Water supply and sanitation in Hong Kong

Water supply and sanitation in Hong Kong is characterized by water import, reservoirs and treatment infrastructure. Though multiple measures were made throughout its history, providing an adequate water supply for Hong Kong has met with numerous challenges because the region has few natural lakes and rivers, inadequate groundwater sources (inaccessible in most cases due to the hard granite bedrock found in most areas in the territory), a high population density, and extreme seasonable variations in rainfall. Thus nearly 80 percent of water demand is met by importing water from mainland China, based on a longstanding contract.[1] In addition, freshwater demand is curtailed by the use of seawater for toilet flushing, using a separate distribution system.[2] Hong Kong also utilize the usage of reservoirs and water treatment plants to maintain its source of clean water through times.

History

Water rationing

Until 1964 water rationing - the act of limiting water usage for each households by water providers - was a constant reality for Hong Kong residents, occurring more than 300 days per year. The worst crisis occurred in 1963–64 when water was delivered only every 4 days for 4 hours each time. The territory, which was under British colonial administration, then embarked on a three-pronged approach to supply water to an increasing population. (Hong Kong's population increased from 1.7 million in 1945 to about 6 million in 1992.) The strategy involved seawater flushing, the construction of larger freshwater reservoirs in bays that used to be covered by the sea, and water imports from mainland China.[3]

Seawater flushing

In 1955 seawater was first used to flush toilets in a pilot scheme. This was followed by installation of seawater flushing systems in all new houses and in selected districts beginning in 1957.[4] In 1960 legislation was introduced to promote seawater flushing on a larger scale, followed by substantial investments in a separate network. However, the system was unpopular due to the need to build a separate plumbing network in each house. Seawater initially was sold, but from 1972 on it was provided for free and the costs of the system were recovered through the drinking water tariff. In 1991, about 65 percent of Hong Kong's households used seawater for flushing. By 1999, the number of conforming households had increased to 79 percent.[5]

Freshwater reservoirs in the sea

In 1957 construction began on the first dam that would close off a natural sea bay and create the Shek Pik Reservoir. The reservoir was built to store freshwater that previously had been "lost to the sea" during the rainy season. The reservoir was completed in 1963. The completion of Shek Pik reservoir was followed by the construction of two larger reservoirs of the same type. After the Plover Cove Reservoir was completed in 1968, water rationing was discontinued until 1977. With the completion of the High Island Reservoir in 1978, continuous water supply was re-established. Water rationing was renewed for the last time in 1980–81. Between 1965 and 1982 water had to be rationed seven times, often for many months with interruptions of up to 16 hours per day. To maintain Hong Kong's competitiveness, rationing was imposed only on residential users. Industry, the city's main water user, was exempted from rationing. The need for rationing was finally overcome in 1982 thanks to water imports.[3]

Water imports

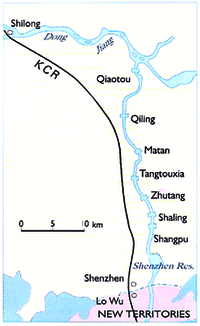

In 1960 Hong Kong began importing water from outside its borders through the Dongjiang – Shenzhen (Dongshen) Water Supply Scheme. After many extensions and upgrades the current system consists of a pipeline from Qiaotou Town of Dongguan to a reservoir in Shenzhen next to Hong Kong. Water imports from the Pearl River have increased gradually from 23 million cubic meters per year (under a 1960 agreement) to 1100 million cubic meters per year (under a fifth agreement signed in 1989). Water imports thus played a crucial role in alleviating Hong Kong's water crisis, accounting for 70 percent of the territory's water supply in 1991. The People's Republic of China has never exercised the "water weapon" in its relationship with Hong Kong. China needed foreign exchange and between 1979 and 1991 alone Hong Kong paid China almost 4 billion Hong Kong Dollars (about US$500 million applying the 1991 exchange rate) for water imports.[3]

Desalination

Desalination was a source of water in Hong Kong between 1975 and 1981. A large desalination plant was commissioned in Lok on Pai in 1975, but was decommissioned again in 1981 because its operation was more expensive than importing water from Dongjiang.[5] Another pilot desalination plant utilized reverse osmosis in Tuen Mun in Hong Kong during the year of 2004, but this plant lasted only one year. This plant was made as an experiment to witness the efficiency of reverse osmosis. Desalination is an intriguing topic that would definitely increase the rate at which clean water can be supplied as well as help prevent the overuse of water pipes for transportation, but it is an expensive process that currently does not yield too many benefits.[6]

Protecting raw water quality

The pollution of raw water supplied to Hong Kong became an increasing concern that triggered a variety of activities designed to protect the quality of raw water. In 1998 the intake of the water pipeline was moved further upstream on the Dongjiang River where water quality was better. In 2003 an 83 km dedicated aqueduct was completed, thus reducing the vulnerability of the supply to pollution. Additionally, wastewater treatment plants were constructed in settlements in the Dongjiang basin and polluting industries were removed, thus protecting the water at the source.[7] In 2006 a Water Supply Agreement was signed with Guangdong Province for a "flexible" supply of Dongjiang water.[4] The agreement allows for less water to be withdrawn when reservoirs in Hong Kong are full, and more water to be withdrawn in times of drought, while the annual payment remains the same. Under the new agreement, Hong Kong paid fixed lump sums of HK$2,959 million, HK$3,146 million and HK$3,344 million for 2009, 2010 and 2011 respectively.[8]

Total water management

In 2003 the government of Hong Kong announced what it called a "total water management programme". In 2005 a study was commissioned and the results were broadly discussed. Based on the study the government reaffirmed its approach to water management, but also started new initiatives concerning leakage reduction, water conservation, greywater reuse, rainwater harvesting, as well as pilots for the reuse of reclaimed water and desalination. For example, the government plans to provide reclaimed water from Shek Wu Hui Sewage Treatment Works for consumers in Sheung Shui and Fanling for toilet flushing and other non-potable uses, as well as pilot desalination plants in Tuen Mun and Ap Lei Chau.[9]

Desalination comeback

Because the price of imported water increased from $1 to $3 per cubic meter, the Hong Kong authorities announced in 2011 that the government would build a 50,000 cubic meter per day seawater desalination plant. The plant will allow greater resiliency against droughts that may become more severe due to climate change.[10]

Sources of water

Hong Kong's three main sources of water are supplied from Guangdong Province; internal freshwater sources stored in reservoirs; and seawater used for flushing toilets. Dongjiang is Hong Kong's major source of water. The designed maximum capacity of the supply system is 1.1 billion cubic metres per annum. The supply contract, costing HK$2 billion a year, has helped the city's economy grow without the interruption caused by water shortages, although the payment constitutes only 0.15 percent of Hong Kong's HK$1.3 trillion gross domestic product. About one-third of Hong Kong's 1,098 square kilometres has been developed as water catchments including reservoirs behind dams on land and three 'reservoirs in the sea', the Shek Pik Reservoir, the Plover Cove Reservoir and the High Island Reservoir.

An interesting facet of the waterworks is the seawater supply system with its separate networks of distribution mains, treatment facilities for screening and disinfection, pumping stations and service reservoirs. Eighty (80) percent of the population, including nearly all housing estates in Hong Kong Island and other densely populated districts, receive sea water for flushing. Some remote districts in the New Territories and some outlying islands do not use the system.[3] In 2010, an average of about 740,000 cubic metres of seawater was supplied each day,[11] up from 330,000 cubic meters each day in 1990/91. Seawater is used to flush toilets and accounts for about 22 percent of total water use in 2008–09.

Consumption

More than 70 percent of Hong Kong's water is used by industry and services, particularly the textile, metal-working and electronics sectors in manufacturing, hotels and restaurants in services.[3]

All figures are in million cubic metres

| Fresh Water | 2003 – 2004 | 2004 – 2005 | 2005 – 2006 | 2006 – 2007 | 2007 – 2008 | 2008 – 2009 |

| Annual | 963.99 | 954.62 | 966.92 | 963.59 | 950 | 957.31 |

| Daily Average | 2.63 | 2.62 | 2.65 | 2.64 | 2.60 | 2.62 |

| Highest Daily | 2.91 | 2.79 | 2.82 | 2.84 | 2.81 | 2.86 |

| Seawater | 2003 – 2004 | 2004 – 2005 | 2005 – 2006 | 2006 – 2007 | 2007 – 2008 | 2008 – 2009 |

| Annual | 244.31 | 259.83 | 261.63 | 261.66 | 274.23 | 271.08 |

| Daily Average | 0.67 | 0.71 | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.75 | 0.74 |

Water infrastructure

Hong Kong's water infrastructure consists of the following water treatment plants, pumping stations and reservoirs.

Water treatment

The supply is fully treated by chemical coagulation, sedimentation (at most treatment works), filtration, pH value correction, chlorination and fluoridation. The water is soft in character and conforms in all respects – both chemically and bacteriologically – to standards for drinking water set by the World Health Organization. Residents often prefer to boil the water before drinking, but this is generally not necessary.[12]

The main water treatment plants are:

- Sha Tin Water Treatment Works, the largest water treatment works in Hong Kong in terms of daily output capacity[13]

- Pak Kong

- Au Tau

- Tsuen Wan

- Tuen Mun

- Tai Po

- Yau Kom Tau

- Ma On Shan

- Ngau Tam Mei

Pumping Stations

- Muk Wu No.2 & No. 3

- Tai Po Tau, Tai Po Tau No.2, No.3 & No.4

- Tai Mei Tuk & Tai Mei Tuk No.2

- Harbour Island

Reservoirs

The total storage capacity of Hong Kong's reservoirs is 586 million cubic meters. The reservoirs and their storage capacities are tabulated below:

| Reservoir (Year on reservoir) | Reservoir supply storage m³ |

| Pok Fu Lam (2 Res.) 1863 & 1877 | 260,000 |

| Tai Tam 1888 | 1,490,000 |

| Tai Tam Byewash 1904 | 80,000 |

| Tai Tam Intermediate 1907 | 686,000 |

| Kowloon 1910 | 1,578,000 |

| Tai Tam Tuk 1917 | 6,200,000 |

| Shek Lei Pui 1925 | 439,000 |

| Kowloon Reception 1926 | 121,000 |

| Aberdeen (2 Res.) 1931 | 1,210,000 |

| Kowloon Byewash 1931 | 800,000 |

| Shing Mun (Jubilee) 1937 | 13,600,000 |

| Tai Lam Chung 1957 | 20,490,000 |

| Shek Pik 1963 | 24,000,000 |

| Lower Shing Mun 1965 | 3,980,000 |

| Plover Cove 1973 | 230,000,000 |

| High Island 1978 | 273,000,000 |

Sanitation

There are a total of 68 sewage treatment facilities in Hong Kong, including 41 in Hong Kong Island, Kowloon and Outlying Islands and 27 in the New Territories.[14] One of the largest facilities is the Sha Tin Sewage Treatment Works covering an area of 28 hectares. It was commissioned in three stages in 1982, 1986 and 2004.

Institutional framework

The Water Supplies Department collects, stores, purifies and distributes potable water to consumers, and provides adequate new resources and installations to maintain a satisfactory standard of water supply. The department also supplies seawater for flushing toilets. The Drainage Services Department is responsible for sanitation.

See also

References

- Hartley, Kris; Tortajada, Cecilia; Biswas, Asit K. (1 September 2018). "Political dynamics and water supply in Hong Kong". Environmental Development. 27: 107–117. doi:10.1016/j.envdev.2018.06.003. ISSN 2211-4645.

- Lee, N. K. (2013). "The Changing Nature of Border, Scale and the Production of Hong Kong's Water Supply System since 1959". International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 38 (3): 903–921. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12060.

- Chau, K.W. (1993). "Management of limited water resources in Hong Kong". International Journal of Water Resources Development. 9 (1): 68–72. doi:10.1080/07900629308722574.

- "History of Water Supply in Hong Kong (1946–2007)" (PDF). Total Water Management. Water Supply Department. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- Government of Hong Kong. "Waterworks of a Century". Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- Yue, Derek P. T.; Tang, S. L. (2011). "Sustainable strategies on water supply management in Hong Kong". Water and Environment Journal. 25 (2): 192–199. doi:10.1111/j.1747-6593.2009.00209.x. ISSN 1747-6593.

- Water Supplies Department. "Dongjiang Raw Water". Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- Government of Hong Kong Press Release (7 December 2008). "Agreement ensures stable supply of Dongjiang Water to Hong Kong". Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- "Total Water Management" (PDF). Water Supply Department. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- HK Magazine (27 October 2012). "A New Desalination Plant in Hong Kong". Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- Water Supply Department. "Seawater for flushing". Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- "Water Supplies Department, Water Quality FAQ".

- Water Supplies Department: Sha Tin Water Treatment Works

- Drainage Services Department. "List of Sewage Treatment Facilities". Retrieved 9 November 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Water supply in Hong Kong. |

- Hong Kong Water Supplies Department

- Drainage Services Department

- Hong Kong Environmental Protection Department: Water