The Lottery (play)

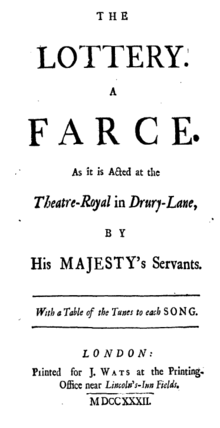

The Lottery is a play by Henry Fielding and was a companion piece to Joseph Addison's Cato. As a ballad opera, it contained 19 songs and was a collaboration with Mr Seedo, a musician. It first ran on 1 January 1732 at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. The play tells the story of a man in love with a girl. She claims she has won a lottery, however, making another man pursue her for the fortune and forcing her original suitor to pay off the other for her hand in marriage, though she does not win.

The Lottery mocks the excitement of the lottery and those who sell, rent, or purchase tickets. It was highly successful and set the tone for Fielding's later ballad operas. The play was altered on 1 February 1732 and this revised edition was seen as a great improvement.

Background

After Fielding returned to work for the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, he wrote The Lottery. It was a companion piece, in the form of ballad opera, that first ran on 1 January 1732 alongside of Addison's Cato. The piece contained 19 songs and was a collaboration with "Mr Seedo", a musician.[1] It is uncertain as to when Seedo first started working with Fielding, but he may have started with Fielding during 1730 at the Little Haymarket theatre.[2]

The play was successful and was performed 15 times during January. Fielding altered the play on 1 February 1732 by removing four songs and adding seven midway through the play. The revised form ran for 14 more nights during that season and was put on each year until 1740 and occasionally thereafter until 1783.[3] The play was published 7 January 1732 by Watts.[4]

Cast

Cast of characters:[5]

- Lovemore – Charles Stoppelar

- Chloe – played by Kitty Clive

- Jack Stocks – played by Theophilus Cibber

- Ticket Renter – played by John Harper

Plot

Fielding's prologue begins with his definition of various genres and his understanding of "Farce", even though many of his works are more ballad opera than actual farce:[6]

- As Tragedy prescribes to Passion Rules,

- So Comedy delights to punish Fools;

- And while at nobler Game she boldly flies,

- Farce challenges the Vulgar as her Prize.

- Some Follies scarce perceptible appear

- In that just Glass, which shews you as you are.

- But Farce still claims a magnifying Right,

- To raise the Object larger to the Sight,

- And shew her Insect Fools in stronger Light.

Lovemore loves a girl named Chloe. Instead of accepting him as a suitor, Chloe travels into London with the hope that she will win a 10,000 pound lottery prize.[7] She convinces herself so much of this fate that she begins to boast of having a fortune already. Jack Stocks, a man wanting that fortune, takes on the identity of Lord Lace and seeks her in marriage. It is revealed that the ticket was not a winner. Lovemore, a man who has romantically pursued her through the play, offers Stocks 1,000 pounds for Chloe's hand, and the deal is made.[3]

In the revised edition of the play, more characters are added who desire to win the lottery and there is a stronger connection made between Chloe and Lovemore.[3] The revised version ends with Jack, her husband at the time, being paid off to no longer have claim to Chloe as his wife even though everyone knows that she did not win.[7]

Themes

The Lottery pokes fun at the excitement surrounding the lottery held during the fall of 1731. In particular, Fielding mocks both those who sell or rent tickets and those who purchase the tickets.[3] The portrayal of the ticket vendors emphasised the potential for deceit and the amount of scams that were possible. It also attacked how the vendors interacted with each other in a competitive spirit.[8] Fielding expects that his audience understands how the lottery operated and focused on how gambling cannot benefit gamblers.[7]

Others, such as Hogarth in The Lottery (1724), rely on similar images of Fortune as in Fielding's plays. However, Fielding differs from Hogarth by adding a happy ending to the portrayal of the lottery system.[9] This was not the only time Fielding relies on the lottery system; he also includes ticket vendors in his play Miss Lucy in Town and in his novel Tom Jones.[10]

Sources

The lottery that the play is directly connected to took place during November–December 1731. It was part of the State Lottery that was in place since 1694. The system continued to be lucrative for the British Parliament over the 18th-century. The system in place during 1731 consisted of 80,000 tickets sold with only 8,000 connected to prizes. The top prize, of which there were two available, was 10,000 pounds. The drawing of the numbers lasted for forty days and consisted of numbers being picked from a large container that are then determined as either a winner or a "blank", which means that no prize would be received. This lottery system came under fire because, it was argued, they promoted gambling and took advantage of people. Problems grew worse when second hand vendors began to sell the tickets at high prices.[11]

Response

The play was a success and earned Fielding a great deal of money.[12] F. Homes Dudden believed that "The Lottery, with its well-drawn leading character, its clever little songs, and its humorous yet biting criticism of lottery abuses, scored an immediate success, and, indeed, for many years continued to be a favourite with the public."[13] Edgar Roberts emphasises the importance of The Lottery as the play that "set the pattern for his ballad operas during the next three years at Drury Lane: happy, lightly satirical, and for the most part nonpolitical."[14] Robert Hume believes that the play was a "rollicking little ballad" and that the revised version "is a major improvement".[15]

Notes

- Hume 1988 pp. 118–119

- Roberts 1966 pp. 179–190

- Hume 1988 pp. 119–120

- Paulson 2000 p. 35

- Hume 1988 p. 199

- Battestin and Battestin 1993 p. 106

- Pagliaro 1998 p. 81

- Dudden 1966 pp. 98–99

- Paulson 2000 pp. 92–93

- Dudden 1966 pp. 97, 99

- Dudden 1966 pp. 96–97

- Paulson 2000 p. 71

- Dudden 1966 p. 99

- Roberts 1963 39–52

- Hume 1988 pp. 118–120

References

- Battestin, Martin, and Battestin, Ruthe. Henry Fielding: a Life. London: Routledge, 1993.

- Dudden, F. Homes. Henry Fielding: His Life, Works and Times. Hamden, Conn.: Archon Books, 1966.

- Hume, Robert. Fielding and the London Theater. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988.

- Pagliaro, Harold. Henry Fielding: A Literary Life. New York: St Martin's Press, 1998.

- Paulson, Ronald. The Life of Henry Fielding: A Critical Biography. Malden: Blackwell Publishing, 2000.

- Roberts, Edgar. "Mr. Seedo's London Career and His Work with Henry Fielding" Philological Quarterly, 45 (1966): 179–190.