Battle of Bhaktapur

The Battle of Bhaktapur was the final campaign in the Gorkha conquest of Nepal.[1] It took place in Bhaktapur in 1769, and resulted in the victory of the Gorkhali king Prithvi Narayan Shah, giving him control of the entire Kathmandu Valley and adjoining areas.

| The Battle of Bhaktapur | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Gorkhali conquest of Nepal | |||||||

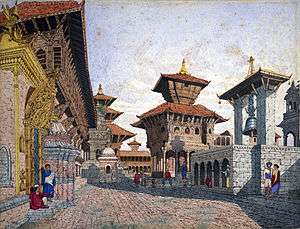

Bhaktapur Durbar Square, the royal palace complex, in 1854. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Kingdom of Nepal | Gorkha Kingdom | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Ranajit Malla |

Prithvi Narayan Shah Vamsharaj Pande Surapratap Shah Swarup Singh Karki | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 3000-8000 | 20,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

2,001 killed 501 houses set on fire | Unknown | ||||||

Shah thus established the Shah dynasty in Nepal, and the rule of the indigenous Newars came to an end.[2] The defeated king of Bhaktapur, Ranajit Malla, was sent into exile in India.[3][4]

The blockade

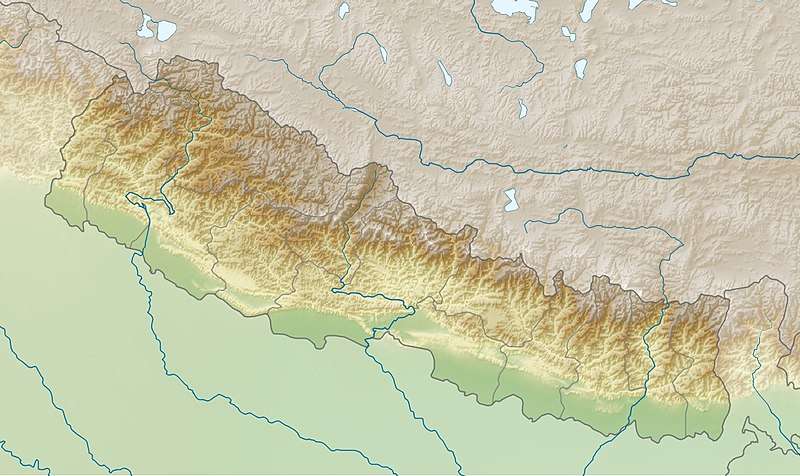

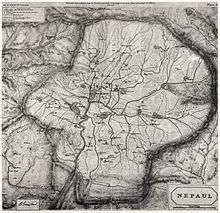

Bhaktapur (alternative names: Khwopa Desa ख्वप देस, Bhadgaon) was one of the three capital cities in the Malla confederacy of Nepal, the other two being Kathmandu and Lalitpur. The eastern boundary of the kingdom of Bhaktapur extended to a distance of five-six days' journey to the east. The city contained 12,000 households.[5]

The Gorkhalis desired the Kathmandu Valley due to its rich culture, trade, industry and agriculture.[6] In 1736, the Gorkhali king Nara Bhupal Shah launched an attack on Nuwakot, a border town and fort in the northwest of the valley, and was roundly defeated.[7] His son Prithvi Narayan Shah became king in 1742 and resumed the campaign.[8][9]

As Shah knew he would not be able to take over the valley by force, he decided to impose an embargo with a view to starve it. His forces occupied strategic passes in the surrounding hills, and strangled the vibrant trade between Tibet and India that passed through the valley. Blockade runners found with salt or cotton on them were hung on the road.[10]

In 1744, the Gorkhalis took Nuwakot on the trans-Himalayan trade route.[11] In 1762 and 1763, they overran Makwanpur and Dhulikhel respectively, surrounding the Kathmandu Valley from the west, south and east.[12]

In a bid to cause a famine, Shah prevented any grain from passing into the valley, and blockade runners were hung from the trees on the roads.[13] The prolonged siege forced the king of Kathmandu to appeal to the British East India Company for help. In August 1767, Captain George Kinloch led a British force towards the valley to rescue its beleaguered inhabitants.[14] He reached within 75 km of Kathmandu and captured the forts at Sindhuli and Hariharpur, but was forced to retreat after supplies ran out and his troops mutinied.[15][16]

The final battle

Wearing down the Newars with a continuous embargo and propaganda campaign, Shah captured Kirtipur, Kathmandu and Lalitpur in succession. He then marched upon Bhaktapur in 1769. The kings of Kathmandu and Lalitpur, Jaya Prakash Malla and Tej Narasingh Malla, had sought refuge in Bhaktapur after losing their kingdoms. The three kings joined forces to do battle with the Gorkhali army, but they were defeated, again due to betrayal by the nobles.

The soldiers of the treacherous nobles opened the city gates and let the Gorkhalis in. Shah's troops possessed muskets, in addition to swords and bows and arrows. There was fierce fighting in front of the palace, but the invaders finally broke through the gates.[17]

According to the journal kept at the monastery of Jana Baha, Kathmandu, Shah's troops captured Bhaktapur on the night of November 25, 1769. They killed 2,001 people and set 501 houses on fire.[18]

Ranajit Malla was allowed to leave for Varanasi because of his age. Jaya Prakash died from a bullet wound while Tej Narasingh was kept in chains till his death.[19]

The conquest of Bhaktapur marked the end of the Malla dynasty and the rise of the Shah dynasty in Nepal. Shah reign lasted until 2008 when the country became a republic.[20]

Malla's departure

King Ranajit Malla of Bhaktapur was so distressed that he was driven to compose a lament filled with regret at having trusted the Gorkhali king. According to eyewitnesses, Malla wept uncontrollably when he paused at the hilltop of Chandragiri on the valley rim for one last look at his former kingdom. From Chandragiri, the route descends south and exits the valley to continue on to India.[21]

References

- Hamilton, Francis Buchanan (1819). An Account of the Kingdom Of Nepal and of the Territories Annexed to This Dominion by the House of Gorkha. Edinburgh: Longman. Retrieved 22 November 2012. Page 186.

- Waller, Derek J. (2004). The Pundits: British Exploration Of Tibet And Central Asia. University Press of Kentucky. p. 171. ISBN 9780813191003.

- Giuseppe, Father (1799). Account of the Kingdom of Nepal. London: Vernor and Hood. p. 322. Retrieved November 22, 2012.

- Malla, Sampada & Rai, Dinesh (January 2006). "Where Have All The Mallas Gone?: The Descendants of the Mallas". ECS Nepal. Archived from the original on 18 December 2011. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- Giuseppe, Father (1799). Account of the Kingdom of Nepal. London: Vernor and Hood. p. 308. Retrieved November 7, 2012.

- Raj, Yogesh (2012). "Introduction". Expedition to Nepal Valley: The Journal of Captain Kinloch (August 26-October 17, 1767). Kathmandu: Jagadamba Prakashan. p. 7. ISBN 9789937851800.

- Northey, William Brook and Morris, Charles John (1928). The Gurkhas: Nepal-Their Manners, Customs and Country. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 9788120615779. Pages 30-31.

- Stiller, Ludwig F. (1968). Prithwinarayan Shah in the light of Dibya Upadesh. Catholic Press. p. 39.

- Singh, Nagendra Kr (1997). Nepal: Refugee to Ruler: A Militant Race of Nepal. APH Publishing. p. 125. ISBN 9788170248477. Retrieved December 6, 2012.

- Giuseppe, Father (1799). Account of the Kingdom of Nepal. London: Vernor and Hood. p. 317. Retrieved November 23, 2012.

- Shrestha, Sanyukta (27 July 2012). "Nepali history from new perspectives". Republica. Archived from the original on 5 August 2012. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- Raj, Yogesh (2012). "Introduction". Expedition to Nepal Valley: The Journal of Captain Kinloch (August 26-October 17, 1767). Kathmandu: Jagadamba Prakashan. p. 5. ISBN 9789937851800.

- Giuseppe, Father (1799). Account of the Kingdom of Nepal. London: Vernor and Hood. p. 317. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- Chatterji, Nandalal (1939). "The First English Expedition to Nepal". Verelst's Rule in India. Indian Press. p. 21. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- Raj, Yogesh (2012). "Introduction". Expedition to Nepal Valley: The Journal of Captain Kinloch (August 26-October 17, 1767). Kathmandu: Jagadamba Prakashan. pp. 13–14. ISBN 9789937851800.

- Shrestha, Sanyukta (27 July 2012). "Nepali history from new perspectives". Republica. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- Wright, Daniel (1990). History of Nepal. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. p. 255. Retrieved December 7, 2012.

- Shakya, Raja (2005). Jana Baha Dyah ya Shanti Saphu (Ghatanavali). Kathmandu: Premdharma Pithana. p. 60. ISBN 99946-56-97-X.

- Giuseppe, Father (1799). Account of the Kingdom of Nepal. London: Vernor and Hood. p. 322. Retrieved November 23, 2012.

- "Nepal's Gorkha kingdom falls". The Times of India. 2 June 2008. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- Dhungel, Ramesh K. (January 2007). "Anguished Cry of a Defeated Ruler: A Raga Song Composed by Ranajit Malla". Contributions to Nepalese Studies. Retrieved 22 February 2013. Pages 95-102.

y