Comtat Venaissin

The Comtat Venaissin (Provençal: lou Coumtat Venessin, Mistralian norm: la Coumtat, classical norm: lo Comtat Venaicin; 'County of Venaissin'), often called the Comtat for short, was a part of the Papal States (1274‒1791) in what is now the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of France.

Comtat Venaissin | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1274–1791 | |||||||||||

Flag

Coat of arms

| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Status | Papal enclave | ||||||||||

| Capital | Venasque (1274-1320) Carpentras (1320–1791) | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Provençal | ||||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||||

• Death of Alphonse, Count of Poitiers | 21 August 1271 | ||||||||||

• Acquired by Papacy | 1274 | ||||||||||

| 1320 | |||||||||||

| 1348 | |||||||||||

• French occupation | 1663, 1668, 1768–74 | ||||||||||

| 14 September 1791 | |||||||||||

| Currency | Roman scudo | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||

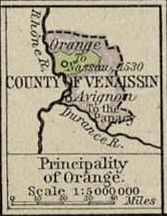

The entire region was an enclave within the Kingdom of France, comprising the area around the city of Avignon (itself always a separate comtat) roughly between the Rhône, the Durance and Mont Ventoux, and a small exclave located to the north around the town of Valréas bought by Pope John XXII. The Comtat also bordered (and mostly surrounded) the Principality of Orange. The region is still known informally as the Comtat Venaissin, although this no longer has any political meaning.

History

In 1096, the Comtat was part of the Margraviate of Provence that was inherited by Raymond IV, Count of Toulouse from William Bertrand of Provence. These lands in the Holy Roman Empire belonged to Joan, Countess of Toulouse, and her husband, Alphonse, Count of Poitiers.[1] Alphonse bequeathed it to the Holy See on his death in 1271. Since this happened during an interregnum, there was no Holy Roman Emperor to protect Joan's rights.

The Comtat became a Papal territory in 1274. The region was named after its former capital, Venasque, which was replaced as capital by Carpentras in 1320.

Avignon was sold to the papacy by Joanna I, Queen of Naples and Countess of Provence, in 1348,[2] whereupon the two comtats were joined together to form a unified papal enclave geographically, though retaining their separate political identities.

The enclave's inhabitants did not pay taxes and were not subject to military service, making life in the Comtat considerably more attractive than under the French Crown. It became a haven for French Jews, who received better treatment under papal rule than in the rest of France. The Carpentras synagogue, built in the 14th century, is the oldest in France, and until the French Revolution preserved a distinctive Provençal Jewish tradition.

Successive French rulers sought to annex the region to France. It was invaded by French troops in 1663, 1668 and 1768–1774 during disputes between the Crown and the Church. It was also subjected to trade and customs restrictions during the reigns of Louis XIV and Louis XV.

Papal control continued until 1791, when an unauthorized plebiscite, under pressure from French revolutionaries, was held and the inhabitants voted for annexation by France. A few years later, Vaucluse département was created based on Comtat Venaissin including the exclave of Valréas and a part of the Luberon for the southern half. The papacy did not recognise this formally until 1814.

Administration

Under the Counts of Toulouse, the chief officer of the Comtat Venaissin was the Seneschal.[3]

From 1294 to 1791 the chief administrator of the Comtat Venaissin was the Rector, who was appointed directly by the Pope. Most of the incumbents were in fact prelates, either Archbishops or Bishops, and the Rector therefore had the right to wear a purple garb, similar to that of an Apostolic Chamberlain.[4] His official residence was in Carpentras. He had no authority over Avignon, however, which was administered by a Cardinal Legate or a Vice-Legate, also appointed directly by the Pope.[5] Gradually, however, the power of the Vice-Legate encroached on that of the Rector, until the Cardinal virtually held the position of a governor, and the Rector had the functions of a judge. In both cases their tenure was for a period of three years, renewable.[6]

The Rector had the right to receive the feudal oaths of homage of all the papal vassals. He also had the right to receive the oaths of bishops who held property by virtue of their office which was in feudal tenure from the pope. The Rector named the Notaries of the Comtat. He presided at the negotiation and payment of revenues of the Apostolic Chamber. His court was the Supreme Court of the Comtat Venaissin, and he had both criminal and civil jurisdiction of the first instance, and appellate jurisdiction from the courts of the regular judges of the three judicial circuits.[7]

The Rector was seconded by a Vice-Rector, named the Lieutenant of the Rector, also a papal appointee. He had judicial powers similar to those of the Rector.

The administration of the Comtat was in the hands of the Estates of the Comtat, which consisted of the Élu (a nobleman), the Bishop of Carpentras, the Bishop of Cavaillon, the Bishop of Vaison, and eighteen representatives of the three judicial districts into which the Comtat was divided. The Estates held their meetings at Carpentras.[8]

The Apostolic Camera (Treasury of the Holy Roman Church) had a permanent office in Carpentras, with full jurisdiction in all financial matters concerning the rights of the Holy See in the Comtat. This included the obligations of bishops and other ecclesiastical persons to the papacy.[9]

See also

References

- Madaule, Jacques. The Albigensian Crusade. New York, Fordham University Press, 1967.

- Diana Wood (2002). Clement VI: The Pontificate and Ideas of an Avignon Pope. Cambridge University Press. pp. 47–50. ISBN 978-0-521-89411-1.

- Expilly, p. 91.

- Expilly, p. 92 column 1.

- A list of the Legates and Vice-Legates can be found in: Denis de Sainte-Marthe (1715). Gallia christiana, in provincias ecclesiasticas distributa (in Latin). Tomus primus. Paris: Coignard. pp. 841–850., and Roger Vallentin Du Cheylard (1890). Notes sur la chronologie des vice-légats d'Avignon au XVIe siècle: extrait des Mémoires de l'Académie de Vaucluse (in French). Seguin frères. [Extrait des Mémoires de l'Académie de Vaucluse 9 (1890) 200–213].

- Séguin de Pazzis, p. 19.

- Expilly, pp. 91–92.

- Séguin de Pazzis, p. 32.

- Expilly, p. 92 column 2.

Bibliography

- André, J. F. (1847). Histoire du gouvernement des Recteurs pontificaux dans le Comtat-Venaissin: D'après les notes recueillies par Charles Cottier (in French). Carpentras: Devillario.

- Arnaud, Eugène (1884). Histoire des protestants de Provence, comtat Venaissin et de la principauté d'Orange (in French). Paris: Grassart. p. 140.

- Calmann, Marianne (1984). The carrière of Carpentras. Published for the Littman Library by Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-710037-0. [The Jewish community of the Comtat Venaissin]

- Charpenne, Pierre (1886). Histoire des réunions temporaires d'Avignon et du Comtat Venaissin à la France (in French). Paris: Calmann Lévy.

- Expilly, Jean-Joseph (1764). Dictionnaire géographique, historique et politique des Gaules et de la France (in French). Tome II. Amsterdam: Desaint et Saillant. [article 'Carpentras']

- Mouliérac-Lamoureux, Rose Leone (1977). Le Comtat Venaissin pontifical: 1229-1791 (in French). Vedene: Comptoir Général du Livre Occitan.

- Moulinas, René (1992). Les juifs du Pape: Avignon et le Comtat Venaissin (in French). Paris: Editions Albin Michel. ISBN 978-2-226-05866-9.

- Séguin de Pazzis, Maxime (1808). Mémoire statistique sur le département de Vaucluse (in French). Carpentras: Imprimerie de D.G. Quenin.

- Soullier, Charles (1844). Histoire de la révolution d'Avignon et du Comté-Venaissin, en 1789 & années suivantes (in French). Paris: Seguin aîné.