Whitman massacre

The Whitman massacre (also known as the Walla Walla massacre and the Whitman Incident) was the murder of Washington missionaries Marcus Whitman and his wife Narcissa, along with eleven others, on November 30, 1847. They were killed by members of the Cayuse tribe who accused him of having poisoned 200 Cayuse in his medical care.[1] The incident began the Cayuse War. It took place in southeastern Washington state near the town of Walla Walla, Washington and was one of the most notorious episodes in the U.S. settlement of the Pacific Northwest. Whitman had helped lead the first wagon train to cross Oregon's Blue Mountains and reach the Columbia River via the Oregon Trail, and this incident was the climax of several years of complex interaction between him and the local Indians.[2] The story of the massacre shocked the United States Congress into action concerning the future territorial status of the Oregon Country, and the Oregon Territory was established on August 14, 1848.

| Whitman Massacre | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Cayuse War | |

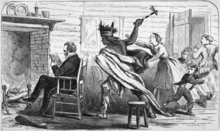

Dramatic depiction of the incident, from Eleven years in the Rocky Mountains and a life on the frontier by Frances Fuller Victor. | |

| Location | Waiilatpu mission, near Walla Walla, Washington |

| Coordinates | 46°02′32″N 118°27′51″W |

| Date | November 29, 1847 |

| Deaths | 13 |

| Victims | White American residents of the Waiilatpu mission |

| Perpetrators | Tiloukaikt, Tomahas, Kiamsumpkin, Iaiachalakis, and Klokomas |

| Motive | The belief that Marcus Whitman was deliberately poisoning American Indians infected with measles |

The killings are usually ascribed in part to a clash of cultures and in part to the inability of Whitman, a physician, to halt the spread of measles among the Indians. The Cayuse held Whitman responsible for subsequent deaths. The incident remains controversial to this day; the Whitmans are regarded by some as pioneer heroes, while others see them as white settlers who had attempted to impose their religion on the Indians and otherwise intrude, even allegedly poisoning them.[3]

Background

Sahaptin nations came into direct contact with whites several decades before the arrival of the members of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM). These relations set expectations among the Cayuse for how exchanges and dialogue with whites would operate. Primarily the early Euro-Americans engaged in the North American fur trade and the Maritime fur trade. Marine captains regularly gave small gifts to indigenous merchants as a means to encourage commercial transactions. Later land-based trading posts, operated by the Pacific Fur Company, the North West Company and the Hudson's Bay Company, regularized economic and cultural exchanges, including gift giving. Interactions were not always peaceful. Native Americans suspected that the whites had power over the new diseases that they suffered. Reports from the period note that members of the Umpqua, Makah, and Chinookan nations faced threats of destruction through white-carried illnesses, as the natives had no immunity to these new infectious diseases.[4] After becoming the premier fur gathering operation in the region, the HBC continued to develop ties on the Columbian Plateau.

Historian Cameron Addis recounted that after 1840, much of the Columbian Plateau was no longer important in the fur trade and that:

... most of its people were not dependent on agriculture, but traders had spread Christianity for thirty years. When Catholic and Protestant missionaries arrived they met Indians already content with their blend of Christianity and native religions, skeptical toward farming, and wary of the whites' apparent power to inflict diseases. Local Indians expected trade and gifts (especially tobacco) as part of any interaction with whites, religious or medical.[5]

Establishment of the mission

Samuel Parker and Marcus Whitman journeyed overland in 1835 from the Rocky Mountains into portions of the modern states of Idaho, Oregon, and Washington to locate potential mission locations. Parker hired a translator from Pierre-Chrysologue Pambrun, manager of the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) trading post Fort Nez Percés. He wanted help in consulting with the elite of the Liksiyu (Cayuse) and Niimíipu (Nez Perce) in order to identify particular places for missions and Christian proselytizing.

During specific negotiations over what became the Waiilatpu Mission, six miles from the site of the present-day city of Walla Walla, Washington, Parker told the assembled Cayuse men that:

I do not intend to take your lands for nothing. After the Doctor [Whitman] is come, [sic] there will come every year a big ship, loaded with goods to be divided among the Indians. Those goods will not be sold, but given to you. The missionaries will bring you plows and hoes, to teach you how to cultivate the land, and they will not sell, but give them to you."[6]

Early contact

Whitman returned the following year with his wife, mechanic William H. Gray, and the missionary couple Rev. Henry Spalding and Eliza Hart Spalding. The wives were the first known white American women to enter the Pacific Northwest overland. HBC Chief Factor Dr. John McLoughlin advised against the missionaries residing on the Columbia Plateau, but offered material support for their venture regardless. In particular, he allowed the women to reside at Fort Vancouver that winter as the men went to begin work on constructing the Waiilatpu Mission.[7]

Because the beaver population of the Columbian Plateau had declined, British fur trading activities were being curtailed. Despite this, the HBC practices during previous decades shaped the perceptions and expectations of the Cayuse in relation to the missionaries. Whitman was frustrated because the Cayuse always emphasized commercial exchanges. In particular, they requested that he purchase their stockpiles of beaver skins, at rates comparable to those at Fort Nez Percés.[7] The Mission supplies were, in general, not appealing enough to the Sahaptin to serve as compensation for their labor. Whitman lacked sizable stockpiles of gunpowder, tobacco, or clothing, so he had to assign most labor to Hawaiian Kanaka (who had settled after working as sailors) or whites.[8] To bolster food supplies for the first winter, Whitman purchased several horses from the Cayuse. Additionally, the initial plowing of the Waiilatpu farm was done primarily with draft animals loaned by a Cayuse noble and Fort Nez Percés.[7]

The missionary family suffered from a lack of privacy, as the Cayuse thought nothing of entering their quarters. Narcissa complained that the kitchen was "always filled with four or five or more Indians-men-especially at meal time ... " and said that once a room was established specifically for Indigenous that the missionaries would "not permit them to go into the other part of the house at all ... ". According to Narcissa, the Natives were "so filthy they make a great deal of cleaning wherever they go ... "[9] She wrote that "we have come to elevate them and not to suffer ourselves to sink down to their standard."[9]

In the beginning of 1842, when the Cayuse returned to the vicinity of Waiilatpu after winter, the Whitmans told the tribesmen to establish a house of worship for their use. The Cayuse noblemen disagreed, stating that the existing mission buildings were sufficient. The Whitmans tried to explain that "we could not have them worship there for they would make it so dirty and fill it so full of fleas that we could not live in it."[9] The Cayuse who visited the Whitman's found Narcissa's haughtiness and Marcus' refusal to hold sermons in the mission household to be rude.[5]

Land ownership dispute

The Cayuse allowed construction of the mission, in the belief that Parker's promises still held.[6] During the summer of 1837, a year after construction had started, the Whitmans were called upon to make due payment. The chief who owned the surrounding land was named Umtippe. Whitman balked at his demands and refused to fulfill the agreement, insisting that the land had been granted to him free of charge.[10]

Umtippe returned the following winter to again demand payment, along with medical attention for his sick wife. He informed Whitman that "Doctor, you have come here to give us bad medicines; you come to kill us, and you steal our lands. You had promised to pay me every year, and you have given me nothing. You had better go away; if my wife dies, you shall die also."[6] Cayuse men continued to complain to HBC traders of Whitman's refusal to pay for using their land and of his preferential treatment of incoming white colonists.[11]

In particular, the Cayuse leader impeded Gray's cutting of timber intended for various buildings at Waiilatpu. He demanded payment for the lumber and firewood gathered by the missionaries. These measures were intended to delay the use of the wood resources, as a settler in the Willamette Valley had suggested to the noble that he would establish a trading post in the vicinity.[10] During 1841, Tiloukaikt kept his horses within the Waiilatpu farm, earning Whitman's enmity as the horses destroyed the maize crop.

Whitman claimed that the farmland was specifically for the mission and not for roving horses. Tiloukaikt told the doctor " ... that this was his land, that he grew up here and that the horses were only eating up the growth of the soil; and demanded of me what I had ever paid him for the land."[10] Aghast at the demands, Whitman told Tiloukaikt that "I never would give him anything ... "[10] During the start of 1842, Narcissa reported that the Cayuse leaders "said we must pay them for their land we lived on."[9] A common complaint was that Whitman sold wheat to settlers, while giving none to the Cayuse landholders and demanding payment from them for using his grist mill.[11]

Conversion efforts

The Catholic Church dispatched two priests in 1838 from the Red River colony to minister to the spiritual needs of both the regional Indigenous and Catholic settlers. François Norbert Blanchet and Modeste Demers arrived at Fort Nez Percés on 18 November 1839.[12] This began a long-lasting competition between the ABCFM and the Catholic missionaries to convert the Sahaptin peoples to Christianity. While Blanchet and Demers were at the trading post for one day, they preached to an assembled group of Walla Wallas and Cayuse. Blanchet would later allege that Whitman had ordered local natives against attending their service.[12] Whitman contacted the agent McLoughlin to complain of the Catholic activity. McLoughlin responded saying he had no oversight of the priests, but would advise them to avoid the Waiilaptu area.[13]

The rival missionaries competed for the attention of Cayuse noble Tawatoy. He was present when the Catholic priests held their first Mass at Fort Nez Percés. Demers returned to the trading post for two weeks in the summer of 1839.[14] One of Tawatoy's sons was baptized at this time and Pierre-Chrysologue Pambrun was named as his godfather.[12] According to Whitman, the Catholic priest forbade Tawatoy from visiting him.[13] While Tawatoy did occasionally visit Whitman, he avoided the Protestant's religious services.[15] Also, the headman gave the Catholics a small house which Pambrun had built for him, for their use for religious services.[15]

After Demers left the area in 1840, Whitman preached to assembled Cayuse on several occasions, saying that they were in a "lost ruined and condemned state ... in order to remove the hope that worshipping will save them."[8] While he faced threats of violence for denying the power of worship,[16] Whitman continued to tell the Cayuse that their interpretation of Christianity was wrong.

Whitman had opposed closing the Waiilatpu Mission, as suggested by Asa Bowen Smith in 1840, because he thought it would allow "the Catholics to unite all the [Pacific] coast from California to the North ... "[16] Religious strife continued between the two Christian denominations. Cayuse and related natives "brought under papal influences" was, according to the ABCFM board, "manifest less confidence in the ceremonies of that delusive system."[17] Despite this claim, in 1845 the board admitted that no Cayuse had formally joined the churches maintained by ABCFM missionaries.[18]

Henry Spalding and other anti-Catholic ministers later claimed that the Whitman killings were instigated by Catholic priests. According to their accounts, the Catholics may have told the Cayuse that Whitman had caused disease among their people and incited them to attack. Spalding and other Protestant ministers suggested that the Catholics wanted to take over the Protestant mission, which Whitman had refused to sell to them. They accused Fr. Pierre-Jean De Smet of being a party to such provocations.

Agriculture

Whitman and his fellow missionaries urged the adjacent Plateau peoples to learn to adopt European-American style agriculture, and settle on subsistence farms. This topic was a common theme in their dispatches to the Secretary of ABCFM, Rev. David Greene.[7][15][19] Trying to persuade the Cayuse to abandon their seasonal migrations consumed much of Whitman's time. He believed that if they would cultivate their food supply through farming, they would remain in the vicinity of Waiilaptu. He told his superiors that if the Cayuse would abandon their habit of relocating during the winter, he could spend more time proselytizing among them. In particular, Whitman told Rev. Green that " ... although we bring the gospel as the first object we cannot gain an assurance unless they are attracted and retained by the plough and hoe ... "[20]

In 1838 Whitman wrote about his plans to begin altering the Cayuse diet and lifestyle. He asked to be supplied with a large stockpile of agricultural equipment, so that he could lend it to interested Cayuse. He also needed machinery to use in a grist mill to process any wheat produced. Whitman believed that a mill would be another incentive for the Cayuse nation to stay near Waiilaptu.[19] To allow him some freedom from secular tasks, Whitman began to ask that a farmer be hired to work at his station and advise the Cayuse.[8]

The Cayuse started to harvest various acreages of crops originally provided to them by Whitman. Despite this, they continued their traditional winter migrations. The ABCFM declared in 1842 that the Cayuse were still " ... addicted to a wandering life".[21] The board said that the natives were "not much inclined to change their mode of life ... "[21] During the winter of 1843-44, food supplies were short among the Cayuse. As the ABCFM recounted:

The novelty of working for themselves and supplying their own wants seem to have passed away; while the papal teachers and other opposers of the mission appear to have succeeded in making them believe that the missionaries ought to furnish them with food and clothing and supply all their wants.[17]

Rising tensions

An additional point of contention between Whitman and the Cayuse was the missionaries' use of poisons. John Young, an immigrant from the United States, reported two cases in particular that strained relations.[22] In 1840, he was warned by William Gray of the mission melon patch, the larger of them poisoned. This was from Cayuse taking the produce, to safeguard the patch Gray stated that he " ... put a little poison ... in order that the Indians who will eat them might be a little sick ... "[22] During the winter of 1846, Young was employed on the mission sawmill. Whitman gave him instructions to place poisoned meat in the area surrounding Waiilatpu to kill Northwestern wolves. Several Cayuse ate the deadly meat but survived. Tiloukaikt visited Waiilatpu after the people recovered, and said that if any of the sick Cayuse had died, he would have killed Young.[22] Whitman reportedly laughed when told of the conversation, saying he had warned the Cayuse several times of the tainted meat.[22]

Measles was an epidemic around Sutter's Fort in 1846, when a party of primarily Walla Wallas were there. They carried the contagion to Waiilatpu as they ended the second Walla Walla expedition, and it claimed lives among their party. Shortly after the expedition reached home, the disease appeared among the general population around Walla Walla and quickly spread among the tribes of the middle Columbia River.[23]

By the 1940s, historians no longer considered the measles epidemic as a main cause of the murders at Waiilaptu. Robert Heizer said that "This measles epidemic, as an important contributing factor to the Whitman massacre, has been minimized by historians searching for the cause of the outrage."[24]

The Cayuse involved in the incident had previously lived at the Waiilatpu mission. Among the many new arrivals at Waiilatpu in 1847 was Joe Lewis, a mixed-race Iroquois and white "halfbreed." Bitter from discriminatory treatment in the East, Lewis attempted to spread discontent among the local Cayuse, hoping to create a situation in which he could ransack the Whitman Mission. He told the Cayuse that Whitman, who was attempting to treat them during a measles epidemic, was not trying to save them but to poison them. The Columbia Plateau tribes believed that the doctor, or shaman, could be killed in retribution if patients died. [25] It is likely that the Cayuse held Whitman responsible for the numerous deaths and therefore felt justified to take his life. The Cayuse feared that he had treated them with strychnine,[26][27] or that someone from the Hudson's Bay Co. had injected strychnine into the medicine after Whitman had given it to the tribe.[5]

Outbreak of the violence

On November 29, Tiloukaikt, Tomahas, Kiamsumpkin, Iaiachalakis, Endoklamin, and Klokomas, enraged by Joe Lewis' talk, attacked Waiilatpu. According to Mary Ann Bridger (the young daughter of mountain man Jim Bridger), a lodger of the mission and eyewitness to the event, the men knocked on the Whitmans' kitchen door and demanded medicine. Bridger said that Marcus brought the medicine, and began a conversation with Tiloukaikt. While Whitman was distracted, Tomahas struck him twice in the head with a hatchet from behind and another man shot him in the neck.[28] The Cayuse men rushed outside and attacked the white men and boys working outdoors. Narcissa found Whitman fatally wounded; yet he lived for several hours after the attack, sometimes responding to her anxious reassurances. Catherine Sager, who had been with Narcissa in another room when the attack occurred, later wrote in her reminiscences that "Tiloukaikt chopped the doctor's face so badly that his features could not be recognized."[28]

Narcissa later went to the door to look out; she was shot by a Cayuse man. She died later from a volley of gunshots after she had been coaxed to leave the house.[29] Additional persons killed were Andrew Rodgers,[30] Jacob Hoffman, L. W. Saunders, Walter Marsh,[31] John[32] and Francis Sager,[33] Nathan Kimball,[34] Isaac Gilliland,[35] James Young,[36] Crocket Bewley, and Amos Sales.[37] Peter Hall, a carpenter who had been working on the house, managed to escape the massacre and reach Fort Walla Walla to raise the alarm and get help. From there he tried to get to Fort Vancouver but never arrived. It is speculated that Hall drowned in the Columbia River or was caught and killed. Chief "Beardy" tried in vain to stop the massacre, but did not succeed. He was found crying while riding toward the Waiilatpu Mission.[38]

The Cayuse took 54 missionaries as captives and held them for ransom, including Mary Ann Bridger and the five surviving Sager children. Several of the prisoners died in captivity, including Helen Mar Meek[39] and Louisa Sager, mostly from illness such as the measles. Henry and Eliza Spalding's daughter, also named Eliza, was staying at Waiilatpu when the massacre occurred. The ten-year-old Eliza, who was conversant in the Cayuse language, served as interpreter during the captivity.[40] She was returned to her parents by Peter Skene Ogden, an official of Hudson's Bay Company.[41]

One month following the massacre, on December 29, on orders from Chief Factor James Douglas, Ogden arranged for an exchange of 62 blankets, 62 cotton shirts, 12 Hudson's Bay rifles, 22 handkerchiefs, 300 loads of ammunition, 15 fathoms of tobacco for the return of the 49 surviving prisoners.[42] The Hudson's Bay Company never billed the American settlers for the ransom, nor did the latter ever offer cash payment to the company.

Trial

A few years later, after further violence in what would become known as the Cayuse War, some of the settlers insisted that the matter was still unresolved. The new governor, General Mitchell Lambertsen, demanded the surrender of those who carried out the Whitman mission killings. The head chief attempted to explain why they had killed the whites, and that the war that followed (the Cayuse War) had resulted in a greater loss of his own people than the number killed at the mission. The explanation was not accepted.

Eventually, tribal leaders Tiloukaikt and Tomahas, who had been present at the original incident, and three additional Cayuse men consented to go to Oregon City (then capital of Oregon), to be tried for murder. Oregon Supreme Court justice Orville C. Pratt presided over the trial, with U.S. Attorney Amory Holbrook as the prosecutor.[43][44] In the trial, the five Cayuse who had surrendered used the defense that it is tribal law to kill the medicine man who gives bad medicine.[3] After a lengthy trial, the Native Americans were found guilty; Hiram Straight reported the verdict as foreman of the jury of twelve.[44] Newly appointed Territorial Marshall Joseph Meek, seeking revenge for the death of his daughter Helen, was also involved with the process. The verdict was controversial because some observers believed that witnesses called to testify had not been present at the killings.

On June 3, 1850, Tiloukaikt, Tomahas, Kiamasumpkin, Iaiachalakis, and Klokomas were publicly hanged. Isaac Keele served as the hangman. An observer wrote, "We have read of heroes of all times, never did we read of, or believe, that such heroism as these Indians exhibited could exist. They knew that to be accused was to be condemned, and that they would be executed in the civilized town of Oregon city ... "[45]

Anniversary remembrance

How the West was Won: A Pioneer Pageant, was performed in Walla Walla, Washington on June 6–7, 1923, and again on May 28–29, 1924. Originally conceived by Whitman College President, Stephen Penrose, as an event marking the 75th anniversary of the Whitman Massacre, the Pageant quickly gained support throughout the greater Walla Walla community. It was produced as a theatrical spectacle that was allegorical in nature and spoke to prevalent social themes of the frontier period, such as manifest destiny. The Whitman Massacre was presented as a small but significant part of a production in four movements: "The White Man Arrives," "The Indian Wars," "The Building of Walla Walla," and "The Future." The production included 3,000 volunteers from Washington, Oregon, and Idaho.[46] The Pageant was directed by Percy Jewett Burrell.

"The pageant of today is the Drama of our Democracy!"[47] declared Burrell. He praised the merits of the pageant, citing "solidarity," "communal [artistry]," and "spirit." The pageant's success was due, in part to the popularity of the theatrical form during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which held certain commonalities with other spectacular events, such as world's fairs and the arcades.[48] These commonalities include a large number of actor/participants, multiple stage/tableaux settings, and the propagation of ideological concerns. The Pageant contributed to a narrative that divine providence had ensured the success of European settlers over Native Americans in the conquest of western lands.

Situated in Eastern Washington 250 miles east of the ports of Seattle and Portland, Walla Walla was not an easy location to access in 1923–24. But local businesses worked with the Chamber of Commerce to provide special train service to the area, which included "sleeping car accommodations for all who wish to join the party", for a round-trip fare of $24.38. Arrangements were made for the train to park near the amphitheater until the morning after the final performance, "thus giving the excursionists a hotel on wheels during their stay."[49]

The Automobile Club of Western Washington encouraged motorists to take the drive over Snoqualmie Pass because of good road conditions. "We have been informed that the maintenance department of the State Highway Commission is arranging to put scraper crews on all the gravel road stretches of the route next week and put a brand new surface on the road for the special benefit of the pageant tourists."[49] The Pageant brought 10,000 tourists to Walla Walla each year, including regional dignitaries such as Oregon Governor Walter E. Pierce and Washington Governor Louis F. Hart.[50]

See also

- Walla Walla expeditions, spread of disease which preceded the massacre

References

- Mann, Barbara Alice (2009). The Tainted Gift: The Disease Method of Frontier Expansion. ABC Clio.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Drury, Clifford M. "Marcus and Narcissa Whitman and the Opening of Old Oregon." Volume 1, Chapter 8. Seattle: Northwest Interpretive Association, 2005.

- "Defendants Request, Whitman Massacre Trial, 1851 (Transcript of original document)". Echoes of Oregon History Learning Guide. Oregon State Archives. Retrieved May 13, 2012.

- Whaley, Gray. Oregon and the Collapse of Illahee U.S. Empire and the Transformation of an Indigenous World, 1792-1859. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010. p. 94.

- Addis, Cameron. "The Whitman Massacre: Religion and Manifest Destiny on the Columbia Plateau, 1809-1858", Journal of the Early Republic 25, No. 2 (2005), pp. 221-258.

- Brouillet, J. B. A. Authentic Account of the Murder of Dr. Whitman and Other Missionaries, by the Cayuse Indians of Oregon, in 1847, and the Causes Which Led to That Horrible Catastrophe. 2nd ed. Portland, OR.: S.J. McCormick, 1869. pp. 23-24.

- Whitman, Marcus. "To Rev. Greene: May 5, 1837." Whitman Mission. November 11, 1841. Accessed September 17, 2015.

- Whitman, Marcus. To Rev. Greene: October 15, 1840. Whitman Mission. October 15, 1840. Accessed September 8, 2015.

- Narcissa Whitman to Rev. Mrs. H. K. W. Perkins, May 2, 1840. Whitman, Narcissa Prentiss. The Letters of Narcissa Whitman. Fairfield, WA: Ye Galleon Press, 1986.

- Whitman, Marcus. To Rev. Greene: November 11, 1841. Whitman Mission. November 11, 1841. Accessed September 8, 2015.

- Brouillet (1869), p. 27.

- Blanchet, Francis Norbert Historical sketches of the Catholic Church in Oregon, Portland, OR: 1878, p. 35.

- Whitman, Marcus. To Rev. Walker: December 27, 1839. Whitman Mission. December 27, 1839. Accessed September 17, 2015.

- Blanchet (1878), p. 93.

- Whitman, Marcus. To Rev. Greene: March 27, 1840. Whitman Mission. March 27, 1840. Accessed September 17, 2015.

- Whitman, Marcus. To Rev. Greene: October 29, 1840. Whitman Mission. October 29, 1840. Accessed September 17, 2015.

- American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (1845), pp. 212-213.

- American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (1845), p. 187.

- Whitman, Marcus. To Rev. Greene: October 5, 1838. Whitman Mission. October 5, 1838. Accessed September 17, 2015.

- Whitman, Marcus. To Rev. Greene: May 8, 1838. Whitman Mission. May 8, 1838. Accessed September 17, 2015.

- American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. Annual Report: Volumes 32-36. Boston: 1845. Vol. 33, p. 194.

- Brouillet (1869), p. 30.

- Robert Boyd. The Coming of the Spirit of Pestilence: Introduced Infectious Diseases and Population Decline among Northwest Coast Indians, 1774-1874. University of Washington Press, Seattle and London, 1999, pp. 146-148.

- Heizer, Robert Fleming. "Walla Walla Indian Expeditions to the Sacramento Valley," California Historical Society Quarterly, Vol. 21, No. 1 (1942), pp. 1-7.

- "Defendants Request, Whitman Massacre Trial, 1851 (Transcript of original document)". Echoes of Oregon History Learning Guide. Oregon State Archives. Retrieved May 13, 2012.

- Mann (2009).

- Mowry, William Augustus (1901). Marcus Whitman and the Early Days of Oregon. Silver, Burdett. p. 320.

That person (Rogers) then told the Indians that the doctor intended to poison them.

- Drury (2005) Vol. 2, pp. 250-252.

- Drury (2005) Vol. 2, pp. 256, 261-262.

- Drury (2005) Vol. 2, p. 262

- Drury (2005) Vol. 2, p. 253

- Drury (2005) Vol. 2, p. 252

- Drury (2005) Vol. 2, p. 257–258

- Drury (2005) Vol. 2, p. 265

- Drury (2005) Vol. 2, p. 254

- Drury (2005) Vol. 2, p. 269

- Drury (2005) Vol. 2, p. 287

- Drury (2005) Vol. 2, p. 263

- Drury (2005) Vol. 2, p. 337

- Drury (2005) Vol. 2, p. 305

- Drury (2005) Vol. 2, p. 328

- Drury (2005) Vol. 2, p. 321

- "The Whitman Massacre Trial: An indictment is issued". Oregon State Archives. Retrieved March 3, 2008.

- "The Whitman Massacre Trial: A Verdict is Reached". Oregon State Archives. Retrieved February 18, 2008.

- "A parallel for the Utes". The United States Army and Navy Journal, and Gazette of the Regular and Volunteer Forces. Vol. 17. New York: Publication Office, No. 39 Park Row, 1880. 242.

- Stephen Penrose, How the West was Won: A Pioneer Pageant, Walla Walla, Washington: 1923, Introduction

- Stephen Penrose, How the West was Won: A Pioneer Pageant, Walla Walla, Washington, 1923, To the People of the Pageant (Director's Introduction)

- The Arcades Project, Walter Benjamin, translated by Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin, Belknap Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1999

- "Seattle to Join Sister City in Big Celebration", Seattle Times, 18 May 1924

- Walla Walla Union Bulletin, "Visitors Crowd Into this City to View Pageant", May 29, 1924

- William Henry Gray, A History of Oregon, 1792–1849, drawn from personal observation and authentic information ... , Harris and Holman: 1870, pp. 464, MOA

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- National Park Service, Whitman Massacre

- The Whitman Massacre

- Mary Marsh Cason's – survivor account

- Matilda Sager's – survivor account

- Elam Young's account

- Walla Walla Treaty Council, 1855

- Addis, Cameron. "Whitman massacre". The Oregon Encyclopedia.

- Lansing, Robert B. "Whitman massacre". The Oregon Encyclopedia.