton bridge over the Kennebec River in 1927.[7]

Wiscasset was the seaport terminal and standard gauge interchange of the 2-foot gauge Wiscasset, Waterville and Farmington Railway. Construction began in Wiscasset in 1894. Train service began in 1895 as the Wiscasset and Quebec Railroad. By 1913, the railroad operated daily freight and passenger service 43.5 miles north to Albion with an 11-mile freight branch from Weeks Mills to North Vassalboro.

Passengers and freight increasingly used highway transportation after World War I. Frank Winter bought the railroad about 1930 to move lumber from Branch Mills to his schooners Hesper and Luther Little. During the early 1930s the early morning train from Albion to Wiscasset and the afternoon train back to Albion carried the last 2-foot gauge railway post office (RPO) in the United States. A derailment of the morning train in Whitefield on June 15, 1933, terminated railroad operations before the schooners could be loaded with lumber for shipment to larger coastal cities.[8] The two schooners were abandoned in Wiscasset shortly after Winter's premature demise in 1936, and they eventually became tourist attractions. Over the next 62 years, the weathered vessels became widely photographed as they were visible from a bridge along U.S. 1 that runs by the town. Wiscasset officials finally removed the rotted remains in 1998, after a violent storm took out the final masts.

Castle Tucker, built 1807

Castle Tucker, built 1807 Main Street in 1900

Main Street in 1900 Wiscasset Jail and Museum c. 1912

Wiscasset Jail and Museum c. 1912 Old Custom House and Post Office Built 1870

Old Custom House and Post Office Built 1870

Media

Wiscasset in literature

- Author Lea Wait has written an ongoing series of children's novels that are set in Wiscasset, including: Stopping to Home, set in 1806 (Named a Smithsonian Magazine Notable Children's Book); Seaward Born (1805, the setting of this book moved from Charleston, NC to Boston, MA to Wiscasset); Wintering Well (1820); Finest Kind (1838); and Uncertain Glory (1861).

- Wiscasset is one of many important Maine settings in The Moosepath Saga by Van Reid, an ongoing series of historical novels taking place in the late 1890s and including Cordelia Underwood, or the Marvelous Beginnings of the Moosepath League, which was named a New York Times Notable Book of the Year. In these tales of adventure and humor, events by turns perilous and comic occur in Wiscasset, including the hunt for an escaped circus bear and a pursuit and gun battle on the Sheepscott River off the shores of the town. Certain historic homes and landmarks, including the Old Jail, form part of the settings; and at least two characters – County Sheriff Charles Piper and Jailer Seth Patterson - are based on real people.

The books in the series in which Wiscasset plays an important part are Cordelia Underwood, or the Marvelous Beginnings of the Moosepath League; Mollie Peer, or the Underground Adventure of the Moosepath League; and Daniel Plainway, or the Holiday Haunting of the Moosepath League.

The climax of Reid's novel Peter Loon takes place in Wiscasset in 1801, using as its centerpiece of action an historic fomenting rebellion among back-country settlers and an actual escape that was successfully executed from the town's original jail.

In interviews, Reid has said that his having lived upriver in Sheepscott Village when young as well as tales of his father's childhood in 1930s Wiscasset has caused Wiscasset to “loom large” in his imagination.

Industry

From 1972 until 1996, Wiscasset was home to Maine Yankee, a pressurized water reactor on Bailey Point, and the only nuclear power plant in the state. The Maine Yankee nuclear power plant was decommissioned in 1996 and is inoperative. Since the closing of Maine Yankee, Wiscasset faced a severe loss in jobs, residents, and public school enrollment. In a high school graduation speech delivered by Bradley Whitaker, he stated, "The loss of those jobs changed our community, the surrounding towns and our school system. We've all had friends move away, our parents have had their taxes rise dramatically, enrollment has plummeted, we've watched teachers and administrators leave, programs and sports eliminated."[9][10]

The town attempted to replace Maine Yankee with a gasification plant in 2007, but the plan subsequently failed due to a town vote.[11]

Wiscasset was also home of the Mason Station, a coal and steam-powered plant along the Sheepscot River south of town that first went online in 1941. The plant went offline in 1991.[12] The property is currently proposed for redevelopment as a mixed-use office, light-industrial, residential and retail complex.[13]

In 2008, the Chewonki Foundation announced plans for a tidal power plant along the Sheepscot River.[14] A permit was issued by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) in 2009.[15] The project has not yet gone forward.

Rynel Inc., founded in 1973, developed and built processing equipment and hydrophilic polyurethane prepolymer products. The company was purchased by Mölnlycke Health Care company in 2010. In Jan 2014, the company announced its expansion plans for its Wiscasset, Maine manufacturing facility.[16]

National news

On May 1, 1991, a small fire erupted at the Maine Yankee Nuclear Power plant. The fire emitted a substantial amount of smoke which made it seem worse than it was. A video by photographer Keith Brooks was obtained by local media and was presented on NBC Nightly News. While the fire was not a significant threat, many locals believed it was a major concern for the environment, which caused several referendums to have the nuclear plant closed.

In 2009, the town lost a legal battle to reclaim an original copy of the Declaration of Independence[17] that was accidentally sold by the estate of the daughter of a former town official, Sol Holbrook. A Virginia court ruled the true owner was Richard L. Adams, Jr., who paid $475,000 for the document in 2002. The State of Maine paid nearly $40,000 in legal fees.[17]

Red's Eats, a small takeout restaurant located by the Donald E. Davey Bridge on Route 1, has been featured in more than 20 magazines and newspapers, including USA Today and National Geographic and several major television network newscasts, including Sunday Morning on CBS and a report by Bill Geist. The restaurant has been reported to be "the biggest traffic jam in Maine."[18]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 27.66 square miles (71.64 km2), of which, 24.63 square miles (63.79 km2) of it is land and 3.03 square miles (7.85 km2) is water.[1] Wiscasset is drained by the Sheepscot River.

Climate

This climatic region is typified by large seasonal temperature differences, with warm to hot (and often humid) summers and cold (sometimes severely cold) winters. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Wiscasset has a humid continental climate, abbreviated "Dfb" on climate maps.[19]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1810 | 2,083 | — | |

| 1820 | 2,138 | 2.6% | |

| 1830 | 2,255 | 5.5% | |

| 1840 | 2,314 | 2.6% | |

| 1850 | 2,332 | 0.8% | |

| 1860 | 2,318 | −0.6% | |

| 1870 | 1,977 | −14.7% | |

| 1880 | 1,847 | −6.6% | |

| 1890 | 1,733 | −6.2% | |

| 1900 | 1,273 | −26.5% | |

| 1910 | 1,287 | 1.1% | |

| 1920 | 1,192 | −7.4% | |

| 1930 | 1,186 | −0.5% | |

| 1940 | 1,231 | 3.8% | |

| 1950 | 1,584 | 28.7% | |

| 1960 | 1,800 | 13.6% | |

| 1970 | 2,244 | 24.7% | |

| 1980 | 2,832 | 26.2% | |

| 1990 | 3,339 | 17.9% | |

| 2000 | 3,603 | 7.9% | |

| 2010 | 3,732 | 3.6% | |

| Est. 2014 | 3,672 | [20] | −1.6% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[21] | |||

2010 census

As of the census[2] of 2010, there were 3,732 people, 1,520 households, and 993 families living in the town. The population density was 151.5 inhabitants per square mile (58.5/km2). There were 1,782 housing units at an average density of 72.4 per square mile (28.0/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 96.8% White, 0.5% African American, 0.4% Native American, 0.9% Asian, 0.1% from other races, and 1.4% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.0% of the population.

There were 1,520 households of which 27.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 49.1% were married couples living together, 10.9% had a female householder with no husband present, 5.3% had a male householder with no wife present, and 34.7% were non-families. 28.1% of all households were made up of individuals and 11.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.32 and the average family size was 2.79.

The median age in the town was 43.5 years. 19.7% of residents were under the age of 18; 8.8% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 24.1% were from 25 to 44; 31.1% were from 45 to 64; and 16.4% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the town was 50.6% male and 49.4% female.

2000 census

Per the census[22] of 2000, there were 3,603 people, 1,472 households, and 972 families living in the town. The population density was 146.5 inhabitants per square mile (56.6/km2). There were 1,612 housing units at an average density of 65.6 per square mile (25.3/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 98.00% White, 0.31% Black or African American, 0.17% Native American, 0.50% Asian, 0.31% from other races, and 0.72% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.67% of the population.

The median income for a household in the town was $37,378, and the median income for a family was $46,799. Males had a median income of $31,365 versus $21,831 for females. The per capita income for the town was $18,233. About 6.9% of families and 12.5% of the population were below the poverty line, including 16.2% of those under age 18 and 14.9% of those age 65 or over.

Sites of interest

Notable people

- Hugh J. Anderson, US congressman, 20th governor of Maine

- George E. Bailey, murder victim

- Jeremiah Bailey, US congressman

- Thomas Bowman, US congressman

- Franklin Clark, US congressman

- Juliana Hatfield, musician

- Marjoie Kilkelly, state legislator

References

- "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 16, 2012.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 16, 2012.

- "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- Coolidge, Austin J.; John B. Mansfield (1859). A History and Description of New England. Boston, Massachusetts: A.J. Coolidge. pp. 364–367.

coolidge mansfield history description new england 1859.

- Varney, George J. (1886), Gazetteer of the state of Maine. Wiscasset, Boston: Russell

- Peters, Bradley L. (1976). Maine Central Railroad Company. Maine Central Railroad.

- Jones, Robert C. & Register, David L. (1987). Two Feet to Tidewater The Wiscasset, Waterville & Farmington Railway. Pruett Publishing Company.

- http://www.timesrecord.com/articles/2010/06/11/news/doc4c12688cd2afa439237004.txt

- Ethan Whitaker (August 22, 2010). "Wiscasset High School - Senior Essay". Retrieved April 18, 2018 – via YouTube.

- http://www.democraticunderground.com/discuss/duboard.php?az=view_all&address=115x120219

- "History of CENTRAL MAINE POWER – FundingUniverse". www.fundinguniverse.com. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- "Possible Mason Station abatement". boothbayregister.com. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- http://www.coastaljournal.com/website/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=871&Itemid=1

- Stothart Connor, Betta (June 9, 2009). "Tidal Power Gets Initial Green Light in Town of Wiscasset". Retrieved April 11, 2014.

- "Mölnlycke Health Care expands Wiscasset manufacturing site". January 15, 2014. Retrieved April 11, 2014.

- Goodnough, Abby (December 11, 2007). "A Tug of War Over a Declaration of Independence". The New York Times.

- "red's eats - Yahoo Search Results". search.yahoo.com. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- "Wiscasset, Maine Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2014". Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

Further reading

- Jones, Robert C. & Register, David L. (1987). Two Feet to Tidewater The Wiscasset, Waterville & Farmington Railway. Pruett Publishing Company.

- Moody, Linwood W. (1959). The Maine Two-Footers. Howell-North.

- Barney, Peter S. (1986). The Wiscasset, Waterville and Farmington Railway: A Technical and Pictorial Review. A&M Publishing.

- Wiggin, Ruth Crosby (1971). Big Dreams and Little Wheels. Ruth Crosby Wiggin.

- Wiggin, Ruth Crosby (1964). Albion on the Narrow Gauge. Ruth Crosby Wiggin.

- Thurlow, Clinton F. (1964). The Weeks Mills "Y" of the Two-Footer. Clinton F. Thurlow.

- Thurlow, Clinton F. (1964). The WW&F Two-Footer Hail and Farewell. Clinton F. Thurlow.

- Thurlow, Clinton F. (1965). Over the Rails by Steam (A Railroad Scrapbook). Clinton F. Thurlow.

- Railroad Commissioners' Report. State of Maine. 1895, 1896, 1897, 1898, 1899, 1900, 1901, 1902, 1903, 1904, 1905, 1906, 1907, 1908, 1909, 1910, 1911, 1912, 1913 and 1914. Check date values in:

|year=(help) - Wright, Virginia. "What About Wiscasset?". Down East: The Magazine of Maine (August 2010).

- Cronk, Debbie Gagnon & Virginia Wright (2010). Red's Eats: World's Best Lobster Shack. Down East Books.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1879 American Cyclopædia article Wiscasset. |