Wem

Wem is a small market town in Shropshire, England,[1] 9 miles (14 km) north of Shrewsbury on the rail line between that town and Crewe in Cheshire.

Wem | |

|---|---|

Clockwise from top: Wem High Street, Nobel Street, Church of St Peter and St Paul, The Old Wem Mill | |

Coat of arms  Emblem | |

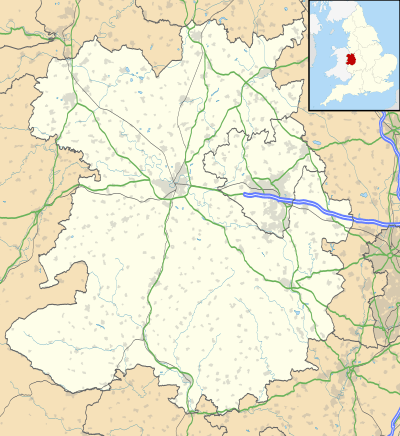

Wem Wem shown within Shropshire and England | |

| Coordinates: 52.8536°N 2.7267°W | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Constituent country | England |

| Region | West Midlands |

| Ceremonial county | Shropshire |

| Local government | Shropshire Council |

| Website | Wem Town Council |

| Norman Castle Town planned | c1066 |

| Market charter granted | 1202 |

| Seat | Edinburgh House |

| Government | |

| • Type | Town council |

| • Governing body | Wem Town Council |

| • UK Parliament | North Shropshire |

| • European Parliament | West Midlands |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1.41 sq mi (3.66 km2) |

| Elevation | 269 ft (82 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 6,100 |

| Demonym(s) | Wemian |

| Time zone | GMT |

| • Summer (DST) | BST |

| Post codes | |

| Area code(s) | 01939 |

| Police Force | West Mercia Police |

| Fire Service | Shropshire Fire |

| Ambulance Service | West Midlands |

| Website | https://www.wem.gov.uk/ |

The name of the town is derived from the Old English wamm, meaning a marsh, as marshy land exists in the area of the town. Over time, this was corrupted to form "Wem".[2]

As a caput of a barony and the centre of a large manor and parish Wem was a centre for justice and local government for centuries, and was the headquarters of the North Shropshire District Council until Shropshire became a unitary authority. From the 12th century revisions to the hundreds of Shropshire, Wem was within the North Division of Bradford Hundred until the end of the 19th century.[3]

According to Professor Richard Hoyle, Chairman of Victoria County History Shropshire, "Wem is an archetypal medieval-planned castle town and as such, can take its place alongside the best examples in England"[4]

History

Prehistory and Roman

The area now known as Wem is believed to have been settled prior to the Roman Conquest of Britain, by the Cornovii, Celtic Iron Age settlers: there is an Iron Age hillfort at nearby Bury Walls occupied over into the Roman period, and the Roman Road from Uriconium to Deva Victrix ran close by to the east at Soulton.[5]

Dark Ages

The 'Wem Hord', a collection of coins deposited in the post Roman period, was found in land in the Wem area in 2019.[6][7]

Norman and medieval periods

Weme was an Anglo-Saxon estate, which transitioned into a planned Norman castle-town established after the conquest, with motte-and-bailey castle, parish church and burgage plots.[8] The town is recorded in the Domesday Book[9] as consisting of four manors in the hundred of Hodnet.[10] The Domesday Book records that Wem was held by William Pantulf and comprised:

- Households: 4 villagers. 8 smallholders. 2 slaves.

- Land and resources: ploughland: 8 ploughlands. 1 lord's plough teams. 1 men's plough teams.

- Other resources: woodland 100 pigs.

with an annual value to lord: 2 pounds in 1086; up to 1 pound 7 shillings in 1066.

Plantulf fought at the Battle of Hastings under his superior lord Earl Rodger Stafford Castle and Wem was granted to him with a further 28 manors in the area bounded by Clive, Ellesmere, Tilley and Cresswell, with some of the manors within this area belonging to other lords (Prees to the Bishop of Lichfield, and Soulton to the King's Chapel in Shrewsbury Castle, for example). Plantulf refused to participate in an 1102 rebellion against King Henry 1 led by Robert de Belesme and assisted the crown defeating it, by marching with the king on Shrewsbury., during which the roads in the area were found to be bad, thickly wooded, providing cover for archers: 6000 foot soldiers cut down the woods and opened up the roads. Hugo Plantulf, a descendant of William, was Barron of Wem in the mid 1100s: he attended the court of Richard the Lion Heart, was Sheriff of Shropshire, and likely attended the Crusades with the king, certainly paying scutage to towards his ransom.[11]

The Norman town was probably enclosed by an earthwork: there is a record from the lord's steward of repairs to the town's enclosure in 1410, in which year the town had been "totally burnt and wasted by the Welsh rebels".[8] There is some speculation that the town had walls by the 1400s, as Samuel Garbet recorded an annotation to Fabyan's Chronicle that Wem "was totally burnt to the ground, with its walls and castle" in the reign of Henry VI.[12]

The supposed route of the walls or earthworks follows Noble Street, Wem Brook, the Roden and crossing the High Street between Leek Street and Chaple Street.

There were bars at the three entrances to the town, and a 1514 record exists of four men being employed to keep the bars on market days.[8]

There is some thought that a market was held from the days of Plantuf,[13] but King John certainly granted a charter in 1202.[2] Initially, the permission was for a Sunday market. This was subsequently revised, in 1351, to a Thursday: this followed a decree of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Simon Islip in the reign of Edward III that Sunday markets were banned. Wem's market day remains Thursday to this day.[14]

The manor was held by some of the great baronial families: including the Earls of Arundel, and the Lords Dacre, Bradford and Barnard and, after the 14th century the lord of the manor was not resident.[8]

Large common fields farmed in strips lay outside the town walls: Pool Meadows (waste ground by the river within the lord's demesne); Cross Field (lying toward Soulton, and thought to have been named for a wayside cross); Middle Field (part of which was later known as Leper Middle Field, giving an insight into medieval life); and Chapel Field (named after a chapel of ease on the Horton Road dedicated to St John which was suppressed in 1548). There was a Manorial Court House at Wem in which a twice yearly Court leet with grim the privilege of a gallows, hearing pleas including hue-and-cry, bloodshed.[11]

Tudor Period

In Henry VIII's reign Lord Dacre (d. 1563) began to fell Northwood, a task completed by the Countess of Arundel (d. 1630), his grand-daughter. Dacre also drained the Old Pool,work again completed by his grand-daughter.[15]

By 1561 the former castle enclosure was held at will by the Rector, John Dacre. Manor perquisites noted in 1589 show that there were two annual fairs where the lord took a toll on all goods worth above 12d. sold by strangers and tenants (but not burgagers) and the profits of the courts. In 1579 the lord's steward ruled that there should not be more than five alehouses in the township; however, unlicensed brewers were not prevented and were fined in number at each court leet.[8]

1600s

Civil war

In September 1642, during the English Civil War Charles I passed close by Wem en route from Chester to Shrewsbury at the invitation of the corporation of the town,[16] taking the route via Soulton and Lee Brickhurst, and early 1642 Royalists were staying in Wem. However, during the campaigns in Newbury and Glouster the town was planted with a Parliamentarian garrison. Under the supervision of Sir William Brereton a broad ditch four yards deep and wide and rampart, strengthened by a palisade made from timber cut from a felled 50 acre wood at Loppington was thrown up around the town to fortify it (some traces of this survive in the town). The route of this fortification was as follows: it began at a wooden tower on Soulton Road, just beyond the present station, from there it ran to "Shrewsbury Gate" crossing Well Walk and the bottom of Roden House garden; it than ran to the "Ellesmere Gate" where the stream crossed road; the earthworks continued along the back of Nobel Street to "Whitchurch Gate; on from there to "Drayton Gate" at 18 Aston Street and then back to the wooden tower. Many of the buildings beyond this rampart were destroyed in fortifying the town, to prevent them being of use to attackers.

The town was the seat of the Shropshire Committee until the fall of Royalist Shrewsbury in 1645, and was subject to an attack by Lord Capel, with a force comprising, according to H. Pickering (who served under Lord Capell) writing to the Duchess of Beaufort:

3 cannon, 2 drakes, one great mortarpiece that carried a 30ln. bullet, had 120 odd wagons and carriages laden with bread, biskett[sic], bare and other provisions and theire[sic] armye[sic] being formydable[sic] as consistynge[sic] of neer[sic] 5,000.[17]

Wem was not ready for the attack: the walls were not finished, the gates were not hinged, some of the guns on the ramparts were wooden dummies and the defending force consisted of only 40 male Parliamentarians; but then the local women rallied round positioning themselves in red coats in well chosen spots to scare the Royalists. So confident of success were the Royalist attackers that they only attacked on one side, approaching Wem only from Soulton Road, with the commander, Lord Cape, lightheartedly smoking his pipe half a mile from the town on that road.

And yet, the town held off the attackers. The resulting battle remembered in this couplet:

The women of Wem and a few musketeers, Beat the Lord Capel and all his Cavaliers.[18]

According to Brereton's report, royalist losses were heavy:

the great slaughter and execution which we performed upon the enemy when they set upon Wem. There being six cartloads of dead men carried away at one time, besides the wounded and it is said, there were fifteen found burried[sic] in one grave. Others were slayne[sic] and lefte[sic] in the open fields dead and unburyied[sic] whose naked bodies we saw miserably torne[sic] with the shott[sic]. and lyeing[sic] in the fields near the town, which wee[sic] gave orders to bee[sic] buryed[sic]... Little execution was done upon our men, we lost not above three in the town, a Major, one soldier and one boy[17]

The sword of a Cromwellian trooper was dug up at Wem in 1923, and a cannonball of the same period was found during construction work at the Grammar School.[11]

Restoration

In 1648 Hinstock, Loppington, and Wem were assessed for sale, and lands were sold from the manorial holdings throughout the 1650s. By 1665, when Daniel Wycherley bought the manor, the manorial property was much reduced from the holding it had been in 1648.[19]

Wem was held by Judge Jeffreys (1645–1689), known as the "hanging judge" for his willingness to impose capital punishment on supporters of the Duke of Monmouth. His seat was Lowe Hall at The Lowe, Wem. In 1683 he was made Baron Jeffreys of Wem.

Great Fire of Wem

On 3 March 1677, a fire destroyed many of the wooden buildings in the town, the event came to be known as the "Great Fire of Wem".[2][20]

1700s

The town was the childhood home of one of England's greatest essayists and critics, William Hazlitt (1778–1830). Hazlitt's father moved their family there when William was just a child. Hazlitt senior became the Unitarian Minister in the town[21] occupying a building on Noble Street that still stands. In 2008 the town held a 230th Anniversary Celebration of Hazlitt's Life and work for five days, hosted by author Edouard d'Araille who gave series of talks and conference about 'William of Wem'. William Hazlitt moved away from Wem in later life and ultimately died in London. John Astley, John Ireland,[22] and Joe Berks[23] all also grew up in the town.

By 1740 a workhouse existed in Wem, by 1777 it could house 20 inmates.[24] During this period, the Old Town Hall, while still the Town Hall, was used for sittings of the County Court.[25] The farming in this period saw an emphasis on dairy and grains. Other specializations included linen cloth.[26]

Victorian period

In the era of the stagecoach the town was served by two: 'The Hero' called at the Castle and the Union Stagecoach at the White Lion.[25]

Within the town the sweet pea was first commercially cultivated, under the variety named Eckford Sweet Pea, after its inventor, nursery-man Henry Eckford. He first introduced a variety of the sweet pea in 1882, and set up in Wem in 1888, developing and producing many more varieties.

There is a road to signify the Eckford name, called Eckford Park (within Wem). Each year, the Eckford Sweet Pea Society of Wem held a sweet pea festival until 2019 when the last festival was. In Victorian times, the town was known as "Wem, where the sweet peas grow".

20th century

Several public buildings built in the early 20th century used the Arts and Crafts style: the Morgan Library building, the old post office and the current town hall building are examples.

First World War

Fifty-five men of Wem are recorded as having fallen serving their country in the First World War. The town's war memorial was dedicated in 1920.[27]

Second World War

In 1940 Anna Essinger (1879–1960), a German Jewish educator, evacuated [28] her boarding school, Bunce Court School from Otterden, in Kent to Trench Hall, near Wem. She facilitated Kindertransport.[29]

The US created a storage facility at Aston Park estate on 14 December 1942. The facility was later converted to a prisoner of war camp, and was used for that purpose until 1948.[30]

Post War

Wem was struck by an F1/T2 tornado on 23 November 1981, as part of the record-breaking nationwide tornado outbreak on that day.[31]

In November 1995 the town hall suffered a catastrophic fire.[32] It reopened after repair, renewal, and redesign in 2000.[33][34]

21st century

From 2002 to 2019 the Morgan Library building was leased to 'Mythstories', which styles itself as the world's first museum of storytelling.[35] Wem is a Transition Town.[36]

Legends

Secret tunnels

There is said to have been a tunnel from the cellars under the castle mound to the building formerly known as "The Moathouse", and then on under Mill Street to Roden House, the former rectory, and there are blocked doorways in the cellars of both of these houses.[11]

Wem ghost

In 1995 an amateur photographer photographed a blaze which destroyed Wem Town Hall; the photo appeared to show the ghostly figure of a young female in a window of the burning building, dressed in 'old-fashioned' clothes.

Although the photographer (who died in 2005) denied forgery, after his death it was suggested that the girl in his photo bore a 'striking similarity' with one in a postcard of the town from 1922.[37][38]

Treacle Mines

Wem is reputed to have "treacle mines"—while It is not possible to mine treacle. Two explanations have been offered for this legend: (a) that a confectioners shop, despite the rationing and food shortages of the Second World War was apparently always in stock of candy; alternatively (b) the byproduct of the tanning industry within the town was considered to look a lot like treacle.[39]

Coat of arms and flag

The Wem Town Council use arms which are the shield of Shropshire, with a phoenix crest, with the shield laid over of an axe and a scythe.

Economy

The pre-modern economy of the town was based on agriculture and forestry and the processing of its output. Brewing, initially a cottage industry, was carried out in Wem as early as 1700, when Richard Gough wrote of a contemporary in his History of Myddle a Latin aphorism he translated: Let slaves admire base things, but my friend still/My cup and can with Wem's stoute ale shall fill.[40]

By 1900[41] a Shrewsbury and Wem Brewery Company traded on a widespread scale after acquiring the brewery in Noble Street previously run by Charles Henry Kynaston.[42] The company was taken over in turn by Greenall Whitley & Co Ltd[43] but the brewery was closed in 1988.[44] From 1986 to 1989 the brewery served as the shirt sponsor for Shrewsbury Town.[45]

There is a mid-sized industrial estate out to the east of the town.

Governance

Wem was historically the centre of a large parish, which became a civil parish in 1866.

In 1900 the outer parts of the parish were separated to form the civil parish of Wem Rural, and the town itself became the civil parish of Wem Urban, coextensive with Wem Urban District. In 1967 the urban district was abolished and became part of North Shropshire Rural District.[46] From 1974 to 2009 it was part of North Shropshire district.

The parish council of Wem Urban has exercised its right to call itself a town council.

The electoral ward of Wem for the purposes of elections to Shropshire Council also covers part of Wem Rural parish. The population of this ward at the 2011 Census was 8,234.[47]

Geography

The River Roden flows to the south of the town.

The Shropshire Way long distance waymarked path passes through Wem.

Culture and community

Recreation areas

There are recreation areas at the Wem Recreation Ground[48] and the Millennium Green (Wem Millennium Green being the smallest such green in the country).[49]

Sport and Clubs

Sports clubs within the town include:

- Wem Town Football Club

- Wem Cricket Club[50]

- Wem Tennis Club

- Wem United Services Bowling Club

- Wem Bowling Club

- Wem Albion Bowling Club

Clubs and societies include:

- Wem Amateur Dramatics Society (established 1919)

Wem Amateur Dramatics Society Building: former Apostolic Chapel acquired by the society after 1995 town hall fire

Wem Amateur Dramatics Society Building: former Apostolic Chapel acquired by the society after 1995 town hall fire - Sweetpea society

- Rotary Club of Wem and District

- Wem Sports and Social Club

- The Senior Club

- Wem & District Garden Club

- The United Services Club[51]

- Wem Jubilee Band (established 1977, with origins on the 1930s)[52]

Events

Each year Wem holds a traditional town carnival which is held on the first Saturday of September, as well as the Sweet Pea Festival on the third weekend of July. Wem Vehicles of Interest Rally & Grand Parade also runs alongside the Sweet Pea Festival on the Sunday.[53]

A Wem 10 km running race was instituted in 2019.[54]

There is a Wem Transport show annually in July.[55]

Religious life

Within the town there are four main churches:

Transport

Rail

The Crewe and Shrewsbury Railway was completed in 1858, and Wem was connected to national rail services from this time.[60]

The town has a small railway station located on the Welsh Marches Line. All services are operated by Transport for Wales. The majority of services that call at the station are between Shrewsbury and Crewe, however, some long-distance services to Manchester Piccadilly, Cardiff Central, Swansea, Carmarthen and Milford Haven also stop at the station during peak times.

Canals

The canal network came closest to Wem at Whixhall and Edstaston; the Ellesmere canal was closed to navigation by Act of Parliament in 1944.[61]

Bus

The town is served by the 511 bus route, operated by Arriva Midlands North, which runs between Shrewsbury and Whitchurch. Some services terminate in Wem and do not continue to Whitchurch.

| Bus operator | Route | Destination(s) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arriva Midlands North | 511 | Shrewsbury → Hadnall → Clive → Wem → Prees → Whitchurch | Some services terminate in Wem.[64] |

Education

St Peters is a Church of England primary school in Wem.

Thomas Adams School is a state-funded secondary school, established in 1650. This was an independent grammar school until 1976, at which point it merged with Wem Modern School to form a comprehensive school. It also has a Sixth Form College on site.

A number of private schools have operated in Wem over the centuries. William Hazlitt's father ran a 'model crammer for the dissenting rationalist' in the town, the 'Mrs Swanswick's School' ran from the late 1700s to the 1840s and one of its headmasters, Joseph Pattison, took a leading role in founding British Schools to educate children from less advantaged families. A further six private schools operated our of Wem over time.[8]

Local landmarks and attractions

- Fenn's, Whixall and Bettisfield Mosses National Nature Reserve

Soulton Long Barrow, modern revival of prehistoric monument building east of Wem

Soulton Long Barrow, modern revival of prehistoric monument building east of Wem - Hodent Hall Gardens

- Soulton Hall and Soulton Long Barrow

- Whixall Marina

- Hawkstone Park

Twin towns

Since 1978, Wem has been twinned with Fismes[66] in France, after which is named a road in Wem, Fismes Way.[67]

Notable townsfolk

.jpg)

- Judge Jeffreys

- Anna Essinger

- William Hazlitt

- Sir Thomas Adams, 1st Baronet (1586 in Wem – 1667/1668) Lord Mayor of the City of London[68] and MP for the City of London from 1654–1655 and 1656–1658.

- Philip Holland (1721 in Wem – 1789) nonconformist minister.[69]

- John Astley (1724 in Wem – 1787) portrait painter[70] and amateur architect

- Edward Whalley-Tooker (1863 in Wem – 1940) cricketer,[71] played for Hampshire.

- Peter Jones (1920 in Wem – 2000) actor,[72] screenwriter and broadcaster[73] and for 29 years a regular contestant on the panel game Just A Minute

- Peter Vaughan (1923 in Wem – 2016) character actor,[74] known for his role as Grouty in the sitcom Porridge

- Sybil Ruscoe (born 1960 in Wem) radio[75] and television presenter [76]

- Greg Davies (born 1968) stand-up comedian, actor[77] was brought up and went to Thomas Adams School in Wem

- Neil Faith (born 1981) semi-retired English professional wrestler,[78] went to Thomas Adams School in Wem

Further reading

- Woodwood, Iris "A Story of Wem". 1952, Wem Urban Di struct Council, Wildings of Shrewsbury.

- Everard, Judith et al "Victoria County History Shropshire – Wem", 2019.

- The History of Wem by Samuel Garbet (1818)

References

- OS Explorer Map 241, Shrewsbury, Wem, Shawbury & Baschurch. ISBN 978-0-319-46276-8

- "History of Wem". Wem. Retrieved 2 July 2008.

- "Bradford Hundred - British History Online".

- "Wem History Day 'huge success' as visitors learn of town's rich past". Whitchurch Herald. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- "Archaeology LIDAR | Soulton Hall". www.soultonhall.co.uk. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- Austin, Sue. "One of rarest Dark Ages finds - the Wem hoard - is declared treasure". www.shropshirestar.com. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- "'Wem Hoard' of Roman hacksilver declared treasure at Coroner's inquest last week". Shropshire Council Newsroom. 9 September 2019. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- Everard, Judith, 1963-. Wem. London. ISBN 978-1-912702-08-4. OCLC 1079338551.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Wem | Domesday Book". opendomesday.org. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- Powell-Smith, Anna. "Wem - Domesday Book".

- Woodward, Iris (1952). The Story of Wem. Wildings of Shrewsbury. pp. 23–25.

- Samuel, Garbett. The History of Wem; And [Other] ... Townships [In Shropshire].

- www.wemlocal.org.uk http://www.wemlocal.org.uk/wemmap/market.htm. Retrieved 9 May 2020. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Kreft, Marie. (2016). Bradt Slow Travel Shropshire: Local, Characterful Guides to Britain's Special Places. Globe Pequot Pr. ISBN 978-1-78477-006-8. OCLC 949921860.

- "Domesday Book: 1540-1750 | British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- Fisher, George William; Hill, John Spencer (1899). Annals of Shrewsbury School. University of California Libraries. London : Methuen.

- "Shropshire's History Advanced Search | Shropshire's History Advanced Search". Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- www.shropshiretourism.co.uk, Shropshire Tourism (UK) Ltd-. "Wem in North Shropshire". North Shropshire. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- "Domesday Book: 1540-1750 | British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- "Great Fires of Newport & Wem". shropshirehistory.com. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- "Wem". Shropshire Routes to Roots. Retrieved 2 July 2008.

- "John Ireland - National Portrait Gallery". www.npg.org.uk. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- "Local Bygones: Wem boxer Joe Berks in training for match". Border Counties Advertizer. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- "The Workhouse in Wem, Shropshire (Salop)". www.workhouses.org.uk. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- www.wemlocal.org.uk http://www.wemlocal.org.uk/wemmap/1830.htm. Retrieved 9 May 2020. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Domesday Book: 1540-1750 | British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- "Wem Memorial Cross". Imperial War Museums. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- The Guardian, 18 July 2003, Anna's children retrieved 17 March 2018

- Rowden, Nathan. "Kindertransport: The Shropshire school with a remarkable history". www.shropshirestar.com. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- "Shropshire's History Advanced Search | Shropshire's History Advanced Search". Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- http://www.eswd.eu/cgi-bin/eswd.cgi

- www.wemlocal.org.uk http://www.wemlocal.org.uk/wempast/histcin/cinema.htm. Retrieved 6 May 2020. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Homepage". NRTF. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- "History". Wem Town Hall. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- "Mythstories museum of myth and fable". www.mythstories.com. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- Foregate, Abbey; Shrewsbury; Shropshire; Sy2 6nd (6 February 2012). "Meeting of Wem and Shawbury Local Joint Committee on Monday, 6th February, 2012". shropshire.gov.uk. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- "Ghost picture mystery resolved".

- "Has the mystery of the 'Wem Ghost' photograph finally been solved? - The Times".

- "Three things you wanted to know about". BBC News. 9 December 2016. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- Woodward, Iris (1976). The Story of Wem and its Neighbourhood. Wilding's, Shrewsbury. p. 18.Gough's book was not published until the 19th century.

- Kelly's Directory of Shropshire. Kelly's. 1900. pp. 269, 333.

- Kelly's Directory of Shropshire. Kelly's. 1895. pp. 253, 312.

- Woodward, Iris. The Story of Wem and its Neighbourhood. p. 114.

- "End of Era for Brewery". Shropshire Star. 22 July 1987.

- "Shrewsbury Town - Historical Football Kits".

- "Wem Rural CP through time - Census tables with data for the Parish-level Unit".

- "Ward population 2011". Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- "Recreation Ground & Play Areas | Wem Town Council". www.wem.gov.uk. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- "Wem Millennium Green Chapel". wemmillenniumgreen. 24 December 2018. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- Cooper, Dave. "Wem Cricket Club are crowned champions". www.shropshirestar.com. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- Etherington, Linda (2014). "The Wemian" (PDF). The Wemian.

- "Wem Jubilee Band - Home". wemjubileeband.btck.co.uk. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- Wall, Amy. "Crowds turn out for annual Wem Carnival - PICTURES". www.shropshirestar.com. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- "Wem 10K Road Race - Wem 10k Road Race - Wem 10k Road Race - runbritain". www.runbritain.com. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- Austin, Sue. "Crowds set to have wheely good time at Wem transport show". www.shropshirestar.com. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- "St Peter & St Pauls, Wem". www.wemcofe.co.uk. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- "Home". Wem Baptist Church. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- "Wem Churches near Shrewsbury, Shropshire".

- http://search3.openobjects.com/kb5/shropshire/cd/view.page?record=LQLE5deSKGE

- www.wemlocal.org.uk http://www.wemlocal.org.uk/wemmap/1870.htm. Retrieved 9 May 2020. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - www.wemlocal.org.uk http://www.wemlocal.org.uk/wempast/industry/canal.htm. Retrieved 8 May 2020. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Shropshire Aero Club |". www.flysac.co.uk. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- "Sleap Airfield installs LED runway lighting from Smooth Aviation". Pilot. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- "511 Shrewsbury to Whitchurch bus timetable". Arriva North.

- Much Wenlock Town Council website retrieved 19 January 2019

- "Twin towns".

- "Location Map".

- Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, Volume 01, Adams, Thomas (1586-1667) retrieved 17 March 2018

- Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, Volume 27, Holland, Philip retrieved 17 March 2018

- John Astley on Artnet retrieved 17 March 2018

- ESPN cricinfo Database retrieved 17 March 2018

- IMDb Database retrieved 17 March 2018

- "TV Comedy People: Peter Jones". British TV Resources. Retrieved 2 July 2008.

- IMDb Database retrieved 17 March 2018

- IMDb Database retrieved 17 March 2018

- Sybil Ruscoe Media, Sybil Ruscoe retrieved 17 March 2018

- IMDb Database retrieved 17 March 2018

- Online World Of Wrestling, Profile, Neil Faith retrieved 17 March 2018

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wem. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Wem. |

- Wem Town Hall – history, events, information

- Wem Carnival photos

- The Haunting of Wem Town Hall

- Old Pictures of Wem