Jemez Pueblo, New Mexico

Jemez Pueblo (/ˈhɛmɛz/; Jemez: Walatowa, Navajo: Mąʼii Deeshgiizh) is a census-designated place (CDP) in Sandoval County, New Mexico, United States. The population was 1,788 at the 2010 census.[1] It is part of the Albuquerque Metropolitan Statistical Area.

Jemez Pueblo, New Mexico | |

|---|---|

| Motto(s): The Gateway of the Jemez World | |

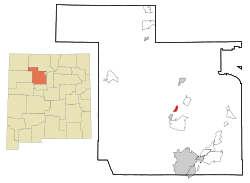

Location of Jemez Pueblo, New Mexico | |

Jemez Pueblo Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 35°36′38″N 106°43′39″W | |

| Country | United States |

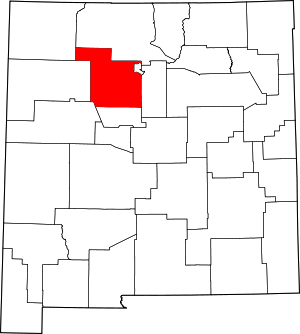

| State | New Mexico |

| County | Sandoval |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2.0 sq mi (5.3 km2) |

| • Land | 2.0 sq mi (5.3 km2) |

| • Water | 0.0 sq mi (0.0 km2) |

| Elevation | 5,604 ft (1,708 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 1,788 |

| • Density | 890/sq mi (340/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-7 (Mountain (MST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-6 (MDT) |

| ZIP code | 87024 |

| Area code(s) | 575 |

| FIPS code | 35-35250 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0928742 |

Jemez Pueblo | |

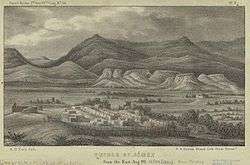

Jemez Pueblo, 1850 illustration | |

| |

| Nearest city | Bernalillo, New Mexico |

| Area | 124 acres (50 ha) |

| Built | 1700 |

| Architectural style | Late Victorian, Pueblo |

| NRHP reference No. | 77000926[2] |

| NMSRCP No. | 235 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | May 2, 1977 |

| Designated NMSRCP | February 1, 1972 |

The CDP is named after the pueblo at its center. Among Pueblo members, it is known as Walatowa.[3]

Geography

Jemez Pueblo is located at 33°36′39″N 106°44′39″W (35.610435, -106.727509).[4]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the CDP has a total area of 2 square miles (5.2 km2), all land.[1]

Demographics

It seems that a significant part of the Jemez Pueblo population originates from the surviving remnant of the Pecos Pueblo population who fled to Jemez Pueblo in 1838.

The Jemez speak a Kiowa–Tanoan language also known as Jemez or Towa.

As of the census[5] of 2000, there were 1,953 people, 467 households, and 415 families residing in the CDP. The population density was 957.0 people per square mile (369.6/km2). There were 499 housing units at an average density of 244.5 per square mile (94.4/km2). The racial makeup of the CDP was 0.41% White, 99.13% Native American, 0.31% from other races, and 0.15% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.95% of the population.

There were 467 households, out of which 39.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 39.2% were married couples living together, 35.1% had a female householder with no husband present, and 11.1% were non-families. 9.9% of all households were made up of individuals, and 2.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 4.18 and the average family size was 4.45.

In the CDP, the population was spread out, with 35.0% under the age of 18, 11.1% from 18 to 24, 28.8% from 25 to 44, 18.4% from 45 to 64, and 6.7% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 28 years. For every 100 females, there were 94.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 86.9 males.

The median income for a household in the CDP was $28,889, and the median income for a family was $30,880. Males had a median income of $20,964 versus $17,262 for females. The per capita income for the CDP was $8,045. About 27.2% of families and 25.5% of the population were below the poverty line, including 27.1% of those under age 18 and 34.6% of those age 65 or over.

Jemez runners

As much as 70% of the 1,890 Jemez people were living on their reservation lands in the early 1970s. Though by then an increasing number were switching to wage-earning work rather than agriculture, the residents continued to raise chile peppers, corn, and wheat, to speak their native language, and to maintain customary practices.

Running, an old Jemez pastime and ceremonial activity, grew even more popular than it had been before World War II. Prior to the advent of television at Jemez, tales of running feats had been a major form of entertainment on winter nights. Races continued to hold their ceremonial place as the years passed, their purpose being to assist the movement of the sun and moon or to hasten the growth of crops, for example. At the same time, they became a popular secular sport. The year 1959 saw the first annual Jemez All-Indian Track and Field Meet, won by runners from Jemez seven times in the first ten years. A Jemez runner, Steve Gachupin, won the Pikes Peak Marathon six times, setting a record in 1968 by reaching the top in just 2 hours, 14 minutes, 56 seconds.[6]

Notable Jemez people

- Cliff Fragua, Jemez sculptor[7]

- Mary Ellen Toya, (1934–1990), artist[8]

- Evelyn M. Vigil, artist[9]

See also

- Pueblo People

- Jemez Historic Site- Formerly Jemez State Monument

- Jemez Springs, New Mexico

- Pueblo Revolt

- Jemez River

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Sandoval County, New Mexico

References

- "2010 Census Gazetteer Files - Places: New Mexico". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved October 20, 2017.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- "The Pueblo of Jemez". Department of Resource Protection. 2008-04-14. Archived from the original on 2007-09-29.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- Sando, Joe S., Nee Hemish: A History of Jemez Pueblo, Clear Light Publishing, Santa Fe, New Mexico, 2008 p. 169

- "Cliff Fragua". Indigenous Sculptors Society. Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- 1953-, Schaaf, Gregory (2002). Southern Pueblo pottery : 2000 artist biographies, c. 1800-present : with value/price guide featuring over 20 years of auction records. Schaaf, Angie Yan. (1st ed.). Santa Fe, N.M.: CIAC Press. ISBN 978-0966694857. OCLC 48624322.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Hayes, Allan; Blom, John; Hayes, Carol (2015-08-03). Southwestern Pottery: Anasazi to Zuni. Taylor Trade Publishing. ISBN 9781589798625.

Further reading

- Sando, Joe S., Nee Hemish: A History of Jemez Pueblo, Clear Light Publishing (2008), trade paperback, 264 pages, ISBN 1-57416-091-5

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jemez Pueblo. |