Treaty of the Three Black Eagles

The Treaty of the Three Black Eagles, or Treaty of Berlin, was a secret treaty signed in September and December 1732 between the Austrian Empire, the Russian Empire and Prussia.

It concerned the joint policy of the three powers regarding to the succession of the Polish throne in light of the expected death of King Augustus II of Poland (and Elector of Saxony from the House of Wettin) and the Polish custom of royal elections. It intended to exclude the candidacies of Augustus' son, Frederick Augustus, and of Stanislas Leszczynski, who had already been king of Poland from 1704 to 1709.

However, in 1733, as Stanislas was about to be elected, Russia and Austria signed Löwenwolde's Treaty (on 19 August 1733) to support Frederick Augustus. Stanislas eventually had to leave Poland, and Frederick Augustus was elected as Augustus III of Poland.

Name

The usual name comes from the fact all three signatories used a black eagle as a state symbol,[1] in contrast to the white eagle, a symbol of Poland. Another name is the Treaty of Berlin, where it was signed by Prussia (Russia and Austria had signed on 13 September 1732 and were joined by Prussia on 13 December).

Terms

The three powers agreed that they would oppose another candidate from the House of Wettin as well as the candidacy of the pro-French Pole Stanisław Leszczyński, the father-in-law of Louis XV.[2] Instead, they chose to support either Infante Manuel, Count of Ourém, brother of the Portuguese king,[3] or a member of the Piast family.[4]

The Treaty of the Three Black Eagles had several goals. None of the three parties seriously supported Infante Manuel.[5] The agreement had provisions for all three powers to agree that it was in their best interest that their common neighbour, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, did not undertake any reforms that might strengthen it[6] and for its elected monarch to be friendly towards them.[2] In addition to the obvious, increasing the influence of the three powers over the Commonwealth, Austria and Russia also discreetly wanted to reduce the possibility of a French-Prussian-Saxon alliance. Prussia received promises of support for its interests in Courland (now southern and western Latvia).[3]

Löwenwolde's Treaty

The political situation changed rapidly, and the Treaty of the Three Black Eagles was superseded soon after it had been formulated. With the death of Augustus II on 1 February 1733, Austria and Russia distanced themselves from the earlier treaty, which was never ratified by the Empress of Russia.[3] Their primary goal, the disruption of the French-Saxon-Prussian alliance, had already been achieved and so they sought to secure support from various Polish and Saxon factions. Thus, on 19 August 1733, Russia and Austria entered into the Löwenwolde's Treaty with Saxony in the person of the new elector, Frederick Augustus II of Saxony. The treaty was named after one of the chief diplomats involved in the negotiations, the Russian Karl Gustav von Löwenwolde.

The terms of Löwenwolde's Treaty were straightforward. Russia would provide troops to ensure Frederick Augustus's election and coronation, and Frederick Augustus would, as the Polish king, recognise Anna Ivanovna as Empress of Russia, relinquish Polish claims to Livonia and remain unopposed to Russian interests[7] in Courland.[8] Austria received a promise that as king, Frederick Augustus would both renounce any claim to the Austrian succession and respect the Pragmatic Sanction of 1713.[2]

Aftermath

Prussia allowed the French candidate, Leszczyński, safe passage across their lands[9] and continued to oppose the election of Frederick Augustus.[10] Both Austria and Russia publicly declared in advance that they would not recognise Leszczyński if he was elected.[2] However, the election sejm in Wola went ahead and picked Leszczyński on 12 September 1733, which was announced by the interrex, Primate Potocki.[2][11] Fiplomatic promises[2] and the arrival of Russian troops outside Warsaw on 20 September[8] caused a "rump" group, led by Michael Wisniowiecki (Great Chancellor of Lithuania) and Teodor Lubomirski (governor of Kraków) together with the Bishop of Poznań (Stanisław Józef Hozjusz) and the Bishop of Kraków (Jan Aleksander Lipski) to decamp to another Warsaw suburb, where they held a new election, under the protection of the Russian troops, picking Frederick Augustus II of Saxony, who became Augustus III of Poland.[2]

The interference of various foreign powers into the Polish election led to the War of the Polish Succession (1733–1738), between Augustus III, with his foreign allies Austria and Russia, against the supporters of Leszczyński, allied with France. Prussia reluctantly sent 10,000 troops.[3] In the Treaty of Vienna of 1738, which formally ended the war, Leszczyński renounced his claim to the Polish throne[12] and was made Duke of Lorraine in compensation.[9]

Name

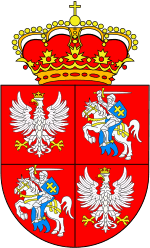

The Three Black Eagles are referencing the respective coats of arms of the involved countries, as contrasted to the Polish White Eagle.

The State Emblem of the Russian Empire

The State Emblem of the Russian Empire.png) The Coat of arms of the Austrian Empire

The Coat of arms of the Austrian Empire The Black Eagle of Prussia

The Black Eagle of Prussia Coat of arms of Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the White Eagle was the coat of arm of Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, Pogoń Litewska was coat of arm of Grand Duchy of Lithuania

Coat of arms of Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the White Eagle was the coat of arm of Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, Pogoń Litewska was coat of arm of Grand Duchy of Lithuania

Notes

- Cierlińska, Hanna (1982) A Panorama of Polish History Interpress Publishers, Warsaw, Poland, page 73, ISBN 83-223-1997-5

- Corwin, Edward Henry Lewinski (1917) The political History of Poland Polish Book Importing Company, New York, page 286–288, OCLC 626738

- Tuttle, Herbert and Adams, Herbert Baxter (1883) History of Prussia. Houghton, Mifflin and Company, pages 369–371

- Gieysztor, Aleksander, et al. (1979) History of Poland PWN, Polish Scientific Publishers, Warsaw, Poland, page 244, ISBN 83-01-00392-8

- Schlosser, Friedrich Christoph (1844) History of the eighteenth century and of the nineteenth till the overthrow of the French empire: Volume III Chapman and Hall, London, page 294, OCLC 248862784

- Marácz, László Károly (1999) Expanding European unity: Central and Eastern Europe Rodopi, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, page 134, ISBN 90-420-0455-X

- That effectivity meant supporting the rule of Ernest Biron, a Russian court favourite. Corwin, Edward Henry Lewinski (1917) The Political History of Poland Polish Book Importing Company, New York, page 288, OCLC 626738

- Ragsdale, Hugh (1993) Imperial Russian foreign policy Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England, page 32–33, ISBN 0-521-44229-X

- Lindsay, J. O. (1957) The New Cambridge Modern History Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England, page 205, ISBN 0-521-04545-2

- Kelly, Walter Keating (1854) The History of Russia: From the Earliest Period to the Present Time Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, pages 408–409

- William Macpherson indicated that Leszczyński's election was caused partly by French gold. Macpherson, William (editor) (1845) "Chapter CXXXIII Annals of France, from the Accession of Louis XV, to the Period following the Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle" Encyclopaedia Metropolitana Volume XIII: History and Biography Volume 5 B. Fellowes, London, page 144, OCLC 4482450

- Stanisłas Leszczyński renounced the throne 'voluntarily and for the sake of peace', which implied that his election had been legal. Lindsay, J. O. (1957) The New Cambridge Modern History Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England, page 205, ISBN 0-521-04545-2