Further Austria

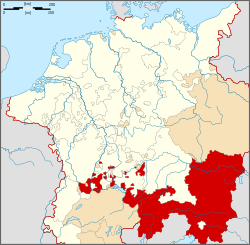

Further Austria, Outer Austria or Anterior Austria (German: Vorderösterreich, formerly die Vorlande (pl.)) was the collective name for the early (and later) possessions of the House of Habsburg in the former Swabian stem duchy of south-western Germany, including territories in the Alsace region west of the Rhine and in Vorarlberg.

| Vorderösterreich Österreichische Vorlande | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Territory of Habsburg Monarchy and the Austrian Empire | |||||||||||||||||

| 1278–1805 | |||||||||||||||||

Coat of arms

| |||||||||||||||||

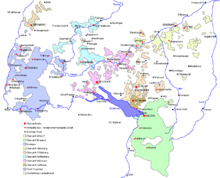

Further Austrian territories, after the loss of the Sundgau in 1648 | |||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Ensisheim Freiburg im Breisgau | ||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages Napoleonic Wars | ||||||||||||||||

• Established | 1278 | ||||||||||||||||

| 1805 | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||||

While the territories of Further Austria west of the Rhine and south of Lake Constance (except Konstanz itself) were gradually lost to France and the Swiss Confederacy, those in Swabia and Vorarlberg remained under Habsburg control until the Napoleonic Era.

Geography

Further Austria mainly comprised the Alsatian County of Ferrette in the Sundgau, including the town of Belfort, and the adjacent Breisgau region east of the Rhine, including Freiburg im Breisgau after 1368. Also ruled from the Habsburg residence in Ensisheim near Mühlhausen were numerous scattered territories stretching from Upper Swabia to the Allgäu region in the east, the largest being the margravate of Burgau between the cities of Augsburg and Ulm. During the Habsburg Monarchy they were humorously called "tail feathers of the Imperial Eagle". Some estates in Vorarlberg possessed by the Habsburgs were also considered part of Further Austria, though they were temporarily directly administered from Tyrol.

History

The original home territories of the Habsburgs, the Aargau with Habsburg Castle and much of the other original possessions south of the High Rhine and Lake Constance were already lost in the 14th century to the expanding Swiss Confederacy after the battles of Morgarten (1315) and Sempach (1386). These territories were never considered part of Further Austria – except for the Fricktal region around Rheinfelden and Laufenburg, which remained a Habsburg possession until 1797.

From 1406 until 1490 Further Austria together with the Habsburg County of Tyrol was included in the definition of "Upper Austria" (Oberösterreich, not to be confused with the modern Austrian state of Upper Austria). From 1469 to 1474 Archduke Sigismund gave large parts in pawn to the Burgundian duke Charles the Bold.

At the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648, the Sundgau became part of France. After the Ottoman wars many inhabitants of Further Austria were encouraged to emigrate and settle in the newly acquired Transylvania region, people that later were referred as Danube Swabians. In the 18th century, the Habsburgs acquired a few minor new Swabian territories, such as Tettnang in 1780.

In the reorganization of the Holy Roman Empire in the course of the French Revolutionary Wars, much of Further Austria, including the Breisgau, was by the 1801 Treaty of Lunéville granted as compensation to Ercole III d'Este, former duke of Modena and Reggio, who however died two years later. His heir as his son-in-law was Archduke Ferdinand of Austria-Este, the uncle of Emperor Francis II.

After the Austrian defeat at the Battle of Austerlitz and the Peace of Pressburg in 1805, Further Austria was entirely dissolved and the former Habsburg territories were assigned to the Grand Duchy of Baden (Breisgau), the Kingdom of Württemberg (Rottenburg and Horb) and the Kingdom of Bavaria (Weitnau Günzburg, Weißenhorn), as rewards for their alliance with Napoleonic France. Minor estates passed to Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen and the Grand Duchy of Hesse. Fricktal had already become a French protectorate in 1799 and part of the Helvetic Republic in 1802, incorporated into the Swiss canton of Aargau the next year.

After the defeat of Napoleon, there was some discussion at the Congress of Vienna of returning part of all of the Vorlande to Austria, but in the end only Vorarlberg returned to Austrian control, as Foreign Minister Klemens von Metternich did not want to offend the rulers of the South German states and hoped that removing Austria from its advanced position on the Rhine would reduce tensions with France.

Administrative division

As of 1790 Further Austria was subdivided into ten districts (Oberämter):

- Breisgau (with Fricktal) at Freiburg

- Offenburg: several localities in the present Ortenaukreis, the Imperial city of Offenburg not included

- Hohenberg, present Ostalbkreis, former county, at Rottenburg am Neckar

- Nellenburg, former landgraviate, at Stockach

- Altdorf (former Vogtei Swabia), today Weingarten

- Tettnang, former County of Montfort

- Günzburg, former Margraviate of Burgau

- Winnweiler in the Palatinate, former County of Falkenstein

- the former Imperial city of Konstanz

- Bregenz, present-day Vorarlberg, then administrated from Tyrol.

Habsburg rulers

Politically, the Further Austrian territories were held by the Habsburg (Arch-)Dukes of Austria from 1278 onwards. Upon the 1379 Treaty of Neuberg, they together with Carinthia, Styria, Carniola and Tyrol fell to the Leopoldian line:

- Leopold III, until 1386

- William, son, 1386–1406

Further divided into Inner Austria proper (Styria, Carinthia and Carniola) and Upper Austria (Tyrol and Further Austria), ruled by:

- Frederick IV, younger brother of William, 1406-1439 (regent in Further Austria since 1402)

- Frederick V, nephew of William, ruler of Inner Austria, 1439-1446 (regent)

- Sigismund, son of Frederick IV, 1446–1490

In 1490 all Habsburg possessions were re-unified under the rule of Frederick V, Holy Roman Emperor since 1452. Upon the death of Emperor Ferdinand I of Habsburg in 1564, Further Austria and Tyrol was inherited by his second son:

- Ferdinand II, 1564–1595

- Matthias, 1595–1619, nephew, Holy Roman Emperor from 1612, with his younger brother

- Maximilian III as regent, 1612–1618

In 1619 the Habsburg hereditary lands were re-unified under the rule of Emperor Ferdinand II. He gave Further Austria to his younger brother:

- Leopold V, 1623–1632

- Ferdinand Charles, son, 1632–1662

- under the tutelage of his mother Claudia de' Medici, 1632–1646

- Sigismund Francis, brother 1662-1665

In 1665 the Habsburg lands were finally re-unified under the rule of Emperor Leopold I.

Literature

- Becker, Irmgard Christa, ed. Vorderösterreich, Nur die Schwanzfeder des Kaiseradlers? Die Habsburger im deutschen Südwesten. Süddeutsche Verlagsgesellschaft. Ulm 1999, ISBN 3-88294-277-0 (Katalog der Landesausstellung).

- Döbeli, Christoph. Die Habsburger zwischen Rhein und Donau. 2. Auflage, Erziehungsdepartement des Kantons Aargau, Aarau 1996, ISBN 3-9520690-1-9.

- Maier, Hans and Volker Press, eds. Vorderösterreich in der frühen Neuzeit. Thorbecke, Sigmaringen 1989, ISBN 3-7995-7058-6.

- Metz, Friedrich, ed. Vorderösterreich. Eine geschichtliche Landeskunde. 4. überarbeitete und erweiterte Auflage. Rombach, Freiburg i. Br. 2000, ISBN 3-7930-9237-2.

- Rommel, Klaus, ed. Das große goldene Medaillon von 1716. (Donativ des Breisgaus, Schwäbisch-Österreich und Vorarlberg zur Geburt Leopolds). Rommel: Lingen 1996, ISBN 3-9807091-0-8.

- Zekorn, Andreas, Bernhard Rüth, Hans-Joachim Schuster and Edwin Ernst Weber, eds. Vorderösterreich an oberem Neckar und oberer Donau. UVK Verlagsges., Konstanz 2002, ISBN 3-89669-966-0 (hrsg. im Auftrag der Landkreise Rottweil, Sigmaringen, Tuttlingen und Zollernalbkreis).

.svg.png)