Weismann barrier

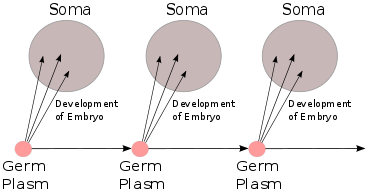

The Weismann barrier, proposed by August Weismann, is the strict distinction between the "immortal" germ cell lineages producing gametes and "disposable" somatic cells, in contrast to Charles Darwin's proposed pangenesis mechanism for inheritance.[1][2] In more precise terminology, hereditary information moves only from germline cells to somatic cells (that is, somatic mutations are not inherited).[3] This does not refer to the central dogma of molecular biology, which states that no sequential information can travel from protein to DNA or RNA, but both hypotheses relate to a gene-centric view of life.[4]

Weismann set out the concept in his 1892 book Das Keimplasma: eine Theorie der Vererbung (The Germ Plasm: a theory of inheritance).[5]

The Weismann barrier was of great importance in its day and among other influences it effectively banished certain Lamarckian concepts: in particular, it would make Lamarckian inheritance from changes to the body (the soma) difficult or impossible.[6] It remains important, but has however required qualification in the light of modern understanding of horizontal gene transfer and some other genetic and histological developments.[7] The use of this theory, commonly in the context of the germ plasm theory of the late 19th century, before the development of better-based and more sophisticated concepts of genetics in the early 20th century, is sometimes referred to as Weismannism.[8] Some authors call Weismannist development (either preformistic or epigenetic) that in which there is a distinct germ line, differently of somatic embryogenesis.[9] This type of development is correlated with the evolution of death of the somatic line.

Plants and basal animals

In plants, genetic changes in somatic lines can and do result in genetic changes in the germ lines, because the germ cells are produced by somatic cell lineages (vegetative meristems), which may be old enough (many years) to have accumulated multiple mutations since seed germination, some of them subject to natural selection.[10] Likewise, basal animals such as sponges (Porifera) and corals (Anthozoa) contain multipotent stem cell lineages, that give rise to both somatic and reproductive cells. The Weismann barrier appears to be of a more recent evolutionary origin.[11]

See also

- Alternatives to evolution by natural selection

- Baldwin effect – Effect of learned behavior on evolution

- Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance

- Lamarckism – Hypothesis that an organism can pass on characteristics that it has acquired through use or disuse during its lifetime to its offspring

- Pangenesis – former theory that inheritance was based on particles from all parts of the body

References

- Geison, G. L. (1969). "Darwin and heredity: The evolution of his hypothesis of pangenesis". J Hist Med Allied Sci. XXIV (4): 375–411. doi:10.1093/jhmas/XXIV.4.375. PMID 4908353.

- You, Yawen (26 January 2015). "The Germ-Plasm: a Theory of Heredity (1893), by August Weismann". The Embryo Project Encyclopedia (Arizona State University). Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- Gauthier, Peter (March–May 1990). "Does Weismann's Experiment Constitute a Refutation of the Lamarckian Hypothesis?". BIOS. 61 (1/2): 6–8. JSTOR 4608123.

- De Tiege, Alexis; Tanghe, Koen; Braeckman, Johan; Van de Peer, Yves (January 2014). "From DNA- to NA-centrism and the conditions for gene-centrism revisited". Biology & Philosophy. 29 (1): 55–69. doi:10.1007/s10539-013-9393-z.

- Weismann, August (1892). Das Keimplasma: eine Theorie der Vererbung. Jena: Fischer.

- Romanes, George John (1893). An examination of Weismannism. Open Court. OL 23380098M.

- Lindley, Robyn A. "How Mutational and Epigenetic Changes Enable Adaptive Evolution". G. I. T. Laboratory Journal.

- Romanes, George John (1893). An examination of Weismannism. Chicago: Open court. OL 23380098M.

- Ridley, Mark (2004). Evolution (3rd ed.). Blackwell. pp. 295–297.

- Whitham, T.G.; Slobodchikoff, C.N. (1981). "Evolution by individuals, plant-herbivore interactions, and mosaics of genetic variability: The adaptive significance of somatic mutations in plants". Oecologia. 49 (3): 287–292. doi:10.1007/BF00347587. PMID 28309985.

- Radzvilavicius, Arunas L.; Hadjivasiliou, Zena; Pomiankowski, Andrew; Lane, Nick (2016-12-20). "Selection for Mitochondrial Quality Drives Evolution of the Germline". PLOS Biology. 14 (12): e2000410. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.2000410. ISSN 1545-7885. PMC 5172535. PMID 27997535.