Tod Browning

Tod Browning (born Charles Albert Browning Jr.; July 12, 1880 – October 6, 1962) was an American film director, film actor, screenwriter and vaudeville performer.[1] Browning's career spanned the silent film and sound film eras. Best known as the director of Dracula (1931),[2] Freaks (1932),[3] and silent film collaborations with Lon Chaney and Priscilla Dean, Browning directed many movies in a wide range of genres, between 1915 and 1939.

Tod Browning | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Charles Albert Browning Jr. July 12, 1880 Louisville, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Died | October 6, 1962 (aged 82) Malibu, California, U.S. |

| Occupation |

|

| Years active | 1913–1939 |

Early life

_-_12.jpg)

Browning was born as Charles Albert Browning, Jr., in Louisville, Kentucky, the second son of Charles Albert and Lydia Browning, and the nephew of baseball star Pete Browning. As a young boy, he put on amateur plays in his backyard. He was fascinated by the circus and carnival life, and at the age of 16 he ran away from his well-to-do family to become a performer.

Changing his name to "Tod", he traveled extensively with sideshows, carnivals, and circuses. His jobs included working as a talker for the Wild Man of Borneo, performing a live burial act in which he was billed as "The Living Corpse", and performing as a clown with the Ringling Brothers Circus. He drew on this experience as inspiration for some of his film work.

He performed in vaudeville as an actor, magician's assistant, blackface comedian (in an act called The Lizard and the Coon with comedian Roy C. jones) and dancer. He appeared in the Mutt and Jeff sketch in the 1912 burlesque revue The Wheel of Mirth with comedian Charles Murray.

Beginnings of a film career

Later, while Browning was working as director of a variety theater in New York City, he met D.W. Griffith, who was also from Louisville. He began acting with Murray on single-reel nickelodeon comedies for Griffith and the Biograph Company.

In 1913 Griffith split from Biograph and moved to California. Browning followed and continued to act in Griffith's films, now for Reliance-Majestic Studios, including a stint as an extra in the epic Intolerance. Around that time he began directing, eventually directing 11 short films for Reliance-Majestic. Between 1913 and 1919, Browning appeared as an actor in approximately 50 motion pictures.

On June 16, 1915, Browning's career almost ended when he crashed his car at full speed into another vehicle described as a "street work car loaded with iron rails".[4] He reportedly did not see the work vehicle's "rear lamp".[4] Two fellow film actors, Elmer Booth and George Siegmann, were passengers in his car. Booth was killed instantly, and Siegmann suffered broken ribs, a deeply lacerated thigh, and internal injuries; but he recovered.[5]. Browning was badly injured as well, including a shattered right leg and the loss of his front teeth. During his lengthy convalescence, he wrote scripts, and did not return to active film work until 1917. Elmer Booth's sister, Margaret, who later became a prominent editor for MGM, never forgave Browning for the loss of her brother.[5]

Silent feature films

Browning's feature film debut was Jim Bludso (1917), about a riverboat captain who sacrifices himself to save his passengers from a fire. It was well received.

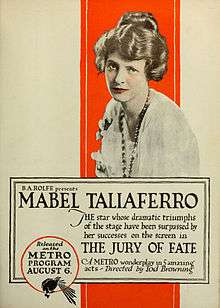

Browning moved back to New York in 1917. He directed two films for Metro Studios, Peggy, the Will O' the Wisp and The Jury of Fate. Both starred Mabel Taliaferro, the latter in a dual role achieved with double exposure techniques that were groundbreaking for the time. He moved back to California in 1918 and produced two more films for Metro, The Eyes of Mystery and Revenge.

In the spring of 1918, he left Metro and joined Bluebird Productions, a subsidiary of Universal Pictures, where he met Irving Thalberg. Thalberg paired Browning with Lon Chaney for the first time for the film The Wicked Darling (1919), a melodrama in which Chaney played a thief who forces a poor girl (Priscilla Dean) from the slums into a life of crime and possibly prostitution. Browning and Chaney ultimately made 10 films together over the next decade.

The death of his father sent Browning into a depression that led to alcoholism. He was laid off by Universal and his wife left him. However, he recovered, reconciled with his wife, and got a one-picture contract with Goldwyn Pictures. The film he produced for Goldwyn, The Day of Faith, was a moderate success, putting his career back on track.

Thalberg reunited Browning with Lon Chaney for The Unholy Three (1925), the story of three circus performers who concoct a scheme to use disguises to con and steal jewels from rich people. Browning's circus experience shows in his sympathetic portrayal of the antiheroes. The film was a resounding success, so much so that it was later remade in 1930 as Lon Chaney's first (and only) talkie shortly before his death later that same year. Browning and Chaney embarked on a series of popular collaborations, including The Blackbird and The Road to Mandalay.

The Unknown (1927), featuring Chaney as an armless knife thrower and Joan Crawford as his scantily clad carnival girl obsession, originally was titled Alonzo the Armless and could be considered a precursor to Freaks in that it concerns a love triangle involving a circus freak, a beauty, and a strongman.

London After Midnight (1927) was Browning's first foray into the vampire genre and is a highly sought-after lost film which starred Chaney, Conrad Nagel, and Marceline Day. The last known print of London After Midnight was destroyed in an MGM studio fire in 1965. In 2002, a photographic reconstruction of London After Midnight was produced by Rick Schmidlin for Turner Classic Movies.

Browning and Chaney's final collaboration was Where East Is East (1929), of which only incomplete prints have survived. Browning's first talkie was The Thirteenth Chair (1929), which was also released as a silent and featured Bela Lugosi, who had a leading part as the uncanny inspector, Delzante, solving the mystery with the aid of the spirit medium. This film was directed shortly after Browning's vacation trip to Germany (arriving in the Port of New York, November 12, 1929).

Sound films

After Chaney's death in 1930, Browning was hired by his old employer Universal Pictures to direct Dracula (1931).[2] Although Browning wanted to hire an unknown European actor for the title role and have him be mostly offscreen as a sinister presence, budget constraints and studio interference necessitated the casting of Bela Lugosi and a more straightforward approach.

After directing the boxing melodrama Iron Man (1931), Browning began work on Freaks (1932).[3] Based on the short story "Spurs" by Clarence Aaron "Tod" Robbins, the screenwriter of The Unholy Three, the film concerns a love triangle among a wealthy dwarf, a gold-digging aerialist, and a strongman; a murder plot; and the vengeance dealt out by the dwarf and his fellow circus freaks. The film was highly controversial, even after heavy editing to remove many disturbing scenes, and was a commercial failure and banned in the United Kingdom for 30 years.[6]

His career derailed, Browning found himself unable to get his requested projects greenlighted. After directing the drama Fast Workers (1933) starring John Gilbert, who was also not in good standing with the studio, he was allowed to direct a remake of London After Midnight, originally titled Vampires of Prague but later retitled Mark of the Vampire (1935). In the remake, the roles played by Lon Chaney in the original were split between Lionel Barrymore and Béla Lugosi (spoofing his Dracula image).

After that, Browning directed The Devil-Doll (1936), originally titled The Witch of Timbuctoo, from his own story.[7] The picture starred Lionel Barrymore as an escapee from an island prison who avenges himself on the people who imprisoned him using living "dolls" who are actually people shrunk to doll-size and magically placed under Barrymore's hypnotic control. Browning's final film was the murder mystery Miracles for Sale (1939).

Filmography

Director

- The Lucky Transfer (1915)

- The Slave Girl (1915)

- An Image of the Past (1915)

- The Highbinders (1915)

- The Story of a Story (1915)

- The Spell of the Poppy (1915)

- The Electric Alarm (1915)

- The Living Death (1915)

- The Burned Hand (1915)

- The Woman from Warren's (1915)

- Little Marie (1915)

- The Fatal Glass of Beer (1916)

- Everybody's Doing It (1916)

- Puppets (1916)

- Jim Bludso (1917)

- A Love Sublime (1917)

- Hands Up! (1917)

- Peggy, the Will O' the Wisp (1917)

- The Jury of Fate (1917)

- The Legion of Death (1918)

- The Eyes of Mystery (1918)

- Revenge (1918)

- Which Woman? (1918)

- The Deciding Kiss (1918)

- The Brazen Beauty (1918)

- Set Free (1918)

- The Wicked Darling (1919)

- The Exquisite Thief (1919)

- The Unpainted Woman (1919)

- The Petal on the Current (1919)

- Bonnie Bonnie Lassie (1919)

- The Virgin of Stamboul (1920)

- Outside the Law (1920)

- No Woman Knows (1921)

- The Wise Kid (1922)

- Man Under Cover (1922)

- Under Two Flags (1922)

- Drifting (1923)

- The Day of Faith (1923)

- White Tiger (1923)

- The Dangerous Flirt (1924)

- Silk Stocking Sal (1924)

- The Unholy Three (1925)

- The Mystic (1925)

- Dollar Down (1925)

- The Blackbird (1926)

- The Road to Mandalay (1926)

- The Show (1927)

- The Unknown (1927)

- London After Midnight (1927)

- The Big City (1928)

- West of Zanzibar (1928)

- Where East Is East (1929)

- The Thirteenth Chair (1929)

- Outside the Law (1930)

- Dracula (1931)

- Iron Man (1931)

- Freaks (1932)

- Fast Workers (1933)

- Mark of the Vampire (1935)

- The Devil-Doll (1936)

- Miracles for Sale (1939)

Actor

- Intolerance (1916) - Crook (uncredited)

- Dracula (1931) - Harbormaster (voice, uncredited, final film role)

Further reading

- Dark Carnival (1995) (ISBN 0-385-47406-7) by David J. Skal and Elias Savada.

- The Films of Tod Browning (2006) (ISBN 978-1-904772-51-4) edited by Bernd Herzogenrath.

References

- "Tod Browning". The New York Times.

- Hall, Mordaunt (1931). "Dracula". The New York Times.

- "Freaks". The New York Times. 1932.

- "Elmer Booth Killed", Moving Picture World, July 3, 1915, p.75. Internet Archive, San Francisco, California. Retrieved November 18, 2019.

- Ska, David J. (2001). The Monster Show: A Cultural History of Horror. Macmillan. p. 35. ISBN 978-0571199969.

- King, Susan (2011). "'Dracula,' 'Mark of the Vampire' bring vintage bite to Aero Theatre". Los Angeles Times, May 18, 2011.

- Skal, David J.; Elias Savada. Dark Carnival. New York: Anchor, 1995, pp. 307-308 ISBN 0-385-47406-7

External links

- Works by or about Tod Browning at Internet Archive

- Tod Browning on IMDb

- Tod Browning bibliography via UC Berkeley Media Resources Center

- Tod Browning at AllMovie

- Tod Browning at Find a Grave

- Tod Browning at Virtual History