Water supply and sanitation in Sub-Saharan Africa

Although access to water supply and sanitation in Sub-Saharan Africa has been steadily improving over the last two decades, the region still lags behind all other developing regions. Access to improved water supply had increased from 49% in 1990 to 68% in 2015 [1], while access to improved sanitation had only risen from 28% to 31% in that same period. Sub-Saharan Africa did not meet the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs, 1990–2015) of halving the share of the population without access to safe drinking water and sanitation between 1990 and 2015.[2] There still exists large disparities among Sub-Saharan African countries, and between the urban and rural areas. The MDGs set International targets to reduce inadequate Water Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) coverage and now new targets exist under the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs, 2016–2030). The MDGs called for halving the proportion of the population without access to adequate water and sanitation, whereas the SDGs call for universal access, require the progressive reduction of inequalities, and include hygiene in addition to water and sanitation. Particularly, Sustainable Development Goal SDG6 focuses on ensuring availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all.[3]

Usually, water is provided by utilities in urban areas and municipalities or community groups in rural areas. Sewerage networks are not common and wastewater treatment is even less common. Sanitation is often in the form of individual pit latrines or shared toilets. 70% of investments in water supply and sanitation in Sub-Saharan Africa is financed internally and only 30% is financed externally (2001–2005 average). Most of the internal financing is household self-finance ($2.1bn), which is primarily for on-site sanitation such as latrines. Public sector financing ($1.2bn) is almost as high as external financing (US$1.4bn). The contribution of private commercial financing has been negligible at $10 million only.

Access

General trends

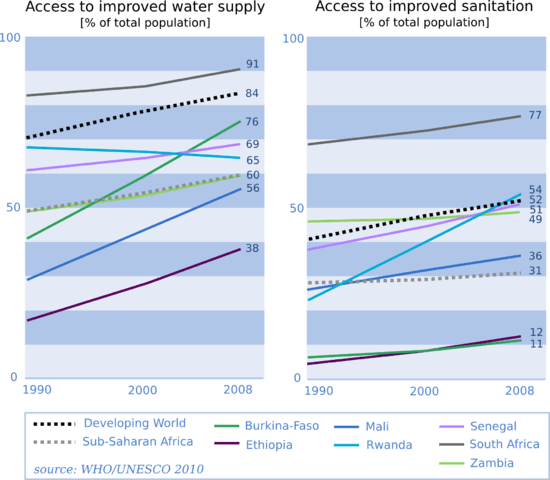

In Sub-Saharan Africa access to water supply and sanitation has improved, but the region lags behind all other developing regions: access to safe drinking water had increased from 49% in 1990 to 60% in 2008, while in the same time span access to improved sanitation had only risen from 28% to 31%. Sub-Saharan Africa did not meet the Millennium Development Goals of halving the share of the population without access to safe drinking water and sanitation between 1990 and 2015.[2] These trends in water supply and sanitation are directly reflected in health: the under-five child mortality had significantly decreased worldwide, but Sub-Saharan Africa showed the slowest pace of progress.[4] The new targets set under the Sustainable Development Goals will, unlike the MDGs have drinking water and sanitation reported seperatly i.e targets for access to safe and affordable drinking water (target 6.1) and adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene (target 6.2).[3] The SDGs have also included reporting on hygiene, that was missing within the MDGs.

National differences

There are large disparities amongst countries in the Sub-Saharan region. Access to safe drinking water varies from 38% in Ethiopia to 91% in South Africa, while the access to improved sanitation fluctuates from 11% in Burkina Faso to 77% in South Africa. The situation in Ivory Coast is significantly better, with the access to improved drinking water source at 82%[5]

The urban-rural disparities

In the entire Sub-Saharan region, water supply and sanitation coverage in urban areas is almost double the coverage in rural areas, both for water (83% in urban areas, 47% in rural areas) as for sanitation (44% vs. 24%). Yet, the rural areas improve at fast pace, whereas in urban areas the extension of water supply and sanitation infrastructure can barely keep up with the fast urban demographic growth.[2]

Different interpretations of access

Remark that the concepts 'access' and 'improved' are not unequivocal. The definitions used by the WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Program for Water Supply and Sanitation do not necessarily coincide with those of other surveys or national policies. The government of Burkina Faso, for instance, takes into account aspects such as waiting time and water quality. In fact, almost half of the Sub-Saharan households that according to WHO/UNICEF 'have access to improved water supply', spend more than half an hour a day collecting the water.[2] Although this loss of time is mentioned in the WHO/UNICEF report, it does not affect their 'improved' vs. 'non-improved' distinction.

National stakeholders in water supply and sanitation

Since the 1990s almost all African countries have been decentralising their political powers from the centre towards local authorities: in Mali it started in 1993, in Ethiopia in 1995, in Rwanda in 2002, in Burkina Faso in 2004, ... Along with the decentralisation process, a reform of the water supply and sanitation sector has been put through. The institutional structures for water supply and sanitation that came out of it differ throughout the continent. Two general distinctions can be made.

A first distinction should be made between water supply and sanitation responsibilities in (i) urban areas and (ii) rural areas. Most governments have created corporatised utilities for water supply and sanitation in the urban areas. In rural areas the responsibilities usually rest in the hands of the municipality, community-based groups, or local private companies. The task of the central government is generally limited to setting the national goals and regulations for water supply and sanitation.

A second distinction, with respect to the urban areas, exists between those countries (mostly francophone) that have retained one national utility active in all urban areas of the country, and other countries (mostly anglophone) that have further decentralised the utilities to local jurisdictions[6]

Urban areas

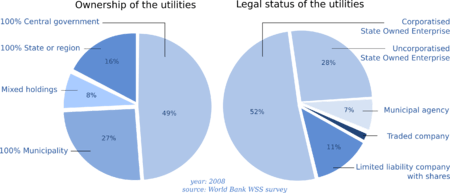

In the last two decades, the management of urban water supply and sanitation has been increasingly put in hands of newly created utilities. In some cases these water supply and sanitation utilities also supply electricity. The majority of these utilities are corporatized, meaning that they emulate a private company in terms of productivity and financial independence. Nevertheless, they widely differ in legal status and ownership structure.

There were hopes that, by creating independent utilities, their business could become commercially sustainable and attract private capital. Almost half of the Sub-Saharan countries have experimented with some form of private sector participation in the utility sector since the early 1990s, which was largely supported by the World Bank. The experience with these private sector contracts has been mixed. While they did not succeed in attracting much private capital, some of them improved performance. However, almost one third have been ended before their intended termination, such as in Dar es-Salaam in Tanzania. Others were not renewed.[6][7]

Today nearly half of the utilities are public enterprises and majority-owned by the central government.[6] Senegal is an example where private involvement was successful: the affermage (leasing) of the network to a private operator has considerably increased efficiency and contributed to increase access. Besides Senegal, private operators still have a role in South Africa (four utilities), Cameroon, Cape Verde, Ivory Coast, Gabon, Ghana, Mozambique, Niger and Uganda (in small towns).[7] In Uganda and Burkina Faso public national utilities were strengthened through short-term public-private partnerships in the form of performance-based service contracts.

The utilities never reach all households in their territory. The share of unconnected urban households fluctuates from over 80% in poor countries like Uganda, Mozambique, Rwanda, Nigeria, and Madagascar, to 21% in Namibia and 12% in South Africa.

Some African utilities are in charge of water supply only, while others are in charge of sanitation as well. Some national water utilities, especially in Francophone Africa, also provide electricity. This is the case in Gabon, Mauritania and Rwanda, among others.

Since fast demographic growth reveals itself in expanding peri-urban areas and slum areas - rarely served by water networks or sewers – the share of the urban households connected to piped water has been steadily decreasing from 50% in 1990 to 39% in 2005.[6] The unconnected households need to rely on alternatives –formal or informal– such as: shared standpipes or boreholes, water tankers and household resellers. Usually, standpipes are the main source of water for unconnected urban households.

Rural areas

The responsibility for water supply and sanitation in rural areas has in most countries been decentralised to the municipalities: they determine the water and sanitation needs and plan the infrastructure, in line with the national water laws. Various central governments have created a national social fund (supported by donors) from which the municipalities can draw money to finance rural water supply and sanitation infrastructure. Although the municipalities usually own the infrastructure, they rarely provide the service. This it is rather delegated to community-led organisations or local private companies. Studies by the World Bank and others suggest the need for more attention to private sector operation of all types of rural water supplies.[8]

In Kenya, Tanzania and South Africa, utilities provide services to rural dwellers as well, although this does not preclude the coexistence of different arrangements for the rural space in those countries.[6] In Rwanda local private operators are common in rural areas. Most countries in the region take on an active role in building infrastructure (mostly boreholes). Other countries are trying different approaches, such as self-supply of water and sanitation, where most of the investment costs for simple systems are born by the users.[9] Self-supply is currently part of National Policies in Ethiopia and has been implemented at scale in Zimbabwe in the past.[10]

Quality of service

A first indicator of the quality of water supply services is the continuity of service. The urban utilities deliver continuous services in Burkina Faso, Senegal and South Africa, but are highly intermittent in Ethiopia and Zambia. In rural areas, continuity is expressed by the ratio of water points out of order, or by the average time per year or per month that a water point is unusable. In low income Sub-Saharan countries, indicatively, over one third of the rural water supply infrastructure is in disuse.

A second indicator of quality is the compliance with microbiological water norms. WHO/UNESCO has recently developed a Rapid Assessment of Drinking-Water Quality (RADWQ) survey method. On average, in developing countries, compliance with the who norms is close to 90% for piped water, and between 40% and 70% for other improved sources.[2] No national or regional data have been published yet.

Financial aspects

Tariffs and cost recovery

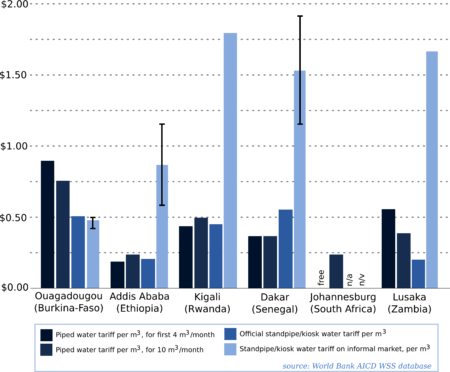

There is an overall underpricing of formal water and sanitation services in Sub-Saharan Africa.[7][11] A first consequence is an insufficient cost recovery, leading to dependency on foreign aid and governmental support, and to insufficient investments. Second, underpricing is socially unfair. Since the poorest social groups are less connected to water networks and sewerage, they need to turn to alternatives, and they pay in some cases a multiple of the formal tariff. Hence, the poorest are hit twice: they have less access to improved water supply and sanitation, and they need to pay more.

South Africa stands out for having introduced free basic utility services for all, including 6m3 of water per month for free.

Tariffs of about $0.40 per m3 are considered sufficient to cover operating costs in most developing-country contexts, while $1.00 would cover both operation, maintenance and infrastructure. Assuming that a tariff is affordable as long as the bill does not exceed 5% of the household’s budget, the World Bank calculates that even in the low-income Sub-Saharan countries up to 40% of the households should be able to pay the full-cost tariff of $1 per m3[12]

Efficiency

The number of employees per 1000 connections is an indicator of the technical efficiency of utilities. In Sub-Saharan Africa the average is 6.[13] The highest efficiency is observed in South Africa, where the four utilities need 2.1–4.0 employees per 1000 connections. Rwanda peaks with 38.6 employees per 1000 connections.[13]

Another indicator is the share of non-revenue water (water that is lost or not metered). In an efficiently managed system, this amount is below 25%. In 2005 it was estimated to be 20% in Senegal, 18% in Burkina Faso, 16% for the Water Utility Corporation in Botswana, 14% in Windhoek in Namibia and 12% in Drakenstein, South Africa. These utilities have achieved levels of non-revenue water similar to levels in OECD countries. However, in other African countries the level of non-revenue water is extremely high: For example, it exceeds 45% in Zambia, is more than 60% in Maputo (Water supply and sanitation in Mozambique|Mozambique), 75% in Lindi (Water supply and sanitation in Tanzania|Tanzania) and 80% in Kaduna (Nigeria).[14] Few data are available for efficiency in the rural space.

Expenditures

In Sub-Saharan Africa, current spending on water supply and sanitation (investments, operation and maintenance) totals to $7.6 billion per year, or 1.19% of the regional GDP. This includes $4.7 billion per year for investments (2001-2005 average). According to the World Bank, total expenditures are less than half of what would be required to achieve the Millennium Development Goals in Sub-Saharan Africa; that would need more than $ 16.5 billion per year or 2.6% of the regional GDP.[7] The African Development Bank estimates that $12 billion is required annually to cover Africa’s needs in improved water supply and sanitation.[15]

Expenditures are often not well targeted. According to a World Bank study, there is a large gap in expenditures between rural and urban areas, in particular capital cities. Public expenditures go to where they are most easily spent rather than where they are most urgently needed. Sanitation receives only a small part of public expenditures: Low household demand for sanitation results in politicians not seeing sanitation as a vote winner, and therefore allocating scarce resources to sectors with higher perceived political rewards.[16]

Financing

Out of the $4.7 billion of investments in water supply and sanitation in Sub-Saharan Africa, 70% is financed internally and only 30% is financed externally (2001-2005 average). Most of the internal financing is household self-finance ($2.1bn), which is primarily for on-site sanitation such as pit latrines. Public sector financing ($1.2bn) is almost as high as external financing (US$1.4bn). The contribution of private commercial financing has been negligible at $10 million only.[17]

The share of external financing varies greatly. In the 2001-2005 period official development assistance financed 71% of investments in Benin, 68% in Tanzania, 63% in Kenya, 43% in the DR of Congo, 34% in South Africa, 13% in Nigeria and less than 1% in Côte d'Ivoire or Botswana.[18] According to another World Bank study of 5 countries, in the 2002-2008 period official development assistance financed on average 62% of public expenditures on water and sanitation. The share varied from 83% in Sierra Leone to 23% in the Republic of Congo.[19]

External cooperation

In 2008, $1.6 billion of foreign aid flowed into the water supply and sanitation sector in Sub-Saharan Africa, which is 4% of all development aid disbursed to Sub-Saharan Africa. This foreign aid covered 21% of all expenditures in water supply and sanitation in Sub-Saharan Africa, and was principally directed to investments in infrastructure. Operation and maintenance is financed by the national governments and consumer revenues.[7]

The largest donors to water supply and sanitation in Sub-Saharan Africa are the World Bank, the EU institutions, the African Development Fund, and bilateral assistance from Germany and the Netherlands. The United States, although they are the largest donor in Sub-Saharan Africa in absolute numbers, play a marginal role in the water supply and sanitation sector.

| Total aid to SSA, in M$ and % of total | Aid to SSA in WSS, in M$ and % of total | |

|---|---|---|

| World Bank (IDA) | 4 856 (12.3%) | 378 (24.1%) |

| EU institutions | 5 056 (12.8%) | 266 (16.6%) |

| African Development Fund | 1 780 (4.5%) | 193 (12.0%) |

| Germany | 2 906 (7.4%) | 171 (10.7%) |

| The Netherlands | 1 446 (3.7%) | 137 (8.5%) |

| United States | 6 875 (17.4%) | 13 (0.8%) |

| Total received by SSA | 39 451 (100%) | 1 603 (100%) |

Especially in the poorer countries the presence of many different donors and Western NGOs puts a strain on the coherence of national strategies, such as in Burkina Faso and Ethiopia. Foreign aid comes in at all levels: the central government, the national social funds, the utilities, the local authorities, local NGOs,... Although most foreign actors try to inscribe their aid in the existing national structures, their implementation approaches and technical solutions often differ.

Strategies for improvement

The final report on Africa's Infrastructure,[7] has the following recommendations for the water supply and sanitation sector:

- continue the institutional reforms: more efficient internal processes, increased autonomy of the utilities, better performance monitoring

- improve the efficacy of governmental expenditure

- experiment with different models to connect the unconnected, since investments in piped networks cannot keep pace with urban growth

- devise socially fair tariffs that nonetheless cover the real cost of water supply and sanitation

- improve the understanding of groundwater extraction in urban areas, since this is the fastest growing source of improved water supply.

See also

References

- United Nations (PDF). United Nations https://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/2015_MDG_Report/pdf/MDG%202015%20rev%20(July%201).pdf. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - WHO/UNESCO (2010). Progress on Sanitation and Drinking-water: 2010 Update. Geneva: WHO press.JMP 2010 Update

- Roche, Rachel; Bain, Robert; Cumming, Oliver (9 February 2017). "A long way to go – Estimates of combined water, sanitation and hygiene coverage for 25 sub-Saharan African countries". PLOS ONE. 12 (2): e0171783. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0171783. ISSN 1932-6203.

- UN-WATER (2009) The United Nations World Water Development Report 3: Water in a Changing World. Paris: UNESCO Publishing.WWR 2009

- "Improved water source (% of population with access)". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- Africa Infrastructure Country Diagnostic (AICD) (2008). Ebbing Water, Surging Deficits: Urban Water Supply in Sub-Saharan Africa. AICD Background Paper 12. Washington: World Bank. AICD Background Paper 12

- Africa Infrastructure Country Diagnostic (AICD) (2010). Africa’s Infrastructure: a Time for Transformation. Washington: World Bank. Flagship report

- The World Bank, November 2010 "Private Operators and Rural Water Supplies : A Desk Review of Experience". Retrieved 2011-10-24.

- Rural Water Supply Network. "Rural Water Supply Network Self-supply site". www.rural-water-supply.net/en/self-supply. Retrieved 2017-03-19.

- Olschewski, Andre (2016), Supported Self-supply – learning from 15 years of experiences (PDF), 7th RWSN Forum “Water for Everyone”, 7ème Forum RWSN « L’eau pour tous », 29 Nov - 02 Dec 2016, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire

- Africa Infrastructure Country Diagnostic (AICD) (2009). Provision of water to the poor in Africa. Experience with water standposts and the informal water sector. Working Paper 13. Washington: World Bank. AICD Working Paper 13

- Africa Infrastructure Country Diagnostic (AICD) (2008). Cost Recovery, Equity, and Efficiency in Water Tariffs: Evidence from African Utilities. AICD Working Paper 7. Washington: World Bank. AICD Working Paper 7

- World Bank WSS survey database.

- Sudeshnha Ghosh Banerjee and Elvira Morella:Africa's Water and Sanitation Infrastructure. Access, Affordability, and Alternatives, World Bank, 2011, Appendix 3, Table A3.2 Distribution Infrastructure, p. 332-334

- African Development Bank (2010). Financing Water & Sanitation Infrastructure for Economic Growth and Development. Technical Summary: Proceedings and Outcomes of the Sessions During the 2nd African Water Week, 9–11 November 2009, Johannesburg, South Africa. Tunis: African Development Bank. Technical summary

- Meike van Ginneken; Ulrik Netterstrom; Anthony Bennett (December 2011). "More, Better, or Different Spending? Trends in Public Expenditure Reviews for Water and Sanitation in Sub-Sahara Africa". World Bank. pp. xi–xii. Retrieved 30 March 2012.

- Sudeshnha Ghosh Banerjee and Elvira Morella:Africa's Water and Sanitation Infrastructure. Access, Affordability, and Alternatives, World Bank, 2011, p. 217-219

- Sudeshnha Ghosh Banerjee and Elvira Morella:Africa's Water and Sanitation Infrastructure. Access, Affordability, and Alternatives, World Bank, 2011, Appendix 6, calculated from Table A6.3 Existing Financial Flows to Water and Sanitation Sectors, p. 376-377

- Meike van Ginneken; Ulrik Netterstrom; Anthony Bennett (December 2011). "More, Better, or Different Spending? Trends in Public Expenditure Reviews for Water and Sanitation in Sub-Sahara Africa". World Bank. p. 14. Retrieved 30 March 2012.

External links

- The International Benchmarking Network for Water and Sanitation Utilities

- Africa Infrastructure Knowledge Program

- The World Bank on private water operations in rural communities The World Bank, November 2010, pgs. 4-6.