Uranium mining in Arizona

Uranium mining in Arizona has taken place since 1918. Prior to the uranium boom of the late 1940s, uranium in Arizona was a byproduct of vanadium mining of the mineral carnotite.

Carrizo Mountains

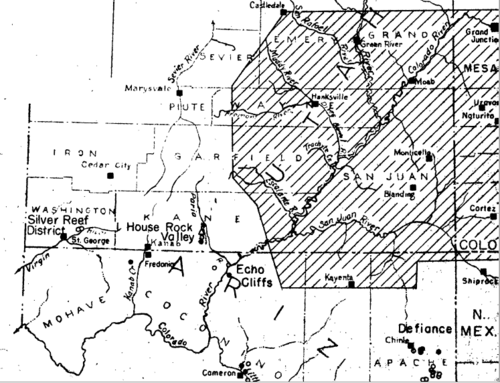

Uranium mining started in 1918 in the Carrizo Mountains as a byproduct of vanadium mining. The district is in Apache County, in the northeast corner of Arizona. The uranium and vanadium occur as carnotite in sandstone of the Salt Wash member of the Morrison Formation (Jurassic). Production stopped in 1921. Another period of mining took place from 1941 to 1966, producing 360,000 pounds (160 metric tons) of uranium oxide (U3O8).[1]

Monument Valley

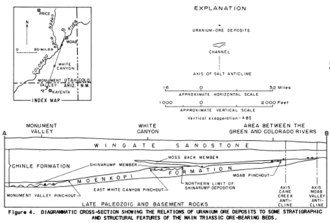

A Navajo discovered uranium in 1942 in Monument Valley on the Navajo Nation in northeast Arizona. The first mine in the district opened in 1948. Uranium and uranium-vanadium minerals occur in fluvial channels of the Shinarump Sandstone member of the Triassic Chinle Formation. Ore deposits are associated with carbonized wood in the sandstone.[2] Mining stopped in the Monument Valley district in 1969, after producing 8.7 million pounds (3900 metric tons) of uranium oxide, more than has been produced from any other uranium mining district in Arizona.[3] In 2005 the Navajo Nation declared a moratorium on uranium mining on the reservation, for environmental and health reasons.

Lukachukai Mountains

In 1948, a copper deposit in the Moenkopi Formation was discovered to have economic concentrations of uranium. The deposit was in the Lukachukai Mountains of Apache County. Uranium totaling 3.5 million pounds (1600 metric tons) of U3O8 was produced from 1950 until the mines closed in 1968.[1]

Cameron district

Navajo prospector Hosteen Nez found uranium near Cameron in Coconino County in 1950. The uranium is in the Kayenta Formation and the Chinle Formation. Production was from 1950 to 1963, and totaled 1.2 million pounds (540 metric tons) of U3O8.[1]

Collapse breccia pipes

Uranium was discovered in the Orphan copper mine near the south rim of the Grand Canyon in 1950. The mine has been private property since 1906, and is today completely surrounded by Grand Canyon National Park. The discovery led to the finding of uranium in other collapse breccia pipes in northern Arizona. The breccia pipes were formed when overlying rocks collapsed into caverns formed in the Mississippian Redwall Limestone. The pipes are typically 300 feet (91 m) in diameter, and may extend up to 3,000 feet (910 m) vertically.

Sierra Ancha district

Uranium mining started in 1953 from deposits in the Precambrian Dripping Spring Quartzite in Gila County. The uranium mineral is most commonly uraninite, which occurs with pyrite, marcasite, and chalcopyrite. The orebodies are in veins or strataform deposits within one-half mile of diabase intrusions.[4]

Date Creek Basin

The Anderson uranium deposit was discovered in 1955 by an airborne gamma-radiation survey. Small amounts of ore were produced from 1955 to 1959. Uranium is associated with organic material in carbonaceous Miocene siltstones and mudstones of lacustrine and paludal origin of the Chapin Wash formation of the Date Creek Basin in Yavapai, La Paz, and Mohave counties.[5] The Anderson mine is now owned by Concentric Energy Corp. which is doing extensive development work to bring it into production.[6]

Porphyry copper byproduct

For some years starting in 1980, the Twin Buttes copper mine in Pima County recovered uranium as a byproduct from leach solutions recovering copper from waste material.[7]

Uranium mining and native people

After the end of World War II, the United States encouraged uranium mining to build nuclear weapons stockpiles. Large uranium deposits were found on and near the Navajo Reservation, and mining companies hired many Navajos. Disregarding the health risks of radiation exposure, the private companies and the United States Atomic Energy Commission failed to inform the Navajo workers about the dangers and to regulate the mining to minimize contamination. As more data was collected, they were slow to take appropriate action for the workers.

Studies show that the Navajo mine workers and numerous families on the reservation have suffered high rates of disease from environmental contamination, but for decades, industry and the government failed to regulate or improve conditions, or inform workers of the dangers. As high rates of illness began to occur, workers were often unsuccessful in court cases seeking compensation, and the states at first did not officially recognize radon illness. In 1990 the US Congress passed the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act, to settle such cases and provide needed compensation.

In 2008 the US Congress authorized a five-year, multi-agency cleanup of uranium contamination on the Navajo Nation reservation; identification and treatment of contaminated water and structures has been the first priority. Certain water sources have been closed, and numerous contaminated buildings have been taken down. By the summer of 2011, EPA had nearly completed the first major project of removal of 20,000 cubic yards of contaminated earth from the Skyline Mine area.

Current activity

There are currently no producing uranium mines in Arizona. Denison Mines planned to begin mining its Arizona One mine in 2007.[8] The deposit is in a breccia pipe on the Colorado Plateau of northern Arizona.[9] In March 2011, the State of Arizona issued air and water permits to Denison which would allow uranium mining to resume at three locations north of the Grand Canyon, subject to federal approval.[10]

As of May 2015, Energy Fuels was preparing to mine uranium at its Canyon mine, a deposit on US Forest Service land, six miles from the south rim of the Grand Canyon. The deposit was discovered in the 1970s, and partially developed as an underground mine under a Forest Service permit in the late 1980s, but never put into production. The Canyon deposit holds enough ore to yield an estimated 1.63 million pounds of uranium concentrate U3O8. A coalition of groups, including the Havasupai Tribe, the Sierra Club, the Grand Canyon Trust, and the Center for Biological Diversity, sued the Forest Service to stop the reactivation of the mine. In April 2015 the US District Court for the District of Arizona ruled in favor of the Forest Service and Energy Fuels, and allowed work on the mine to proceed.[11] The plaintiffs plan to appeal.[12]

Energy Fuels has also been developing its Pine Nut mine located north of the Grand Canyon since 1986.

Ban on uranium mining near Grand Canyon National Park

In July 2009 Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar announced a two-year ban on new mining on federal land in an area of approximately 1 million acres (4,000 km2) surrounding Grand Canyon National Park. Although the ban is on all mining, the main effect is on exploration and development of breccia-pipe uranium deposits. Those claims on which commercial mineral deposits have already been discovered are exempt from the ban. During the two-year ban the Department of the Interior will study a proposed 20-year ban on new mining in the area.[13]

In January 2012, secretary Ken Salazar approved a 20-year ban on mining around the Grand Canyon. This decision preserves about “1 million acres near the Grand Canyon, an area known to be rich in high-grade uranium ore reserves” and has generated a number of different responses [14]

The ban is supported by the president of the League of Conservation voters, Gene Karpinski: "Extending the current moratorium on new uranium mining claims will protect drinking water for millions downstream.” Many environmental groups agree that such mining would endanger the Colorado River as a source of water not only for wildlife, but for tens of millions of people; Phoenix, Las Vegas and Los Angeles rely on the river for drinking water.[14] With areas of contamination already noted in United States environmental impact reports on old mining operations, opposition fears that allowing mining to expand and continue would increase the levels of contamination in the river.[15]

Supporters of the mining around the Grand Canyon argue that large-scale contamination from accidents involving mining are unlikely. According to an Arizona Geological survey, “60 metric tons of dissolved uranium is naturally carried by the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon in an average year".[16] J.E. Spencer, AZGS Senior Geologist, argues that in one hypothetical, worst-case scenario experiment, a truck carrying “thirty metric tons (66,000 pounds) of one-percent uranium ore” spilling and washing into the Colorado River increases the natural uranium level in the river by an insignificant amount.[16] Providing further data on uranium levels in the Colorado River, a 2010 United States Geological survey found that the river carries about 40 to 80 tons through the canyon each year.[16]

In 2011 more than 200 Arizona small businesses addressed postcards to Interior Secretary Ken Salazar sign the 20-year ban on new uranium mining near the Grand Canyon, to preserve thousands of tourism-related jobs.[17][17] President of the League of Conservation voters Gene Karpinski agreed that protecting the tourism industry, which relies on the Grand Canyon, is more economically important than mining near the canyon.[15] Coconino County Supervisor Carl Taylor argued that Uranium mining poses a great threat to tourism in the canyon and surrounding areas.[18] Some believe that one mining accident could be destructive for tourism in the highly popular park.[14] Interior Secretary Ken Salazar states that “the Grand Canyon attracts more than 4 million visitors a year and generates an estimated $3.5 billion in economic activity”.[14] Salazar also stated that people from the United States and even all over the world come to visit and see the Grand Canyon. He believes that allowing mining in this area to be pursued would negatively impact this tourism industry.[14]

Some argue that not allowing the mining to occur destroys years of resource development.[14] Hal Quinn, president and CEO of the National Mining Association states that banning mining in the Grand Canyon only deprives the United States of energy and minerals that are critical to the survival and strength of the US economy.[14] The mining industry agrees, believing that a ban on mining around the Grand Canyon would negatively impact Arizona's local economy and the United States’ energy independence.[14] Jonathan DuHamel states that a permanent ban on mining would eliminate hundreds of potential jobs. Former presidential candidate John McCain argues that opposition to the mining provoked by environmental groups who have the goal of killing mining and grazing jobs throughout Arizona.[15]

The increasing number of claims that began in 2006 was a direct result of the rising uranium prices that began that year.[18] Higher uranium prices encouraged mining companies to locate and mine new deposits around the canyon area. In 2011, when the price of uranium lowered about 35%, companies continued to explore the area.[18]

References

- Robert B. Scarborough (1981) Radioactive Occurrences and Uranium Production in Arizona, US Department of Energy, part 3, GJBX-143-(81).

- Roger C. Malan (1968) The uranium mining industry and geology of the Monument Valley and White canyon districts, Arizona and Utah, in Ore Deposits of the United States, 1933-1967, New York: American Institute of Mining Engineers, p.790-804.

- Robert B. Scarorough (1981) Radioactive Occurrences and Uranium Production in Arizona, part 3, US Department of Energy, GJBX-143(81), p.264.

- A.P. Butler Jr. and V.P. Byers (1969) Uranium, in Mineral and Water Resources of Arizona, Arizona Bureau of Mines, Bulletin 180, p.288.

- Andreas Mueller and Peter Halbach, The Anderson mine (Arizona)-an early diagenetic uranium deposit in Miocene lake sediments, Economic Geology, Mar.-Apr. 1983, p.2475-292.

- "Concentric Energy Advisors - Utility & Energy Consultants". Concentric Energy Advisors.

- Robert B. Scarborough (1981) Radioactive Occurrences and Uranium Production in Arizona, US Dept. of Energy, GJBX-143(81), p.93.

- Denison Mines, Arizona Strip uranium project, PDF file.

- N. Niemuth, "Arizona," Mining Engineering, May 2007, p.70.

- http://www.kpho.com/arizona/27163219/detail.html

- “Federal court rejects challenge to Energy Fuels Canyon mine,” Engineering & Mining Journal, 9 May 2015.

- Miriam Wasser, “Arizona uranium mine decision appealed by pllaintiiffs,” Phoenix New Times, 1 May 2015.

- "Two-year ban on mining near Grand Canyon imposed," Mining Engineering, September 2009, p.7.

- <https://www.usatoday.com/money/industries/environment/story/2012-01-09/grand-canyon-mining-ban/52466224/1>

- <http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2012/jan/09/grand-canyon-uranium-mining-banned>

- <http://repository.azgs.az.gov/uri_gin/azgs/dlio/1000>

- <http://www.wise-uranium.org/upusaaz.html>

- <http://www.grandcanyontrust.org/news/2012/02/grand-canyon-trust-uranium-campaign-chronicle/>