Totora, Cochabamba

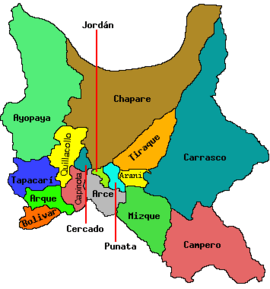

Totora (/toʊtʊərɑː/) (in Hispanicized spelling), Tutura or T'utura (Aymara and Quechua for Schoenoplectus californicus, an aquatic plant)[2][3][4] is a town in the Carrasco Province of the Cochabamba Department in Bolivia. It is the capital and most-populous place of the Totora Municipality. As of the 2012 census, the population is 1,925. The first settlers were Inca Indians. Totora was officially settled in 1876, and declared a town by the Government of Bolivia in 1894.

Totora | |

|---|---|

town | |

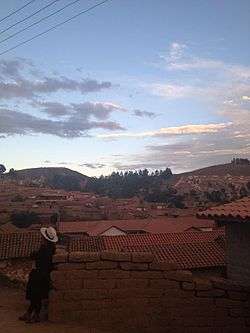

Skyline, 2012 | |

Flag | |

| Nickname(s): City of the Pianos | |

Location of Cochabamba Department in Bolivia | |

Totora Location of in Cochabamba Department | |

| Coordinates: 17°44′8″S 65°11′31″W | |

| Country | Bolivia |

| Department | Cochabama |

| Province | Carrasco |

| Settled | 24 June 1876 |

| Incorporated (city) | 27 October 1894 |

| Named for | Tjutura, now-extinct aquatic plant from the area |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–council government |

| • Mayor | Edmundo Novillo (MAS-IPSP) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 42 km2 (16 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 2,805 m (9,203 ft) |

| Population (2012) | |

| • Total | 1,925 |

| • Density | 46/km2 (120/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Totoreños |

| Ethnicity | |

| • Quechua | 88.6% |

| • Aymara | 2.2% |

| • Guaraní | 1.4% |

| • Chiquitano | 0.3% |

| • Other | 7.3% |

| Time zone | UTC-4:00 (BOT) |

| Country code | +591 4 |

| Website | www |

History

The first settlers of the city were from the Inca Empire.[5] From 1530 until 1722, the land Totora occupied was in control of Spaniards who mainly used the land for cocoa production.[6] The first time the town was mentioned was in 1639, when a landowner named Don Fernando García Murillo had established a chaplaincy.[7] The city was officially settled on 24 June 1876[8] after the Mizque Municipality was divided into the Mizque and the Totora Municipality.[9] It was officially declared a city by the Bolivian Government on 27 October 1894.[10] The first residents of Totora were wealthy landowners, traders, and textile artisans. It was also a trading stop between west and east of Bolivia.[7]

On 22 May 1998, a 6.8 MW earthquake hit the Totora and Aiquile area. There were four foreshocks—ranging from 2.7 to 5.8—and consistent aftershocks until 27 May.[11] 105 people were killed,[12] and it was considered a "national tragedy" by then-President Hugo Banzer.[13]

In 2000, Totora was declared a "Cultural Heritage of Humanity" by the United Nations.[14]

Geography

Climate

| Totora | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Using the reference point of Totora and Mizque, the town has a subhumid climate, according to the AMDECO.[16] Compared to other towns in the area, Totora is the driest, with more sparse vegetation. The average low for the year is 0.3 °C (32.5 °F), and the average high is 18.3 °C (64.9 °F). The hottest month is November, with an average high of 21 °C (70 °F), and the coldest months are June and July, with an average low of −7 °C (19 °F). On average, Totora receives 348 millimetres (13.7 in) of precipitation per year, where January is the wettest month.[15]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1845 | 1,000 | — |

| 1900 | 3,501 | +2.30% |

| 1992 | 1,347 | −1.03% |

| 2001 | 1,597 | +1.91% |

| 2012 | 1,925 | +1.71% |

| Sources:[17][18][19][20][21] | ||

According to the 2012 Bolivian census, the population of Totora was 1,925, an annual increase of 1.71% from 2001. The increase was unexpected, as the Association of Municipality of Cochabamba (AMDECO) projected the population to drop to 1,469.[22] There were 892 (46.33%) men and 1,033 (53.66%) women, for a ratio of 1.15 women to men. In 2012, there were 1,069 homes, and 457 families, for an average household of 1.80 persons.[21] Throughout history, the highest population of the city was 3,501 in 1992;[19] the lowest population was 1,000 in 1845.[17] With an estimated area of 42 km2 (16 sq mi), Totora has a population density of 46 people/km2.

Within the municipality Totora is the most-populous place, with 13.1% of the total population and, as of 2012, is the only town in its municipality with a population over 1,000.[21] As of 2001, the racial makeup of the town was 88.6% Quechua, 2.2% Aymara, 1.4% Guaraní, 0.3% Chiquitano, and 7.3% from other races.[23] As to languages, a majority of the population (65.4%) speak either Spanish or Quechua[24] or both language. As of 2005, 98% of the population are of the Catholic religion and 2% are Evangelical.[25]

Cityscape

Totora is noted for having colonial-style building and architecture.[8][14] Because of the town's topography, the streets have an atypical distribution. The most common style of house includes adobe walls, land floors, and cement roofing.[26] From 1999 to 2005, 44.2% of the households use firewood to power their house, 55.1% use gas power, and 0.6% use other means.[27] In 2011, solar panels were introduced in the town to power its schools, with the help of the European Union.[28]

The protected Carrasco National Park is northeast of Totora. Created in 1991, the park has an area of 6,226 km2 (2,404 sq mi) and it ranges in altitude from 300 and 4,700 m (980 and 15,420 ft).[29] It is estimated that there are 3,000 plant species, estimated 700 species of birds, and 382 confirmed type of wildlife located in the park.[30] The main tourist attractions are The House of Culture, which used to be a mansion but is now a museum; the colonial bridges; the plaza; Phaqcha (Pajcha), a 30 m (98 ft) waterfall; Julpe, a place that holds cave paintings.[31]

Culture

Economy

In 2013, a deal was made with the Local Committee for the Productive Development of Wheat and Potato Township Totora to have around 300 families in Totora produce wheat for five cereal companies in Cochabamba.[32]

Law and government

The current mayor of Totora is Edmundo Novillo.[33]

Education

There are three schools located in Totora: José Carrasco Torrico High school, named after ex-Vice President José Carrasco Torrico, Martin Mostajo Middle school and La Paz Middle School. The college has 320 students.[34] The middle school was constructed in 2013 and cost Bs. 2,000,000 ($289436). It holds 11 classrooms and supports up to 250 students.[35] As of 2001, the literacy rate in Totora is 82.4%, lower than the country average of 86.7%.[36][37]

Transportation

The main two ways to reach Totora by road are from Route 7, if coming from Cochabamba,[38] and Route 5, if coming from Sucre.[39] The Bolivian Department of Education is in the process of making a road from Tarata to Totora, since both are historic towns.[40]

Notes

- Viehoff, Ivan. "Touring Notes: Bolivia". Transamazonica. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- Teofilo Laime Ajacopa, Diccionario Bilingüe Iskay simipi yuyayk'ancha, La Paz, 2007 (Quechua-Spanish dictionary)

- Diccionario Quechua - Español - Quechua, Academía Mayor de la Lengua Quechua, Gobierno Regional Cusco, Cusco 2005 (Quechua-Spanish dictionary)

- Radio San Gabriel, "Instituto Radiofonico de Promoción Aymara" (IRPA) 1993, Republicado por Instituto de las Lenguas y Literaturas Andinas-Amazónicas (ILLLA-A) 2011, Transcripción del Vocabulario de la Lengua Aymara, P. Ludovico Bertonio 1612 (Spanish-Aymara-Aymara-Spanish dictionary)

- http://www.totora.org/es2/primeros_pobladores_de_totora.htm

- "Breve Resena Historica" [Brief Historical Survey] (in Spanish). Totora.org. 1 June 2009. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-02-02. Retrieved 2014-01-20.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Giiereca, Luis (7 July 2013). "Totora Intenta Mantener Su Arquitectura Colonial" [Totora Tries To Maintain Its Colonial Architecture]. Los Tiempos (in Spanish). Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- National Immigration Bureau & Statistical and Geographic Propaganda 1904, p. 627

- "Totora: City Charter". Totora.org. 1 June 2009. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- Condori, Cristina. "Earthquake in the Region Aiquile and Totora". International Institute of Seismology and Earthquake Engineering. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- "Toll Put At 105 In Bolivian Quake". The Toledo Blade. 28 May 1998. p. 2.

- "Rescue Efforts Continue after Bolivian Quake: At Least 60 Dead, 100 Missing in Remote Region". CNN. 22 May 1998.

- http://cochabambabolivia.net/totora

- "Totora Monthly Climate Average, Bolivia". World Weather Online. Retrieved December 14, 2013.

- AMDECO 2011, p. 20

- Gotha 1868, p. 181

- Chisholm 1910, p. 172

- "Estadisticas Sociales: Poblacion 1992" [Social Statistics Population 1992] (in Spanish). Instituto Nacional de Estadistica de Bolivia. 2 November 2011. Select COCHABAMBA in the Departamento box, CARRASCO in the Provincia box, TOTORA (PRIMERA) in the Seccion Muninipal box, TOTORA in the Canton box, TOTORA in the Ciudad o localidad box, and click Ver infomacion to see verify data.

- "Censo de Poblacion y Vivienda – 2001" [Census of Population and Housing – 2001]. National Statistics Institute of Bolivia. 2001. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- "Censo de Poblacion y Vivienda 2012" [Census of Population and Housing 2012] (in Spanish). National Statistics Institute of Bolivia. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- AMDECO 2011, p. 67

- AMDECO 2011, p. 72

- AMDECO 2011, p. 73

- AMDECO 2011, p. 74

- AMDECO 2011, pp. 83–84

- AMDECO 2011, pp. 113–114

- "Escuelas del área rural usan energía eólica y solar" [Schools in rural areas using solar and wind energy]. Los Tiempos (in Spanish). 23 July 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- SERNAP nd, pp. 1–2

- SERNAP nd, pp. 3

- http://www.boliviaentusmanos.com/turismo-bolivia/destino.php?item=130

- Central Newsroom (8 May 2013). "El trigo de Totora nutre a 5 industrias alimenticias" [Totora wheat nourishes 5 food industries]. La Prensa (in Spanish). La Paz. Retrieved 29 December 2013.

- Yaksic, Claudia (2 October 2013). "Ley Hará Difícil Saqueo Y Destrucción De Patrimonio" [Law Will Make It Difficult Looting And Destruction Of Property]. Los Tiempos (in Spanish). Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- "Colegio José Carrasco aclamó a Decano de la Prensa Nacional" [College Dean hailed José Carrasco National Press]. El Diario (in Spanish). 14 May 2004. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- "Evo entrega tres obras en la Llajta" [Evo delivers three works in Llajta]. Los Tiempos (in Spanish). 8 October 2013. Retrieved 29 December 2013.

- AMDECO 2011, pp. 71–72

- http://www.indexmundi.com/facts/bolivia/literacy-rate

- "Cochabamba, Bolivia to Totora, Bolivia". Google Maps. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- "Sucre, Bolivia to Totora, Bolivia". Google Maps. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- Carrillo, Karen (21 September 2013). "Potencian el turismo, la historia y tradición del valle" [Enhance tourism, history and tradition of the Valley]. Los Tiempos (in Spanish). Retrieved 12 January 2014.

References

- AMDECO (2011). Plan de Desarollo Municipal: Totora 2007–2011 [Municipal Development Plan: Totora 2007–2011] (Report) (in Spanish). AMDECO.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chisholm, Chris (1910). The Encyclopædia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature and General Information. 4 (11 ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica Company. OCLC 14782424.

- Gotha, Hermann (1868). Geographisches Jahrbuch. 2. Justus Perthes. OCLC 1780902.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Oficina Nacional de Inmigración, Estadística y Propaganda Geográfica (1904). "Boletín de la Oficina Nacional de Inmigración" [Bulletin of the National Immigration Bureau] (in Spanish) (37–48). La Paz: National Immigration Bureau. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - SERNAP (nd). "Parque Nacion Carrasco" [Carrasco National Park] (PDF) (Press release) (in Spanish). SERNAP.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Villarroel, Andrés (1928). Totora: Notas Sobre Su Pasado [Totora: Notes On Its Past]. Editorial López.