Timeline of therizinosaur research

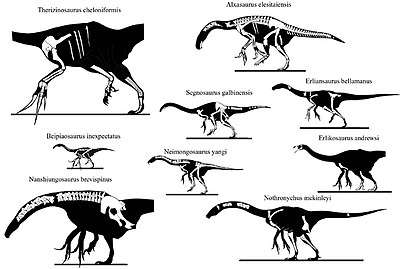

The timeline of therizinosaur research is a chronological listing of events in the history of paleontology focused on therizinosaurs. They were unusually long-necked, pot-bellied, and large-clawed herbivorous theropods most closely related to birds. The early history of therizinosaur research occurred in three phases. The first phase was the discovery of scanty and puzzling fossils in Asia by the Central Asiatic Expeditions of the 1920s and Soviet-backed research in the 1950s. This phase resulted in the discovery of the Therizinosaurus cheloniformis type specimen. Soviet paleontologist Evgeny Maleev interpreted these unusual remains as belonging to some kind of gigantic turtle.

The second major phase of therizinosaur research followed the discovery of better preserved remains in the 1970s by collaborative research between the Soviets and Mongolians. These finds revealed the true nature of therizinosaurs as bizarre dinosaurs. However, the exact nature and classification of therizinosaurs within Dinosauria was controversial as was their paleobiology. When Rozhdestventsky first reinterpreted therizinosaurs as dinosaurs he argued that they were unusual theropods that may have used their clawed arms to break open termite mounds or collect fruit. Osmolska and Roniewicz also considered therizinosaurs to be theropods.

In 1979, Altangerel Perle named the new species Segnosaurus galbinensis, which although he recognized was an unusual theropod, he did not recognize as a therizinosaur. Consequently, he named the new family Segnosauridae and, in 1980, Segnosauria. Two years later, Perle recognized commonalities between Therizinosaurus and segnosaurs, reclassifying the former as a member of the latter. From hereout therizinosaur research was considered "segnosaur" research. Perle himself thought that his "segnosaurs" were semi-aquatic fish-eaters. However, in the early 1990s, researchers like Rinchen Barsbold and Teresa Maryańska cast doubt on the connection between therizinosaurs and segnosaurs altogether.

Nevertheless, the description Alxasaurus elsitaiensis provided more evidence for a close relationship between the therizinosaurs and "segnosaurs" and led to a revision of their classification. The discovery of this and other primitive therizinosaurs in China formed the beginnings of the third major wave of therizinosaur research. That same year Russell and Russell reinterpreted therizinosaurs as herbivorous foragers like mammalian chalicotherium. Other significant finds of the 1990s include therizinosaur eggs with embryos preserved inside and the first known therizinosaur with feathers, Beipiaosaurus, which was described from China in 1999.

20th century

1950s

- Evgeny Maleev described the new genus and species Therizinosaurus cheloniformis. from the Nemegt Formation He interpreted it as a gigantic turtle. Maleev also named the family Therizinosauridae to contain this species.[1]

1960s

- Zakharov described and named the ichnogenus Macropodosaurus, which is represented by a series of four-toed footprints.[2]

1970s

- Rozhdestventsky first proposed the idea that therizinosaurids were actually theropod dinosaurs. He thought they used their large claws to tear open termite mounds or collect fruit from trees.[3]

- Osmolska and Roniewicz also interpreted Therizinosaurus as a carnosaur theropod.[4]

- Barsbold proposed the Deinonychosauria and included Therizinosaurus as a member.[5]

- In another paper during the same year, Barsbold referred a shoulder and forearm found in the same strata as the Therizinosaurus type specimen to that genus because of the resemblance between the specimens claws. He observed that the anatomy of the arm and shoulder remains suggested that it belonged to a theropod dinosaur. Barsbold also remarked on similarities it shared with Deinocheirus, another mysterious dinosaur from the same rock unit.[6]

- Dong described the new genus and species Nanshiungosaurus brevispinus based on a vertebral column and pelvis. He interpreted Nanshiungosaurus as a new genus of dwarf sauropods. He also described the new species Chilantaisaurus zheziangensis but interpreted it as a carnosaur.[7]

- Perle described the new genus and species Segnosaurus galbinensis based on mostly complete limbs and girdles. He erected a new family, the Segnosauridae, for this unusual dinosaur. He tentatively regarded it as a theropod.[8]

1980s

- Barsbold and Perle named the Segnosauria and described the new genus and species Erlikosaurus andrewsi. They also described in brief detail an unknown segnosaur. Barsbold and Perle thought segnosaurs were slow, semi-aquatic animals.[9]

- Perle redescribed the holotype of Erlikosaurus but this time in more detail and mispelled Erlicosaurus.[10]

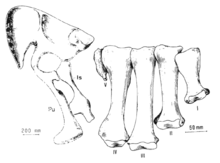

- Perle reported an unusual partial four-toed hind limb from Hermiin Tsav, Nemegt Formation. Because this partial leg was found not far from where Barsbold reported the shoulder and humerus he referred to Therizinosaurus, Perle thought that his specimen also probably belonged to that taxon. Since this leg was similar to those of segnosaurs, he classified Therizinosaurus as a segnosaur.[11]

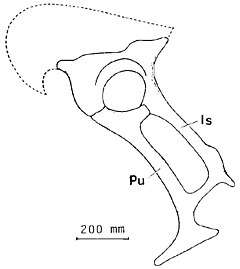

- Barsbold described the new genus and species Enigmosaurus mongoliensis based on a partial pelvis from the previously unknown segnosaur. Barsbold regarded Enigmosaurus as so unusual that he gave it its own family, the Enigmosauridae.[12]

- Paul suggested that segnosaurs shared an evolutionary relationship with prosauropods and ornithischians. He thought this implied that they were probably herbivores.[13]

- Gauthier considered segnosaurs to be relatives of sauropodomorphs.[14]

- Sereno also followed this new interpretation of segnosaurs.[15]

1990s

- Barsbold and Maryanska reinterpreted the sauropod Nanshiungosaurus and the carnosaur Chilantaisaurus as segnosaurs. They agreed with Perle that the partial hind limb from Hermiin Tsav he described in 1982 was segnosaurian, but casted doubt with his referral of it to Therizinosaurus, and therefore with his subsequent conclusion that Therizinosaurus was a segnosaur. Barsbold and Maryanska also disagreed with previous researchers who classified Deinocheirus as a segnosaur.[16]

- David B. Norman considered Therizinosaurus to be a theropod of uncertain classification.[17]

- A collaborative expedition between Chinese and Japanese scientists discovered the type specimen of the new segnosaur species. In addition, Dong named the Segnosaurischia to place segnosaurs on an equal rank with Saurischia and Ornithischia.[18]

- Russel and Dong described the new genus and species Alxasaurus elsitaiensis. They considered it distinct enough to warrant its own family, the Alxasauridae. They pointed out similar anatomical traits in the anatomy of the hand of the partial forlimb Barsbold referred to Therizinosaurus in 1976 and those of segnosaurs. They concluded that therizinosaurids and segnosaurids were theropods and almost identical in traits, and synonymized the Therizinosauridae and Segnosauridae, with the former having nomenclatural priority and coined the superfamily Therizinosauroidea to contain Alxasaurus and its family. The relative completeness of the specimens concluded the debate on whether or not segnosaurs were theropods in the affirmative.[19]

- Russell and Russell noticed that segnosaurs had similar body plans to chalicotheres and ground sloths and concluded that they may have used their large forelimbs to forage in a similar manner.[20]

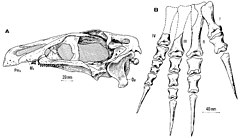

- Clark and others redescribed the skull of Erlikosaurus. They found more evidence that segnosaurs were theropods and classified them as maniraptorans.[21]

- Nessov speculated that segnosaurs may have hung from trees using their large claws like sloths do and fed on wasp nests. He reported the discovery of segnosaur remains in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.[22]

- Currie attributed some Late Cretaceous eggs and their embryos from the Nanchao Formation of Henan, China to segnosaur dinosaurs. These spherical eggs still preserve the fossilized remains of their developing embryos.

- In a second paper, Currie attributed another kind of fossil egg from an entirely different oofamily to segnosaurs. Unlike the spherical eggs of his first paper, these huge "elongated" eggs are classified as members of the Elongatoolithidae and could reach lengths of up to 50 cm.

- Manning and others did not agree with Currie's referral of elongatoolithid eggs to segnosaurs.[23]

- Dong and Yu described the new species "Nanshiungosaurus bohlini" discovered during the 1992 Sino-Japanese expedition, and coined the Nanshiungosauridae to contain it and Nanshiungosaurus.[24]

- Rusell coined the Therizinosauria in order to contain all segnosaurs. This new infraorder was composed of Therizinosauroidea and the more advanced Therizinosauridae. With this, the terms segnosaur and Segnosauria became synonyms to therizinosaur and Therizinosauria, respectively.[25]

- Zhao and Xu reported the existence of a possible therizinosaur dentary dating all the way back to the Early Jurassic.[26]

- Xu, Tang, and Wang described the new genus and species Beipiaosaurus inexpectus. The type specimen actually preserves impressions of the animal's feathered integument. It was also the oldest known therizinosaur.[27]

- Carpenter reported that the embryos Currie considered therizinosaurian had teeth in their premaxillae, unlike any known member of the group. This could be evidence that the egglayer was actually primitive for a therizinosaur. He also did not confirm Currie's referral of elongatoolithid eggs to therizinoasaurs.[28]

21st century

2000s

- Manning and others observed that the embryos identified by Currie in 1996 as therizinosaurian had "an unusual pattern of tooth replacement in which a slender, elongate tooth is replaced by a symmetrical, denticulate tooth". Contrary to Carpenter's claim in 1999, Manning and his colleagues reported the embryos premaxillae as toothless.[29]

- Xu, Zhao, and Clark described the new genus and species Eshanosaurus deguchiianus based on the Early Jurassic dentary. This species was the probably oldest known therizinosaur.[30]

- Kirkland and Wolfe described the new genus and species Nothronychus mckinleyi. This was the first definitive therizinosaurid discovered outside of Asia. They also found that Eshanosaurus had a similar dentition to prosauropods.[31]

- Zhang and others described the new genus and species Neimongosaurus yangi.[32]

- Xu and others described the new genus and species Erliansaurus bellamanus.[33]

- Kirkland and colleagues briefly reported and described primitive remains of therizinosaurs found in Utah.[34]

- The same team made comparisons with braincases found among the remains and that of Nothronychus mckinleyi.[35]

- Lindsay Zanno continue with these short descriptions but this time focused on forelimb elements.[36]

- Zanno discussed in more detail these elements in her Ph.D.[37]

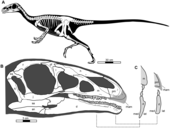

- Kirkland and others described the primitive new genus and species Falcarius utahensis based on the multiple remains previously described.[38]

- Zanno and Erickson briefly discussed the growth of Falcarius which was represented by adult and juvenile specimens.[39]

- Zanno formally published and described the pectoral anatomy of Falcarius.[40]

- Bursh reported the inferred range of motion in the therizinosaurids Neimongosaurus, which was very pronounced and circular.[41]

- Sennikov re-examined Macropodosaurus and concluded that a therizinosaurid-grade dinosaur made those tracks, suggesting a possible plantigrade stance. He also considered these tracks to be more associated with therizinosaurids.[42]

- Li and others described the new genus and species Suzhousaurus megatherioides.[43]

- Kundrát with colleagues described in detail the embryos from the Nanchao Formation.[44]

2010s

- Zanno described in detail the osteology of Falcarius based on numerous specimens.[49]

- Zanno conducted the most detailed phylogenetic analysis of the Therizinosauria to that point. She cited the inaccessibility, damage, potential loss of holotype specimens, scarcity of cranial remains, and fragmentary specimens with few overlapping elements as the most significant obstacles to resolving the evolutionary relationships within the group. She also revised Therizinosauroidea to exclude Falcarius and retained it in the wider clade Therizinosauria, which became the senior synonym of Segnosauria.[50]

- Smith and team described in detail the braincase anatomy of Falcarius.[51]

- Qian and colleagues discussed the affinities of Chilantaisaurus zheziangensis and noted that is actually a therizinosaurid. Tiantaisaurus was briefly mentioned but not officially named.[52]

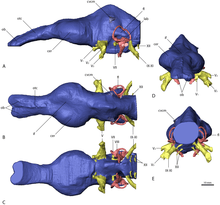

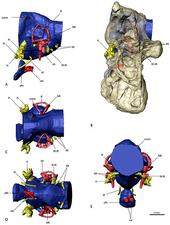

- Lautenschlager with colleagues reconstructed the cranial cavities of Erlikosaurus via CT scans and noted a complex ear and brain structure that may apply to other therizinosaurids.[53]

- Senter with others described the new genus and species Martharaptor greenriverensis.[54]

- Fiorillo and Adams described four-toed footprints from the Cantwell Formation. The morphology is similar to therizinosaurid feet but slighlty different from Macropodosaurus. Nevertheless, they attributed these tracks to therizinosaurids.[55]

- Lautenschlager performed digital reconstructions for the cranial musculature in Erlikosaurus and found the bite force of Edmontosaurus being greater than that for the former. The lesser bite force for Erlikosaurus better served in stripping and cropping leaves, rather than active mastication.[56]

- Using the complete holotype skull of Erlikosaurus, Lautenschlager and colleagues noted that the keratinous beak in therizinosaurs and most other beaked theropods was an adaption that might have helped to enhance cranial stability by mitigating the stress and strain experienced by the skull during feeding.[57]

- Pu with colleagues described the new primitive genus and species Jianchangosaurus yixianensis. They regarded this genus along with Falcarius was the most primitive.[58]

- Kobayashi and colleagues reported an exceptional nesting ground site of therizinosaurid dinosaurs at the Javkhlant Formation, which contained at least 17 dendroolithid egg clutches.[59]

- Lautenschlager concluded that the claws of most therizinosaurs were more effective when piercing or pulling down vegetation but not for digging. He could neither confirm nor disregard that the hand claws could have been fully used for sexual display, self-defense, intraspecific competition, mate-gripping during mating or grasping stabilization when foraging.[60]

- The osteology and taphonomy of Nothronychus was fully described by Hedrick and colleagues, providing anatomical considerations for other therizinosaurids.[61]

- Gierlinski reported Macropodosaurus footprints in Poland.[62]

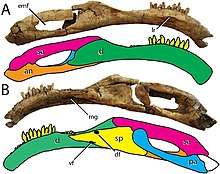

- Zanno with colleagues redescribed the complex lower jaws and dentition of Segnosaurus and noticed a niche partitioning between this taxon and Erlikosaurus.[63]

- Sues and Averianov described extensive remains of therizinosauroid and potentially therizinosaurid remains from the Bissekty Formation.[64]

- Lautenschlager concluded the evolutionary trends in jaw mechanics of therizinosaurs suffered a change from higher bite forces and robust lower jaws in early members to lesser ones in derived therizinosaurs.[65]

- Masrour with colleagues reported Macropodosaurus footprints on Cretaceous strata in Morocco.[66]

- The holotype braincase of Nothronychus mckinleyi was re-analyzed by Smith with colleagues finding similar traits and capacities to Erlikosaurus.[67]

- Fiorillo and team found more therizinosaurid tracks from the Cantwell Formation but this time in association with hadrosaurid footprints. They were the first authors providing photographs of the holotype Erlikosaurus feet.[68]

- Hartman with colleagues performed a large phylogenetic analysis for the Therizinosauria and other theropod groups. This analysis was strongly based on the 2010 work of Zanno.[69]

- Yao and colleagues described the possible new genus and species Lingyuanosaurus sihedangensis.[70]

- Liao and Xu redescribed the holotype skull of Beipiaosaurus in detail, noting new unique cranial traits for the genus.[71]

- Ali Nabavizadeh concluded that most therizinosaurs were mainly orthal feeders (moving their jaws up and down and not to the sides) and raised their jaws isognathously whereby the upper and lower teeth of each side contacted each other at once.[72]

- Button and Zanno found that Segnosaurus had gracile skulls and relatively low bite forces, indicating a food processing in the gut. Erlikosaurus had features associated with extensive processing such as the lower jaws or dentition and therefore, the food processing was in the mouth.[73]

- The Javkhlant Formation nesting site was formally described in 2019 by Kohei Tanaka and colleagues concluding that egg clutches were covered in organic-rich material during incubation and colonial nesting first evolved in non-avian dinosaur to increase hatching success.[74]

References

- Maleev, E. A. (1954). "Noviy cherepachoobrazhniy yashcher v Mongolii" [New turtle−like reptile in Mongolia]. Priroda (3): 106−108. Translated paper

- Zakharov, S. A. (1964). "On the Cenomanian dinosaur, the tracks of which were found in the Shirkent River Valley". In Reiman, V. M. (ed.). Paleontology of Tajikistan (in Russian). Dushanbe: Academy of Sciences of Tajik S.S.R. Press. pp. 31−35.

- Rozhdestvensky, A. K. (1970). "On the gigantic claws of mysterious Mesozoic reptiles". Paleontologicheskii Zhurnal (in Russian) (1): 131–141.

- Osmólska, H.; Roniewicz, E. (1970). "Deinocheiridae, a new family of theropod dinosaurs" (PDF). Palaeontologica Polonica (21): 5−19.

- Barsbold, R. (1976). "On the evolution and systematics of the late Mesozoic dinosaurs". Trudy – Sovmestnaya Sovetsko-Mongol'skaya Paleontologicheskaya Ekspeditsiya (in Russian). 3: 68–75.

- Barsbold, R. (1976). "New data on Therizinosaurus (Therizinosauridae, Theropoda)". Joint Soviet-Mongolian Paleontological Expedition (in Russian). 3: 76–92.

- Dong, Z. (1979). "Cretaceous dinosaur fossils in southern China" [Cretaceous dinosaurs of the Huanan (south China)]. In Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology; Nanjing Institute of Paleontology (eds.). Mesozoic and Cenozoic Redbeds in Southern China (in Chinese). Beijing: Science Press. pp. 342−350. Translated paper

- Perle, A. (1979). "Segnosauridae — novoe semejstvo teropod iz pozdnego mela Mongolii" [Segnosauridae — a new family of theropods from the Late Cretaceous of Mongolia]. Transactions of the Joint Soviet-Mongolian Paleontological Expedition (in Russian). 8: 45−55. Translated paper

- Barsbold, R.; Perle, A. (1980). "Segnosauria, a new suborder of carnivorous dinosaurs" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 25 (2): 190−192.

- Perle, A. (1981). "Novyy segnozavrid iz verkhnego mela Mongolii" [New Segnosauridae from the Upper Cretaceous of Mongolia]. Transactions of the Joint Soviet-Mongolian Paleontological Expedition (in Russian). 15: 50−59. Translated paper

- Perle, A. (1982). "A hind limb of Therizinosaurus from the Upper Cretaceous of Mongolia". Problems in Mongolian Geology (in Russian). 5: 94−98. Translated paper

- Barsbold, R. (1983). "Хищные динозавры мела Монголии" [Carnivorous dinosaurs from the Cretaceous of Mongolia] (PDF). Transactions of the Joint Soviet-Mongolian Paleontological Expedition (in Russian). 19: 89. Translated paper

- Paul, G. S. (1984). "The segnosaurian dinosaurs: relics of the prosauropod-ornithischian transition?". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 4 (4): 507−515. doi:10.1080/02724634.1984.10012026. ISSN 0272-4634. JSTOR 4523011.

- Gauthier, J. (1986). "Saurischian monophyly and the origin of birds". Memoirs of the California Academy of Sciences. 8: 45. Archived from the original on 2019-08-16.

- Sereno, P. (1989). "Prosauropod monophyly and basal sauropodomorph phylogeny". Abstract of Papers. Forty-Ninth Annual Meeting Society of Vertebrate Paleontology. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 9 (3 Supplement). p. 39A. ISSN 0272-4634. JSTOR 4523276.

- Barsbold, R.; Maryańska, T. (1990). "Saurischia Sedis Mutabilis: Segnosauria". In Weishampel, D. B.; Osmolska, H.; Dodson, P. (eds.). The Dinosauria (1st ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 408−415. ISBN 9780520067271.

- Norman, D. B. (1990). "Problematic Theropoda: Coelurosauria". In Weishampel, D. B.; Osmolska, H.; Dodson, P. (eds.). The Dinosauria (1st ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 280−305. ISBN 9780520067271.

- Dong, Z. (1992). Dinosaurian Faunas of China. Beijing: China Ocean Press. p. 187. ISBN 3-540-52084-8.

- Russell, D. A.; Dong, Z. (1993). "The affinities of a new theropod from the Alxa Desert, Inner Mongolia, People's Republic of China". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 30 (10): 2107−2127. Bibcode:1993CaJES..30.2107R. doi:10.1139/e93-183.

- Russell, D. A.; Russell, D. E. (1993). "Mammal-dinosaur convergence". National Geographic Research. 9: 70–79. ISSN 8755-724X.

- Clark, J. M.; Perle, A.; Norell, M. (1994). "The skull of Erlicosaurus andrewsi, a Late Cretaceous Segnosaur (Theropoda, Therizinosauridae) from Mongolia". American Museum Novitates. 3115: 1−39. hdl:2246/3712.

- Nessov, L. A. (1995). Dinosaurs of northern Eurasia: new data about assemblages, ecology, and paleobiogeography (in Russian). Saint Petersburg: Institute of Earth Crust, Saint Petersburg University. p. 49. Translated paper

- Manning, T. W.; Joysey, K. A.; Cruickshank, A. R. I. (1997). "Observations of microstructures within dinosaur eggs from Henan Province, Peoples' Republic of China". In Wolberg, D. L.; Stump, E.; Rosenberg, R. D. (eds.). Dinofest International: Proceedings of a Symposium Held at Arizona State University. Pennsylvania: Academy of Natural Sciences. pp. 287−290.

- Dong, Z.; You, H. (1997). "A new segnosaur from Mazhongshan Area, Gansu Province, China". In Dong, Z. M. (ed.). Sino-Japanese Silk Road Dinosaur Expedition. Beijing: China Ocean Press,. pp. 90−95.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)

- Russell, D. A. (1997). "Therizinosauria". In Currie, P. J.; Padian, K. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 729−730. ISBN 978-0-12-226810-6.

- Zhao, X.; Xu, X. (1998). "The oldest coelurosaurian". Nature. 394 (6690): 234–235. Bibcode:1998Natur.394..234Z. doi:10.1038/28300.

- Xu, X.; Tang, Z.-L.; Wang, X. L. (1999). "A therizinosauroid dinosaur with integumentary structures from China". Nature. 339 (6734): 350−354. Bibcode:1999Natur.399..350X. doi:10.1038/20670. ISSN 1476-4687.

- Carpener, K. (1999). "The Embryo and Hatching". Eggs, Nests, and Baby Dinosaurs: A Look at Dinosaur Reproduction (Life of the Past). Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 209. ISBN 9780253334978.

- Manning, T. W.; Joysey, K. A.; Cruickshank, A. R. I. (2000). "In ovo tooth replacement in a therizinosauroid dinosaur". In Bravo, A. M.; Reyes, T. (eds.). Extended Abstracts, First International Symposium on Dinosaur Eggs and Babies. Spain: Impremta Provincial de la Diputació Lleida, Isona i Conca Dellà. pp. 129−134.

- Xu, X.; Zhao, X.; Clark, J. M. (2001). "A new therizinosaur from the Lower Jurassic lower Lufeng Formation of Yunnan, China". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 21 (3): 477−483. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2001)021[0477:ANTFTL]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 20061976.

- Kirkland, J. I.; Wolfe, D. G. (2001). "First definitive therizinosaurid (Dinosauria; Theropoda) from North America". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 21 (3): 410−414. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2001)021[0410:fdtdtf]2.0.co;2. JSTOR 20061971.

- Zhang, X.-H.; Xu, X.; Zhao, Z.-J.; Sereno, P. C.; Kuang, X.-W.; Tan, L. (2001). "A long-necked therizinosauroid dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous Iren Dabasu Formation of Nei Mongol, People's Republic of China" (PDF). Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 39 (4): 282−290.

- Xu, X.; Zhang, Z.-H.; Sereno, P. C.; Zhao, X.-J.; Kuang, X.-W.; Han, J.; Tan, L. (2002). "A new therizinosauroid (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous Iren Dabasu Formation of Nei Mongol" (PDF). Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 40: 228−240.

- Kirkland, J. I.; Zanno, L. E.; DeBlieux, D. D.; Sampson, S. D. (2004). "A new, basal-most therizinosauroid (Theropoda: Maniraptora) from Utah demonstrates a pan-Laurasian distribution for Early Cretaceous (Barremian) therizinosauroids". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 24 (supp. 3): 78A. doi:10.1080/02724634.2004.10010643.

- Smith, D. K.; Kirkland, J. I.; Sanders, R. K.; Zanno, L. E.; DeBlieux, D. D. (2004). "A comparison of North American therizinosaur (Theropoda: Dinosauria) braincases". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 24 (supp. 3): 114A. doi:10.1080/02724634.2004.10010643.

- Zanno, L. E. (2004). "The pectoral girdle and forelimb of a primitive therizinosauroid (Theropoda: Maniraptora): New information on the phylogenetics and evolution of therizinosaurs". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 24 (supp. 3): 134A. doi:10.1080/02724634.2004.10010643.

- Zanno, L. E. (2004). The Pectoral Girdle and Forelimb of a Primitive Therizinosauroid (Theropoda, Maniraptora) with Phylogenetic and Functional Implications (PhD diss.). Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of Utah.

- Kirkland, J. I.; Zanno, L. E.; Sampson, S. D.; Clark, J. M.; DeBlieux, D. D. (2005). "A primitive therizinosauroid dinosaur from the Early Cretaceous of Utah". Nature. 435 (7038): 84–87. Bibcode:2005Natur.435...84K. doi:10.1038/nature03468. PMID 15875020.

- Zanno, L. E.; Erickson, G. M. (2006). "Ontogeny and life history of Falcarius utahensis, a primitive therizinosauroid from the Early Cretaceous of Utah". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 26 (supp. 3): 143A. doi:10.1080/02724634.2006.10010069.

- Zanno, L. E. (2006). "The pectoral girdle and forelimb of the primitive therizinosauroid Falcarius Utahensis (Theropoda, Maniraptora): analyzing evolutionary trends within Therizinosauroidea". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 26 (3): 636−650. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2006)26[636:tpgafo]2.0.co;2. JSTOR 4524610.

- Burch, S. H. (2006). "The range of motion of the glenohumeral joint of the therizinosaur Neimongosaurus yangi (Dinosauria: Theropoda)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 26 (supp. 3): 46A. doi:10.1080/02724634.2006.10010069.

- Sennikov, A. G. (2006). "Reading segnosaur tracks". Priroda (in Russian). 5: 58−67.

- Li, D.; Peng, C.; You, H.; Lamanna, M. C.; Harris, J. D.; Lacovara, K. J.; Zhang, J. (2007). "A Large Therizinosauroid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Early Cretaceous of Northwestern China". Acta Geologica Sinica (English Edition). 81 (4): 539–549. doi:10.1111/j.1755-6724.2007.tb00977.x. ISSN 1000-9515.

- Kundrát, M.; Cruickshank, A. R. I.; Manning, T. W.; Nudds, J. (2007). "Embryos of therizinosauroid theropods from the Upper Cretaceous of China: diagnosis and analysis of ossification patterns". Acta Zoologica. 89 (3): 231−251. doi:10.1111/j.1463-6395.2007.00311.x.

- Li, D.; You, H.; Zhang, J. (2008). "A new specimen of Suzhousaurus megatherioides (Dinosauria: Therizinosauroidea) from the Early Cretaceous of northwestern China". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 45 (7): 769–779. Bibcode:2008CaJES..45..769L. doi:10.1139/E08-021.

- Lee, Y.-N.; Barsbold, R.; Currie, P. J. (2008). "A short report of Korea-Mongolia International Dinosaur Project (1st and 2nd year)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 28 (supp. 003): 104A–105A. doi:10.1080/02724634.2008.10010459.

- Zanno, L. E.; Gillette, D. D.; Albright, L. B.; Titus, A. L. (2009). "A new North American therizinosaurid and the role of herbivory in predatory dinosaur evolution". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 276 (1672): 3505−3511. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.1029. JSTOR 30244145. PMC 2817200. PMID 19605396.

- Barrett, P. M. (2009). "The affinities of the enigmatic dinosaur Eshanosaurus deguchiianus from the Early Jurassic of Yunnan Province, People's Republic of China". Paleontology. 52 (4): 681−688. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2009.00887.x.

- Zanno, L. E. (2010). "Osteology of Falcarius utahensis (Dinosauria: Theropoda): characterizing the anatomy of basal therizinosaurs". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 158 (1): 196–230. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00464.x.

- Zanno, L. E. (2010). "A taxonomic and phylogenetic re-evaluation of Therizinosauria (Dinosauria: Maniraptora)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 8 (4): 503−543. doi:10.1080/14772019.2010.488045.

- Smith, D. K.; Zanno, L. E.; Sanders, R. K.; Deblieux, D. D.; Kirkland, J. I. (2011). "New information on the braincase of the North American therizinosaurian (Theropoda, Maniraptora) Falcarius utahensis". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 31 (2): 387−404. doi:10.1080/02724634.2011.549442. JSTOR 25835833.

- M.-p. Qian, Z.-y. Zhang, Y. Jiang, Y.-g. Jiang, Y.-j. Zhang, R. Chen, and G.-f. Xing (2012). "Cretaceous therizinosaurs in Zhejiang of eastern China". Journal of Geology. 36 (4): 337−348.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Lautenschlager, S.; Emily, J. R.; Perle, A.; Zanno, L. E.; Lawrence, M. W. (2012). "The Endocranial Anatomy of Therizinosauria and Its Implications for Sensory and Cognitive Function". PLOS ONE. 7 (12): e52289. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...752289L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0052289. PMC 3526574. PMID 23284972.

- Senter, P.; Kirkland, J. I.; Deblieux, D. D. (2012). "Martharaptor greenriverensis, a New Theropod Dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of Utah". PLOS ONE. 7 (8): e43911. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...743911S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0043911. PMC 3430620. PMID 22952806.

- Fiorillo, A. R; Adams, T. L. (2012). "A Therizinosaur Track from the Lower Cantwell Formation (upper Cretaceous) of Denali National Park, Alaska". PALAIOS. 27 (6): 395−400. Bibcode:2012Palai..27..395F. doi:10.2110/palo.2011.p11-083r.

- Lautenschlager, S. (2013). "Cranial myology and bite force performance of Erlikosaurus andrewsi : a novel approach for digital muscle reconstructions". Journal of Anatomy. 222 (2): 260−272. doi:10.1111/joa.12000. PMC 3632231. PMID 23061752.

- Lautenschlager, S.; Witmer, L. M.; Perle, A.; Rayfield, E. J. (2013). "Edentulism, beaks, and biomechanical innovations in the evolution of theropod dinosaurs". PNAS. 110 (51): 20657−20662. Bibcode:2013PNAS..11020657L. doi:10.1073/pnas.1310711110. JSTOR 23761610. PMC 3870693. PMID 24297877.

- Pu, H.; Kobayashi, Y.; Lü, J.; Xu, L.; Wu, Y.; Chang, H.; Zhang, J.; Jia, S. (2013). "An Unusual Basal Therizinosaur Dinosaur with an Ornithischian Dental Arrangement from Northeastern China". PLOS ONE. 8 (5): e63423. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0063423. PMC 3667168. PMID 23734177.

- "First record of a dinosaur nesting colony from Mongolia reveals nesting behavior of therizinosauroids". Hokkaido University. 2013.

- Lautenschlager, S. (2014). "Morphological and functional diversity in therizinosaur claws and the implications for theropod claw evolution". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 28 (1785): 20140497. doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.0497. PMC 4024305. PMID 24807260.

- Hedrick, B. P.; Zanno, L. E.; Wolfe, D. G.; Dodson, P. (2015). "The Slothful Claw: Osteology and Taphonomy of Nothronychus mckinleyi and N. graffami (Dinosauria: Theropoda) and Anatomical Considerations for Derived Therizinosaurids". PLOS ONE. 10 (6): e0129449. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1029449H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0129449. PMC 4465624. PMID 26061728.

- Gierliński, G. D (2015). "New Dinosaur Footprints from the Upper Cretaceous of Poland in the Light of Paleogeographic Context". Ichnos. 22 (3–4): 220−226. doi:10.1080/10420940.2015.1063489.

- Zanno, L. E.; Tsogtbaatar, K.; Chinzorig, T.; Gates, T. A. (2016). "Specializations of the mandibular anatomy and dentition of Segnosaurus galbinensis (Theropoda: Therizinosauria)". PeerJ. 4: e1885. doi:10.7717/peerj.1885. PMC 4824891. PMID 27069815.

- Sues, H.-D.; Averianov, A. (2016). "Therizinosauroidea (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of Uzbekistan". Cretaceous Research. 59: 155−178. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2015.11.003.

- Lautenschlager, S. (2017). "Functional niche partitioning in Therizinosauria provides new insights into the evolution of theropod herbivory". Palaeontology. 60 (3): 375−387. doi:10.1111/pala.12289.

- Masrour, M.; Lkebir, N.; Pérez-Lorente, F. (2017). "Anza palaeoichnological site. Late Cretaceous. Morocco. Part II. Problems of large dinosaur trackways and the first African Macropodosaurus trackway". Journal of African Earth Sciences. 134: 776−793. Bibcode:2017JAfES.134..776M. doi:10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2017.04.019. ISSN 1464-343X.

- Smith, D. K.; Sanders, R. K.; Wolfe, D. G. (2018). "A re-evaluation of the basicranial soft tissues and pneumaticity of the therizinosaurian Nothronychus mckinleyi (Theropoda; Maniraptora)". PLOS ONE. 13 (7): e0198155. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0198155. PMC 6067709. PMID 30063717.

- Fiorillo, A. R.; McCarthy, P. J.; Kobayashi, Y.; Tomsich, C. S.; Tykoski, R. S.; Lee, Y.-N.; Tanaka, T.; Noto, C. R. (2018). "An unusual association of hadrosaur and therizinosaur tracks within Late Cretaceous rocks of Denali National Park, Alaska". Scientific Reports. 8 (11706). doi:10.1038/s41598-018-30110-8. PMC 6076232. PMID 30076347.

- Hartman, S.; Mortimer, M.; Wahl, W. R.; Lomax, D. R.; Lippincott, J.; Lovelace, D. M. (2019). "A new paravian dinosaur from the Late Jurassic of North America supports a late acquisition of avian flight". PeerJ. 7: e7247. doi:10.7717/peerj.7247. PMC 6626525. PMID 31333906.

- Xi Yao; Chun-Chi Liao; Corwin Sullivan; Xing Xu (2019). "A new transitional therizinosaurian theropod from the Early Cretaceous Jehol Biota of China". Scientific Reports. 9: Article number 5026. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-41560-z. PMC 6430829. PMID 30903000.

- Liao, C.-C.; Xu, X. (2019). "Cranial osteology of Beipiaosaurus inexpectus (Theropoda: Therizinosauria)". Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 57 (2): 117–132. doi:10.19615/j.cnki.1000-3118.190115.

- Nabavizadeh, A. (2019). "Cranial musculature in herbivorous dinosaurs: a survey of reconstructed anatomical diversity and feeding mechanisms". The Anatomical Record: 32. doi:10.1002/ar.24283. PMID 31675182.

- Button, D. J.; Zanno, L. E. (2019). "Repeated evolution of divergent modes of herbivory in non-avian dinosaurs". Current Biology. 30 (1): 158−168.e4. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.10.050. PMID 31813611.

- Tanaka, K.; Kobayashi, Y.; Zelenitsky, D. K.; Therrien, F.; Lee, Y.-N.; Barsbold, R.; Kubota, K.; Lee, H.-J.; Tsogtbaatar, C.; Idersaikhan, D. (2019). "Exceptional preservation of a Late Cretaceous dinosaur nesting site from Mongolia reveals colonial nesting behavior in a non-avian theropod". Geology. 47 (9): 843−847. doi:10.1130/G46328.1.