Harlequin

Harlequin (/ˈhɑːrləkwɪn/; Italian: Arlecchino [arlekˈkiːno]) is the best-known of the zanni or comic servant characters from the Italian commedia dell'arte. The role is traditionally believed to have been introduced by Zan Ganassa in the late 16th century,[2] was definitively popularized by the Italian actor Tristano Martinelli in Paris in 1584–1585,[3] and became a stock character after Martinelli's death in 1630.

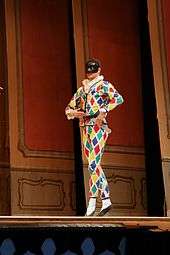

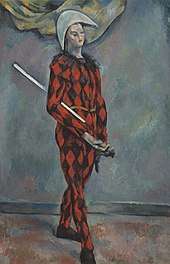

The Harlequin is characterized by his chequered costume. His role is that of a light-hearted, nimble, and astute servant, often acting to thwart the plans of his master, and pursuing his own love interest, Columbina, with wit and resourcefulness, often competing with the sterner and melancholic Pierrot. He later develops into a prototype of the romantic hero. Harlequin inherits his physical agility and his trickster qualities, as well as his name, from a mischievous "devil" character in medieval passion plays.

The Harlequin character first appeared in England early in the 17th century and took centre stage in the derived genre of the Harlequinade, developed in the early 18th century by John Rich.[4] As the Harlequinade portion of English dramatic genre pantomime developed, Harlequin was routinely paired with the character Clown. As developed by Joseph Grimaldi around 1800, Clown became the mischievous and brutish foil for the more sophisticated Harlequin, who became more of a romantic character. The most influential such in Victorian England were William Payne and his sons the Payne Brothers, the latter active during the 1860s and 1870s.

Origin of the name

The name Harlequin is taken from that of a mischievous "devil" or "demon" character in popular French passion plays. It originates with an Old French term herlequin, hellequin, first attested in the 11th century, by the chronicler Orderic Vitalis, who recounts a story of a monk who was pursued by a troop of demons when wandering on the coast of Normandy (France ) at night.[5][6] These demons were led by a masked, club-wielding giant and they were known as familia herlequin (var. familia herlethingi). This medieval French version of the Germanic Wild Hunt, Mesnée d'Hellequin, has been connected to the English figure of Herla cyning ("host-king"; German Erlkönig).[7] Hellequin was depicted as a black-faced emissary of the devil, roaming the countryside with a group of demons chasing the damned souls of evil people to Hell. The physical appearance of Hellequin offers an explanation for the traditional colours of Harlequin's red-and-black mask.[8][9] The name's origin could also be traced to a knight from the 9th century, Hellequin of Boulogne, who died fighting the Normans and originated a legend of devils.[10] In Cantos XXI and XXII from Dante's Inferno there is a devil by the name of Alichino.[5][11] The similarities between the devil in Dante's Inferno and the Arlecchino are more than cosmetic and that the prank like antics of the devils in the aforementioned antics reflect some carnivalesque aspects.[11]

The first known appearance on stage of Hellequin is dated to 1262, the character of a masked and hooded devil in Jeu da la Feuillière by Adam de la Halle, and it became a stock character in French passion plays.[12]

History

The re-interpretation of the "devil" stock character as a zanni character of the commedia dell'arte took place in the 16th century in France.[15] Zan Ganassa, whose troupe is first mentioned in Mantua in the late 1560s, is one of the earliest known actors suggested to have performed the part,[4] although there is "little hard evidence to support [it]."[16] Ganassa performed in France in 1571, and if he did play the part there, he left the field open for another actor to take up the role, when he took his troupe to Spain permanently in 1574.[17]

Among the earliest depictions of the character are a Flemish painting (c. 1571-1572) in the Museum of Bayeux[13][14] and several woodblock prints probably dating from the 1580s in the Fossard collection, discovered by Agne Beijer in the 1920s among uncatalogued items in the Nationalmuseum Stockholm.[18]

_-_Gallica_2010_(adjusted).jpg)

Tristano Martinelli is the first actor definitely known to have used the name 'Harlequin' (or 'Arlequin') from French folklore and adapted it for the comic secondo zanni role, and he probably first performed the part in France in (or just before) 1584 and only later did he bring the character to Italy, where he became known as Arlecchino.[19] The motley costume is sometimes attributed to Martinelli, who wore a linen costume of colourful patches, and a hare-tail on his cap to indicate cowardice. Martinelli's Harlequin also had a black leather half-mask, a moustache and a pointed beard. He was very successful, even playing at court and becoming a favourite of Henry IV of France, to whom he addressed insolent monologues (Compositions de Rhetorique de Mr. Don Arlequin, 1601).[20] Martinelli's great success contributed to the perpetuation of his interpretation of the zanni role, along with the name of his character, after his death in 1630, among others, by Nicolò Zecca, active c. 1630 in Bologna as well as Turin and Mantua.[21]

The character was also performed in Paris at the Comédie-Italienne in Italian by Giovan Battista Andreini and Angelo Costantini (c. 1654–1729) and in French as Arlequin in the 1660s by Dominique Biancolelli (1636–1688), who combined the zanni types, "making his Arlecchino witty, neat, and fluent in a croaking voice, which became as traditional as the squawk of Punch."[4] The Italians were expelled from France in 1697 for satirizing King Louis XIV's second wife, Madame de Maintenon,[22] but returned in 1716 (after his death), when Tommaso Antonio Vicentini ("Thomassin", 1682–1739) became famous in the part.[23] The rhombus shape of the patches arose by adaptation to the Paris fashion of the 17th century by Biancolelli.

Characteristics and dramatic function

Physicality

The primary aspect of Arlecchino was his physical agility.[5][8][24] He was very nimble and performed the sort of acrobatics the audience expected to see. The character would never perform a simple action when the addition of a cartwheel, somersault, or flip would spice up the movement.[10]

By contrast with the 'first zanni' Harlequin takes little or no part in the development of the plot. he has the more arduous task of maintaining the even rhythm of the comedy as a whole. He is therefore always on the go, very agile and more acrobatic than any of the other Masks.

— Oreglia, Giacomo[25]

Early characteristics of Arlecchino paint the character as a second zanni servant from northern Italy with the paradoxical attributes of a dimwitted fool and an intelligent trickster.[5][11] Arlecchino is sometimes referred to as putting on a show of stupidity in a metatheatrical attempt to create chaos within the play.[11] Physically, Arlecchino is described as wearing a costume covered in irregular patches, a hat outfitted with either a rabbit or fox's tail, and a red and black mask.[5] The mask itself is identified by carbuncles on the forehead, small eyes, a snub nose, hollow cheeks, and sometimes bushy brows with facial hair.[5] Arlecchino is often depicted as having a wooden sword hanging from a leather belt on his person.[5]

Aside from his acrobatics, Arlecchino is also known for having several specific traits such as:

- Appearing humpbacked without artificial padding

- The ability to eat large amounts of food quickly

- Using his wooden sword like a fan

- A parody of bel canto

and several other techniques.[5]

Speech

One of the major distinctions of commedia dell'arte is the use of regional dialects.[11] Arlecchino's speech evolved with the character. Originally speaking in a Bergamo dialect, the character adopted a mixture of French and Italian dialects when the character became more of a fixture in France so as to help the performers connect to the common masses.[5][11]

Dramatic function

Various troupes and actors would alter his behaviour to suit style, personal preferences, or even the particular scenario being performed. He is typically cast as the servant of an innamorato or vecchio much to the detriment of the plans of his master. Arlecchino often had a love interest in the person of Columbina, or in older plays any of the Soubrette roles, and his lust for her was only superseded by his desire for food and fear of his master. Occasionally, Arlecchino would pursue the innamorata, though rarely with success, as in the Recueil Fossard of the 16th century where he is shown trying to woo Donna Lucia for himself by masquerading as a foreign nobleman. He also is known to try to win any given lady for himself if he chances upon anyone else trying to woo her, by interrupting or ridiculing the new competitor. His sexual appetite is essentially immediate, and can be applied to any passing woman.[26]

Between the 16th and 17th centuries Arlecchino gained some function as a politically aware character. In the Comèdie itlaienne Arlecchino would parodie French tragedies as well comment on current events.[5]

Variants

Duchartre lists the following as variations on the Harlequin role:

Trivelino or Trivelin. Name is said to mean "Tatterdemalion." One of the oldest versions of Harlequin, dating to the 15th century. Costume almost identical to Harlequin's, but had a variation of the 17th century where the triangular patches were replaced with moons, stars, circles and triangles. In 18th century France, Trivelino was a distinct character from Harlequin. They appeared together in a number of comedies by Pierre de Marivaux including L'Île des esclaves.[27]

Truffa, Truffaldin or Truffaldino. Popular characters with Gozzi and Goldoni, but said to be best when used for improvisations. By the 18th century was a Bergamask caricature.[27]

Guazzetto. In the seventeenth century, a variety of anonymous engravings show Guazzetto rollicking, similar to Arlecchino. He wears a fox's brush, a large three-tiered collarette, wide breeches, and a loose jacket tied tightly by a belt. He also dons a neckerchief dropped over the shoulders like a small cape. Guazzetto's mask is characterized with a hooked nose and a mustache. His bat is shaped like a scimitar-esque sword.[27][28]

Zaccagnino. Character dating to the 15th century.

Bagatino. A juggler.

Pedrolino or Pierotto. A servant or valet clad in mostly white, created by Giovanni Pellesini.[27]

Famous Harlequins

16th century[25]

- Alberto Naselli (Zan Ganassa)

17th century[30]

- Tristano Martinelli

- Domenico Biancolelli

- Evaristo Gherardi

18th century[30]

- Pier Francesco Biancolelli

- Tommaso Visentini

- Carlo Bertinazzi

19th century

20th century[30]

- Marcello Moretti

English harlequinade and pantomime

The Harlequin character came to England early in the 17th century and took center stage in the derived genre of the Harlequinade, developed in the early 18th century by the Lincoln's Fields Theatre's actor-manager John Rich, who played the role under the name of Lun.[4] As the Harlequinade portion of English pantomime developed, Harlequin was routinely paired with the character Clown.

Two developments in 1800, both involving Joseph Grimaldi, greatly changed the pantomime characters.[31] Grimaldi starred as Clown in Charles Dibdin's 1800 pantomime, Peter Wilkins: or Harlequin in the Flying World at Sadler's Wells Theatre.[32][33] For this elaborate production, Dibdin introduced new costume designs. Clown's costume was "garishly colourful ... patterned with large diamonds and circles, and fringed with tassels and ruffs," instead of the tatty servant's outfit that had been used for a century. The production was a hit, and the new costume design was copied by others in London.[33] Later the same year, at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, in Harlequin Amulet; or, The Magick of Mona. Harlequin was modified to become "romantic and mercurial, instead of mischievous", leaving Grimaldi's mischievous and brutish Clown as the "undisputed agent" of chaos, and the foil for the more sophisticated Harlequin, who retained stylized dance poses.[34] The most influential such pair in Victorian England were the Payne Brothers, active during the 1860s and 1870s, who contributed to 20th-century "slapstick" comedy.

See also

Notes

- Alexandre Manceau, engraver. Sand 1860, after p. 80.

- Duchartre 1929, p. 82; Laurence Senelick in Banham 1995, "Harlequin" p. 472; Rudlin & Crick 2001, pp. 12–13.

- Andrews 2008, p. liv, note 32, citing Ferrone, Henke, and Gambelli.

- Laurence Senelick in Banham 1995, "Harlequin" p. 472.

- Oreglia 1968, pp. 56–70.

- Ecclesiastical History Book VIII Chapter 17

- Martin Rühlemann, Etymologie des wortes harlequin und verwandter wörter (1912). See also Normand R. Cartier, Le Bossu désenchanté: Étude sur le Jeu da la Feuillée, Librairie Droz, 1971, p. 132.

- Grantham, B., Playing Commedia, A Training Guide to Commedia Techniques, (Nick Hern Books) London, 2000

- Jean-Claude Schmitt (1999). Ghosts in the Middle Ages: The Living and the Dead in Medieval Society. University Of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-73888-8.

- Oreglia 1968, p. 56.

- Scuderi, Antonio (2000). "Arlecchino Revisited: Tracing the Demon from the Carnival to Kramer and Mr. Bean". Theatre History Studies. 20: 143–155.

- Lea 1934, p. 75.

- Sterling 1943, p. 20; Duchartre 1929, p. 84.

- Katritzky 2006, pp. 140–143, confirms that the dating of the painting is generally accepted; p. 236: "...this figure is still widely accepted as a depiction of Harlequin or Zan Ganassa, although often with reservations."

- Rudlin 1994, p. 76.

- Rudlin & Crick 2001, p. 12.

- Rudlin & Crick 2001, pp. 7–13. These authors speculate that Ganassa may have dropped the role in Spain, since apparently he gained too much weight to perform the required acrobatics.

- Katritzky 2006, pp. 107–108; Beijer & Duchartre 1928.

- Lea 1934, pp. 79–84; Katritzky 2006, pp. 102–104; Andrews 2008, pp. xxvi–xxvii.

- Maurice Charney (ed.), Comedy: A Geographic and Historical Guide, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2005, p. 239.

- Boni, Filippo de' (1852). Biografia degli artisti ovvero dizionario della vita e delle opere dei pittori, degli scultori, degli intagliatori, dei tipografi e dei musici di ogni nazione che fiorirono da'tempi più remoti sino á nostri giorni. Seconda Edizione. Venice; Googlebooks: Presso Andrea Santini e Figlio. p. p. 1103.

- Donald Roy in Banham 1995, "Comédie-Italienne" pp. 233–234.

- Laurence Senelick in Banham 1995, "Vicentini" p. 867.

- Rudlin 1994, p. 78.

- Oreglia 1968, p. 58.

- Rudlin 1994, p. 79.

- Oreglia 1968, p. 65.

- Duchartre 1929, pp. 159–160.

- Oreglia 1968, p. 139.

- Oreglia 1968, p. 59.

- Mayer III, David (1969). Harlequin in His Element. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 3.

- Neville, pp. 6–7

- McConnell Stott, pp. 95–100

- McConnell Stott, p. 109

Bibliography

- Andrews, Richard (2008). The Commedia dell'arte of Flamino Scala: A Translation and Analysis of 30 Scenarios. Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810862074.

- Banham, Martin, editor (1995). The Cambridge Guide to the Theatre (new edition). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521434379.

- Beijer, Agne; Duchartre, Pierre-Louis (1928). Recueil de plusieurs fragments des premières comédies italiennes qui on été représentées en France sous le règne de Henri III. Recueil, dit de Fossard, conservé au musée national de Stockholm. Paris: Duchartre & Van Buggenhoudt. OCLC 963462417.

- Duchartre, Pierre-Louis (1929; Dover reprint 1966). The Italian Comedy. London: George G. Harrap and Co., Ltd. ISBN 0486216799.

- Ferrone, Siro (2006). Arlecchino. Vita e avventure di Tristano Martinelli attore. Bari: Lateraz. ISBN 9788842078685.

- Gambelli, Delia (1993). Arlecchino a Parigi. Rome: Bulzoni. ISBN 9788871195803.

- Henke, Robert (2002). Performance and Literature in the Commedia dell'arte. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521172387.

- Katritzky, M. A. (2006). The Art of Commedia: A Study in the Commedia dell'arte, 1560-1620, with Special Reference to the Visual Records. Amsterdam & New York: Rodopi B. V. ISBN 9789042017986.

- Lea, K.M. (1934). Italian popular comedy: a study in the Commedia dell'arte, 1560-1620, with special reference to the English stage. 2 vols. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- McConnell Stott, Andrew (2009). The Pantomime Life of Joseph Grimaldi. Edinburgh:Canongate Books Ltd. ISBN 9781847677617.

- Neville, Giles (1980). Incidents In the Life of Joseph Grimaldi. London: Jonathan Cape Ltd. ISBN 0224018698.

- Oreglia, Giacomo (1968). The Commedia dell'arte. New York: Hill and Wang. pp. 55–70. ISBN 9780809005451.

- Rudlin, John (1994). Commedia dell’Arte, An actor’s handbook. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415047708.

- Rudlin, John; Crick, Olly (2001). Commedia dell'arte: A Handbook for Troupes. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415204088.

- Sand, Maurice (1860). Masques et Bouffons. Comédie italienne, vol. 1. Paris: Michel Levy Frères. Copy at Google Books.

- Scuderi, Antonio. "Arlecchino Revisited: Tracing the Demon from the Carnival to Kramer and Mr. Bean." Theatre History Studies, vol. 20, 2000., pp. 143–155.

- Sterling, Charles (1943). "Early Paintings of the Commedia dell'arte in France." Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, New ser., v. 2, no. 1 (Summer, 1943). JSTOR 3257039.

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.