United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone

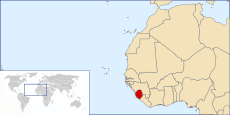

The United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone (UNAMSIL) was a United Nations peacekeeping operation in Sierra Leone from 1999 to 2006. It was created by the United Nations Security Council in October 1999 to help with the implementation of the Lomé Peace Accord, an agreement intended to end the Sierra Leonean civil war. UNAMSIL expanded in size several times in 2000 and 2001. It concluded its mandate at the end of 2005,[1] the Security Council having declared that its mission was complete.[2]

| |

| Abbreviation | Shalom |

|---|---|

| Formation | 22 October 1999 |

| Type | Peacekeeping Mission |

| Legal status | Completed |

| Headquarters | Freetown, Sierra Leone |

Head | Chief of Mission Daudi Ngelautwa Mwakawago

Chief Military Observer |

Parent organization | United Nations Security Council |

| Website | |

| Sierra Leone Civil War |

|---|

|

| Personalities |

| Armed forces |

| Attempts at peace |

|

| Political groups |

| Ethnic groups |

| See also |

The mandate was notable for authorizing UNAMSIL to protect civilians under imminent threat of physical violence (albeit "within its capabilities and areas of deployment") – a return to a more proactive style of UN peacekeeping.[3][4]

UNAMSIL replaced a previous mission, the United Nations Observer Mission in Sierra Leone (UNOMSIL). After 2005 the United Nations Integrated Office in Sierra Leone (UNIOSIL) began operations as a follow up to UNAMSIL. UNIOSIL's mandate was extended twice and ended in September 2008.

Conflict Background

The civil war began with the 1991 campaign by the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) to remove President Joseph Momoh from power. Illicit diamond trade played a central role in financing the conflict and multiple actors were present with outside intervention for both sides. The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) sent their Military Observer Group (ECOMOG) to defend the Momoh Government in 1991.[5] After a request from the Sierra Leone head of state, the UN Secretary-General sent an exploratory mission to Sierra Leone in December 1993. The results of the mission pushed forward the appointment of Berhanu Dinka as Special Envoy, who worked with the ECOWAS and the Organization of African Unity (OAU) to negotiate a peace settlement.[6] Nonetheless, intermittent peace negotiations failed to prevent military coups and several regime changes throughout the following decade. The Abidjan Peace Accord was an effort between Sierra Leone President Ahmad Tejan Kabbah and RUF leader Foday Sankoh, but ultimately the results were not honored and Kabbah faced a military coup months later. United Nations Security Council Resolution 1181 in July 1998 established the United Nations Observer Mission in Sierra Leone (UNOMSIL) with the goal of monitoring the security situation for an initial period of six months. In early January 1999, RUF rebels attacked and gained control over several areas in Freetown, the capital of Sierra Leone, but were swiftly ousted by ECOMOG.[7] The Lomé Peace Accord were signed by the belligerents on 7 July 1999 focused on amnesty for combatants and the transformation of the RUF into a political party.

Authorisation

On 20 August 1999, the UN expanded the number of military observers within Sierra Leone from 70 to 210.[8] UNAMSIL was established on 22 October 1999 and the UN presence expanded to 260 military observers and 6,000 military personnel. As part of Security Council resolution 1207, UNAMSIL aimed to assist with the implementation of the Lomé Accords. UNAMSIL was originally designed as a neutral peacekeeping force working in conjunction with ECOMOG, whose responsibility was the enforcement of the peace agreement. UNAMSIL relied on the presence of the ECOMOG, which was threatened when Nigerian President Obasanjo presented his intention to withdraw troops.[9] The first group of nearly 500 troops left Sierra Leone just weeks after the resolution on 2 September 1999 and although ECOMOG stopped the withdrawal soon after, about 2,000 Nigerian troops had already left.[10]

Mandate

According to Security Council Resolution 1270 of 22 October 1999 which established the operation, UNAMSIL had the following mandate:

- To cooperate with the Government of Sierra Leone and the other parties to the Peace Agreement in the implementation of the Agreement

- To assist the Government of Sierra Leone in the implementation of the disarmament, demobilization and reintegration plan

- To that end, to establish a presence at key locations throughout the territory of Sierra Leone, including at disarmament/reception centres and demobilization centres

- To ensure the security and freedom of movement of United Nations personnel

- To monitor adherence to the ceasefire in accordance with the ceasefire agreement[11] (whose signing was witnessed by Jesse Jackson)

- To encourage the parties to create confidence-building mechanisms and support their functioning

- To facilitate the delivery of humanitarian assistance

- To support the operations of United Nations civilian officials, including the Special Representative of the Secretary-General and his staff, human rights officers and civil affairs officers

- To provide support, as requested, to the elections, which are to be held in accordance with the present constitution of Sierra Leone[12]

In February 2000 the mandate had been revised to include the following tasks:

- To provide security at key locations and Government buildings, in particular in Freetown, important intersections and major airports, including Lungi airport

- To facilitate the free flow of people, goods and humanitarian assistance along specified thoroughfares

- To provide security in and at all sites of the disarmament, demobilization and reintegration programme

- To coordinate with and assist, the Sierra Leone law enforcement authorities in the discharge of their responsibilities

- To guard weapons, ammunition and other military equipment collected from ex-combatants and to assists in their subsequent disposal or destruction[13]

Upon withdrawal, the remaining staff in Freetown were transferred to United Nations Integrated Office in Sierra Leone (UNIOSIL).[14]

Mission Structure

Strength

The initial UNAMSIL mandate of October 2000 called for 6,000 military personnel which was later expanded to 11,000 when the mission was upgraded by Chapter VII to allow troops to have enforcing capabilities.[15] UNAMSIL was later expanded to 13,000 personnel in May 2000 and finally authorized in March 2001 to its maximum strength of 17,500 military personnel including 260 military observers and 170 police personnel by Security Council resolution 1346. The maximum deployment strength of UNAMSIL was reached in March 2002 with 17,368 military personnel, 87 UN police, and 322 international and 552 local civilian personnel.[16]

Leadership

Special Representative of the Secretary-General and Chief of Mission:

| Daudi Ngelautwa Mwakawago | December 2003 – December 2005 | |

| Alan Doss | July 2003 – December 2003 | |

| Oluyemi Adeniji | December 1999 – July 2003 | |

Force Commander and Chief Military Observer:

| Sajjad Akram | October 2003 – September 2005 | |

| Daniel Opande | November 2000 – September 2003 | |

| Vijay Kumar Jetley | December 1999 – September 2000 | |

Police Commissioner:

| Hudson Benz | March 2003 – September 2005 | |

| Joseph Dankwa | December 1999 – February 2003 | |

Composition

Troop Contributions

The following countries provided Military Personnel:

The following countries provided Police Personnel:

Financial Contributions

The total estimated cost for this mission is $2.8 billion

Expenditures:

| 1 July 1999 to 30 June 2000 | $264.9 million |

| 1 July 2000 to 30 June 2001 | $494.4 million |

| 1 July 2001 to 30 June 2002 | $617.7 million |

| 1 July 2002 to 30 June 2003 | $603.1 million |

| 1 July 2003 to 30 June 2004 | $448.7 million |

| 1 July 2004 to 30 June 2005 | $265.0 million |

Approved budget:

| 1 July 2005 to 30 June 2006 | $107.5 million |

Operation

Disarmament, Demobilization, and Reintegration (DDR)

Disarmament, demobilization and reintegration (DDR) programs for ex-combatants were central to peace resolutions in the Sierra Leone context. The first phase of DDR that was designed to be carried out by the government with the help of ECOMOG and UNDP was disrupted by a rebel attack in Freetown on 6 January 1999. The second phase—part of the Lome Agreement--- created a joint operation plan between multiple actors to establish demobilization centers. Nearly 19,000 combatants were disarmed during this period before the May 2000 disturbances.[17] Disarmament required coordination with the warring groups and leaders, including the cooperation of Foday Sankoh. UNAMSIL secured disarmament centers and facilitated the registration of ex-combatants into the DDR program. UNICEF worked parallel to UNAMSIL with the main task of the demobilization and integration of child soldiers who had been recruited into rebel groups.[18] There were disruptions at camps and in Freetown over the delayed payment of DDR allowances,[19] but towards the latter part of the mission, the DDR program saw many improvements, including better information dissemination.Radio UNAMSIL was a central aspect of the mission's public information strategy.[20] UNAMSIL led Pakistan contingent was deployed in eastern province of Kono. Pakistani contingent were extremely effective and were able to restore peace and order in the area. The effort undertaken by the Pakistani Contingent under the name of 'Hearts and Minds Winning Campaign' proved very successful and helped integrate the communities and people at large. The Pak Batt - 8 led by Lieutenant Colonel Zafar and Major Qavi Khan earned a true acclaim of the people of Koidu. Both the officers of the Pakistan Army, in the Pakistani Contingent, worked relentlessly to affect the cross-section of the community from building schools, churches and mosques to organising sports competitions for children and workshops for women. They impacted on the daily lives of the people in a way that left a lasting imprint on the lives of the people of Koidu.

Civilian Police

The Military Reintegration Plan aimed to the rebuild the security services of Sierra Leone. The goal was to reach a projected strength of 9,500 police officers by 2005. By March 2003, the program reached between 6,000 and 7,000 police officers, a number lower than expected due to high attrition rate. The mission focused efforts on recruiting new cadets and expanding the capacity of the Police Training School.[21] By 2005, the police force reached the goal of 9,500 officers with UNAMSIL training some 4,000 in routine field training and other programs including computer literacy, human rights, and policing diamond mining.[22]

Hostage Crisis

RUF leaders in the Northern province had displayed prior resistance to the DDR efforts and arrived at a DDR reception center in Makeni on 1 May 2000 demanding ex-combatants be released. When UN personnel refused, the RUF combatants detained 3 UNAMSIL military observers and 4 Kenyans from the peacekeeping force. More RUF engagement the next day attempted to disarm UNAMSIL and sparked similar efforts in other areas. Personnel and materials were intercepted and within days, the RUF had seized nearly 500 UN personnel.[23] British troops were deployed on 7 May to facilitate the evacuation of national, but the additional presence boosted the confidence of UNAMSIL. The former colonial power of Sierra Leone deployed about 900 forces with a combate mandate.[24] One of the focal demands of the RUF was the release of Foday Sankoh and other leaders held by the Sierra Leone government.[25] As a result of strong international and regional pressure, 461 UN personnel were released through Liberia between May 16 and 28.[26] This release came about due to mediation through Liberian president Charles Taylor, the main foreign backer of the RUF. A later rescue mission in July successfully extracted 222 Indian peacekeepers and 11 military observers who were surrounded at Kailahun.[27] UN personnel grew to over 13,000 amist security threats at this time.[28]

Abuja Cease fire agreement November 2000

The Freetown government emphasized pursuing a counter strategy against the rebels and not lessening the war effort, while UNAMSIL diverging interests pushed for another ceasefire.[29] Attempts by UNAMSIL and ECOWAS to establish contact with RUF succeeded in October 2000 when RUF leaders expressed interest in a ceasefire and returning to the Lomé Agreement. A meeting convened on 10 November 2001 leading to a ceasefire between the government and RUF that included the agreement to return all seized UNAMSIL weapons and the immediate resumption of DDR.[30] UNAMSIL was designated a monitoring role allowed access to all parts of the country and both parties agreed to the unrestricted movement of humanitarian workers and resources. Although mixed signals were presented through the media, RUF leadership reiterated their commitment to the agreement.

End of War

On 2 May 2001 the second meeting of the Committee of Six of the ECOWAS Mediation and Security Council addressed the ceasefire that had been maintained since the previous November.[31] Both parties reiterated the commitment for the free movement of persons and the newly trained Sierra Leone Army, trained by UK personnel, would help monitor the cease fire. The meeting addressed the cross-border attacks from Guinea and the transformation of the RUF into a political party. Acting upon the November 2000 agreement, all seized UN arms were returned by 31 May 2001.[32] With Charles Taylor facing sanctions, a diamond ban, and international pressure as well as the loss of troops and prestige in the Guinea attacks, these factors severely hindered Taylor's ability to sustain the war outside his borders.[33] Losing the backing of a powerful neighbor and a series of defeats, a weak RUF agreed to treaties and failed to incite further violence to the same extent. On 18 January 2002, Sierra Leone president Ahmed Tejan Kabbah officially declared the end of the civil war that had spanned over a decade.[34] There were a total of 192 UN fatalities: 69 troops, 2 military observers, 2 international civilians, 16 local civilians, 1 police, and 2 others.[35]

After the contribution made by the Bangladesh UN Peacekeeping Force in the Sierra Leone Civil War, the government of Ahmad Tejan Kabbah declared Bengali an honorary official language in December 2002.[36][37][38][39]

Withdrawal

On 30 June 2005, United Nations Security Council Resolution 1610 extended UNAMSIL's mandate for a final six months with plans to withdraw on 31 December 2005. Two months later, resolution 1620 established the United Nations Integrated Office in Sierra Leone (UNIOSIL). As of November 2005, the size and strength of UNAMSIL had significantly shrunk with a total of 1,043 uniformed personnel still within the country including 944 troops, 69 miliary observers, 30 police, 216 international civilian personnel, and 369 local civilian staff.[40] UNIOSIL become operational on January first 2006; the follow-up mission strategy was developed jointly with UNAMSIL and the UN country team to focus on poverty reduction through the UN's development framework as well as maintaining peace through economic good governance. UNIOSIL ended in September 2008 and was replaced by the United Nations Integrated Peacebuilding Office in Sierra Leone (UNIPSIL). The Security Council unanimously agreed to withdraw UNIPSIL by 31 March 2014 although the UN country office will remain present to continue to support the constitutional review process. Former UN Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon travelled to Freetown, Sierra Leone to mark the closure of UNIPSIL where he stated: “Sierra Leone represents one of the world’s most successful cases of post-conflict recovery, peacekeeping and peacebuilding.”[41]

Legacy

The establishment of UNAMSIL constituted a policy shift in UN peacekeeping as it was one of the first missions where UN troops were permitted to use force. Canadian diplomats in the Security Council and the government of Sierra Leone advocated for this change, while all other Security Council members aimed for a Chapter VI peacekeeping mission. The Canadian mission to the Security Council hosted General Roméo Dallaire, commander for the UN during 1994 Rwandan Genocide, who is a spokesperson for force enforcing capabilities for troops.[42] Chapter VII of the UN charter outlines the power of the Security Council to maintain peace through “measures it deems necessary”, including military power.[43] When the Security Council changed the mandate of UNAMSIL, they outlined the ability to: “take the necessary action, in the discharge of its mandate, to ensure the security and freedom of movement of its personnel and, within its capabilities and areas of deployment, to afford protection to civilians under imminent threat of physical violence”[44] The ability to use force was a powerful deterrent in the illicit diamond trade that fueled the conflict.[45] UNAMSIL created buffer zones between skirmishes in the mining district of Kono and was successful in gaining authority over diamond rich areas. Before UNAMSIL, the Security Council mainly invoked Chapter VII to authorize force to other non-UN actors. However, after the Chapter VII force mandate for Sierra Leone, it has been similarly utilized in sixteen other peacekeeping missions since 1999.[46] Despite the extreme setbacks the mission faced with the capture of over 500 UN personnel, the Security Council did not withdraw the mission. In the wake of Rwanda and Somalia, this represented another shift with sustained interest from the Security Council and bilateral involvement of the United Kingdom pushing the mission to completion.

References

- United Nations Security Council Resolution 1610. S/RES/1610(2005) page 1. (2005) Retrieved 2007-11-13.

- United Nations Security Council Verbotim Report 5334. S/PV/5334 page 2. Mr. Mwakawago 20 December 2005. Retrieved 2007-11-13.

- United Nations Security Council Verbotim Report 4099. S/PV/4099 page 6. Mr. Fowler Canada 7 February 2000. Retrieved 2007-11-13.

- BELLAMY, ALEX J.; HUNT, CHARLES T. (2015). "Twenty-first century UN peace operations: protection, force and the changing security environment". International Affairs. 91 (6): 1277–1298. 1280. doi:10.1111/1468-2346.12456. ISSN 0020-5850.

- Galic, Mirna (2001). "Into the Breach: An Analysis of the United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone". Stanford Journal of International Relations. 3 (1).

- "UNOMSIL". UN.org. United Nations.

- Koinage, Jeff (13 January 1999). "Freetown in flames as rebels retreat". Independent.

- "UNOMSIL". UN.org. United Nations.

- Galic, Mirna (2001). "Into the Breach: An Analysis of the United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone". Stanford Journal of International Relations. 3 (1).

- "Regional Peacekeeping Force: Lome Peace Agreement". Peace Accords Matrix. University of Notre Dame.

- United Nations Security Council Document 585. S/1999/585 18 May 1999. Retrieved 2007-11-13.

- United Nations Security Council Resolution 1270. S/RES/1270(1999) page 2. 22 October 1999. Retrieved 2007-11-13.

- United Nations Security Council Resolution 1289. S/RES/1289(2000) page 3. 7 February 2000. Retrieved 2007-11-13.

- United Nations Security Council Verbotim Report 5334. S/PV/5334 page 2. Mr. Mwakawago 20 December 2005. Retrieved 2007-11-13.

- Bernath, Clifford; Nyce, Sayre (2004). "Peacekeeping Success: Lessons Learned from UNAMSIL". Journal of International Peacekeeping. 8: 119–142. doi:10.1163/18754112-90000008.

- "UNAMSIL- Facts and Figures". Peacekeeping.org. United Nations.

- Bernath, Clifford (2004). "Peacekeeping Success: Lessons Learned from UNAMSIL". Journal of International Peacekeeping. 8: 119–142. doi:10.1163/18754112-90000008.

- "Eighth report of the Secretary General on the United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone". United Nations. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - "Fourth report of the Secretary-General on the United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone". United Nations.

- "Fifth report of the Secretary-General on the United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone". United Nations.

- "Seventeenth report of the Secretary-General on the United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone". United Nations.

- "Twenty-seventh report of the Secretary-General on the United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone". United Nations.

- "Fourth report of the Secretary-General on the United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone". United Nations.

- Bernath, Clifford (2004). "Peacekeeping Success: Lessons Learned from UNAMSIL". Journal of International Peacekeeping. 8: 119–142. doi:10.1163/18754112-90000008.

- Farah, Douglas (19 July 2000). "UN rescues hostages in Sierra Leone". The Guardian.

- "Fifth report of the Secretary-General on the United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone". United Nations.

- "Fifth report of the Secretary-General on the United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone". United Nations.

- Farah, Douglas (19 July 2000). "UN rescues hostages in Sierra Leone". The Guardian.

- McGreal, Chris (16 May 2000). "Threats to Sierra Leone hostages splits UN". The Guardian.

- "Eighth report of the Secretary-General on the United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone". United Nations.

- "Sierra Leone ceasefire review meeting concludes in Abuja". United Nations. 3 May 2001.

- "Eighth report of the Secretary-General on the United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone". United Nations.

- Bernath, Clifford (2004). "Peacekeeping Success: Lessons Learned from UNAMSIL". Journal of International Peacekeeping. 8: 119–142. doi:10.1163/18754112-90000008.

- "Sierra Leone Leaders Declare War Over". PBS News Hour. 18 January 2002.

- "UNAMSIL- Facts and Figures". Peacekeeping.org. United Nations.

- "How Bengali became an official language in Sierra Leone". The Indian Express. 2017-02-21. Retrieved 2017-03-22.

- "Why Bangla is an official language in Sierra Leone". Dhaka Tribune. 23 Feb 2017.

- Ahmed, Nazir (21 Feb 2017). "Recounting the sacrifices that made Bangla the State Language".

- "Sierra Leone makes Bengali official language". Pakistan. 29 Dec 2002. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013.

- "Twenty-seventh report of the Secretary-General on the United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone". United Nations.

- "Closing political office in Sierra Leone, UN shifts focus to long term development". United Nations. 5 March 2014.

- Howard, Lise Morje; Kaushlesh Dayal, Anjali (2017). "The Use of Force in UN Peacekeeping". International Organization. 72 (1): 71–103. doi:10.1017/s0020818317000431.

- "Chapter VII". UN.org. United Nations. 2015-06-17.

- "Fourth report of the Secretary-General on the United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone". United Nations.

- "UNAMSIL Press Briefing, 21 Dec 2001". United Nations. 21 December 2001.

- Howard, Lise Morje; Kaushlesh Dayal, Anjali (2017). "The Use of Force in UN Peacekeeping". International Organization. 72 (1): 71–103. doi:10.1017/s0020818317000431.

External links

- UNAMSIL at UN.org

- UNIOSIL, the follow-up peace consolidation mission to UNAMSIL, at UN.org

- Detailed description of Op Khukri, launched by UN forces to rescue more than 200 peacekeepers from RUF