Schoenoplectus acutus

Schoenoplectus acutus (syn. Scirpus acutus, Schoenoplectus lacustris, Scirpus lacustris subsp. acutus), called tule /ˈtuːliː/, common tule, hardstem tule, tule rush, hardstem bulrush, or viscid bulrush, is a giant species of sedge in the plant family Cyperaceae, native to freshwater marshes all over North America.[1] The common name derives from the Nāhuatl word tōllin [ˈtoːlːin], and was first applied by the early settlers from New Spain who recognized the marsh plants in the Central Valley of California as similar to those in the marshes around Mexico City.

| Schoenoplectus acutus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Schoenoplectus acutus var. occidentalis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Clade: | Commelinids |

| Order: | Poales |

| Family: | Cyperaceae |

| Genus: | Schoenoplectus |

| Species: | S. acutus |

| Binomial name | |

| Schoenoplectus acutus | |

Tules once lined the shores of Tulare Lake, California, formerly the largest freshwater lake in the western United States. It was drained by land speculators in the 20th century. The expression "out in the tules" is still common, deriving from the dialect of old Californian families and means "where no one would want to live", with a touch of irony. The phrase is comparable to "out in the boondocks".[2]

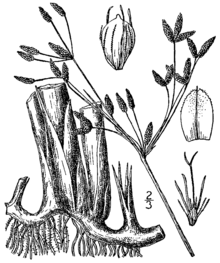

Schoenoplectus acutus has a thick, rounded green stem growing to 1 to 3 m (3 to 10 ft) tall, with long, grasslike leaves, and radially symmetrical, clustered, pale brownish flowers. Tules at shorelines play an important ecological role, helping to buffer against wind and water forces, thereby allowing the establishment of other types of plants and reducing erosion. Tules are sometimes cleared from waterways using herbicides. When erosion occurs, tule rhizomes are replanted in strategic areas.

The two varieties are:

- Schoenoplectus acutus var. acutus – northern and eastern North America

- Schoenoplectus acutus var. occidentalis – southwestern North America

History and culture

Dyed and woven, tules are used to make baskets, bowls, mats, hats, clothing, duck decoys, and even boats by Native American groups. Before the Salish got horses for bison hunting, they lived in tents covered with sewed mats of tule.[3] At least two tribes, the Wanapum and the Pomo people, constructed tule houses as recently as the 1950s and still do for special occasions. Bay Miwok, Coast Miwok, and Ohlone peoples used the tule in the manufacture of canoes or balsas, for transportation across the San Francisco Bay and using the marine and wetland resources.[4] Northern groups of Chumash used the tule in the manufacture of canoes rather than the sewn-plank tomol usually used by Chumash and used them to gather marine harvests.[5]

The Paiutes named a neighboring tribe the Si-Te-Cah in their language, meaning tule eaters. The young sprouts and shoots can be eaten raw and the rhizomes and unripe flower heads can be boiled as vegetables.

One of the few Pomo survivors of the Bloody Island Massacre (also called the Clear Lake Massacre) in Northern California, a 6-year-old girl named Ni'ka, or Lucy Moore, evaded the United States Cavalry by hiding behind the tule reeds in the bloodied water.[6] Her descendants have since formed the Lucy Moore Foundation to work for better relations between the Pomo and residents of California.

It is so common in wetlands in California, several places in the state were named for it, including Tulare (a tulare is a tule marsh). Tule Lake is near the Oregon border and includes Tule Lake National Wildlife Refuge. It was the site of an internment camp for Japanese Americans during World War II, imprisoning 18,700 people at its peak. The town of Tulelake is northeast of the lake. California also has a Tule River. The Tule Desert is located in Arizona and Nevada. Nevada also has Tule Springs.

California's dense, ground-hugging tule fog is named for the plant, as are the tule elk and tule perch. The giant garter snake (Thamnophis gigas) was historically closely associated with tule marshes in California's Central Valley.

Notes

- P.A. Munz, 1973

- "Out in the Tules: The Freshwater Marsh of Coyote Hills", by Joe Eaton, in Bay Nature, Jan-Mar 2004

- Teit, James A. (1930): The Salishan Tribes of the Western Plateaus. Smithsonian Institution. 45th Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology. Washington, p. 332.

- Klar & Jones, 2007

- C.M. Hogan, 2008

- https://newsmaven.io/indiancountrytoday/archive/pomo-indians-remember-1850-bloody-island-massacre-with-events-may-18-19-tlH7xF2Nq0SbN3K596ndfg/

References

- Munz, Philip A. A California Flora. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1973, copyright 1959

- Munz, Philip A. A California Flora: Supplement. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1976 (p. 183 Scirpus lacutris, validus, glaucus.)

- Jones, Terry L. and Klar, Kathryn California prehistory: colonization, culture, and complexity, Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira Press, 2007

- C.Michael Hogan (2008) Morro Creek, published by Megalithic Portal, ed. Andy Burnham

Further reading

- Swall, Corinne; Nuyens III, Louis (2003). Tule reed boat workbook : a voyage of adventure. Kentfield, CA: Mother Lode Musical Theatre, Watershed Preservation Network. Archived from the original on 2011-07-27.

External links

- Tule Boat Photo Gallery

- Tule reed canoe, Ohlone, launched on Lake Merced, San Francisco

- Tule reed canoe, Modoc