William Blakeney, 1st Baron Blakeney

Lieutenant General Sir William Blakeney, 1st Baron Blakeney, KB, 7 September 1672 to 20 September 1761, was an Irish-born officer, who served in the British army from 1695 until 1756. He was Member of Parliament for Kilmallock from 1725 to 1757, although rarely attended.

Sir William Blakeney | |

|---|---|

Lieutenant-General Sir William Blakeney | |

| Member of Parliament for Kilmallock, Irish Parliament | |

| In office 1725–1757 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 7 September 1672 Mount Blakeney, County Limerick, Ireland |

| Died | 20 September 1761 (aged 89) Mount Blakeney, County Limerick, Ireland |

| Resting place | Westminster Abbey |

| Citizenship | British |

| Nationality | Irish |

| Relations | Robert Blakeney (1679-1733); |

| Parents | William (1640–1718); Elizabeth (1652–1710) |

| Occupation | Soldier and landowner |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1695-1756 |

| Rank | Lieutenant General |

| Unit | Colonel, 27th Foot, later Inniskilling Regiment |

| Commands | Stirling Castle Plymouth Menorca |

| Battles/wars | Nine Years War 1695 Siege of Namur War of the Spanish Succession Schellenberg Blenheim Malplaquet War of Jenkins' Ear Cartagena de Indias Cuba Jacobite rising of 1745 Stirling Castle Seven Years' War Fort St Philip |

A tough, reliable and courageous soldier, Blakeney was also known for his innovative approach to weapons drill and training. One of the few officers to bolster their reputation during the Jacobite rising of 1745, he was rewarded by being appointed Lieutenant-Governor of the British-held island of Menorca in 1748.

When the Seven Years' War began in April 1756, the French occupied most of the island, although Blakeney and the garrison of Fort St. Philip held out for 70 days. Admiral John Byng was later court-martialled and shot for failing to relieve him, but Blakeney was made a baronet in recognition of his resolute defence.

Then in his 80s, this ended his military career, and he retired to County Limerick, Ireland; he died there in September 1761, and was later buried in Westminster Abbey. He never married, and the title became extinct on his death.

Life

William Blakeney was born on 7 September 1672, eldest child of William (1640–1718), and Elizabeth Blakeney (1652–1710). His siblings included Robert (died 1763), Charles (1674–1741), John (1696–1720), Mary (born c. 1678), Catherine (born 1680) and Elizabeth (died 1740).[1]

William Blakeney owned estates at Castleblakeney, in County Galway, and Mount Blakeney, in County Limerick. The family supplied the MP for Athenry and High Sheriff of County Galway for over a century. Blakeney inherited his father's property, but reputedly lived on his military pay and allowed his brothers use of the family estate. He never married, and the property passed to Major Robert Blakeney, his younger brother.[1]

Career

1695 to 1739

In March 1689, the exiled James II landed in Ireland to regain his throne, leading to the 1689 to 1691 Williamite War. Blakeney remained at Mount Blakeney to defend his estates against raids by Irish irregulars or Rapparees, while the rest of his family relocated to Castleblakeney.[1]

His uncle George Blakeney was serving in Flanders where Blakeney joined him, initially as a volunteer. He was wounded at the Siege of Namur on 31 August 1695 during the attack on the Terra Nova earthwork; this action allegedly inspired the song 'The British Grenadiers'.[2]

In September 1695, he was commissioned as an ensign in The Royal Regiment of Foot, then placed on half-pay after the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick.[3] When the War of the Spanish Succession began in 1701, he was reactivated and fought at the battles of Schellenberg, Blenheim and Ramillies. He was promoted captain in April 1707.[4]

In March 1708, he was commissioned as a lieutenant in the Foot Guards, although only 16 of its nominal 24 companies were actually formed, and Blakeney remained with his original unit.[5] Under the practice known as double-ranking, Guards officers held a second, higher army rank; for example, a Guards lieutenant ranked as an army major.[6] Guard units were rarely disbanded, and their officers were given precedence when deciding promotions, making it a cheap way to reward competent, but poor officers. John Huske (1692–1761), a colleague during the 1745 Rebellion, was commissioned in the Guards for similar reasons.[7]

Blakeney's regiment escaped disbandment after the 1713 Peace of Utrecht; when his uncle retired from the 31st Foot in 1718, he assigned his commission as lieutenant colonel to his nephew.[8] Blakeney retained this position for the next 20 years; some biographers suggest he was deliberately held back, but promotion in this period was slow for all officers.[9] He became colonel of the 27th Foot in 1737, with the support of the Duke of Richmond.[1]

1740 to 1748

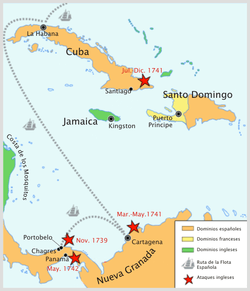

When trade disputes with Spain led to the outbreak of the War of Jenkins' Ear in 1739, Blakeney was appointed brigadier general in the expeditionary force sent to reinforce Admiral Vernon. His reputation for training was a factor in his selection, since the force included 3,000 newly recruited American colonial militia.[1]

He took part in the disastrous attack of March 1741 on Cartagena de Indias and the short-lived occupation of Cuba. The West Indies was a notoriously unhealthy posting, and simply surviving was an achievement. Between 1740 and 1742, British navy and army deaths from disease and combat were estimated as over 20,000, with death rates of 80–90% among land forces.[10]

With little to show for the investment of men and money, the survivors returned to Britain in October 1742.[11] Blakeney was appointed lieutenant governor of Stirling Castle, an immensely strong position controlling access between the Scottish Highlands and the Lowlands.[12] In September 1745, the Jacobite army passed the castle en route to Edinburgh, but lacked the equipment needed to take it.[13]

The Jacobites made a more serious attempt in the Siege of Stirling Castle in January 1746, but progress was slow. Despite victory at Falkirk Muir on 1 February, the Jacobites lifted the siege and withdrew to Inverness when Prince William, Duke of Cumberland began advancing north from Edinburgh.[14] The Rising ended at the Battle of Culloden in April 1746. Blakeney was promoted lieutenant general and given military command of the Highlands.[15]

1748 to 1761

In 1748, he was appointed lieutenant governor of Menorca; captured by the British in 1708, the island was considered vital for control of the Western Mediterranean. However, it was also vulnerable; the Spanish deeply resented British occupation, while it was only two days sail from Cádiz, and one from the French naval base at Toulon.[16]

Since the nominal governor, Baron Tyrawley, never visited Menorca, Blakeney was its effective ruler. He attempted to reduce local opposition by encouraging his troops to marry local women, and by controlling Catholic schools and institutions, but neither of these measures was successful.[17] Tyrawley's absence was symptomatic of general neglect; in 1757, a Parliamentary committee noted the poor state of its defences, with crumbling walls and rotten gun platforms. In addition to Tyrawley, over 35 senior officers were absent from their posts, including the governor of Fort St Philip, and the colonels of all four regiments in its garrison.[18]

When the Seven Years' War began in April 1756, the French quickly occupied the island and began the Siege of Fort St Philip, which was commanded by Blakeney.[1] An attempt by Admiral John Byng to lift the siege was repulsed in May, and Blakeney surrendered on 29 June. The garrison was given free passage to Gibraltar, whose governor was Thomas Fowke, court-martialled but acquitted in 1746 for the defeat at Prestonpans.[19]

In the inquiry that followed, Fowke was dismissed for failing to provide reinforcements from the Gibraltar garrison, while Byng was executed in March 1757.[20] The heavy drinking that left Blakeney with "a paralytick disorder" and "nervous tremors", was portrayed as the virtues of a simple soldier, but many considered his surrender premature.[21] Although rewarded by being appointed to the Order of the Bath and made 'Baron Blakeney' in the Irish peerage, delirium tremens left him barely able to write his name, and this ended his military career.[22]

Legacy

Weapons drill and infantry training was a common topic among professional officers; Blakeney suggested using puppets to demonstrate drill positions to recruits. After Culloden, he was invited to demonstrate 'firings and evolutions of my own design' but in 1748, a new standard infantry drill manual was issued and Blakeney dropped his suggestions.[23]

In 1759, the Friendly Brothers of Saint Patrick paid for a statue of Blakeney by sculptor John Van Nost to be erected in Dublin.[24] Removed in 1763, the space was later filled by Nelson's Pillar, itself replaced in 1968 by the Spire of Dublin.[25]

He died on 20 September 1761 in Ireland and later buried in the nave of Westminster Abbey; the gravestone still exists, but the inscription is now very faint.[26]

References

- Harding 2008.

- Lenihan 2011, p. 298.

- Dalton 1904, p. 253.

- Dalton 1904, p. 94.

- Dalton 1904, p. 318.

- Springman 2008, p. 11.

- Dalton 1904, pp. 319-320.

- "Lt.-Col. George Blakeney 276301". The Peerage. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- Sanghvi 2017, pp. 1–2.

- Browning 1994, p. 382.

- Woodfine 1987, p. 71.

- Henshaw 2014, p. 121.

- Duffy 2003, p. 191.

- Stair-Kerr 1928, p. 131.

- Royle 2016, p. 113.

- Donaldson 1994, p. 383.

- Royle 2016, pp. 342-343.

- Debrett 1792, p. 295.

- Blaikie 1916, p. 434.

- Regan 2000, p. 35.

- McGuffie 1950, p. 182.

- McGuffie 1951, p. 115.

- Houlding 1978, p. 252.

- Fraser 1956, pp. 34–40.

- Fallon, Donal (15 August 2013). "Before the Admiral: The vanishing statue of William Blakeney". Come Here to Me; Dublin Life & Culture. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- "William Blakeney". Westminster Abbey. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

Sources

- Blaikie, Walter Biggar, ed. (1916). Publications of the Scottish History Society (Volume Series 2, Volume 2 (March, 1916) 1737-1746). Scottish History Society.

- Browning, Reed (1994). The War of the Austrian Succession. Sutton Publishing. ISBN 978-0750905787.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dalton, Charles (1904). English army lists and commission registers, 1661-1714 Volume VI. Eyre & Spottiswood.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Debrett (1792). History, Debates & Proceedings of Parliament 1743-1774; Volume III. Debrett.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Donaldson, David Whalom (1994). Britain and Menorca in the 18th century; Volume 3. Open University.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Duffy, Christopher (2003). The '45: Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Untold Story of the Jacobite Rising. Orion. ISBN 978-0304355259.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fraser, AM (August 1956). "The Friendly Brothers of St. Patrick". Dublin Historical Record. 14 (2).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Henshaw, Victoria (2014). Scotland and the British Army, 1700-1750: Defending the Union. Bloomsbury 3PL. ISBN 978-1472507303.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Houlding, John Alan (1978). The Training of the British Army 1715-1795. Kings College London PHD.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lenihan, Padraig (2011). "Namur Citadel, 1695: A Case Study in Allied Siege Tactics" (PDF). War in History. 18 (3).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McGuffie, TH (1950). "The Defence of Minorca 1756". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 28 (115).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McGuffie, TH (1951). "Some fresh light on the siege of Minorca, 1756". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 29 (119).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Regan, Geoffrey (2000). Brassey's Book of Naval Blunders. Brassey's. ISBN 978-1574882537.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Royle, Trevor (2016). Culloden; Scotland's Last Battle and the Forging of the British Empire. Little, Brown. ISBN 978-1408704011.

- Sanghvi, Neil (2017). Gentlemen of Leisure or Vital Professionals? The Officer Establishment of the British Army, 1689- 1739. PHD Thesis; St Hilda's College Oxford.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Springman, Michael (2008). The Guards Brigade in the Crimea (2014 ed.). Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1844156788.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stair-Kerr, Eric (1928). Stirling Castle: Its Place in Scottish History (Classic Reprint). Forgotten Books. ISBN 978-1331341758.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harding, Richard (2008). "Blakeney, William, Baron Blakeney". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/2591.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Woodfine, PL (1987). "The War of Jenkins Ear; the Vernon-Wentworth debate". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 65 (262).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- "William Blakeney". Westminster Abbey.

- Fallon, Donal (15 August 2013). "Before the Admiral: The vanishing statue of William Blakeney". Come Here to Me; Dublin Life & Culture.

- "Lt.-Col. George Blakeney 276301". The Peerage.

- "Mount Blakeney". Landed Estates Database.

| Parliament of Ireland | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Kilner Brasier |

Member of Parliament for Kilmallock 1725–1757 |

Succeeded by Silver Oliver |

| Military offices | ||

| Preceded by Archibald Hamilton |

Colonel, 27th Foot, later Inniskilling Regiment 1737–1761 |

Succeeded by Hugh Warburton |

| Peerage of Ireland | ||

| New creation | Baron Blakeney 1756–1761 |

Extinct |