Euphorbia

Euphorbia is a very large and diverse genus of flowering plants, commonly called spurge, in the spurge family (Euphorbiaceae). "Euphorbia" is sometimes used in ordinary English to collectively refer to all members of Euphorbiaceae (in deference to the type genus), not just to members of the genus.[2] Some euphorbias are commercially widely available, such as poinsettias at Christmas. Some are commonly cultivated as ornamentals, or collected and highly valued for the aesthetic appearance of their unique floral structures, such as the crown of thorns plant (Euphorbia milii). Euphorbias from the deserts of Southern Africa and Madagascar have evolved physical characteristics and forms similar to cacti of North and South America, so they (along with various other kinds of plants) are often incorrectly referred to as cacti.[3] Some are used as ornamentals in landscaping, because of beautiful or striking overall forms, and drought and heat tolerance.[4][5]

| Euphorbia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Euphorbia cf. serrata | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Malpighiales |

| Family: | Euphorbiaceae |

| Subfamily: | Euphorbioideae |

| Tribe: | Euphorbieae |

| Subtribe: | Euphorbiinae Griseb. |

| Genus: | Euphorbia L. |

| Type species | |

| Euphorbia antiquorum | |

| Subgenera | |

|

Chamaesyce | |

| Diversity | |

| c. 2008 species | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

|

List

| |

Euphorbias range from tiny annual plants to large and long-lived trees.[5] The genus has over[4] or about 2,000 members,[6] making it one of the largest genera of flowering plants.[7][8] It also has one of the largest ranges of chromosome counts, along with Rumex and Senecio.[7] Euphorbia antiquorum is the type species for the genus Euphorbia.[9] It was first described by Carl Linnaeus in 1753 in Species Plantarum.

The plants share the feature of having a poisonous, milky, white, latex-like sap, and unusual and unique floral structures.[4] The genus may be described by properties of its members' gene sequences, or by the shape and form (morphology) of its heads of flowers. When viewed as a whole, the head of flowers looks like a single flower (a pseudanthium).[4] It has a unique kind of pseudanthium, called a cyathium, where each flower in the head is reduced to its barest essential part needed for sexual reproduction.[4] The individual flowers are either male or female, with the male flowers reduced to only the stamen, and the females to the pistil.[4] These flowers have no sepals, petals, or other parts that are typical of flowers in other kinds of plants.[4] Structures supporting the flower head and other structures underneath have evolved to attract pollinators with nectar, and with shapes and colors that function in a way petals and other flower parts do in other flowers. It is the only genus of plants that has all three kinds of photosynthesis, CAM, C3 and C4.[4]

Misidentification as cacti

Among laypeople, Euphorbia species are among the plant taxa most commonly confused with cacti, especially the stem succulents.[10] Euphorbias secrete a sticky, milky-white fluid with latex, but cacti do not.[10] Individual flowers of euphorbias are usually tiny and nondescript (although structures around the individual flowers may not be), without petals and sepals, unlike cacti, which often have fantastically showy flowers.[10] Euphorbias from desert habitats with growth forms similar to cacti have thorns, which are different from the spines of cacti.[10]

Etymology

The common name "spurge" derives from the Middle English/Old French espurge ("to purge"), due to the use of the plant's sap as a purgative. The botanical name Euphorbia derives from Euphorbos, the Greek physician of King Juba II of Numidia (52–50 BC – 23 AD), who married the daughter of Anthony and Cleopatra.[11] Juba was a prolific writer on various subjects, including natural history. Euphorbos wrote that one of the cactus-like euphorbias (now called Euphorbia obtusifolia ssp. regis-jubae) was used as a powerful laxative.[11] In 12 BC, Juba named this plant after his physician Euphorbos, as Augustus Caesar had dedicated a statue to the brother of Euphorbos, Antonius Musa, who was the personal physician of Augustus.[11] In 1753, botanist and taxonomist Carl Linnaeus assigned the name Euphorbia to the entire genus in the physician's honor.[12]

Description

The plants are annual, biennial or perennial herbs, woody shrubs, or trees with a caustic, poisonous milky latex. The roots are fine or thick and fleshy or tuberous. Many species are more or less succulent, thorny, or unarmed. The main stem and mostly also the side arms of the succulent species are thick and fleshy, 15–91 cm (6–36 in) tall. The deciduous leaves may be opposite, alternate, or in whorls. In succulent species, the leaves are mostly small and short-lived. The stipules are mostly small, partly transformed into spines or glands, or missing.

Inflorescence and fruit

Like all members of the family Euphorbiaceae, spurges have unisexual flowers.

In Euphorbia, flowers occur in a head, called the cyathium (plural cyathia). Each male or female flower in the cyathium head has only its essential sexual part, in males the stamen, and in females the pistil. The flowers do not have sepals, petals, or nectar to attract pollinators, although other nonflower parts of the plant have an appearance and nectar glands with similar roles. Euphorbias are the only plants known to have this kind of flower head.[13]

Nectar glands and nectar that attract pollinators are held in the involucre, a cup-like part below and supporting the cyathium head. The "involucre" in the genus Euphorbia is not to be confused with the "involucre" in family Asteraceae members, which is a collection of bracts called phyllaries, which surround and encase the unopened flower head, then support the receptacle under it after the flower head opens.

The involucre is above and supported by bract-like modified leaf structures (usually in pairs) called cyathophylls', or cyathial leaves. The cyathophyll often has a superficial appearance of being petals of a flower.

Euphorbia flowers are tiny, and the variation attracting different pollinators, with different forms and colors occurs, in the cyathium, involucre, cyathophyll, or additional parts such as glands that attached to these.

The collection of many flowers may be shaped and arranged to appear collectively as a single individual flower, sometimes called a pseudanthium in the Asteraceae, and also in Euphorbia.

The majority of species are monoecious (bearing male and female flowers on the same plant), although some are dioecious with male and female flowers occurring on different plants. It is not unusual for the central cyathia of a cyme to be purely male, and for lateral cyathia to carry both sexes. Sometimes, young plants or those growing under unfavorable conditions are male only, and only produce female flowers in the cyathia with maturity or as growing conditions improve.

The female flowers reduced to a single pistil usually split into three parts, often with two stigmas at each tip. Male flowers often have anthers in twos. Nectar glands usually occur in fives,[14] may be as few as one,[14] and may be fused into a "U" shape.[13] The cyathophylls often occur in twos, are leaf-like, and may be showy and brightly coloured and attractive to pollinators, or be reduced to barely visible tiny scales.

The fruits are three- or rarely two-compartment capsules, sometimes fleshy, but almost always ripening to a woody container that then splits open, sometimes explosively. The seeds are four-angled, oval, or spherical, and some species have a caruncle.

Xerophytes and succulents

In the genus Euphorbia, succulence in the species has often evolved divergently and to differing degrees. Sometimes, it is difficult to decide, and is a question of interpretation, whether or not a species is really succulent or "only" xerophytic. In some cases, especially with geophytes, plants closely related to the succulents are normal herbs. About 850 species are succulent in the strictest sense. If one includes slightly succulent and xerophytic species, this figure rises to about 1000, representing about 45% of all Euphorbia species.

Irritants

The milky sap of spurges (called "latex") evolved as a deterrent to herbivores. It is white, and transparent when dry, except in E. abdelkuri, where it is yellow. The pressurized sap seeps from the slightest wound and congeals after a few minutes in air. The skin-irritating and caustic effects are largely caused by varying amounts of diterpenes. Triterpenes such as betulin and corresponding esters are other major components of the latex.[15] In contact with mucous membranes (eyes, nose, mouth), the latex can produce extremely painful inflammation. The sap has also been known to cause mild to extreme Keratouveitis, which affects vision.[16] Therefore, spurges should be handled with caution and kept away from children and pets. Wearing eye protection while working in close contact with Euphorbia is advised.[17] Latex on skin should be washed off immediately and thoroughly. Congealed latex is insoluble in water, but can be removed with an emulsifier such as milk or soap. A physician should be consulted if inflammation occurs, as severe eye damage including permanent blindness may result from exposure to the sap.[18] When large succulent spurges in a greenhouse are cut, vapours can cause irritation to the eyes and throat several metres away. Precautions, including sufficient ventilation, are required.

Uses

Several spurges are grown as garden plants, among them poinsettia (E. pulcherrima) and the succulent E. trigona. E. pekinensis (Chinese: 大戟; pinyin: dàjǐ) is used in traditional Chinese medicine, where it is regarded as one of the 50 fundamental herbs. Several Euphorbia species are used as food plants by the larvae of some Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths), like the spurge hawkmoths (Hyles euphorbiae and Hyles tithymali), as well as the giant leopard moth.

Ingenol mebutate, a drug used to treat actinic keratosis, is a diterpenoid found in Euphorbia peplus.

Euphorbias are often used as hedging plants in many parts of Africa.[19]

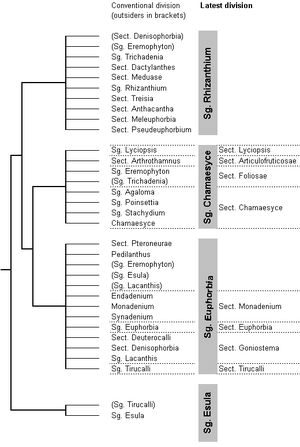

Systematics and taxonomy

The present taxon "Euphorbia" corresponds to its own former subtribe, the Euphorbiinae. It has over 2000 species.[4] Morphological description using the presence of a cyathium (see section above) is consistent with nuclear and chloroplast DNA sequence data in testing of about 10% of its members. This testing supports inclusion of formerly other genera as being best placed in this single genus, including Chamaesyce, Monadenium, Pedilanthus, and poinsettia (E. pulcherrima).

Genetic tests have shown that similar flower head structures or forms within the genus, might not mean close ancestry within the genus. The genetic data show that within the genus, convergent evolution of inflorescence structures may be from ancestral subunits that are not related. So using morphology within the genus becomes problematic for further subgeneric grouping. As stated on the Euphorbia Planetary Biodiversity Inventory project webpage:[4]

Previous morphologically based delimitations of subgenera or sections within the genus should not be taken at face value. The genus is in fact rife with striking examples of morphological convergence in cyathial and vegetative features, which justifies a global approach to studying the genus to obtain a proper phylogenetic understanding of the whole group.... The bottom line is that a number of clades have been placed inside or outside of Euphorbia at different times... few of the subgeneric circumscriptions hold up under DNA sequence analysis.

According to a 2002 publication on studies of DNA sequence data,[20][21][22] most of the smaller "satellite genera" around the huge genus Euphorbia nest deep within the latter. Consequently, these taxa, namely the never generally accepted genus Chamaesyce, as well as the smaller genera Cubanthus,[23] Elaeophorbia, Endadenium, Monadenium, Synadenium, and Pedilanthus were transferred to Euphorbia. The entire subtribe Euphorbiinae now consists solely of the genus Euphorbia.

Selected species

See List of Euphorbia species for complete list.

- Euphorbia albomarginata – rattlesnake weed, white-margined sandmat

- Euphorbia amygdaloides – wood spurge

- Euphorbia antisyphilitica – candelilla

- Euphorbia backeri

- Euphorbia balsamifera – sweet tabaiba (Canary Islands)[24]

- Euphorbia bulbispina

- Euphorbia canariensis – Canary Island spurge, Hercules club (Canary Islands)[25]

- Euphorbia caput-medusae – Medusa's head (South Africa)

- Euphorbia ceratocarpa – (Sicily and southern Italy)

- Euphorbia characias – Mediterranean spurge

- Euphorbia coerulescens - Haw[26]

- Euphorbia cotinifolia – copper tree

- Euphorbia cyathophora – fire-on-the-mountain

- Euphorbia cyparissias – Cypress spurge

- Euphorbia decidua

- Euphorbia dendroides – tree spurge

- Euphorbia epithymoides – cushion spurge

- Euphorbia esula – leafy spurge

- Euphorbia franckiana

- Euphorbia fulgens – scarlet plume

- Euphorbia grandicornis – Euphorbia with large horn

- Euphorbia grantii – African milk bush

- Euphorbia gregersenii – Gregersen's spurge

- Euphorbia griffithii – Griffith's spurge

- Euphorbia helioscopia – sun spurge

- Euphorbia heterophylla – painted euphorbia, desert poinsettia, fireplant, paint leaf, kaliko

- Euphorbia hirta – asthma-plant

- Euphorbia hispida

- Euphorbia horrida – African milk barrel

- Euphorbia ingens – candelabra tree

- Euphorbia japonica - E.bupleurifolia x E.suzannae

- Euphorbia labatii

- Euphorbia lactea – mottled spurge, frilled fan, elkhorn

- Euphorbia lathyris – caper spurge, paper spurge, gopher spurge, gopher plant, mole plant

- Euphorbia leuconeura – Madagascar jewel

- Euphorbia maculata – spotted spurge, prostrate spurge

- Euphorbia marginata – snow on the mountain

- Euphorbia mammillaris

- Euphorbia maritae

- Euphorbia milii – crown-of-thorns, Christ plant

- Euphorbia misera – cliff spurge, Baja California, Southern California

- Euphorbia myrsinites – myrtle spurge, creeping spurge, donkey tail

- Euphorbia obesa

- Euphorbia paralias – sea spurge

- Euphorbia pekinensis – Peking spurge

- Euphorbia peplis – purple spurge

- Euphorbia peplus – petty spurge

- Euphorbia polychroma – bonfire

- Euphorbia psammogeton – sand spurge

- Euphorbia pulcherrima – poinsettia, Mexican flame leaf, Christmas star, winter rose, noche buena, lalupatae, pascua, Atatürk çiçeği (Turkish)

- Euphorbia purpurea – Darlington's glade spurge, glade spurge, or purple spurge

- Euphorbia resinifera – resin spurge

- Euphorbia rigida – gopher spurge, upright myrtle spurge

- Euphorbia serrata – serrated spurge, sawtooth spurge

- Euphorbia sotetsu kirin – (E.bupleurifolia x E.mammillaris) x E.bupleurifolia

- Euphorbia tirucalli – Indian tree spurge, milk bush, pencil tree, firestick

- Euphorbia tithymaloides – devil's backbone, redbird cactus, cimora misha (Peru)

- Euphorbia trigona – African milk tree, cathedral cactus, Abyssinian euphorbia

- Euphorbia tuberosa

- Euphorbia virosa – gifboom or poison tree

Hybrids

Euphorbia has been extensively hybridised for garden use, with many cultivars available commercially. Moreover, some hybrid plants have been found growing in the wild, for instance E. × martini Rouy,[27] a cross of E. amygdaloides × E. characias subsp. characias, found in southern France.

Subgenera

The genus Euphorbia is one of the largest and most complex genera of flowering plants, and several botanists have made unsuccessful attempts to subdivide the genus into numerous smaller genera. According to the recent phylogenetic studies,[20][21][22] Euphorbia can be divided into four subgenera, each containing several sections and groups. Of these, subgenus Esula is the most basal. The subgenera Chamaesyce and Euphorbia are probably sister taxa, but very closely related to subgenus Rhizanthium. Extensive xeromorph adaptations in all probability evolved several times; it is not known if the common ancestor of the cactus-like Rhizanthium and Euphorbia lineages had been xeromorphic—in which case a more normal morphology would have re-evolved namely in Chamaesyce—or whether extensive xeromorphism is entirely polyphyletic even to the level of the subgenera.

- Esula

Wood spurge

Wood spurge

Euphorbia amygdaloides Cypress spurge

Cypress spurge

Euphorbia cyparissias Leafy spurge

Leafy spurge

Euphorbia esula- Myrtle spurge

Euphorbia myrsinites

- Rhizanthium

Euphorbia meloformis ssp. valida

Euphorbia meloformis ssp. valida

- Chamaesyce

- Painted euphorbia

Euphorbia heterophylla  Poinsettia

Poinsettia

Euphorbia pulcherrima Euphorbia rivae

Euphorbia rivae

- Euphorbia

Euphorbia attastoma var. attastoma

Euphorbia attastoma var. attastoma Euphorbia confinalis ssp. rhodesica

Euphorbia confinalis ssp. rhodesica Euphorbia lupulina

Euphorbia lupulina Euphorbia neriifolia

Euphorbia neriifolia

References

- "Euphorbia L." Plants of the World Online. Board of Trustees of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- "Definition of Euphorbia". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Merriam-Webster, Inc. Retrieved 1 Feb 2019.

- "Cacti or Not? Many succulents look like cacti, but are not". CactiGuide.com. Retrieved 1 Feb 2019.

- "Euphorbia PBI - Project Description". Planetary Biodiversity Inventory (PBI). Retrieved 1 Feb 2019.

- "Euphorbia". Fine Gardening. The Taunton Press, Inc.

- "World Checklist of Selected Plant Families (WCSP)". Kew Science. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 16 Apr 2011.

- Stebbins GL, Hoogland RD (1976). "Species diversity, ecology and evolution in a primitive Angiosperm genus:Hibbertia (Dilleniaceae)". Plant Syst. Evol. 125 (3): 139–154. doi:10.1007/BF00986147.

- "Euphorbia botany lesson". Houzz. 30 Jun 2010. Retrieved 1 Feb 2019.

- Carter S (2002). "Euphorbia". In Eggli U (ed.). Dicotyledons. Illustrated Handbook of Succulent Plants. 5. Springer. p. 102. ISBN 978-3-540-41966-2.

- Beaulieu, D (21 Oct 2018). "Do You Know the Difference Between Cacti and Succulents?". The Spruce. Dotdash. Retrieved 1 Feb 2019.

- Dale N (1986). Flowering Plants of the Santa Monica Mountains. California Native Plant Society. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-88496-239-7.

- Linnaeus C (1753). "Euphorbia". Species Plantarum (1st ed.). p. 450.

- "About the genus Euphorbia". Planetary Biodiversity Inventory (PBI). Retrieved 1 Feb 2019.

- Stein, G. (22 Apr 2011). "Euphorbia "Flowers," an introduction to the amazing Cyathia". Dave's Garden. Retrieved 1 Feb 2019.

- Hodgkiss, RJ. "Research into euphorbia latex and irritant ingredients". www.euphorbia.de. Retrieved 2 Nov 2013.

- Basak, Samar K; Bakshi, Partho K; Basu, Sabitabrata; Basak, Soham (2009). "Keratouveitis caused by Euphorbia plant sap". Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. 57 (4): 311–313. doi:10.4103/0301-4738.53060. ISSN 0301-4738. PMC 2712704. PMID 19574703.

- Basak, Samar K; Bakshi, Partho K; Basu, Sabitabrata; Basak, Soham (2009). "Keratouveitis caused by Euphorbia plant sap". Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. 57 (4): 311–313. doi:10.4103/0301-4738.53060. ISSN 0301-4738. PMC 2712704. PMID 19574703.

- Eke T, Al-Husainy S, Raynor MK (2000). "The spectrum of ocular inflammation caused by Euphorbia plant sap". Arch. Ophthalmol. 118 (1): 13–16. doi:10.1001/archopht.118.1.13. PMID 10636407.

- Adamson J (2011). Born Free: The Full Story. Pan Macmillan. p. 23. ISBN 9780330536745. Retrieved 6 Oct 2014.

- Steinmann VW, Porter JM (2002). "Phylogenetic relationships in Euphorbieae (Euphorbiaceae) based on ITS and ndhF sequence data". Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 89 (4): 453–490. doi:10.2307/3298591. JSTOR 3298591.

- Steinmann VW (2003). "The submersion of Pedilanthus into Euphorbia (Euphorbiaceae)". Acta Botanica Mexicana (65): 45–50. doi:10.21829/abm65.2003.961. ISSN 2448-7589.

- Bruyns PV, Mapaya RJ, Hedderson TJ (2006). "A new subgeneric classification for Euphorbia (Euphorbiaceae) in southern Africa based on ITS and psbA-trnH sequence data". Taxon. 55 (2): 397–420. doi:10.2307/25065587. JSTOR 25065587.

- Steinmann VW, van Ee B, Berry PE, Gutiérrez J (2007). "The systematic position of Cubanthus and other shrubby endemic species of Euphorbia (Euphorbiaceae) in Cuba". Anales Jard. Bot. Madrid. 64 (2): 123–133. doi:10.3989/ajbm.2007.v64.i2.167.

- "Euphorbia balsamifera". Flora de Canarias. Retrieved 1 Feb 2019.

- "Euphorbia canariensis". Flora de Canarias. Retrieved 1 Feb 2019.

- Euphorbia coerulescens

- "World Checklist of Selected Plant Families (WCSP) - Euphorbia × martini Rouy, Ill. Pl. Eur. 13: 107 (1900)". Kew Science. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 26 Feb 2018.

Further reading

- Buddensiek V (2005). Succulent Euphorbia plus (CD-ROM). Volker Buddensiek Verlag.

- Carter S (1982). New Succulent Spiny Euphorbias from East Africa. Hooker's Icones plantarum. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. ISBN 9781878762726.

- Carter S, Eggli U (1997). The CITES Checklist of Succulent Euphorbia Taxa (Euphorbiaceae). Germany: German Federal Agency for Nature Conservation. ISBN 9783896246097.

- Carter S, Smith AL (1988). "Euphorbiaceae". Flora of Tropical East Africa. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

- Noltee F (2001). Succulents in the wild and in cultivation, Part 2 Euphorbia to Juttadinteria (CD-ROM).

- Urs E, ed. (2002). Sukkulenten-Lexikon (in German). Vol. 2: Zweikeimblättrige Pflanzen (Dicotyledonen). Eugen Ulmer Verlag. ISBN 9783800139156.

- Gómez-Valcárcel M, Fuentes-Páez G (2016). "Euphorbia grandicornis Sap Keratouveitis: A Case Report". Case Rep. Ophthalmol. 7 (1): 125–129. doi:10.1159/000444438. PMC 4899636. PMID 27293414.

- Everitt J, Lonard R, Little C (2007). Weeds in South Texas and Northern Mexico. Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press. ISBN 9780896726147.

- Pritchard A (2003). Introduction to the Euphorbiaceae (in Italian). Cactus & Co. ISBN 9788890051142.

- Schwartz H, ed. (1983). The Euphorbia Journal. Mill Valley, CA: Strawberry Press.

- Singh M (1994). Succulent Euphorbiaceae of India. India: Meena Singh (self published). ASIN B004PFR2G6.

- Turner R (1995). Euphorbias: A Gardeners' Guide. Bastford: Timber Press, Inc. ISBN 9780881923308.

- Soumen A (2010). "A revision of geophytic euphorbia species from India" (PDF). Euphorbia World. 6 (1): 18–21. ISSN 1746-5397.

- Pritchard A (2010). Monadenium. Venegono Superiore: Cactus & Co. ISBN 9788895018027.