Villa Barbaro

Villa Barbaro, also known as the Villa di Maser, is a large villa at Maser in the Veneto region of northern Italy. It was designed and built by the Italian Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio, with frescos by Paolo Veronese and sculptures by Alessandro Vittoria, for Daniele Barbaro, Patriarch of Aquileia and ambassador to Queen Elizabeth I of England and his brother Marcantonio, an ambassador to King Charles IX of France. The villa was added to the list of World Heritage Sites by UNESCO in 1996.

| Villa Barbaro | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Palladian |

| Town or city | Maser, Veneto |

| Country | Italy |

| Construction started | c.1560 |

| Client | Barbaro family |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Andrea Palladio |

| Website | |

| www | |

| Part of | City of Vicenza and the Palladian Villas of the Veneto |

| Criteria | Cultural: (i), (ii) |

| Reference | 712bis-018 |

| Inscription | 1994 (18th session) |

| Extensions | 1996 |

| Area | 6.57 ha (16.2 acres) |

| Coordinates | 45.8122°N 11.9764°E |

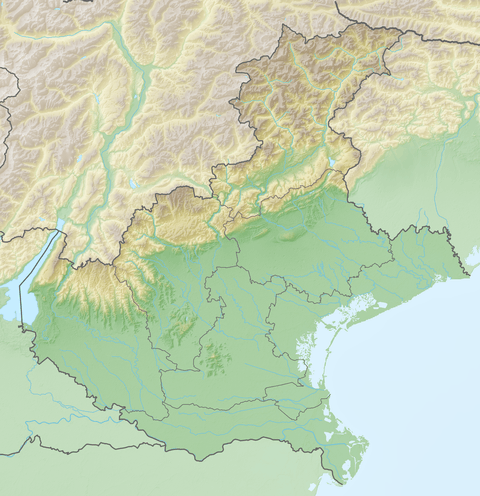

Location of Villa Barbaro in Veneto  Villa Barbaro (Italy) | |

History

The land originally belonged to the Arbil and then the Giustiniani families, before becoming property of the Barbaro family. Authorities vary as to the dates given for the building of the villa. The architectural historian Adalbert dal Lago states it was built between 1560 and 1570,[1] while others state that the villa was mostly completed by 1558.[2] Hobson[3] concurs with dal Lago that the date of commencement was probably 1560. By this date Palladio had provided the illustrations for one of Daniele's publications, a commentary on the writings of the Roman architect Vitruvius. Hobson credits Daniele with the idea of not only building the villa but also the choice of architect and the sculptor Alessandro Vittoria. While Daniele was better-known as a connoisseur of the arts, it was for the use of Marcantonio's family and descendants that the villa was intended in the long term.[4]

After the Barbaro family died out, the villa passed through the female line into the ownership of the Trevisan and then the Basadonna families, followed by the Manin. Ludovico Manin, Venice's last doge, sold it to Gian Battista Colferai who had rented for some years.

Having been allowed to become ruinous, the villa was purchased in 1850 by the wealthy industrialist Sante Giacomelli who began to renovate it, making use of the work of artists like Zanotti and Eugene Moretti Larese. During the Great War, the villa was used as a headquarters by General Squillaci of the Italian Third Army.

In 1934, Count Giuseppe Volpi di Misurata, founder of the Venice Film Festival and father of Giovanni Volpi, acquired the villa for his daughter Marina, who continued the restoration. Marina's descendants still live there today.

In 1996, UNESCO designated Villa Barbaro as part of the World Heritage Site "City of Vicenza and the Palladian Villas of the Veneto", which includes more than twenty villas. It is open to the public.[5] The complex is also home to a farm that produces wine named after the villa.

Architecture

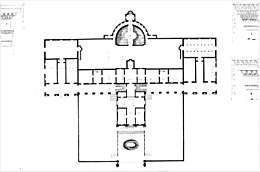

Palladio planned the villa on low lines extending into a large park. The ground floor plan is complex: rectangular with perpendicular rooms on a long axis, the central block projects and contains the principal reception room. The central block, which is designed to resemble the portico of a Roman temple, is decorated by four Ionic columns, a motif which takes its inspiration from the Temple of Fortuna Virilis in Rome. The central block is surmounted by a large pediment with heraldic symbols of the Barbaro family in relief.[6] Below the pediment is a Latin inscription on the entablature dedicating the villa to the brothers' father; the inscription translates, "Daniel Barbaro, Patriarch of Aquileia, and Marcantonio his brother, sons of Francesco Barbaro".[7]

The central block is flanked by two symmetrical wings. The wings have two floors but are fronted by an open arcade. Usually Palladio designed the wings to provide functional accommodation for agricultural use. The Villa Barbaro is unusual in having private living quarters on the upper level of the barchesse(that is, the rooms behind the arcades of the two wings). The Maser estate was a fairly small one and would not have needed as much storage space as was built at Villa Emo, for example.

The wings are terminated by pavilions which feature large sundials set beneath their pediments. The pavilions were intended to house dovecotes on the uppermost floor, while the rooms below were for wine-making, stables and domestic use. In many of Palladio's villas similar pavilions were little more than mundane farm buildings behind a concealing facade. A typical feature of Palladio's villa architecture, they were to be much copied and changed in the Palladian architecture inspired by Palladio's original designs.

Interior

The interior of the piano nobile is painted with frescoes by Paolo Veronese in the artist's most contemporary style of the period. These paintings constitute the most important fresco cycle by this artist and were inspirational to many of the frescoes painted by other villa artists at that time. The frescoes have been dated to the beginning of the 1560s, or slightly before. To describe the frescoes by room: in the Hall of Olympus, Veronese painted Giustiniana, mistress of the house and wife of Marcantonio Barbaro, with her youngest son, wetnurse and the family pets, a parrot and spaniel dog. The family dog also appears in another room, The Room of the Little Dog. The Crociera room depicts imaginary landscapes and the villa's staff peering around trompe-l'œil doors. The Room of the Oil Lamp has images symbolizing virtuous behavior and strength. The Bacchus Room shows winemaking scenes and a chimneypiece carved with the figure of Ambundance, reflecting the bucolic ideals and splendor of the villa.[8] The ceiling fresco of the north salon is a depiction of the planets represented by classical deities, which are linked to the signs of the zodiac. Gaia, the Earth goddess, is apparently depicted astride a dragon.[9]

Church (Tempietto Barbaro)

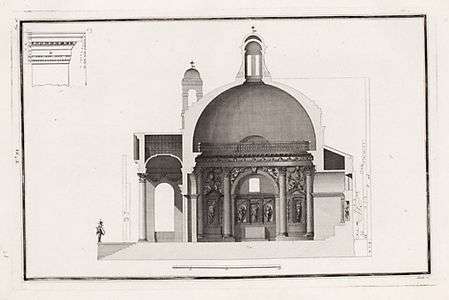

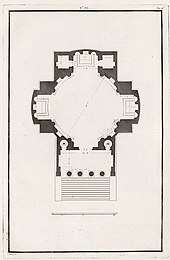

Towards the end of his life, Palladio received the opportunity to build a church, the Tempietto Barbaro, to serve the Villa Barbaro and the village of Maser. It is not certain when Tempietto Barbaro was built, but an inscription on the frieze dated 1580 gives the names of both Palladio and his patron Marcantonio Barbaro. The Tempietto and the Teatro Olimpico were Palladio's last works and tradition says that he died at Maser while working on the building.

At Maser, the patron and the architect agreed on a centralised building closely following classical models. In some other church commissions such as the Redentore (which is a related design to the Tempietto), Palladio had been obliged to go against his inclinations and provide a long nave, but at Maser he had a patron who preferred a centralised plan. The connection of a temple front to a domed building refers to the Pantheon. A portico that is drawn out a long way, and has unusually steep proportions, leads along with the diagonal parts of the pediment to two small bell towers, which for their part pass on the upward-moving trend to the dome. The five spaces between the columns are framed by pillars, which are like the middle four columns in their entasis and tapering. The facade probably faced on to a small square originally.

The interior has stucco decorations attributed to Alessandro Vittoria. An entablature is finished with a rich decoration of cherubs and tendrils and creates a transition to the dome vault, along with a balustrade. Palladio alternates deep niches on a rectangular ground-plan and closed wall areas with figure tabernacles between the eight regular half-columns. The lower part of the building is completed by an unbroken continuous ledge, whose profile – three flat bands which are contrasted with each other by ovolo moulding – is taken over from the arcade arches. The architect contrasts two forms of cylinder and semi-sphere by a repeated emphasis on horizontals, and, over and above that, divides them into a palpable terrestrial zone and into a light, celestial one that cannot be precisely gauged with the eye.

Nymphaeum

Normally Palladio did not involve himself in the details of garden design. However, at Maser there is a classical garden feature, a nymphaeum. This arching architectural structure frames a natural spring, and may be influenced by a nymphaeum at Villa Giulia.

It has seven figural statues in niches and four nearly free-standing figures which may have been carved by Marcantonio Barbaro himself. The spring forms a pool, which can be used for fishing. The water also flowed to the kitchen as well as watered the gardens.[10]

In the media

In the 1990s the villa was featured in a production by the American TV presenter Bob Vila for A&E Network (Guide to Historic Homes: In Search of Palladio).[11] More recently the villa has attracted the attention of the British TV presenter Dan Cruickshank who featured the building in a BBC series (Dan Cruickshank's Adventures in Architecture). It also appeared in Episode 3, "Picturing Paradise", of the BBC series Civilisations, presented by Simon Schama and first broadcast in 2018.[12]

See also

References

- Dal Lago, Adalbert. Villas and Palaces of Europe, p.50, Paul Hamlyn 1969.

- Villa Barbaro: Architecture, Knowledge and Arcadia, ANU (Australian National University) 2003 retrieved 9 July 2007

- Hobson, op. cit.

- Hobson, ibid.

- Villa di Maser website, 2008 Archived 13 April 2006 at the Wayback Machine (in English and Italian) Accessed 2008-06-09, when the site advised of special opening hours for the "Palladio 500" quincentenary

- Wundram, Manfred, "Andrea Palladio 1508-1580, Architect between the Renaissance and the Baroque" Taschen, Köln, ISBN 3-8228-0271-9 p.123

- Rybczynski, Witold, "The Perfect House",

- Boulton, Susie & Catling, Christopher, "Villas of Palladio: Villa Barbaro" in Venice & the Veneto, Dorling Kindersley, London 2001 p.25 ISBN 1-56458-861-0

- Italian Palladian Villa at Maser - Website belonging to Paul E. Field Archived 7 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine accessed 2008-06-09

- Wundram, Manfred, op. cit. pp. 123/128

- BobVila.com. "Bob Vila's Guide to Historic Homes: In Search of Palladio".

- Moretti, Laura (23 March 2018). "How the Barbaro brothers created the perfect Renaissance villa". British Academy. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

Literature

- Hobson, Anthony wrote the material on Villa Barbaro (pp 89–97) in Great Houses of Europe, edited by Sitwell, Sacheverell, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London 1964. ISBN 0-600-33843-6.

- Fischer, Sören: „Denn ein üppiger Rebstock strebt über das ganze Gebäude hin zum First und erklettert ihn“ - Paolo Veronese, Andrea Palladio und die Stanza di Bacco in der Villa Barbaro als Pavillon Plinius‘ des Jüngeren. in: Kunstgeschichte. Open Peer Reviewed Journal, 2013, PDF

- Fischer, Sören: Das Landschaftsbild als gerahmter Ausblick in den venezianischen Villen des 16. Jahrhunderts - Sustris, Padovano, Veronese, Palladio und die illusionistische Landschaftsmalerei, Petersberg 2014, pp. 110–127. ISBN 978-3-86568-847-7

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Villa Barbaro. |

- Official website

- (IT, EN) Details on Villa Barbaro with bibliography of CISA - International Center for Studies of architecture Andrea Palladio (source for the description of the project)

- Travel with a Curator