William Lane

William Lane (6 September 1861 – 26 August 1917) was an Australian journalist, author, advocate of Australian labour politics and a utopian socialist ideologue.[1]

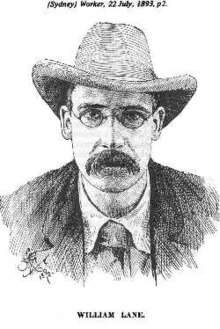

William Lane | |

|---|---|

A portrait of Lane, dated 1893 | |

| Born | 6 September 1861 Bristol, England |

| Died | 26 August 1917 (aged 55) Auckland, New Zealand |

| Nationality | Australian |

| Occupation | Journalist, author, co-founder of New Australia |

| Known for | Journalism, political advocacy |

| Part of a series on |

| Socialism in Australia |

|---|

|

|

History |

|

Literature Newspapers/Journals/Magazines

Active Historical |

|

Lane was born in Bristol, England into an impoverished family. After showing great skill in his education, he worked his way into Canada as first a linotype operator, then as a reporter for the Detroit Free Press where he would later meet his future wife Ann Lane, née Macquire. After settling in Australia with his wife and child, as well as his brother John, he became active in the Australian labour movement, founding the Australian Labour Federation and becoming a prolific journalist for the movement. He authored works covering topics such as labour rights and white nationalism.

After becoming disillusioned with the state of Australian politics following an ideological split in the labour movement, he and a group of utopian acolytes (among them influential writer and poet Mary Gilmore) moved to Paraguay in 1892 to found New Australia, with the intention of building a new society on the foundations of his utopian ideals. Following disagreement with the colony regarding the legality of miscegenation and alcohol consumption, he left to found the nearby colony Cosme in May 1894, and later abandoned the project altogether in 1899.

Upon resetting in New Zealand he continued his journalistic endeavours until his death in August 1917. After his death he was both celebrated as a champion of utopian socialism, and condemned as the arrogant leader of a failed new society. Due to his radical politics and his extensive journalistic career, he remains a controversial figure in Australian history.

Early life

Lane was born in Bristol, England on 6 September 1861, as the eldest son of James Lane, an Irish Protestant landscape gardener, and his English wife Caroline, née Hall.[1] Lane was born with a debilitating clubfoot, a condition that would be partially corrected in Montreal later in life, leaving him with a limp. Lane's father James was a drunkard who when Lane was born was earning a miserable wage, but later he improved his circumstances and became an employer.

The young Lane was educated at Bristol Grammar School and demonstrated himself as a gifted student, but he was sent early to work as an office boy. Lane's mother died when he was 14 years of age, and at age 16 he migrated to Canada where he worked odd jobs such as a linotype operator. During this time he began engrossed in the writings of economist Henry George and socialist Edward Bellamy. In 1881 by the age of 24 he became a reporter for the Detroit Free Press, where he would meet his future wife Ann Macquire whom he would marry on 22 July 1883.

Radical journalism in Australia

In 1885 William and Ann Lane, along with brother John, as well as their first child migrated to Brisbane, Australia, where Lane immediately got work as a feature writer for the weekly newspaper Queensland Figaro, then as a columnist for the newspapers Brisbane Courier and the Evening Telegraph, using a number of pseudonyms (Lucinda Sharpe, which some consider to be the work of Lane's spouse; William Wilcher; and Sketcher).

Lane's childhood experiences as the son of a drunkard fashioned him into a lifelong abstainer from alcohol. In 1886 he created an Australia-wide sensation by spending a night in the Brisbane lock-up disguised as a drunk, and subsequently reporting the conditions of the cells as "Henry Harris". Lane's father was a drunk who impoverished the family.[1]

With the growth of the Australian labour movement, Lane's columns under the Sketcher pseudonym, especially his "Labour Notes" in the Evening Telegraph, began to increasingly promote labourist philosophy. Lane himself began to attend meetings supporting all manner of popular causes, speaking against repressive laws and practices and Chinese immigrants, all while utilising a charismatic American intonation he had attained during his time in the States.

After becoming the de facto editor of the Sydney Morning Herald, Lane left the newspaper during November 1887 to found the weekly The Boomerang, a newspaper described as "a live newspaper, racy, of the soil", in which pro-worker themes and lurid racism were brought to a fever-pitch by both Sketcher and Lucinda Sharpe. He became a powerful supporter of Emma Miller and women's suffrage. A strong proponent of Henry George's Single Tax Movement, Lane became increasingly committed to a radically alternative society, and ended his relationship with the Boomerang due to its private ownership.

In May 1890 he began the trade union funded Brisbane weekly The Worker, the rhetoric of which became increasingly threatening towards the employers, the government, and the British Empire itself. The defeat of the 1891 Australian shearers' strike convinced Lane that there would be no real social change without a completely new society, and The Worker became increasingly devoted to his New Australia utopian idea which would later be made a reality.

White or Yellow?

Although his efforts were primarily directed towards the non-fictional, Lane was an avid author whose works deeply reflected his political philosophy, as short as his bibliography is. The Workingman's Paradise, an allegorical novel written in sympathy with those involved in the 1891 shearers' strike, was published under his pseudonym John Miller in early 1892. In the novel Lane articulated the belief that anarchism is the noblest social philosophy of all. Through the novel's philosopher and main protagonist he relates his belief that society may have to experience a period of state socialism to achieve the ideal of anarcho-communism. Mary Gilmore, later a celebrated Australian writer, said in one of her letters that "the whole book is true and of historical value as Lane transcribed our conversations as well as those of others".

Most prominent in his bibliography is his novella White or Yellow?: A Story of the Race War of A.D. 1908 (1887). In this work, Lane proposed a horde of Chinese people would legally arrive to Australia, who would then overrun White society and monopolise the industries important to exploiting the natural resources of the "empty north" of the continent.[3] As Australian invasion literature, White or Yellow? reflects Lane's nationalist racialism and left-wing politics within a future history of Australia under attack by the Yellow Peril.

Lane wrote that in the near future, British capitalists would manipulate the legal system and successfully arrange the mass immigration of Chinese workers to Australia, regardless of its socioeconomic consequences to Australian common folk and their society. The economic, cultural, and sexual conflicts that resulted from the capitalists' manipulation of the Australian economy would then provoke a race war throughout the continent, fought between the White settlers and Chinese workers.

The racialist representations of Yellow Peril ideology in the narrative of White or Yellow? work to justify forcible expulsion and murder of Chinese workers as an acceptable response to the loss of physical and economic control of Australia.[4]:26–27 Historically the leaders of the Australian labour and trade unions greatly opposed the importation of Chinese workers, whom they portrayed as an economic threat to Australia due to their eagerness to work for low wages, as well as them presenting a libertine and race-diluting threat to Christian civilisation. Lane's work was intended to act as an apolitical call to racial unity among white Australians.[4]:24

New Australia Colony

Contriving a division among Australian labour activists between the permanently disaffected and those who later formed the Australian Labor Party, Lane refused the Queensland Government's offer of a grant of land on which to create a utopian settlement, and began an Australia-wide campaign for the creation of a new society elsewhere on the globe, peopled by rugged and sober Australian bushmen and their proud wives.

Eventually Paraguay was decided upon, and Lane and his family and hundreds of acolytes (238 total) from New South Wales, Queensland and South Australia departed Mort Bay in Sydney in the ship Royal Tar on 1 July 1893.[5][6]

New Australia soon had its crisis, brought on by the issues of interracial relationships (Lane singled out the Guarani as racially taboo) and alcohol. Lane's dictatorial manner soon alienated many in the community, and by the time the second boatload of utopians arrived from Adelaide in 1894, Lane had left with a core of devotees to form a new colony nearby named Cosme.[7][8]

Eventually Lane became disillusioned with the process, and returned to Australia in 1899.

Later life

Lane then went with his family to New Zealand. After initial melancholia, he soon refound his old verve as a pseudonymous feature writer from 1900 for the newspaper New Zealand Herald ("Tohunga"), only this time as ultra-conservative and pro-Empire. He had retained the strong racial antipathy toward East Asians he expressed in his literature, and during World War I he developed extreme anti-German sentiments. He died on 26 August 1917 in Auckland, New Zealand, having been editor of the Herald from 1913 to 1917, much admired, having lost one son Charles at a cricket match in Cosme in Paraguay, and another Donald on the first day of the ANZAC landings (25 April 1915) on the beaches of Gallipoli.

Bibliography

- White or Yellow?: A Story of the Race War of A.D. 1908 (1887)

- The Workingman's Paradise (1892)

References

- Gavin Souter (1983). "Lane, William (1861–1917)". Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 9. MUP. pp. 658–659. Archived from the original on 21 March 2007. Retrieved 27 April 2007.

- See Museum Victoria description Archived 5 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Affeldt, Stefanie (12 July 2011). "'White Sugar' against 'Yellow Peril' Consuming for National Identify and Racial Purity" (PDF). University of Oxford. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 October 2018. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- Auerbach, Sascha. Race, Law, and "The Chinese Puzzle" in Imperial Britain, London: Macmillan, 2009

- "Places You Can No Longer Go: New Australia – Atlas Obscura". Atlas Obscura. Archived from the original on 27 March 2016. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- National Treasures from Australia's Great Libraries. National Library Australia. 1 January 2005. ISBN 9780642276209.

- McLeod, Allan (27 May 1927). "AN ACCOUNT OF WILLIAM LANE'S COSME SETTLEMENT IN PARAGUAY". Windsor And Richmond Gazette. 39 (2065). New South Wales, Australia. p. 2. Retrieved 19 October 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- "1893 The New Australia Colony Collection: Australia's migration history timeline". www.migrationheritage.nsw.gov.au. NSW Migration Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 12 March 2016. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

Further reading

- Gavin Souter's account of Lane and New Australia in his A Peculiar People

- Peter Bruce's thesis (Univ Sydney) The Journalistic Career of William Lane.

- Larry Petrie (1859–1901) – Australian Revolutionist? by Bob James

- Whitehead, Anne (1997) Paradise Mislaid – in Search of the Australian Tribe of Paraguay University of Queensland Press, St. Lucia

- Serle, Percival (1949). "Lane, William". Dictionary of Australian Biography. Sydney: Angus and Robertson. Retrieved 7 September 2009.