Tommy Cooper

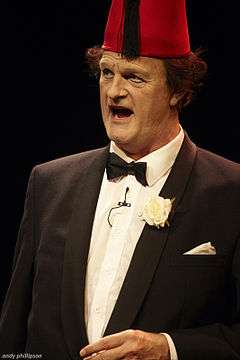

Thomas Frederick Cooper (19 March 1921 – 15 April 1984) was a Welsh-born British prop comedian and magician. As an entertainer, his appearance was large and lumbering at 6 feet 4 inches (1.93 m),[1] and he habitually wore a red fez when performing. He initially served in the British Army for seven years, before eventually developing his conjuring skills and becoming a member of the The Magic Circle. Although he spent time on tour performing his magical act, which specialised on magic tricks that appeared to "fail", he rose to international prominence when his career moved into television, with programmes for London Weekend Television and Thames Television.

Tommy Cooper | |

|---|---|

Cooper, c. 1982 | |

| Born | Thomas Frederick Cooper 19 March 1921 Caerphilly, Glamorgan, Wales |

| Died | 15 April 1984 (aged 63) |

| Cause of death | Heart attack |

| Occupation | Prop comedian, magician |

| Years active | 1947–1984 |

| Spouse(s) | Gwen Henty ( m. 1947) |

| Children | Victoria Cooper (b. 1953) Thomas Henty (b.1956 d. 1988) |

By the end of the 1970s, Cooper slipped into heavy smoking and drinking, which impacted his career and his health, effectively ending offers to front new programmes and regulating him as a guest star on other entertainment shows. Ill health eventually claimed his life when, on 15 April 1984, Cooper died of a heart attack live on television.[2]

Early life

Thomas Frederick Cooper was born on 19 March 1921 at 19 Llwyn-On Street in Caerphilly, Glamorgan.[3] He was delivered by the woman who owned the house in which the family were lodging. His parents were Thomas H. Cooper, a Welsh recruiting sergeant in the British Army and later coal miner, and Catherine Gertrude (née Wright), Thomas's English wife from Crediton, Devon.[3][4]

To escape from the heavily polluted air of Caerphilly, his father accepted the offer of a new job and the family moved to Exeter, Devon, when Cooper was three. It was in Exeter that he acquired the West Country accent that became part of his act.[5] When he was eight an aunt bought him a magic set and he spent hours perfecting the tricks.[6] In the 1960s, his brother David (born 1930)[7] opened D. & Z. Cooper's Magic Shop on the high street in Slough, Berkshire.[8]

After school Cooper became a shipwright in Southampton. In 1940 he was called up as a trooper in the Royal Horse Guards, serving for seven years. He joined Montgomery's Desert Rats in Egypt. Cooper became a member of a Navy, Army and Air Force Institutes (NAAFI) entertainment party, and developed an act around his magic tricks interspersed with comedy. One evening in Cairo, during a sketch in which he was supposed to be in a costume that required a pith helmet, having forgotten the prop Cooper reached out and borrowed a fez from a passing waiter, which got huge laughs.[9] He wore a fez when performing after that, the prop later being described as "an icon of 20th-century comedy".[10]

Development of the act

Cooper was demobbed after seven years of military service and took up show business on Christmas Eve 1947. He later developed a popular monologue about his military experience as "Cooper the Trooper". He worked in variety theatres around the country and at many night spots in London, performing as many as 52 shows in one week.[11]

Cooper developed his conjuring skills and became a member of The Magic Circle, but there are various stories about how and when he developed his delivery of "failed" magic tricks:[9]

- He was performing to his shipbuilding colleagues when everything went wrong, but he noticed that the failed tricks got laughs.

- He started making "mistakes" on purpose when he was in the Army.

- His tricks went wrong at a post-war audition, but the panel thoroughly enjoyed them anyway.

To keep the audience on their toes Cooper threw in an occasional trick that worked when it was least expected.

Career

Cooper was influenced by Laurel and Hardy,[12] Will Hay,[13] Max Miller,[12] Bob Hope,[12] and Robert Orben.[14]

In 1947 Cooper got his big break with Miff Ferrie, at that time trombonist in a band called The Jackdaws, who booked him to appear as the second-spot comedian in a show starring the sand dance act Marqueeze and the Dance of the Seven Veils. Cooper then began two years of arduous performing, including a tour of Europe and a stint in pantomime, playing one of Cinderella's ugly sisters. The period culminated in a season-long booking at the Windmill Theatre, where he doubled up doing cabaret. In one week he performed 52 shows. Ferrie remained Cooper's sole agent for 37 years, until Cooper's death in 1984. Cooper was supported by a variety of acts, including the vocal percussionist Frank Holder.

Cooper rapidly became a top-liner in variety with his turn as the conjurer whose tricks never succeeded, but it was his television work that raised him to national prominence. After his debut on the BBC talent show New to You in March 1948 he began starring in his own shows, and was popular with audiences for nearly 40 years, notably through his work with London Weekend Television from 1968 to 1972 and with Thames Television from 1973 to 1980. Thanks to his many television shows during the mid-1970s he was one of the most recognisable comedians in the world.

John Fisher writes in his biography of Cooper: "Everyone agrees that he was mean. Quite simply he was acknowledged as the tightest man in show business, with a pathological dread of reaching into his pocket." One of Cooper's stunts was to pay the exact taxi fare and when leaving the cab slip something into the taxi driver's pocket, saying, "Have a drink on me." That something would turn out to be a tea bag.[15]

By the mid-1970s alcohol had started to erode Cooper's professionalism and club owners complained that he turned up late or rushed through his show in five minutes. In addition he suffered from chronic indigestion, lumbago, sciatica, bronchitis and severe circulation problems in his legs. When Cooper realised the extent of his maladies he cut down on his drinking, and the energy and confidence returned to his act. However, he never stopped drinking and could be fallible: on an otherwise triumphant appearance with Michael Parkinson he forgot to set the safety catch on the guillotine illusion into which he had cajoled Parkinson, and only a last-minute intervention by the floor manager saved Parkinson from serious injury or worse.[16]

Cooper was a heavy smoker as well as an excessive drinker. He experienced a decline in health during the late 1970s, suffering a heart attack in 1977 while performing a show in Rome. Three months later he was back on television in Night Out at the London Casino.

By 1980 his drinking meant that Thames Television would not give him another starring series, and Cooper's Half Hour was his last. He did continue to appear as a guest on other television shows, however, and worked with Eric Sykes on two Thames productions in 1982.

Death on live television

On 15 April 1984 Cooper collapsed from a heart attack in front of millions of television viewers, midway through his act on the London Weekend Television variety show Live from Her Majesty's, transmitted live from Her Majesty's Theatre in Westminster, London.[17]

An assistant had helped him put on a cloak for his sketch, while Jimmy Tarbuck, the host, was hiding behind the curtain waiting to pass him different props that he would then appear to pull from inside his gown.[17] The assistant smiled at him as he slumped down, believing that it was part of the act.[18] Likewise, the audience gave "uproarious" laughter as he fell backwards, gasping for air.[17]

At this point Alasdair MacMillan, the director of the television production, cued the orchestra to play music for an unscripted commercial break (noticeable because of several seconds of blank screen while LWT's master control contacted regional stations to start transmitting advertisements)[17] and Tarbuck's manager tried to pull Cooper back through the curtains.

It was decided to continue with the show. Dustin Gee and Les Dennis were the act that had to follow Cooper, and other stars proceeded to present their acts in the limited space in front of the stage. While the show continued efforts were being made backstage to revive Cooper, not made any easier by the darkness. It was not until a second commercial break that paramedics moved his body to Westminster Hospital, where he was pronounced dead on arrival. His death was not officially reported until the next morning, although the incident was the leading item on the news programme that followed the show. Cooper was cremated at Mortlake Crematorium in London.[19][20]

The video of Tommy Cooper suffering the fatal heart attack on stage has been uploaded to numerous video sharing websites. YouTube drew criticism from a number of sources when footage of the incident was posted on the website in May 2009. John Beyer of the pressure group Mediawatch-UK said: "This is very poor taste. That the broadcasters have not repeated the incident shows they have a respect for him and I think that ought to apply also on YouTube."[18]

On 28 December 2011 segments of the Live From Her Majesty's clip, including Cooper collapsing on stage, were included in the Channel 4 programme The Untold Tommy Cooper.

Personal life

Cooper married Gwen Henty in Nicosia, Cyprus, on 24 February 1947. She died in 2002.[21] They had two children: Thomas, who was born in 1956, became an actor under the name Thomas Henty and died in 1988; and Victoria.

From 1967 until his death Cooper also had a relationship with his personal assistant, Mary Fieldhouse, who wrote about it in her book, For the Love of Tommy (1986).[22]

Cooper's will was proved via probate on 29 August 1984, at £327,272.[23]

On Christmas Day 2018 the documentary Tommy Cooper: In His Own Words was broadcast on Channel 5. The programme featured Cooper's daughter Vicky, who gave her first television interview following years of abstaining "because of the grief".[24]

Legacy and honours

A statue of Cooper was unveiled in his birthplace, Caerphilly, in 2008 by Sir Anthony Hopkins, who is patron of the Tommy Cooper Society.[25] The statue, which cost £45,000, was sculpted by James Done.[26] In 2009, for Red Nose Day, a charity Red Nose was put on the statue, but the nose was stolen.[27] Hip-hop duo Dan le Sac Vs Scroobius Pip wrote the song "Tommy C", about Cooper's career and death, which appears on their 2008 album, Angles.

Cooper was a member of the Grand Order of Water Rats.[28]

In a 2005 poll, The Comedians' Comedian, comedians and comedy insiders voted Cooper the sixth greatest comedy act ever.[29] He has been cited as an influence by Jason Manford[30] and John Lydon.[31] Jerome Flynn has toured with his own tribute show to Cooper called Just Like That.

In February 2007 The Independent reported that Andy Harries, a producer of The Queen, was working on a dramatisation of the last week of Tommy Cooper's life.[32] Harries described Cooper's death as "extraordinary" in that the whole thing was broadcast live on national television.[33] The film subsequently went into production over six years later as a television drama for ITV. From a screenplay by Simon Nye, Tommy Cooper: Not Like That, Like This was directed by Benjamin Caron and the title role was played by David Threlfall. It was broadcast 21 April 2014.[34]

In 2010 Cooper was portrayed by Clive Mantle in a stage show, Jus' Like That! A Night Out with Tommy Cooper, at the Edinburgh Festival. To train for the role Mantle mastered many of Cooper's magic tricks, studying under Geoffrey Durham for several months.[35]

In 2012 the British Heart Foundation ran a series of advertisements featuring Tommy Cooper to raise awareness of heart conditions. These included posters bearing his image together with radio commercials featuring classic Cooper jokes.[36]

Being Tommy Cooper, a new play written by Tom Green and starring Damian Williams, was produced by Franklin Productions and toured the UK in 2013.[37][38]

In 2014, with the support of The Tommy Cooper Estate and Cooper's daughter Victoria, a new tribute show, Just Like That! The Tommy Cooper Show, commemorating 30 years since the comedian's death was produced by Hambledon Productions. The production moved to the Museum of Comedy in Bloomsbury, London, from September 2014 and continues to tour extensively throughout the UK.[39][40]

In May 2016 a blue plaque in memory of Cooper was unveiled at his former home in Barrowgate Road, Chiswick. In August it was announced that the Victoria and Albert Museum had acquired 116 boxes of Cooper's papers and props, including his "gag file", in which the museum said he had used a system to store his jokes alphabetically "with the meticulousness of an archivist".[41]

Recordings

- "Don't Jump Off the Roof Dad" (1961), words and music by Cy Coben, single, Palette Records PG 9019 (reached Number 40 in the UK Singles Chart)[42]

- "Ginger" – 7" single

- "Happy Tommy" – 7" single

- "Just Like That" 7" single

- "Masters of Comedy" – CD

- "No Arms Will Ever Hold You" – 7" single

- "Sweet Words of Love" – 7" single

- "Tommy Cooper Very Best Of" – CD, DVD

- "Walkin' Home From School" – 7" single

- "We'll Meet Again" – 7" single

UK VHS/DVD releases

| VHS title | Release date |

|---|---|

| A Tribute to Tommy Cooper (TV9936) | 3 November 1986 |

| The Magic of Tommy Cooper - Tribute to a Comedy Genius (TV8091) | 4 June 1990 |

| The Best of Tommy Cooper (TV8141) | 19 August 1991 |

| Tommy Cooper - "Not Like That" (TV8160) | 1 June 1992 |

| Tommy Cooper - Solid Gold (TV8169) | 5 October 1992 |

| The Magic of Tommy Cooper - Tribute to a Comedy Genius (LC0012) | 1 March 1993 |

| The Magic Lives of Tommy Cooper (TV8182) | 11 October 1993 |

| Tommy Cooper - The Magic Touch (TV8184) | 7 March 1994 |

| The Very Best of Tommy Cooper (TV8198) | 6 March 1995 |

| Tommy Cooper - The Missing Pieces (TV8211) | 2 October 1995 |

| The Feztastic Tommy Cooper | 6 May 1996 |

| Tommy Cooper - The Golden Years (TV8261) | 3 November 1997 |

| A Feztival Of Fun With Tommy Cooper (B00005M1YE) | 16 September 2002 |

References

- Cavendish, Dominic (4 April 2003). "Just like Tommy". Retrieved 12 January 2019 – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- "Obituary: Tommy Cooper". The Times. 17 April 1984.

- "Tommy Cooper", www.exetermemories.co.uk, archived from the original on 12 January 2012

- GRO Register of Marriages: Dec 1919 11a 1538 Pontypridd – Thomas H. Cooper = Gertrude C. Wright.

- "Home". BBC News. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- "Tommy Cooper – Biography". Biographyonline.net. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- GRO Register of Births: Se 1930 5b 60 St Thomas – David J. Cooper, mmn – Wright

- "BBC - Error 404 : Not Found". Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- "h2g2 - Tommy Cooper - Just Like That - Edited Entry". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- Logan, Brian (5 December 2016). "Just like hat! Why Tommy Cooper's fez was much more than a prop". the Guardian. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- Roy Busby. British Music Hall: An Illustrated Who's Who from 1850 to the Present Day. ISBN 023640053-3.

- John Fisher, Tommy Cooper: Always Leave Them Laughing, Harper Collins, 2006, p. 137

- tweet_btn(), Phil Strongman 25 May 2015 at 14:00. "Will Hay: Britain's bumbling star of the screen and skies". www.theregister.co.uk. Retrieved 27 December 2018.

- Fisher, Tommy Cooper, pp. 157–158

- "BBC Two - The Art of Tommy Cooper". Bbc.co.uk. 20 April 2014. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- "The secret life of Tommy Cooper". The Independent. 24 September 2006. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- Nathan Bevan (12 April 2009). "Tommy Cooper's last act fooled us all, says Jimmy Tarbuck". Wales on Sunday.

- Kelly Miles (10 May 2009). "Tommy Cooper death video posted on YouTube". Wales on Sunday.

- "Mortlake Crematorium Celebrates 75 Years". Lodge Brothers - Funeral Directors. Retrieved 22 July 2018.

- Dyduch, Amy (7 June 2014). "Mortlake Crematorium marks 75 years". Richond and Twickenham Times.

- Marc Brodie. Cooper, Thomas Frederick [Tommy] (1921–1984). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- Fieldhouse, Mary (1986). For the Love of Tommy. London: Robson Books Ltd. ISBN 978-0860513872.

- Court of Great Lambeth Law England and Wales (CGPLA)

- "Tommy Cooper: Star's daughter breaks silence 34 YEARS after his death". Express.co.uk. 24 December 2018. Retrieved 27 December 2018.

- "Tommy Cooper - Almost a Magician - Statue". tommycooper.homesteadcloud.com. Archived from the original on 27 December 2018. Retrieved 27 December 2018.

- "Tommy Cooper statue is unveiled". BBC News. 23 February 2008. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- Rhys, Steffan. "Tommy Cooper statue's red nose gone just like that". Wales News. WalesOnline. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- "Roll of Honour". Grand Order of Water Rats. 17 April 2017.

- "Cook Tops Poll of Comedy Greats". 2 January 2005. Retrieved 10 April 2017.

- WalesOnline. "I thought about retraining as a plasterer, says ex-One Show presenter Jason Manford". Walesonline.co.uk. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- "Metal box, P.I.L". Observer.guardian.co.uk. 11 February 2011. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- Akbar, Arifa; Brown, Jonathan (8 May 2007). "Just like that! Tommy Cooper's final days". The Independent. London. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- Harries, Andy (27 April 2007). Andy Harries, Coventry Conversations, 25 April. Coventry University Pod-casting Service. Archived from the original (MP3) on 13 July 2012. Retrieved 2 March 2008.

- Nissim, Mayer (23 May 2013). "'Shameless' David Threlfall to play Tommy Cooper in one-off ITV drama". Digital Spy. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- "Jus' like that! Legendary Welsh-born comic Tommy Cooper is the subject of a new stage show starring actor Clive Mantle. He tells James Rampton what it's like to play such an iconic figure: Went to the paper shop – it had blown away". South Wales Echo , accessed via Questia Online Library. 13 April 2010. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- Parsons, Russell (1 June 2012). "BHF uses Tommy Cooper in latest ads". Marketing Week. Centaur Media Plc. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- "Being Tommy Cooper". Franklin Productions Ltd. Archived from the original on 9 April 2013. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- "Tommy Cooper" (PDF). TOMMY COOPER: NOT LIKE THAT, LIKE THIS. UK: ITV. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- "Lincolnshire-based professional theatre company". Hambledon Productions. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- "Home". Museum of Comedy. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- "Tommy Cooper's 'gag file' to be preserved by Victoria & Albert museum". BBC News. 26 August 2016.

- Roberts, David (2006). British Hit Singles & Albums (19th ed.). London: Guinness World Records Limited. p. 120. ISBN 1-904994-10-5.

Sources

- Fieldhouse, Mary (1986). For the Love of Tommy: a personal portrait of Tommy Cooper.

- Fisher, John (1973). Funny way to be a hero.

- Cooper, Tommy (1994). Just Like That (3rd ed.).

- Nathan, David (1971). The laughtermakers: a quest for comedy.

- Vahimagi, Tise (1996). British Television, an illustrated guide (2nd ed.).

External links

- Tommy Cooper - Almost a Magician - archived link