Tom Thumb (play)

Tom Thumb is a play written by Henry Fielding as an addition to The Author's Farce. It was added on 24 April 1730 at Haymarket. It is a low tragedy about a character who is small in both size and status who is granted the hand of a princess in marriage. This infuriates the queen and a member of the court and the play chronicles their attempts to ruin the marriage.

The play incorporated part of the satire in The Author's Farce and also was a farce because the tragedies in the play became absurd. Additionally, Fielding explored many issues with gender roles through his portrayals of characters. Critics largely enjoyed the play and noted its success through comedy. As the play later was edited to become the Tragedy of Tragedies, critics like Alberto Rivero noted its impact on Fielding's later plays.

Background

Tom Thumb was added to the ninth showing of The Author's Farce that took place on 24 April 1730. Together, the shows lasted at the Haymarket until they were replaced by Fielding's next production, Rape upon Rape. They later were revived together on 3 July 1730 for one night. Tom Thumb was also included with other productions, including Rape upon Rape for 1 July 1730, and was incorporated into the Haymarket company's shows outside of the theatre on 4 and 14 September 1730 at various fairs. It was later turned into the Tragedy of Tragedies.[1]

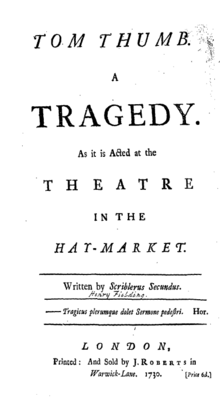

When the play was no longer featured alongside of The Author's Farce, the satire becomes less evident. To combat this problem, Fielding added other components, including footnotes, prefaces, and prologues, to the second edition of the written version.[2] This is another component that Tom Thumb shares with The Tragedy of Tragedies, and an aspect common to Fielding's so-called 'Scriblerus plays', which incorporate the use of H. Scriblerus Secundus as a pen name for the print editions.[3]

A revised edition of the play was published with a few alterations, including adding two scenes, Prologue, Epilogue, and Preface. Another revision came on 30 November 1730 and added another act to follow Act II, Scene 9. This act attacked Colley Cibber's recent appointment as the Poet Laureate. The new Act, titled The Battle of the Poets, or, The Contention for the Laurel, was published on its on 17 December 1730. However, this act was not Henry Fielding's; it is attributed to Thomas Cooke but authorship was never proven.[4]

Cast

Cast according to the printed billing:[5]

- Tom Thumb – played by Miss Jones

- King Arthur – played by Mr. Mullart

- Princess Huncamunca – King Arthur's daughter, played by Mrs. Jones

- Queen Dollalolla – King Arthur's wife, played by Mrs. Mullart

- Lord Grizzle – played by Mr. Jones

- Mr. Doodle – played by Mr. Marshall

- Mr. Noodle – played by Mr. Reynolds

- 1st Physician – played by Mr. Hallam

- 2nd Physician – played by Mr. Dove

- Cleora – played by Mrs. Smith

- Mustacha – played by Mrs. Clark

- Other characters include Courtiers, Slaves, Bailiffs and others.

- Prologue spoken by Mr. Jones[6]

- Epilogue spoken by Miss Jones[7]

Plot

Fielding, writing as Scriblerus Secondus, prefaces the play by explaining his choice of Tom Thumb as his subject:

It is with great Concern that I have observed several of our (the Grubstreet) Tragical Writers, to Celebrate in their Immortal Lines the Actions of Heroes recorded in Historians and Poets, such as Homer or Virgil, Livy or Plutarch, the Propagation of whose Works is so apparently against the Interest of our Society; when the Romances, Novels, and Histories vulgo call'd Story-Books, of our own People, furnish such abundance and proper Themes for their Pens, such are Tom Tram, Hickathrift &c.[8]

Fielding reverses the tragic plot by focusing on a character who is small in both size and status. The play is a low tragedy that describes Tom Thumb arriving at King Arthur's court showing off giants that he defeated. As a reward, Arthur grants Tom the hand of princess Huncamunca, which upsets both his wife, Dollalolla, and a member of the court, Grizzle. The two plot together to ruin the marriage, which begins the tragedy.[9] Part way through the play, two doctors begin to discuss the death of Tom Thumb and resort to using fanciful medical terminology and quoting ancient medical works with which they are not familiar. However, it becomes apparent that it was not Tom who died, but a monkey.[10] The tragedy becomes farcical when Tom is devoured by a cow. This is not the end of Tom, because his ghost later suffers a second death at the hands of Grizzle.[11] Then, one by one, the other characters farcically kill each other, leaving only the king at the end to kill himself.[12]

Themes

Tom Thumb incorporates part of the satire found within The Author's Farce: the mocking of the heroic tragedy that has little substance beyond dramatic cliche. The satire originates in a play within The Author's Farce in which the character Goddess of Nonsense selects from various manifestations of bad art; of the manifestations, Don Tragedio is the one selected as the basis for the satire within Tom Thumb. Fielding, in following the "Don Tragedio" style, creates a play that denies the tradition and seeks newness within theatre only for newness's sake, regardless of the logical absurdities that result.[13] In Tom Thumb and Tragedy of Tragedies, Fielding emphasises abuses of the English language in his character's dialogues, by removing meaning or adding fake words to the dialogue, to mimic and mock the dialogues of Colley Cibber's plays.[14]

The satire of Tom Thumb reveals that the problem with contemporary tragedy is its unconscious mixture of farcical elements. This results from the tragedians lacking a connection to the tradition of tragedy and their incorporation of absurd details or fanciful elements that remove any realism within the plot. It is also possible that some of these tragedians clung to the tradition in a way that caused them to distort many of the elements, which result in farcical plots. These tragedies become humorous because of their absurdities, and Tom Thumb pokes fun at such tragedies while becoming one itself. The satire of the play can also be interpreted as a deconstruction of tragedy in general. Fielding accomplishes the breaking down and exposing of the flaws of Tragedy through showing that the genre is already breaking down itself. However, Fielding's purpose in revealing the breakdown is to encourage the reversal of it.[15]

Besides critiquing various theatrical traditions, there are gender implications of the dispute between King Arthur and his wife, Queen Dollalolla, over which of the females should have Tom as their own. There are parallels between King Arthur with King George and Queen Dollalolla with Queen Caroline, especially with a popular belief that Queen Caroline controlled the decisions of King George. The gender roles were further complicated and reversed by the masculine Tom Thumb being portrayed by a female during many of the shows. This reversal allows Fielding to critique the traditional understanding of a hero within tragedy and gender roles in general. Ultimately, gender was a way to comment on economics, literature, politics, and society as a whole.[16]

Response

Jonathan Swift, when witnessing the death of Tom's ghost, was reported in the memoirs of Mrs. Pilkington to have laughed out loud; such a feat was rare for Swift and this was only the second time such an occurrence was said to have happened.[17] J. Paul Hunter argues that the whole play "depends primarily on one joke", which is the diminutive size of the main character.[18] F. Homes Dudden characterises the play as "a merry burlesque" and points out that the play was "a huge success".[19] Albert Rivero points out that the ignoring of Tom Thumb for its expanded and transformed version, Tragedy of Tragedies, "is a regrettable oversight because Tom Thumb constitutes a vital link in Fielding's dramatic career, its importance lying not so much in its later expansion into Scriblerian complexity as in its debt to, and departure from, the play it followed on stage for thirty-three nights in 1730."[20]

Notes

- Rivero 1989 p. 53

- Rivero 1989 p. 57

- Rivero 1989 p. 75

- Dudden 1966 pp. 58–59

- Fielding 2004 p. 385

- Fielding 2004 p. 381

- Fielding 2004 p. 383

- Fielding 1970 p. 18

- Rivero 1989 pp. 61–62

- Rivero 1989 p. 69

- Rivero 1989 p. 63

- TOM THUMB, A TRAGEDY by HENRY FIELDING, Rochester University Library

- Rivero 1989 pp. 54–55

- Rivero 1989 p. 63

- Rivero 1989 pp. 55–58

- Campbell 1995 pp. 19–20

- Hillhouse 1918 note p. 150

- Hunter 1975 p. 23

- Dudden 1966 pp. 56–57

- Rivero 1989 pp. 53–54

References

- Campbell, Jill. Natural Masques: Gender and Identity in Fielding's Plays and Novels. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1995.

- Dudden, F. Homes. Henry Fielding: his Life, Works and Times. Hamden, Conn.: Archon Books, 1966.

- Fielding, Henry. Ed. L. J. Morrissey. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1970.

- Fielding, Henry. Plays Vol. 1 (1728–1731). Ed. Thomas Lockwood. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2004.

- Hillhouse, James Theodore (ed.). The Tragedy of Tragedies; or, The Life and Death of Tom Thumb the Great. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1918.

- Hunter, J. Paul. Occasional Form: Henry Fielding and the Chains of Circumstance. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1975.

- Rivero, Albert. The Plays of Henry Fielding: A Critical Study of His Dramatic Career. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1989.