Typhoon Noru (2017)

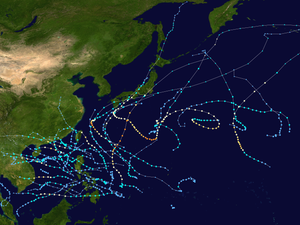

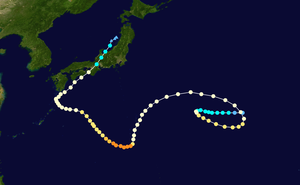

Typhoon Noru was the second-longest-lasting tropical cyclone of the Northwest Pacific Ocean on record—behind only 1986's Wayne and tied with 1972's Rita—and the second-most-intense tropical cyclone of the basin in 2017, tied with Talim.[nb 1][1][2] Forming as the fifth named storm of the annual typhoon season on July 20, Noru further intensified into the first typhoon of the year on July 23. However, Noru began to interact with nearby Tropical Storm Kulap on July 24, executing a counterclockwise loop southeast of Japan. Weakening to a severe tropical storm on July 28, Noru began to restrengthen as it turned sharply to the west on July 30. Amid favorable conditions, Noru rapidly intensified into the season's first super typhoon, and reached peak intensity with annular characteristics on July 31. In early August, Noru underwent a gradual weakening trend while curving northwestwards and then northwards. After stalling off the Satsunan Islands weakening to a severe tropical storm again on August 5, the system began to accelerate northeastwards towards the Kansai region of Japan, making landfall in Wakayama Prefecture on August 7. Noru became extratropical over the Sea of Japan on August 8, and dissipated one day later.

| Typhoon (JMA scale) | |

|---|---|

| Category 4 super typhoon (SSHWS) | |

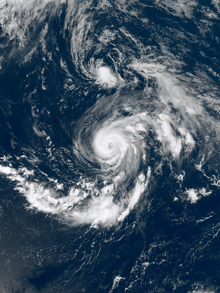

Typhoon Noru at peak intensity south of Iwo Jima on July 31 | |

| Formed | July 19, 2017 |

| Dissipated | August 9, 2017 |

| (Extratropical after August 8) | |

| Duration | 2 weeks and 6 days |

| Highest winds | 10-minute sustained: 175 km/h (110 mph) 1-minute sustained: 250 km/h (155 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 935 hPa (mbar); 27.61 inHg |

| Fatalities | 2 total |

| Damage | $100 million (2017 USD) |

| Areas affected | Japan |

| Part of the 2017 Pacific typhoon season | |

Noru was responsible for two deaths in Kagoshima Prefecture, and at least $100 million (2017 USD) in damages in Japan.[3]

Origins

A non-tropical low formed about 700 km (435 mi) north-northwest of Wake Island at around 00:00 UTC on July 18, 2017,[4] which transitioned into a tropical depression about one day later.[5] In the afternoon of July 19, the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) began issuing tropical cyclone warnings on the system, expecting a tropical storm within 24 hours.[6] Although outflow was weak for the partially organized system at that time, low vertical wind shear and sea surface temperature (SST) at 29 ºC were conducive to development.[7] Originally retaining some subtropical characteristics, it began transitioning into a fully tropical and warm-core system; therefore, the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) issued a Tropical Cyclone Formation Alert to the system early on July 20, when fragmented deep convective bands had wrapped around its broad low-level circulation center (LLCC). A point source positioned over the center also improved outflow aloft.[8] At 12:00 UTC, the system intensified into the fifth Northwest Pacific tropical storm of 2017,[5] which was assigned the international name Noru half a day later by the JMA operationally.[9] Besides, the JTWC upgraded the system to a tropical depression at 21:00 UTC.[10] 12 hours later, the JTWC upgraded Noru to a tropical storm, despite its partially exposed LLCC; at the same time, it started tracking westward along the southwest periphery of the subtropical ridge (STR) positioned to the northeast.[11]

Noru struggled to intensify significantly for two days owing to relatively low ocean heat content values and its asymmetric structure,[12] until it developed into a severe tropical storm at around 18:00 UTC on July 22.[5] Subsequently, Noru slowed down and remained stationary, due to a complex steering environment consisting of ridging on three sides. The steering flow also transitioned from a subtropical ridging to the west to a near equatorial ridge to the south of the system. Noru rapidly intensified into the first typhoon of 2017 around 12:00 UTC on July 23,[13] marking the latest occurrence of the first typhoon since 1998.[14] It featured a 20 km (12 mi) diameter pinhole eye that embedded in an extremely compact core located about 900 km (560 mi) east of the Bonin Islands, thanks to moderate eastward outflow, anomalously warm SSTs and low vertical wind shear.[15] After that, the eye repeatedly reappeared and filled due to increasing vertical wind shear offset by improving poleward outflow into the upper-low associated with Tropical Storm Kulap. Noru also started to track east-southeastward under the steering influence of a near equatorial ridge to the south.[16][17]

Interaction with Tropical Storm Kulap

On July 24, a Fujiwhara interaction between Noru and Kulap started.[18] As a result, Kulap became directly located to the north of Noru early on July 25, and this situation allowed cold dry air to intrude along the western and southern periphery of the typhoon, making Noru weaken slightly with the significantly shallower convective core. The primary steering influence for Noru was still a near equatorial ridge to the south, but another ridge was also building in to the east, turning Noru northeastward and then northward.[19] Although vertical wind shear relaxed somewhat with the robust eastward outflow channel on July 26, the reduction of mid-level relative humidity and slightly depressed SSTs at 26 °C to 27 °C tempered intensification and even eroded the convective structure.[20] Having finished a cyclonic loop and tracking west-northwestward along the southern periphery of a deep-layered ridge to the northeast, Noru showed some signs of transitioning to a hybrid system, with an upper-level low nearby and a thermal structure more indicative of a subtropical storm.[21] However, Noru reformed a 35 km (20 mi) diameter eye late on the same day, and while dry air was still entrenched across the southern portion of the typhoon, the extent of the dry air had shrunk and the moisture envelope was expanding, forming a hospitable cocoon for the system to reside in.[22]

On July 27, Noru began to track westward along the southern periphery of a deep-layered ridge to the northeast. The upper-level environment was extremely complex, with a tropical upper tropospheric trough (TUTT) cell having developed just to the southwest, another upper-level low to the southeast and an induced anticyclone just to the south and extending over Noru. The aforementioned TUTT cell to the southwest was also providing a weak source of outflow. Moreover, the combination of the complex upper-level outflow and low vertical wind shear was helping Noru to maintain intensity.[22] At around 00:00 UTC on July 28, Noru slightly weakened into a severe tropical storm when approaching the Bonin Islands.[5] Dry air completely surrounded the system with weak convection wrapping around a ragged eye; moreover, vertical wind shear was high, but the shear vector was in general alignment with the storm motion, with resultant relative shear values in the low to moderate range.[23] At the same time, the steering flow transitioned to the subtropical ridge centered over the East China Sea, causing Noru to track southwestward along the eastern boundary of this STR. Despite warmer SSTs at 28 °C to 29 °C which supported intensification for Noru in the area, the complex upper-level environment with a TUTT cell to the southeast and a ridge far to the north combining limit outflow, while dry air continued enveloping the typhoon and isolating it from any significant moisture.[24]

Re-intensification and peak intensity

Noru reformed an eye at around 09:00 JST (00:00 UTC) on July 29 while situated 70 km (45 mi) to the east of Chichijima, the largest Ogasawara island.[25] Based on the observations from Iwo To, the JTWC downgraded Noru to a tropical storm at around 18:00 UTC, at which time the system was tracking directly southward along the eastern periphery of an extension of the STR positioned to the west.[26] Early on July 30, Noru began to improve its convective structure, making both of the JMA and the JTWC upgrade Noru to a typhoon again.[5][27] Over the following 24 hours, Noru rapidly intensified, and the JTWC reported that it had become a Category 4 super typhoon about 225 km (140 mi) south of Iwo To at around 18:00 UTC, with one-minute sustained winds at 250 km/h (155 mph), though operationally it was put at Category 5 strength with winds at 260 km/h (160 mph). The typhoon took on annular characteristics, with a symmetric ring of deep convection surrounding a 30 km (15 mi) well-defined eye and fairly uniform cloud top temperatures. Environmental conditions were favorable with radial outflow, enhanced by a poleward outflow channel into the TUTT and a subtropical jet to the east-northeast. Noru's previous southward motion also led itself to the warmer area with SSTs at 29 °C to 30 °C, favoring intensification. At this time, Noru began to drift westward within a competing steering environment.[28]

On July 31, Noru reached its peak intensity at around 00:00 UTC with ten-minute sustained winds at 175 km/h (110 mph) and the central pressure at 935 hPa (27.61 inHg).[5] It remained an impressively annular system with a clear eye but lacking banding features, yet the JTWC downgraded it to a typhoon in the afternoon because of recently warming cloud tops.[29] Traveling northwestward over an area of low ocean heat content and isolated from well-defined outflow, Noru's gradual weakening trend became more evident early on the next day, which is also indicated by the JMA.[5] A microwave imagery depicted a weakened eyewall, while the eye was temporarily not as clear as before.[30] Since late August 1, Noru presented a 95 km (60 mi) diameter large but ragged eye, yet the convective ring surrounding the eye gradually elongated, especially on the northwestern quadrant;[31] meanwhile, microwave imageries even depicted a break from the northwestern portion of the eyewall. Noru was establishing a poleward outflow channel that tapped into a passing mid-latitude trough located to the north on August 2, and a strong near-equatorial ridge was steering the typhoon towards a weak area in the subtropical ridge to the northwest, being the result of that passing mid-latitude trough.[32]

Landfall and dissipation

The ragged eye of Noru became enormous on August 3, with the diameter about 110 km (70 mi). Despite maintaining a good poleward outflow channel into an upper-level low to the northeast, the mid-latitude trough just to the northwest caused subsidence along the northwest quadrant and offset the favorable conditions including low vertical wind shear and warm SSTs, making deep convective bands shallower more and more.[33] Having tracked westward relatively faster for one day, Noru slowed down again and turned northwestward on August 4, along the southern periphery of a deep-layered subtropical ridge over the Korean Peninsula and western Japan. Deep convection in the northern portion was very shallow early on the same day that prompted the JTWC reporting a partially exposed system.[34] In the afternoon, convective bands re-intensified and surrounded a 70 km (45 mi) eye, yet the JMA radar depicted a much larger eye, with the diameter about 95 km (60 mi) to 110 km (70 mi).[35] On August 5, deep convective banding presented predominantly in the southern semi-circle of Typhoon Noru, owing to strong equatorward outflow and the terrain of Kyushu as well as the Ōsumi Islands. In spite of moderate vertical wind shear, the very warm SSTs at 31 °C of the Kuroshio still helped sustain the strength of Noru.[36] However, the system weakened into a severe tropical storm again about noon when the eye had completely deteriorated,[5] as an extension of the subtropical ridge was suffocating the typhoon on the northern periphery, resulting in the deteriorating poleward outflow channel.[37]

Noru remained almost stationary and looping around Yakushima until it accelerated northeastward off the southeastern coast of Kyushu on August 6, along the western boundary of a deep-layered ridge extension located to the southeast.[38] While the eye was struggling to reform, a strong convective structure started to wrap around a growing ragged eye feature later, over the SSTs at 29 °C.[39] On August 7, Noru passed near Muroto, Kōchi at 10:00 JST (01:00 UTC) on August 7 and made landfall over the northern part of Wakayama Prefecture at 15:30 JST (06:30 UTC).[40] Both of the JMA and the JTWC downgraded Noru to a tropical storm at around 24:00 JST (15:00 UTC), for the weakening system tracked over the Japanese Alps.[41][42] Noru emerged over the Sea of Japan from Toyama Prefecture at around 05:00 JST on August 8 (20:00 UTC on August 7) and then continued weakening, as deep convection had gradually deteriorated because of the mountainous terrain.[40] Thus, the JTWC downgraded Noru to a tropical depression about five hours later and issued their final warning owing to the poorly-defined and disorganized LLCC in the afternoon.[43][44] Noru subsequently became an extratropical cyclone at around 21:00 JST (12:00 UTC), before the system was declared dissipated by the JMA on August 9.[5]

Preparation and impact

In Japan, hundreds of flights were cancelled ahead of the storm, and thousands of people were moved to evacuation zones.[45]

As of August 7, two people had been killed by the passage of Typhoon Noru, both in Kagoshima Prefecture.[46][45] One man died due to Noru's high winds. The other Noru victim was a fisherman.[45] Total economic losses in Japan were counted to be US$100 million.[3]

See also

- Other typhoons named Noru

- Typhoon Roke (2011)

- Typhoon Halong (2014)

- Typhoon Lionrock (2016)

- Typhoon Malakas (2016)

- Typhoon Jongdari (2018)

Notes

- The Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) officially defines the duration as the period of the tropical storm intensity or higher. Should a tropical storm weakens into a tropical depression and intensifies into a tropical storm again, the TD period will be included.

References

- "長寿台風 (統計期間:1951年~2017年第12号まで)" (in Japanese). Japan Meteorological Agency. Retrieved October 6, 2017.

- Kitamoto, Asanobu. "Typhoon List by Track Information". Digital Typhoon. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- "Global Catastrophe Recap August 2017" (PDF). thoughtleadership.aonbenfield.com. Aon Benfield. Retrieved September 7, 2017.

- "Marine Weather Warning for GMDSS Metarea XI 2017-07-18T00:00:00Z". WIS Portal – GISC Tokyo. Japan Meteorological Agency. July 18, 2017. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- "RSMC TROPICAL CYCLONE BEST TRACK 1705 NORU". Japan Meteorological Agency. September 29, 2017. Archived from the original on September 29, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2017.

- "WTPQ20 RJTD 191200 RSMC Tropical Cyclone Advisory". Japan Meteorological Agency. July 19, 2017. Archived from the original on July 20, 2017. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- "Significant Tropical Weather Advisory for the Western and South Pacific Oceans Reissued/190000Z-190600Z Jul 2017". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. July 19, 2017. Archived from the original on July 20, 2017. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- "Tropical Cyclone Formation Alert". WIS Portal – GISC Tokyo. Joint Typhoon Warning Center. July 20, 2017. Archived from the original on August 4, 2017. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- "WTPQ20 RJTD 210000 RSMC Tropical Cyclone Advisory". Japan Meteorological Agency. July 21, 2017. Archived from the original on July 21, 2017. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Tropical Depression 07W (Seven) Warning Nr 001". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. July 20, 2017. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Tropical Storm 07W (Noru) Warning Nr 004". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. July 21, 2017. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Tropical Storm 07W (Noru) Warning Nr 005". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. July 21, 2017. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- "WTPQ20 RJTD 231200 RSMC Tropical Cyclone Advisory". Japan Meteorological Agency. July 23, 2017. Archived from the original on July 23, 2017. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- Kitamoto, Asanobu. "Typhoon List by Maximum Wind". Digital Typhoon. Retrieved October 6, 2017.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 07W (Noru) Warning Nr 11". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. July 23, 2017. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 07W (Noru) Warning Nr 15". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. July 24, 2017. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 07W (Noru) Warning Nr 16". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. July 24, 2017. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 07W (Noru) Warning Nr 17". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. July 24, 2017. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 07W (Noru) Warning Nr 19". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. July 25, 2017. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 07W (Noru) Warning Nr 22". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. July 26, 2017. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 07W (Noru) Warning Nr 25". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. July 26, 2017. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 07W (Noru) Warning Nr 26". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. July 27, 2017. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 07W (Noru) Warning Nr 29". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. July 27, 2017. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 07W (Noru) Warning Nr 30". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. July 28, 2017. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 07W (Noru) Warning Nr 34". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. July 29, 2017. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Tropical Storm 07W (Noru) Warning Nr 37". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. July 29, 2017. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 07W (Noru) Warning Nr 39". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. July 30, 2017. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Super Typhoon 07W (Noru) Warning Nr 41". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. July 30, 2017. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 07W (Noru) Warning Nr 44". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. July 31, 2017. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 07W (Noru) Warning Nr 46". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. August 1, 2017. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 07W (Noru) Warning Nr 49". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. August 1, 2017. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 07W (Noru) Warning Nr 52". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. August 2, 2017. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 07W (Noru) Warning Nr 54". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. August 3, 2017. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 07W (Noru) Warning Nr 59". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. August 4, 2017. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 07W (Noru) Warning Nr 60". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. August 4, 2017. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 07W (Noru) Warning Nr 63". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. August 5, 2017. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 07W (Noru) Warning Nr 65". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. August 5, 2017. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 07W (Noru) Warning Nr 67". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. August 6, 2017. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 07W (Noru) Warning Nr 68". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. August 6, 2017. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- Kitamoto, Asanobu. "台風201705号の全般台風情報一覧". Digital Typhoon (in Japanese). Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- "WTPQ20 RJTD 071500 RSMC Tropical Cyclone Advisory". Japan Meteorological Agency. August 7, 2017. Archived from the original on August 7, 2017. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Tropical Storm 07W (Noru) Warning Nr 72". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. August 7, 2017. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Tropical Depression 07W (Noru) Warning Nr 74". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. August 8, 2017. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- "Tropical Depression 07W (Noru) Warning Nr 076". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. August 8, 2017. Archived from the original on August 8, 2017. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- Martins, Daniel (August 7, 2017). "Deaths reported as weakening Noru slams Japan". The Weather Network. Retrieved September 12, 2017.

- "平成29年台風第5号による被害及び消防機関等の対応状況等について(第11報)" (PDF) (in Japanese). Fire and Disaster Management Agency. August 9, 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 11, 2017. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Typhoon Noru (2017). |

- JMA General Information of Typhoon Noru (1705) from Digital Typhoon

- JMA Best Track Data of Typhoon Noru (1705) (in Japanese)

- 07W.NORU from the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory