Tinbergen's four questions

Tinbergen's four questions, named after Nikolaas Tinbergen, are complementary categories of explanations for animal behaviour. These are also commonly referred to as levels of analysis.[1] It suggests that an integrative understanding of behaviour must include: ultimate (evolutionary) explanations, in particular the behaviour (1) adaptive function and (2) phylogenetic history; and the proximate explanations, in particular the behaviour (3) underlying mechanisms and (4) ontogenetic/developmental history.[2]

Four categories of questions and explanations

When asked about the purpose of sight in humans and animals, even elementary-school children can answer that animals have vision to help them find food and avoid danger (function/adaptation). Biologists have three additional explanations: sight is caused by a particular series of evolutionary steps (phylogeny), the mechanics of the eye (mechanism/causation), and even the process of an individual's development (ontogeny).

This schema constitutes a basic framework of the overlapping behavioural fields of ethology, behavioural ecology, comparative psychology, sociobiology, evolutionary psychology, and anthropology. It was in fact Julian Huxley who identified the first three questions, Niko Tinbergen gave only the fourth question, but Julian Huxley's questions failed to distinguish between survival value and evolutionary history, so Tinbergen's fourth question helped resolve this problem.[3]

Table of categories

| Diachronic versus synchronic perspective | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic view Explanation of current form in terms of a historical sequence |

Static view Explanation of the current form of species | ||

| How vs. why questions | Proximate view How an individual organism's structures function |

Ontogeny (development) Developmental explanations for changes in individuals, from DNA to their current form |

Mechanism (causation) Mechanistic explanations for how an organism's structures work |

| Ultimate (evolutionary) view Why a species evolved the structures (adaptations) it has |

Phylogeny (evolution) The history of the evolution of sequential changes in a species over many generations |

Function (adaptation) A species trait that solves a reproductive or survival problem in the current environment | |

Evolutionary (ultimate) explanations

1 Function (adaptation)

Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection is the only scientific explanation for why an animal's behaviour is usually well adapted for survival and reproduction in its environment. However, claiming that a particular mechanism is well suited to the present environment is different from claiming that this mechanism was selected for in the past due to its history of being adaptive.[4] The literature conceptualizes the relationship between function and evolution in two ways. On the one hand, function and evolution are often presented as separate and distinct explanations of behaviour.[5]

On the other hand, the common definition of adaptation, a central concept in evolution, is a trait that was functional to the reproductive success of the organism and that is thus now present due to being selected for; that is, function and evolution are inseparable. However a trait can have a current function that is adaptive without being an adaptation in this sense, if for instance the environment has changed. Imagine an environment in which having a small body suddenly conferred benefit on an organism when previously body size had had no effect on survival.[6]

A small body's function in the environment would then be adaptive, but it wouldn't become an adaptation until enough generations had passed in which small bodies were advantageous to reproduction for small bodies to be selected for. Given this, it is best to understand that presently functional traits might not all have been produced by natural selection.[7] The term "function" is preferable to "adaptation", because adaptation is often construed as implying that it was selected for due to past function.

It corresponds to Aristotle's final cause.[8]

2 Phylogeny (evolution)

Evolution captures both the history of an organism via its phylogeny, and the history of natural selection working on function to produce adaptations.[9] There are several reasons why natural selection may fail to achieve optimal design (Mayr 2001:140–143; Buss et al. 1998). One entails random processes such as mutation and environmental events acting on small populations. Another entails the constraints resulting from early evolutionary development. Each organism harbors traits, both anatomical and behavioural, of previous phylogenetic stages, since many traits are retained as species evolve.

Reconstructing the phylogeny of a species often makes it possible to understand the "uniqueness" of recent characteristics: Earlier phylogenetic stages and (pre-) conditions which persist often also determine the form of more modern characteristics. For instance, the vertebrate eye (including the human eye) has a blind spot, whereas octopus eyes do not. In those two lineages, the eye was originally constructed one way or the other. Once the vertebrate eye was constructed, there were no intermediate forms that were both adaptive and would have enabled it to evolve without a blind spot.

It corresponds to Aristotle's formal cause.[8]

Proximate explanations

3 Mechanism (causation)

Some prominent classes of Proximate causal mechanisms include:

- The brain: For example, Broca's area, a small section of the human brain, has a critical role in linguistic capability.

- Hormones: Chemicals used to communicate among cells of an individual organism. Testosterone, for instance, stimulates aggressive behaviour in a number of species.

- Pheromones: Chemicals used to communicate among members of the same species. Some species (e.g., dogs and some moths) use pheromones to attract mates.

In examining living organisms, biologists are confronted with diverse levels of complexity (e.g. chemical, physiological, psychological, social). They therefore investigate causal and functional relations within and between these levels. A biochemist might examine, for instance, the influence of social and ecological conditions on the release of certain neurotransmitters and hormones, and the effects of such releases on behaviour, e.g. stress during birth has a tocolytic (contraction-suppressing) effect.

However, awareness of neurotransmitters and the structure of neurons is not by itself enough to understand higher levels of neuroanatomic structure or behaviour: "The whole is more than the sum of its parts." All levels must be considered as being equally important: cf. transdisciplinarity, Nicolai Hartmann's "Laws about the Levels of Complexity."

It corresponds to Aristotle's efficient cause.[8]

4 Ontogeny (development)

In the latter half of the twentieth century, social scientists debated whether human behaviour was the product of nature (genes) or nurture (environment in the developmental period, including culture).

An example of interaction (as distinct from the sum of the components) involves familiarity from childhood. In a number of species, individuals prefer to associate with familiar individuals but prefer to mate with unfamiliar ones (Alcock 2001:85–89, Incest taboo, Incest). By inference, genes affecting living together interact with the environment differently from genes affecting mating behaviour. A homely example of interaction involves plants: Some plants grow toward the light (phototropism) and some away from gravity (gravitropism).

Many forms of developmental learning have a critical period, for instance, for imprinting among geese and language acquisition among humans. In such cases, genes determine the timing of the environmental impact.

A related concept is labeled "biased learning" (Alcock 2001:101–103) and "prepared learning" (Wilson, 1998:86–87). For instance, after eating food that subsequently made them sick, rats are predisposed to associate that food with smell, not sound (Alcock 2001:101–103). Many primate species learn to fear snakes with little experience (Wilson, 1998:86–87).[10]

See developmental biology and developmental psychology.

It corresponds to Aristotle's material cause.[8]

Causal relationships

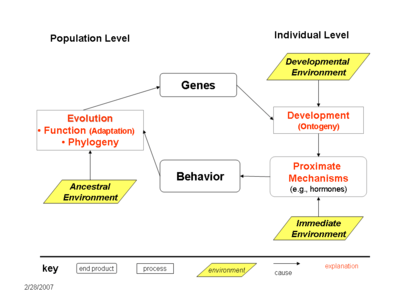

The figure shows the causal relationships among the categories of explanations. The left-hand side represents the evolutionary explanations at the species level; the right-hand side represents the proximate explanations at the individual level. In the middle are those processes' end products—genes (i.e., genome) and behaviour, both of which can be analyzed at both levels.

Evolution, which is determined by both function and phylogeny, results in the genes of a population. The genes of an individual interact with its developmental environment, resulting in mechanisms, such as a nervous system. A mechanism (which is also an end-product in its own right) interacts with the individual's immediate environment, resulting in its behaviour.

Here we return to the population level. Over many generations, the success of the species' behaviour in its ancestral environment—or more technically, the environment of evolutionary adaptedness (EEA) may result in evolution as measured by a change in its genes.

In sum, there are two processes—one at the population level and one at the individual level—which are influenced by environments in three time periods.

Examples

Vision

Four ways of explaining visual perception:

- Function: To find food and avoid danger.

- Phylogeny: The vertebrate eye initially developed with a blind spot, but the lack of adaptive intermediate forms prevented the loss of the blind spot.

- Causation: The lens of the eye focuses light on the retina.

- Development: Neurons need the stimulation of light to wire the eye to the brain (Moore, 2001:98–99).

Westermarck effect

Four ways of explaining the Westermarck effect, the lack of sexual interest in one's siblings (Wilson, 1998:189–196):

- Function: To discourage inbreeding, which decreases the number of viable offspring.

- Phylogeny: Found in a number of mammalian species, suggesting initial evolution tens of millions of years ago.

- Mechanism: Little is known about the neuromechanism.

- Ontogeny: Results from familiarity with another individual early in life, especially in the first 30 months for humans. The effect is manifested in nonrelatives raised together, for instance, in kibbutzs.

Use of the four-question schema as "periodic table"

Konrad Lorenz, Julian Huxley and Niko Tinbergen were familiar with both conceptual categories (i.e. the central questions of biological research: 1. - 4. and the levels of inquiry: a. - g.), the tabulation was made by Gerhard Medicus.[11] The tabulated schema is used as the central organizing device in many animal behaviour, ethology, behavioural ecology and evolutionary psychology textbooks (e.g., Alcock, 2001) . One advantage of this organizational system, what might be called the "periodic table of life sciences," is that it highlights gaps in knowledge, analogous to the role played by the periodic table of elements in the early years of chemistry.

| 1. Mechanism | 2. Ontogeny | 3. Function | 4. Phylogeny | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a. Molecule | ||||

| b. Cell | ||||

| c. Organ | ||||

| d. Individual | ||||

| e. Family | ||||

| f. Group | ||||

| g. Society |

This "biopsychosocial" framework clarifies and classifies the associations between the various levels of the natural and social sciences, and it helps to integrate the social and natural sciences into a "tree of knowledge" (see also Nicolai Hartmann's "Laws about the Levels of Complexity"). Especially for the social sciences, this model helps to provide an integrative, foundational model for interdisciplinary collaboration, teaching and research (see The Four Central Questions of Biological Research Using Ethology as an Example – PDF).

Notes and references

- MacDougall-Shackleton, Scott A. (2011-07-27). "The levels of analysis revisited". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 366 (1574): 2076–2085. doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0363. PMC 3130367. PMID 21690126.

- Daly, M & Wilson, M. (1983). Sex, evolution, and behaviour. Brooks-Cole.

- p411 in Tinbergen, Niko (1963) "On Aims and Methods in Ethology," Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie, 20: 410–433.

- Nikolaas Tinbergen

- Nikolaas Tinbergen, ethology, Cartwright 2000:10; Buss 2004:12)

- Nikolaas Tinbergen

- Nikolaas Tinbergen

- Hladký, V. & Havlíček, J. (2013). Was Tinbergen an Aristotelian? Comparison of Tinbergen's Four Whys and Aristotle's Four Causes. Human Ethology Bulletin, 28(4), 3-11

- "Phylogeny" often emphasizes the evolutionary genealogical relationships among species (Alcock 2001:492; Mayr, 2001:289) as distinct from the categories of explanations. Although the categories are more relevant in a conceptual discussion, the traditional term is retained here.

- "Biased learning" is not necessarily limited to the developmental period.

- Mapping Transdisciplinarity in Human Sciences. In: Janice W. Lee (Ed.) Focus on Gender Identity. New York, 2005, Nova Science Publishers, Inc.

References

- Alcock, John (2001) Animal Behaviour: An Evolutionary Approach, Sinauer, 7th edition. ISBN 0-87893-011-6.

- Buss, David M., Martie G. Haselton, Todd K. Shackelford, et al. (1998) "Adaptations, Exaptations, and Spandrels," American Psychologist, 53:533–548. http://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/comm/haselton/webdocs/spandrels.html

- Buss, David M. (2004) Evolutionary Psychology: The New Science of the Mind, Pearson Education, 2nd edition. ISBN 0-205-37071-3.

- Cartwright, John (2000) Evolution and Human Behaviour, MIT Press, ISBN 0-262-53170-4.

- Krebs, J.R., Davies N.B. (1993) An Introduction to Behavioural Ecology, Blackwell Publishing, ISBN 0-632-03546-3.

- Lorenz, Konrad (1937) Biologische Fragestellungen in der Tierpsychologie (I.e. Biological Questions in Animal Psychology). Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie, 1: 24–32.

- Mayr, Ernst (2001) What Evolution Is, Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-04425-5.

- Gerhard Medicus. "Tinbergen's four questions in behavioural Anthropology" (pdf).

- Gerhard Medicus (2017) Being Human – Bridging the Gap between the Sciences of Body and Mind. Berlin: VWB 2015, ISBN 978-3-86135-584-7

- Nesse, Randolph M (2013) "Tinbergen's Four Questions, Organized," Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 28:681-682.

- Moore, David S. (2001) The Dependent Gene: The Fallacy of 'Nature vs. Nurture', Henry Holt. ISBN 0-8050-7280-2.

- Pinker, Steven (1994) The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language, Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-06-097651-9.

- Tinbergen, Niko (1963) "On Aims and Methods of Ethology," Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie, 20: 410–433.

- Wilson, Edward O. (1998) Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge, Vintage Books. ISBN 0-679-76867-X.

External links

Diagrams

Derivative works

- On aims and methods of cognitive ethology (pdf) by Jamieson and Bekoff.