Tsurugaoka Hachimangū

Tsurugaoka Hachimangū (鶴岡八幡宮) is the most important Shinto shrine in the city of Kamakura, Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan. The shrine is at the geographical and cultural center of the city of Kamakura, which has largely grown around it and its 1.8 km approach. It is the venue of many of its most important festivals, and hosts two museums.

| Tsurugaoka Hachimangū 鶴岡八幡宮 | |

|---|---|

The approach to the Senior Shrine (hongū). | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Shinto |

| Deity | Hachiman |

| Type | Hachiman Shrine |

| Location | |

| Location | 2-1-31 Yukinoshita, Kamakura, Kanagawa |

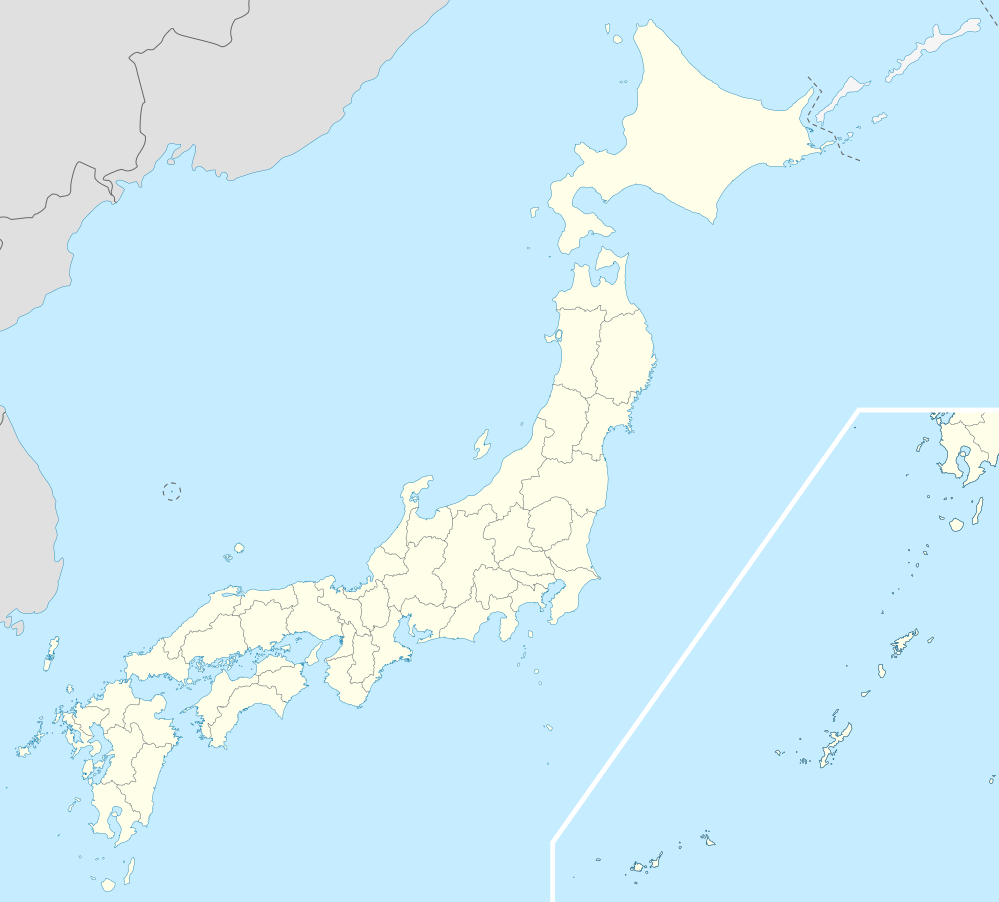

Shown within Japan | |

| Geographic coordinates | 35°19′29″N 139°33′21″E |

| Architecture | |

| Date established | 1063 |

| Website | |

| www | |

| Tsurugaoka Hachimangū | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japanese name | |||||

| Kanji | 鶴岡八幡宮 | ||||

| Hiragana | つるがおかはちまんぐう | ||||

| |||||

Tsurugaoka Hachimangū was for most of its history not only a Hachiman shrine, but also a Tendai Buddhist temple, a fact which explains its general layout, typical of Japanese Buddhist architecture.[1]

At the left of its great stone stairway stood a 1000-year-old ginkgo tree, which was uprooted by a storm in the early hours of March 10, 2010. The shrine is an Important Cultural Property.

History

This shrine was originally built in 1063 as a branch of Iwashimizu Shrine in Zaimokuza where tiny Moto Hachiman now stands and dedicated to the Emperor Ōjin, (deified with the name Hachiman, tutelary kami of warriors), his mother Empress Jingu and his wife Hime-gami. Minamoto no Yoritomo, the founder of the Kamakura shogunate, moved it to its present location in 1191 and invited Hachiman[note 1] to reside in the new location to protect his government.[1]

Assassination of Minamoto no Sanetomo

One of the historical events the shrine is tied to is the assassination of Sanetomo, last of Minamoto no Yoritomo's sons.

Under heavy snow on the evening of February 12, 1219 (Jōkyū 1, 26th day of the 1st month),[note 2] shōgun Minamoto no Sanetomo was coming down from Tsurugaoka Hachimangū's Senior Shrine after assisting to a ceremony celebrating his nomination to Udaijin.[2] His nephew Kugyō, son of second shōgun Minamoto no Yoriie, came out from next to the stone stairway of the shrine, then suddenly attacked and assassinated him in the hope to become shōgun himself.[2] The killer is often described as hiding behind the giant ginkgo, but no contemporary text mentions the tree, and this detail is likely an Edo-period invention first appeared in Tokugawa Mitsukuni's Shinpen Kamakurashi. For his act Kugyō was himself beheaded a few hours later,[2] thus bringing the Seiwa Genji line of the Minamoto clan and their rule in Kamakura to a sudden end.

Shrine and temple

Tsurugaoka Hachimangū is now just a Shinto shrine but, for the almost 700 years from its foundation until the Shinto and Buddhism Separation Order (神仏判然令) of 1868, its name was Tsurugaoka Hachimangū-ji (鶴岡八幡宮寺) and it was also a Buddhist temple, one of the oldest in Kamakura.[3] The mixing of Buddhism and kami worship in shrine-temple complexes like Tsurugaoka called jingū-ji had been normal for centuries until the Meiji government decided, for political reasons, that this was to change.[4] (According to the honji suijaku theory, Japanese kami were just local manifestations of universal buddhas, and Hachiman in particular was one of the earliest and most popular syncretic gods. Already in the 7th century, for example in Usa, Kyūshū, Hachiman was worshiped together with Miroku Bosatsu (Maitreya).[5])

The separation policy (shinbutsu bunri) was the direct cause of serious damage to important cultural assets. Because mixing the two religions was now forbidden, shrines and temples had to give away some of their treasures, thus damaging the integrity of their cultural heritage and decreasing the historical and economic value of their properties.[3] Tsurugaoka Hachiman's giant Niō (仁王)] (the two wooden wardens usually found at the sides of a temple's entrance), being objects of Buddhist worship and therefore illegal where they were, had to be sold to Jufuku-ji, where they still are.[note 3][6] The shrine also had to destroy Buddhism-related buildings, for example its shichidō garan (七堂伽藍) (a complete seven-building Buddhist temple compound), its tahōtō tower, and its midō (御堂, enshrinement hall (of a buddha)).[3]

In important ways, Tsurugaoka Hachimangū was impoverished in 1868 as a consequence of this Meiji era policy. The imposed, inflexible reform orthodoxy of this early Meiji period was unquestionably intended to affect Buddhism and Shinto. However, the structures and artwork of this ancient shrine-temple were not yet construed as important elements of Japan's cultural patrimony.[note 4] What remains to be visited today is only a partial version of the original shrine-temple.

Meiji-Showa periods

From 1871 through 1946, Tsurugaoka was officially designated one of the Kokuhei Chūsha (国幣中社), meaning that it stood in the mid-range of ranked, nationally significant shrines.

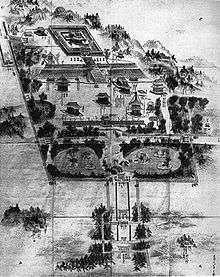

Layout of shrine complex

Both the shrine and the city were built with Feng Shui in mind.[7] The present location was carefully chosen as the most propitious after consulting a diviner because it had a mountain to the north (the Hokuzan (北山)), a river to the east (the Namerikawa), a great road to the west (the Kotō Kaidō (古東街道)) and was open to the south (on Sagami Bay).[7] Each direction was protected by a god: Genbu guarded the north, Seiryū the east, Byakko the west and Suzaku the south.[7] The willows near the Genpei Ponds (see below) and the catalpas next to the Museum of Modern Art represent respectively Seiryū and Byakko.[7] In spite of all the changes the shrine has gone through over the years, in this respect Yoritomo's design is still basically intact.[7]

As one enters, after the first torii (Shinto gate) there are three small bridges, two flat ones on the sides and an arched one at the center. In the days of the shogunate there used to be only two, a normal one and another arched, made in wood and painted red.[1] The shōgun would leave his retinue there and proceed alone on foot to the shrine.[1] The arched bridge was called Akabashi (Red Bridge), and was reserved to him: common people had to use the flat one.[1] The bridges span over a canal that joins together two ponds popularly called Genpei-ike (源平池), or "Genpei ponds".[8] The term comes from the names of the two families, the Minamoto ("Gen") and the Taira ("Pei"), that fought each other in Yoritomo's day.[8]

The stele just after and to the left of the first torii explains the origin of the name:[note 5]

The Genpei Ponds

The Azuma Kagami says that "In April 1182 Minamoto no Yoritomo told monk Senkō and Ōba Kageyoshi to have two ponds dug within the shrine." According to another version of the story, it was Yoritomo's wife Masako who, to pray for the prosperity of the Minamoto family, had these ponds dug, and had white lotuses planted in the east one and red ones in the west one, colors which are those of the Taira and Minamoto clans. From this derives their name.

The red of those lotuses is supposed to stand for the spilled blood of the Taira.[8]

Sub-shrines and infrastructures

Tsurugaoka Hachimangū includes several sub-shrines, the most important of which are the Junior Shrine (Wakamiya (若宮)) at the bottom, and the Senior Shrine (Hongū (本宮)) 61 steps above.[8] The present Senior Shrine building was constructed in 1828 by Tokugawa Ienari, the 11th Tokugawa shōgun in the Hachiman-zukuri style.[9] Right under the stairway there's an open pavilion called Maiden (舞殿) where weddings, dances and music are performed.[8] A couple of hundred meters to the right of the Junior Shrine lies Shirahata Jinja (白旗神社), a National Treasure.[8] To the left of the Senior Shrine lies Maruyama Inari Shrine (丸山稲荷社) with its many torii.[8]

Near Shirahata Jinja one can also find the Yui Wakamiya Yōhaijo (由比若宮遥拝所), literally the "Yui Wakamiya Pray-at-a-Distance Place" (see photo). This facility, originally created for the shōgun's benefit, allows one to worship at distant Yui Wakamiya (Moto Hachiman) without actually going all the way to Zaimokuza.[8][10]

Right next to the Yui Wakamiya Yōhaijo there are two stones: pouring water on them should reveal on each the contour of a turtle. One of the islands in the Minamoto pond hosts a sub-shrine called Hataage Benzaiten Shrine (旗上弁財天社) dedicated to goddess Benzaiten, a Buddhist deity. For this reason, the sub-shrine was dismantled in 1868 at the time of the "Shinto and Buddhism separation" order (see below) and rebuilt in 1956.[8]

Wakamiya Ōji

An unusual feature of the shrine is its 1.8 km sandō (参道) (approach), which extends all the way to the ocean in Yuigahama and doubles as Wakamiya Ōji Avenue, Kamakura's main street. Built by Minamoto no Yoritomo as an imitation of Kyoto's Suzaku Ōji (朱雀大路), Wakamiya Ōji used to be much wider and flanked by both a 3 m deep canal and pine trees (see Edo period print below).[11]

Walking from the beach toward the shrine one passes through three torii, or Shinto gates, called respectively Ichi no Torii (first gate), Ni no Torii (second gate) and San no Torii (third gate). Between the first and the second lies Geba Yotsukado (下馬四つ角) which, as the name indicates, was the place where riders had to get off their horses in deference to Hachiman and his shrine.[11]

Some hundred meters further, between the second and third torii, begins the dankazura (段葛), a raised pathway flanked by cherry trees. The dankazura becomes gradually wider so that, seen from the shrine, it will look longer than it really is.[11] The entire length of the dankazura is under the direct administration of the shrine.

Giant ginkgo

The ginkgo tree that stood next to Tsurugaoka Hachimangū's stairway almost from its foundation and which appears in almost every old print of the shrine was completely uprooted and greatly damaged at 4:40 in the morning on March 10, 2010. According to an expert who analyzed the tree, the fall is likely due to rot. Both the tree's stump and a section of its trunk replanted nearby have produced leaves (see photo).

The tree was nicknamed kakure-ichō (隠れ銀杏, hiding ginkgo) because according to an Edo period urban legend, a now-famous assassin hid behind it before striking his victim. For details, see the article Shinpen Kamakurashi.

![]()

Activities

Tsurugaoka Hachimangū is the center of much cultural activity and both yabusame, (archery from horseback), and kyūdō (Japanese archery) are practiced within the shrine.[8] It also has extensive peony gardens, three coffee shops, a kindergarten, offices and a dōjō. Within its grounds stand two museums, the Kamakura Museum of National Treasures, owned by the City of Kamakura, and the prefectural Museum of Modern Art.

Gallery of Shrines at Tsurugaoka Hachimangū

Tsurugaoka Hachimangū - a Shinto shrine with Buddhist architecture

Tsurugaoka Hachimangū - a Shinto shrine with Buddhist architecture- The inner court of Tsurugaoka Hachimangū

- The red torii (gates) along the road to Inari shrine

- Shirahata Shrine

- Hataage Benzaiten Shrine

- The two stones at Yui Wakamiya Yōhaijo

Notes

- A kami is transferred to a new location through a process called kanjō.

- Gregorian date obtained directly from the original Nengō using Nengocalc Archived 2007-09-30 at the Wayback Machine

- See article Jufuku-ji

- After 1897 when the Law for the Preservation of Ancient Shrines and Temples was enacted, a range of other factors would come to be considered.

- Original Japanese text available here

See also

- Azuma Kagami

- Kamakura Museum of National Treasures

- List of National Treasures of Japan (crafts-others)

- List of National Treasures of Japan (crafts-swords)

References

- Mutsu (1995/06: 102-104)

- Azuma Kagami; Mutsu (1995/06: 102–104)

- Kamakura Shōkō Kaigijo (2008: 28)

- Encyclopedia of Shinto - Shinbutsu Bunri accessed on June 7, 2008 (in English)

- Bernhard Scheid

- Mutsu (1995/06:174)

- Ōnuki (2008:80)

- Kamiya (2008: 17 - 23)

- Bocking, Brian (1997). A Popular Dictionary of Shinto - 'Hachiman-zukuri'. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7007-1051-5.

- Komachi, Nishi Mikado, by the Kamakura Citizen's Network, retrieved on July 23, 2008

- Kamakura Shōkō Kaigijo (2008: 56-57)

Bibliography

- Azuma Kagami, accessed on September 4, 2008; National Archives of Japan 特103-0001, digitized image of the Azumakagami (in Japanese)

- Brinkley, Frank and Dairoku Kikuchi. (1915). A History of the Japanese People from the Earliest Times to the End of the Meiji Era. New York: Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Kamakura Shōkō Kaigijo (2008). Kamakura Kankō Bunka Kentei Kōshiki Tekisutobukku (in Japanese). Kamakura: Kamakura Shunshūsha. ISBN 978-4-7740-0386-3.

- Kamiya, Michinori (August 2000). Fukaku Aruku - Kamakura Shiseki Sansaku Vol. 1 (in Japanese). Kamakura: Kamakura Shunshūsha. ISBN 4-7740-0340-9.

- Mass, Jeffrey P. (1995). Court and Bakufu in Japan: Essays in Kamakura History. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2473-9

- Mutsu, Iso (June 1995). Kamakura. Fact and Legend. Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 0-8048-1968-8.

- Ōnuki, Akihiko (2008). Kamakura. Rekishi to Fushigi wo Aruku (in Japanese). Tokyo: Jitsugyō no Nihonsha. ISBN 978-4-408-59306-7.

- Ponsonby-Fane, Richard Arthur Brabazon. (1962). Sovereign and Subject. Kyoto: Ponsonby Memorial Society.

- Scheid, Bernhard (2008-04-16). "Honji suijaku: Die Angleichung von Buddhas und Kami" (in German). University of Vienna. Retrieved 2008-11-04.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- Official website (in Japanese)

- National Archives of Japan, Digital Gallery:

- Mori Koan map: Soshu Kamakuranozu, drawn in 5th year of Horeki (1755).

- New York Public Library Digital Gallery:

- NYPL ID 119488, unknown photographer, albumen print, 189?-190?: Perspective beyond torii

- NYPL ID 118907, Felice Beato, albumen print, 187?: Shrine steps and forecourt

- NYPL ID 110031, Kusakabe Kimbei, albumen print, 188?-189? Great stairway

- NYPL ID 118911, Felice Beato, albumen print, 187?: Senior Shrine structural detail

- NYPL ID 118912, Felice Beato, albumen print, 187?: Tahōtō, single-storied pagoda

- 428219205 Tsurugaoka Hachimangū on OpenStreetMap