Triballi

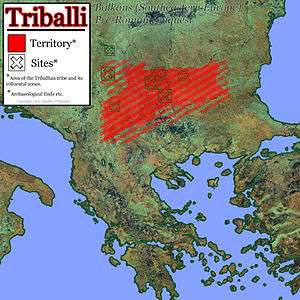

The Triballi (Greek: Τριβαλλοί, Triballoí) were an ancient tribe whose dominion was around the plains of modern southern Serbia,[1][2] northern part of North Macedonia and western Bulgaria, at the Angrus and Brongus[3] (the South and West Morava) and the Iskar River, roughly centered where Serbia and Bulgaria are joined.[2]

The Triballi were a Thracian tribe that received influences from Celts, Scythians and Illyrians.[4][5]

History

Based on the archaeological findings, the history of the Triballi can be divided in four periods: Proto-Triballian (1300-800 BC), Early Triballian (800-600 BC), Triballian (600–335 BC) and period from 335 BC until Roman conquest.[6]

In 424 BC, they were attacked by Sitalkes, king of the Odrysae, who was defeated and lost his life in the engagement.[3][7] They were pushed to the east by the invading Autariatae, an Illyrian tribe; the date of this event is uncertain.[3]

In 376 BC, a large band of Triballi under King Hales crossed Mount Haemus and advanced as far as Abdera;[3] they had backing from Maroneia and were preparing to besiege the city when Chabrias appeared off the coast, with the Athenian fleet,[3] and organized a reconciliation.[7]

In 339 BC, when Philip II of Macedon was returning from his expedition against the Scythians, the Triballi refused to allow him to pass the Haemus unless they received a share of the booty. Hostilities took place, in which Philip was defeated[3] and wounded by a spear in his right thigh, but the Triballi appear to have been subsequently subdued by him.[8][3]

After the death of Philip, Alexander the Great passed through the lands of the Odrysians in 335-334 BC, crossed the Haemus ranges and after three encounters (Battle of Haemus, Battle at Lyginus river, Battle at Peuce Island) defeated and drove the Triballians to the junction of the Lyginus at the Danube.[3] 3,000 Triballi were killed, the rest fled. Their king Syrmus (eponymous to Roman Sirmium) took refuge on the Danubian island of Peukê, where most of the remnants of the defeated Thracians were exiled. The successful Macedonian attacks terrorized the tribes around the Danube; the autonomous Thracian tribes sent tributes for peace, Alexander was satisfied with his operations and accepted peace because of his greater wars in Asia.

They were attacked by Autariatae and Celts in 295 BC.[9]

The punishment inflicted by Ptolemy Keraunos on the Getae, however, induced the Triballi to sue for peace. About 279 BC, a host of Gauls (Scordisci[10]) under Cerethrius defeated the Triballi with an army of 3,000 horsemen and 15,000 foot soldiers. The defeat pushed the Triballi further to the east.[11] Nevertheless, they continued to cause trouble to the Roman governors of Macedonia[3] for fifty years (135 BC–84 BC).

The Illyrian Dardani tribe settled in the southwest of the Triballi area in 87 BC. The Thracian place names survives the Romanization of the region.[12]

Pliny the Elder (23-79 AD) registers them as one of the tribes of Moesia.[13]

In the time of Ptolemy (90–168 AD), their territory was limited to the district between the Ciabrus (Tzibritza) and Utus (Vit) rivers, part of what is now Bulgaria; their chief town was Oescus.[3]

Under Tiberius, mention is made of Triballia in Moesia; and the Emperor Maximinus Thrax (reigned 235–237) had been a commander of a squadron of Triballi. The name occurs for the last time during the reign of Diocletian, who dates a letter from Triballis.[3][14]

Legacy

Exonym of Serbs

The term "Triballians" appears frequently in Byzantine and other European works of the Middle Ages, referring exclusively to Serbs.[15][16][17][18][19] Some of these authors clearly explain that "Triballian" is synonym to "Serbian".[20][21][22][23][24] For example, Niketas Choniates (or Acominatus, 1155–1215 or-16) in his history about Emperor Ioannes Komnenos: "... Shortly after this, he campaigned against the nation of Triballians (whom someone may call Serbians as well) ..."[25] or the much later Demetrios Chalkondyles (1423–1511), referring to an Islamized Christian noble: "... This Mahmud, son of Michael, is Triballian, which means Serbian, by his mother, and Greek by his father."[26] or Mehmed the Conqueror when referring to the plundering of Serbia.[27]

In the 15th century, a coat of arms of "Tribalia", depicting a wild boar with an arrow pierced through the head (see Boars in heraldry), appeared in the supposed Coat of Arms of Emperor Stefan Dušan 'the Mighty' (r. 1331–1355).[28] The motif had, in 1415, been used as the Coat of Arms of the Serbian Despotate and is recalled in one of Stefan Lazarević's personal Seals, according to the paper Сабор у Констанци.[29] Pavao Ritter Vitezović also depicts "Triballia" with the same motif in 1701[30] and Hristofor Zhefarovich again in 1741.[31]

With the beginning of the First Serbian Uprising, the Parliament adopted the Serbian Coat of Arms in 1805, their official seal depicted the heraldic emblems of Serbia and Tribalia.[32]

The written sources on the Triballi are scarce but the archaeological remains are abundant. The scientific research of the Triballi was boosted with Fanula Papazoglu's book The Central Balkan Tribes in Pre-Roman Times (1968 in Serbia, 1978 in English). Other historians and archaeologists who wrote on the Triballi include Milutin Garašanin, Dragoslav Srejović, Nikola Tasić, Rastko Vasić, Miloš Jevtić and, especially, Milorad Stojić (Tribali u arheologiji i istorijskim izvorima, 2017). Even though the two names were used as synonyms by some Byzantine sources and certain heraldic inheritance, Serbian official historiography is not equalizing the Serbs and the Triballi, nor does it fabricate a cultural continuity between the two.[6]

Archaeological findings

Bulgaria

Serbia

Archeological findings prove that the Triballi inhabited the Morava Valley (Great Morava and South Morava) region in the Iron Age.[33]

- In 2005, several possibly Triballi graves were found at the Hisar Hill in Leskovac, southeastern Serbia.[34]

- In June 2008, a Triballi grave was found together with ceramics (urns) in Požarevac, central-eastern Serbia.[35]

- Triballi tomb unearthed at Ljuljaci, west of Kragujevac, central Serbia.[36]

References

- Papazoglu 1978, p. 58-61.

- George Grote: History of Greece: I. Legendary Greece. II. Grecian history to the reign of Peisistratus at Athens, Vol 12, 1856 "...from the plain of Kossovo in modern Servia northward towards the Danube..."

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 261.

- Alexander the Great at War: His army - His battles - His Enemies (General Military) by Ruth Sheppard, 2008, page 69, "... for savagery and their contact with the Scythians, Illyrians and Celts left influences upon the Triballi, and these influences may be ..."

- The Thracians 700 BC–AD 46 (Men-at-Arms) by Christopher Webber and Angus McBride, 2001, ISBN 1-84176-329-2, page 6

- Sofija Petković, Milorad Stojić (20 January 2018). "Tribali - najstariji stanovnici Srbije" [Triballi - the oldest inhabitants of Serbia]. Politika-Kulturni dodatak (in Serbian). pp. 06–07.

- The Greek Settlements in Thrace Until the Macedonian Conquest at Google Books

- Interpreting a Classic: Demosthenes and His Ancient Commentators at Google Books

- The Thracians by Ralph F. Hoddinott, 1981, ISBN 0-500-02099-X, Chapter "South and para-Dunavian Thrace", "Thracian art in the valley of the Lower Danube", page 197

- Appianus

- "Theodossiev" (PDF). Retrieved 2015-09-13.

- "BALCANICA XXXVII" (PDF). Belgrade. 2007. Retrieved 2015-09-13.

- The Cambridge Ancient History at Google Books

- Encyclopædia Britannica: a new survey of universal knowledge, Volume 22, (1956) p. 465

- The development of the Komnenian army: 1081–1180 at Google Books

- Stuck Whilhelm (Guilielmus Stukius Tigurinus), Comments on Arriani historici et philosophi Ponti Euxini et maris Erythraei Periplus, Lugduni, 1577, p. 51

- John Foxe (1517–1587) Acts and Monuments, Published by R.B. Seeley & W. Burnside, London, 1837, vol. 4, p. 27

- "Balkan history - Thracian tribes". eliznik.org.uk. Retrieved 2015-09-13.

- The letters of Manuel II Palaeologus at Google Books

- Potter, G. R. (1938). "Reviews of Books". The English Historical Review. 53 (209): 129–131. doi:10.1093/ehr/LIII.CCIX.129. JSTOR 554790.

- Mehmed II the Conqueror and the fall of the Franco-Byzantine Levant to the Ottoman Turks Page 65, 77: "Triballians = Serbs"

- The letters of Manuel II Palaeologus, p. 48, at Google Books: "The Triballians are the Serbs"

- The Journal of Hellenic studies Page 48: "Byzantine historians [...] calling [...] Serbs Triballians"

- Studies in late Byzantine history and prosopography, p. 228, at Google Books: "Serbs (were) Triballians"

- Historia ed J. van Dieten, Nicetae Choniatae historia ..., Berlin, DeGruyter, 1975, chapter "Reign of Lord Ioannes Komnenos", pp. 4-47 (in medieval Greek language)

- D. Chalkocondyles (Chalkondyles) cited in C. Paparrigopoulos History of the Greek nation, Athens, 1874, vol. 5, p. 489, in Greek language.

- History of Mehmed the Conqueror, p. 115, at Google Books

- The first Serbian uprising and the restoration of the Serbian state, p. 164

- "- О грбу Града :: Званичан сајт града Крагујевца". kragujevac.rs. Retrieved 2015-09-13.

- Stemmatographia sive armorum Illyricorum delineatio, descriptio et restitutio, 1701

- Balkanika, Issue 28, p. 216

- East European quarterly, Volume 6, p. 346

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-07-05. Retrieved 2010-07-05.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Praistorijska kopča". b92.net. Retrieved 2015-09-13.

- "www.jasatomic.org.yu - Katastrofalna poplava u mestu Jaša Tomić opština Sečanj (BANAT)". Archived from the original on 2009-02-08. Retrieved 2015-09-13.

- "Tribalski grobovi u LjuljacimaLes sépultures triballes de Ljuljaci". cat.inist.fr. Retrieved 2015-09-13.

Sources

- Papazoglu, Fanula (1978). The Central Balkan Tribes in pre-Roman Times: Triballi, Autariatae, Dardanians, Scordisci and Moesians. Amsterdam: Hakkert. ISBN 9789025607937.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stojić, M. (2001). "Kulturne tradicije na prostoru na kome će se formirati i razvijati Tribali". Zbornik Radova Filozofskog Fakulteta u Prištini. 31: 253–264.

- Vasić, Rastko (1972). "Notes on the Autariatae and Triballi". Balcanica. III.

- Vasić, Rastko (1992). "Pages from the history of the Autoriatae and Triballoi". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Bouzek, J. and Ondřejová, I., 1990. The Rogozen treasure and the art of the Triballoi. Eirene, 27, pp. 81–91.

- Jevtić, M., 2006. Sacred groves of the Tribali on Miroč Mountain. Starinar, (56), pp. 271–290. DOI:10.2298/STA0656271J

- Jevtić, M. and Peković, M., 2007. Mihajlov ponor on Miroč: Tribal cult places. Starinar, (57), pp. 191–219. DOI:10.2298/STA0757191P

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thracians. |