Actor Rebellion of 1733

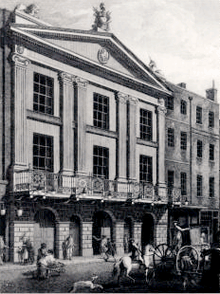

The Actor Rebellion of 1733 was an event that took place at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane in London, England, when the actors who worked there, disapproving of the changes in the management, attempted to seize control. Before the rebellion, the theatre was controlled by the managers Theophilus Cibber, John Ellys, and John Highmore. When Theophilus lost his share and was denied a bid to run the theatre, he, along with other actors, attempted to take over the theatre by controlling the lease. When the shareholders found out, they refused to admit the actors to the building and the theatre was closed for several months. The fight spilled over to the contemporary newspapers, which generally sided with the managers.

The Theatre Royal reopened on 24 September 1733 with a new company of actors, though they were less experienced and talented than the old crew. The majority of old actors moved to the Little Theatre, Haymarket, though a few remained loyal. Henry Fielding sided with the managers and produced several plays to aid the Theatre Royal, though this caused a backlash when the rebelling actors finally won the dispute. By the end of 1733, the rebellious actors managed to seize legal control of the theatre's property and Highmore, the sole manager of the Theatre Royal at the time, lost all legal abilities to stop them. By February 1734, he sold his shares to Charles Fleetwood who then made an agreement with the actors that secured their return.

Background

The Theatre Royal, Drury Lane was run by the holders of one of the two official licenses, or letters patent, established by Charles II in 1660. It was operated by Christopher Rich from 1693 until 1714. He was replaced after his death by three actors, Colley Cibber, Thomas Doggett, and Robert Wilks. After Doggett died, Barton Booth took over his share.[1] In 1730, a notice in the Daily Journal stated that a patent would be issued to Booth, Cibber, and Wilks authorising the official government license to run the Theatre Royal. After bureaucratic delays, the official patent was given to the three managers only in 1732 that was to last for 21 years. On 13 July 1732, Booth, in poor health, decided to sell half of his share to Highmore, a fellow actor and a socialite. On 27 September, Wilks died and his share was inherited by his widow, who then authorised Ellys, a painter, to serve in her place. In reaction to the changing partners, Colley Cibber rented his share to his son Theophilus, an actor.[2]

The new management group had two members, Highmore and Ellys, who were incompetent and Theophilus Cibber was known to be both arrogant and volatile.[3] By the end of 1732, there were problems with the management of the theatre, which resulted in the failure of Charles Johnson's Caelia: or, The Perjured Lover on 4 December. The 8 March 1733 Grub-Street Journal seized on the event and used the failure to criticise the theatre's management:[4] "how insufficient the present managers of Drury-lane playhouse are to discharge their trust, as directors of our public entertainments."[5] The newspaper was not the only group concerned and many plays were soon cancelled.[6]

Matters were complicated by mass illnesses spreading across London; the epidemic, probably flu, reduced the number of actors able to work and many plays were cancelled. Even Henry Fielding's play The Miser, which was to open early January, was postponed because of the poor health of its cast members, including Theophilus. The Miser was eventually staged in mid February and was successful, but another of his plays, Deborah: or, a Wife for You All, lasted only one night on 6 April 1733. Regardless of the problems plaguing the season, it was positive for Fielding while it lasted, with six of his plays being produced on stage along with Thomas Arne's The Opera of Operas, Fielding's Tom Thumb set to music.[7]

Management changes

Highmore and Ellys, both gentlemen and not actors, insisted on actively participating in every day-to-day decisions regarding scheduling, choice of plays, expenses, actors' behaviour.[8] Their management style clashed with Theophilus, when he recovered and returned in February. They denied his play The Harlot's Progress instead putting a play by Ellys. The fighting between the managers coincided with poor attendance from both the epidemic in London and other theatres attracting audiences with popular operatic performances. Theophilus's play The Mock-Officer failed, which caused Highmore and Ellys to turn further against him. However, his 31 March 1733 The Harlot's Progress, based on William Hogarth's painting of the same name, proved to be very successful and embarrassed the two other managers.[9]

While Theophilus Cibber was disputing with Highmore and Ellys, Aaron Hill became interested in partnering at the Theatre Royal. Hill was earlier a partner at the theatre until he was removed during a previous actor riot that took place in June 1710. On 22 March 1733, Hill, in a letter to Benjamin Victor, a dramatist who had arranged the sale of Booth's shares to Highmore,[10] criticised the fact that he was kept from buying into the theatre's management and attacked Theophilus. He offered 900 pounds for three years for Booth's shares and 1800 pounds for Mary Wilks's shares. Negotiations continued until May when they were dropped.[11] Hester Booth, widow of Barton Booth, sold her remaining shares to Henry Giffard, the manager of Goodman's Fields Theatre, just few days after her husband died on 10 May.[12]

By this time, many of the partners, including Wilks, Ellys, and Colley Cibber, no longer wanted to be a part of the theatre and sought to sell their shares. When Colley sought to rent out his share to his son for 300 pounds a year, Highmore approached Colley in order to buy. News of Colley's selling of the shares to Highmore first appeared in the Daily Post of 27 March 1733. The sale price was around 3000 guineas and 3500 pounds. Theophilus was upset that his father sold the share to Highmore instead of continuing to rent it out to himself.[13] The share, as Theophilus believed, was his "Birthright".[14]

Rebellion

Theophilus first tried to work with Highmore and asked to run the operations of the theatre. However, he was turned down, which provoked him to stir the actors into a rebellion.[15] Many of the actors were upset about the management changes and theatre's operations. Highmore did not have experience in theatre, refused to listen to actors' ideas, and cut their salaries in half.[12] Theophilus was known as a successful manager and a good actor. The rebellious actors' plan was to take over the lease and then deny the use of the building to the shareholders, who did not own the complex that they set their stage in. The actors would then use their control over the building to negotiate renting of the patent so they could control how the theatre was run.[15]

When the actors tried to rent the building, the remaining shareholders found out about it. They responded by refusing admittance to the actors. The building was shut down and no plays were performed.[16] According to the Daily Post of 29 May 1733:

the Occasion we are inform'd was, that at Midnight on Saturday last several Persons arm'd took Possession of the same, by Direction from some of the Patentees, and lock'd up and barricado'd all the Doors and Entrances thereunto, against the whole Company of his Majesty's Comedians, as also against Mr. Cibber, jun. notwithstanding he had paid to one of the Patentees several Hundred Pounds for one third Part of the Patent, Cloaths, Scenes, &c. and all Rights and Privileges thereunto annexed, for a certain Term not yet expired.[17]

The actors petitioned Charles FitzRoy, 2nd Duke of Grafton, the Lord Chamberlain, and requested that he settle the dispute, but he refused to involve himself in the matter. By early June, the actors had control of the theatre through the lease, but the management refused to leave. The actors tried to file for the management to be legally removed from the property, but the court system was slow to respond.[16]

The management continued to cause problems for various actors, including Benjamin Griffin. Griffin was fired from the theatre on 4 June 1733.[18] He responded in the Daily Post on 11 June 1733 with a history of the events since he first started in 1721 until his removal. He accused the management of bad treatment and wrote:[19]

I could give the Publick a great many Instances of the Gentlemen's Mismanagement and of Injuries done to the Company this Season in their Direction. But when I affirm that they have no Experience, no Knowledge, no Capacity, For Gathering together, Forming, Entertaining, Governing, Privileging, and Keeping a Company of Comedians ... more than the being able to purchase the Patent [...] it is a Truth that if any one does not now believe, I am positive that they will in a very little Time be thoroughly convinced of.[20]

Contemporary response

Many of the local newspapers were quick to respond to the rebellion. An article in The Craftsman dated 2 June 1733 described the actors as "malecontent Players" who were busy in mutiny. On 7 June, the Grub-Street Journal stated, in an article by Musaeus, that Theophilus was selfish. Another article in the Grub-Street Journal, by Philo Dramaticus, attacked the management for not understanding how theatres are supposed to work. The managers were the first to state their defence and argued that everything they did was correct and that the actors had no reason to complain, especially over the treatment that they received.[21]

The actors responded later in June with A Letter from Theophilus Cibber, Commedian, To John Highmore, Esq. Within the response, Theophilus Cibber emphasised the inability of the management to effectively run the theatre, claimed that they were acting like tyrants, and alleged that they unjustly refused the offer by the actors to rent out the patent. This did not calm the dispute; instead, the Grub-Street Journal of 14 June 1733 printed parts of John Vanbrugh's Aesop, a play that criticised the actor rebellion that took place in 1695. On 26 June, the Grub-Street Journal in an article by Musaeus claimed that many of the problems that the actors complained about were caused by previous managers, who were also actors, and not by the current management that was composed of outsiders. Additionally, Musaeus claimed that actors in general were unfit to run the theatre.[22]

A pamphlet titled An Impartial State of the Present Dispute Between the Patent and Players was published during the late summer that attacked the actors. It claimed that "all Men of Sense and Integrity seem to be entirely convinced that the Patentees of the Theatre-Royal in Drury-Lane, have had great Injustice done them by the late Attempt of Part of their own Company to defraud them of their Property".[23] The actors responded in an article published in the Daily Journal of 26 September. Also during the summer, Edward Phillips produced The Stage-Mutineers, a play that started on 27 July and ran for twelve nights. The play made fun of actors, writers, and the management as a whole. Even though it was attacked in the Grub-Street Journal of 9 August, theatre historian Robert Hume described the play as "harmless stuff".[24] Regardless, Fielding was personally mocked as Crambo, one of the characters within the play, and was offended by the portrayal.[25]

Reopening

The Theatre Royal reopened on 24 September 1733 with a new company of actors. The majority of the rebellious actors joined the Little Theatre in Haymarket and started producing plays on 26 September. Although the Theatre Royal had replacement actors of a lesser talent and a few loyal experienced members, Henry Fielding joined the management's side of the dispute. Of the 15 loyal actors that stayed with the Theatre Royal, only a few, including Kitty Clive, Christiana Horton, William Mullart, and Charles Stoppelaer, were of note.[26] Reportedly, Highmore was losing 50–60 pounds a week.[27] Victor, in his account of the time, wrote:

In this maimed Condition the Business of Course went lamely on; for a very middling Company of Players could be expected to bring but thin losing Audiences, especially while Party prevailed, and those very Plays were acted much better in the Haymarket. The unavoidable and melancholy Consequence of this Proceeding was, that there was a Ballance every Saturday Morning in the Office against the Manager, of Fifty or Sixty Pounds; and his Pride, as well as his Honour, were too nearly concerned not to prudence the Deficiency every Week with the utmost Exactness.[28]

In such conditions, Giffard sold his shares and turned over full control of the theatre to Highmore. Hill was brought in to work with the actors at Drury Lane by Autumn 1733, but the theatre was still declining by the end of the year.[29]

In order to aid the theatre, Fielding revised his The Author's Farce and The Intriguing Chambermaid.[30] Fielding's The Miser was also put on 27 October 1733 with the King, the Queen, and many noble families in attendance. After this, Fielding produced The Universal Gallant: or, The Different Husbands, which didn't run until February 1735.[31] 20th-century theatre scholar Charles Woods believed that Fielding joined with the management of the Theatre Royal because they were "people whose legitimate investments were being jeopardized".[32] Fielding later attacked Theophilus in a revised version of his The Author's Farce which ran on 15 January 1734. This caused a backlash upon him after the rebelling actors finally won in the dispute, and it was harder for him to stage plays.[33]

Theophilus, through his father, applied to the Lord Chamberlain during the summer asking to have a new license issued, but he was refused. Following this, he applied to Charles Lee, the Master of the Revels, and received a license to perform theatrical shows in return for payment even though the license had no legal authority. This brought about criticism against Lee in the Daily Post dated 29 September 1733 over issuing the licence and called it just a ploy by the actors. On 30 October, the management of the Theatre Royal sent a letter to veteran actor John Mills and other rebels threatening further legal action regarding their unlicensed theatre. After Theophilus responded with a claim that he was acting within the law, the management and John Rich, manager of the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden, demanded the courts to shut down the unlicensed theatres. A 5 November hearing set a date for a trial, but the case fell apart before it was ever heard over the technical wording of a law that conflicted with the original request by the licensed theatre managers.[34]

A trial, in which the rebellious actors sued the management at the King's Bench over the management's occupation of the building that the actors controlled the lease, was held on 12 November. The judgment under Chief Justice Philip Yorke was in favour of the actors, and they were to be granted control of the theatre building in March 1734. Highmore, in response, asked for a charge against John Harper, one of the rebellious actors, for being a vagrant, and Harper was sent to Bridewell Palace prison. This provoked a negative reaction by the public, and the action was attacked in the Daily Post of 16 November. Eventually, a writ of habeas corpus was issued on 20 November and he was released without a case tried against him. Having no other recourse, Highmore began to negotiate the sale of the theatre license. Charles Fleetwood purchased both Highmore and Wilks's portions of the license on 24 January 1734. On 2 February, the Daily Courant announced that Fleetwood asked for the rebellious actors to return. An agreement was reached for higher wages and promotion of Theophilus to a deputy manager of the theatre. The actors took control of the Theatre Royal on 8 March 1734, marking the end of the rebellion.[35]

Notes

- Styan 1996 p. 274

- Hume 1988 pp. 142–144

- Hume 1988 pp. 144

- Battestin and Battestin 1993 pp. 162–163

- Battestin and Battestin 1993 qtd. p. 163

- Battestin and Battestin 1993 p. 163

- Battestin and Battestin 1993 pp. 163–167

- Koon 1986 p. 132

- Shevelow 2005 pp. 157–159

- Koon 1986 p. 131

- Hume 1988 pp. 155–156

- Koon 1986 p. 134

- Hume 1988 pp. 156–157

- Battestin and Battestin 1993 qtd p. 167

- Hume 1988 p. 157

- Hume 1988 p. 158

- Hume 1988 qtd. p. 158

- Shevelow 2006 p. 165

- Hume 1988 p. 161

- Hume 1988 qtd. p. 161

- Hume 1988 p. 159

- Hume 1988 pp. 159–162

- Hume 1988 qtd p. 162

- Hume 1988 p. 162

- Battestin and Battestin 1993 p. 168

- Hume 1988 pp. 164–166

- Koon 1986 p. 135

- Victor 1761 p. 19

- Hume 1988 pp. 166–168

- Hume 1988 p. 169

- Battestin and Battestin 1993 pp. 168–169

- Woods 1966 p. xiv

- Hume 1988 p. 165

- Hume 1988 pp. 173–176

- Hume 1988 pp. 176–180

References

- Battestin, Martin, and Battestin, Ruthe. Henry Fielding: a Life. London: Routledge, 1993. ISBN 0-415-01438-7

- Hume, Robert. Fielding and the London Theater. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988. ISBN 0-19-812864-9

- Koon, Helene. Colley Cibber: A Biography. University Press of Kentucky, 1986. ISBN 0-8131-1551-5

- Shevelow, Kathryn. Charlotte. New York: H. Hold, 2005. ISBN 0-8050-7314-0

- Shevelow, Kathryn. Charlotte. MacMillan, 2006. ISBN 0-312-42576-7

- Styan, J. L. The English Stage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-521-55398-9

- Victor, Benjamin. The History of the Theatres of London and Dublin. London: 1761. OCLC 29252424

- Woods, Charles. "Introduction" in The Author's Farce. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1966. OCLC 355476