Tupi people

The Tupi people were one of the most numerous peoples indigenous to Brazil, before colonisation. Scholars believe that while they first settled in the Amazon rainforest, from about 2,900 years ago the Tupi started to migrate southward and gradually occupied the Atlantic coast of Southeast Brazil.[1]

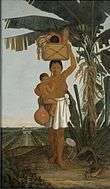

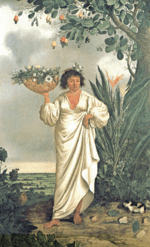

Albert Eckhout's painting of the Tupi | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 1,000,000 (historically), Potiguara 10,837, Tupinambá de Olivença 3,000, Tupiniquim 2,630, others extinct as tribes but blood ancestors to Pardo and Mestizo Brazilian population | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Central and Coastal Brazil | |

| Languages | |

| Tupi languages, later língua geral, much later Portuguese | |

| Religion | |

| Indigenous, later Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| The Kayapo and Guaraní tribes |

History

The Tupi people inhabited almost all of Brazil's coast when the Portuguese first arrived there. In 1500, their population was estimated at 1 million people, nearly equal to the population of Portugal at the time. They were divided into tribes, each tribe numbering from 300 to 2,000 people. Some examples of these tribes are: Tupiniquim, Tupinambá, Potiguara, Tabajara, Caetés, Temiminó, Tamoios. The Tupi were adept agriculturalists; they grew cassava, corn, sweet potatoes, beans, peanuts, tobacco, squash, cotton and many others. There was not a unified Tupi identity despite the fact that they spoke a common language.

European colonization

From the 16th century onward, the Tupi, like other natives from the region, were assimilated, enslaved, or killed by diseases such as smallpox[2] or by Portuguese settlers and Bandeirantes (colonial Brazil scouts), nearly leading to their complete annihilation, with the exception of a few isolated communities. The remnants of these tribes are today confined to indigenous territories or acculturated to some degree into the dominant society.[3]

Cannibalism

According to primary source accounts by primarily European writers, the Tupi were divided into several tribes which would constantly engage in war with each other. In these wars the Tupi would normally try to capture their enemies to later kill them in cannibalistic rituals.[3] The warriors captured from other Tupi tribes were eaten as it was believed by them that this would lead to their strength being absorbed and digested; thus, in fear of absorbing weakness, they chose only to sacrifice warriors perceived to be strong and brave. For the Tupi warriors, even when prisoners, it was a great honor to die valiantly during battle or to display courage during the festivities leading to the sacrifice.[4] The Tupi have also been documented to eat the remains of dead relatives as a form of honoring them.[5]

The practice of cannibalism among the Tupi was made famous in Europe by Hans Staden, a German soldier, mariner, and mercenary, traveling to Brazil to steal riches, who was captured by the Tupi in 1552. In his account published in 1557, he tells that the Tupi carried him to their village where it was claimed he was to be devoured at the next festivity. There, he allegedly won the friendship of a powerful chief, whom he cured of a disease, and his life was spared. [6]

Cannibalistic rituals among Tupi and other tribes in Brazil decreased steadily after European contact and religious intervention. When Cabeza de Vaca, a Spanish conquistador, arrived in Santa Catarina in 1541, for instance, he attempted to ban cannibalistic practices in the name of the King of Spain.[7]

Because our understanding of Tupi cannibalism relies solely on primary source accounts of primarily European writers, the very existence of cannibalism has been disputed by some in academic circles. William Arens seeks to discredit Staden's and other writers' accounts of cannibalism in his book The Man-Eating Myth: Anthropology & Anthropophagy, where he claims that when concerning the Tupinambá, "rather than dealing with an instance of serial documentation of cannibalism, we are more likely confronting only one source of dubious testimony which has been incorporated almost verbatim into the written reports of others claiming to be eyewitnesses".[8]

Race-mixing and Cunhadismo

Many indigenous peoples were important for the formation of the Brazilian people, but the main group was the Tupi. When the Portuguese explorers arrived in Brazil in the 16th century, the Tupi were the first Amerindian group to have contact with them. Soon, a process of mixing between Portuguese settlers and indigenous women started. The Portuguese colonists rarely brought women, making the Indian women the "breeding matrix of the Brazilian people".[3] When the first Europeans arrived, the phenomenon of "cunhadismo" (from Portuguese cunhado, "brother in law") began to spread by the colony. Cunhadismo was an old Indian tradition of incorporating strangers to their community. The Indians offered the Portuguese an Indian girl as wife. Once he agreed, he formed a bond of kinship with all the Indians of the tribe. Polygyny, a common practice among South American Indians, was quickly adopted by European settlers. This way, a single European man could have dozens of Indian wives (temericós).[3]

Cunhadismo was used as recruitment of labour. The Portuguese could have many temericós and thus a huge number of Indian relatives who were induced to work for him, especially to cut pau-brasil and take it to the ships on the coast. In the process, a large mixed-race (mameluco) population was formed, which in fact occupied Brazil. Without the practice of cunhadismo, the Portuguese colonization was impractical. The number of Portuguese men in Brazil was very small and Portuguese women were even fewer in number. The proliferation of mixed-race people in the wombs of Indian women provided for the occupation of the territory and the consolidation of the Portuguese presence in the region.[3]

Influence in Brazil

Although the Tupi population largely disappeared because of European diseases to which they had no resistance or because of slavery, a large population of maternal Tupi ancestry occupied much of Brazilian territory, taking the ancient traditions to several points of the country. Darcy Ribeiro wrote that the features of the first Brazilians were much more Tupi than Portuguese, and even the language that they spoke was a Tupi-based language, named Nheengatu or Língua Geral, a lingua franca in Brazil until the 18th century.[3] The region of São Paulo was the biggest in the proliferation of Mamelucos, who in the 17th century under the name of Bandeirantes, spread throughout the Brazilian territory, from the Amazon rainforest to the extreme South. They were responsible for the major expansion of the Iberian culture in the interior of Brazil. They acculturated the Indian tribes who lived in isolation, and took the language of the colonizer, which was not Portuguese yet, but Nheengatu itself, to the most inhospitable corners of the colony. Nheengatu is still spoken in certain regions of the Amazon, although the Tupi-speaking Indians did not live there. The Nheengatu language, as in other regions of the country, was introduced there by Bandeirantes from São Paulo in the 17th century. The way of life of the Old Paulistas could almost be confused with the Indians. Within the family, only Nheengatu was spoken. Agriculture, hunting, fishing and gathering of fruits were also based on Indian traditions. What differentiated the Old Paulistas from the Tupi was the use of clothes, salt, metal tools, weapons and other European items.[3]

When these areas of large Tupi influence started to be integrated into the market economy, Brazilian society gradually started to lose its Tupi characteristics. The Portuguese language became dominant and Língua Geral virtually disappeared. The rustic Indian techniques of production were replaced by European ones, in order to elevate the capacity of exportation.[3] Brazilian Portuguese absorbed many words from Tupi. Some examples of Portuguese words that came from Tupi are: mingau, mirim, soco, cutucar, tiquinho, perereca, tatu. The names of several local fauna – such as arara ("macaw"), jacaré ("South American alligator"), tucano ("toucan") – and flora – e.g. mandioca ("manioc") and abacaxi ("pineapple") – are also derived from the Tupi language. A number of places and cities in modern Brazil are named in Tupi (Itaquaquecetuba, Pindamonhangaba, Caruaru, Ipanema). Anthroponyms include Ubirajara, Ubiratã, Moema, Jussara, Jurema, Janaína.[9] Tupi surnames do exist, but they do not imply any real Tupi ancestry; rather they were adopted as a manner to display Brazilian nationalism.[10]

The Tupinambá tribe is fictitiously portrayed in Nelson Pereira dos Santos' satirical 1971 film How Tasty Was My Little Frenchman (Como Era Gostoso o Meu Francês). Its name is also adapted by science: Tupinambis is a genus of tegus, arguably the best-known lizards of Brazil.

The large offshore Tupi oil field discovered off the coast of Brazil in 2006 was named in honor of the Tupi people.

The Guaraní are a different native group which inhabits southern Brazil, Uruguay, Paraguay and northern Argentina and speaks the distinct Guaraní languages, but these are in the same language family as Tupi.

Notable Tupi people

- Catarina Paraguaçu, 1528—1586

- Araribóia, founder of Niterói, Brazil

See also

- De Gestis Meni de Saa

- Guaraní War

- José de Anchieta

- Língua Geral

- Manuel da Nóbrega

- Tupian languages

References

- "Saída dos tupi-guaranis da Amazônia pode ter ocorrido há 2.900 anos". Archived from the original on 2011-10-07.

- "Unnatural Histories - Amazon". BBC Four.

- Darcy Ribeiro – O Povo Brasileiro, Vol. 07, 1997 (1997), pp. 28 to 33; 72 to 75 and 95 to 101."

- "Um alemão na Terra dos Canibais - Revista de História".

- Agnolin, Adone. O apetite da antropologia. São Paulo, Associação Editorial Humanitas, 2005. p. 285.

- Staden, Hans. Duas viagens ao Brasil: primeiros registros sobre o Brasil. Porto Alegre: L&PM, 2011, p. 51-52

- "Museu de Arte e Origens".

- (New York : Oxford University Press, 1979; ISBN 0-19-502793-0)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-04-27. Retrieved 2009-06-10.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Sérgio Cabral (1 January 1997). Antônio Carlos Jobim: uma biografia. Lumiar Editora. p. 39. ISBN 978-85-85426-42-2.