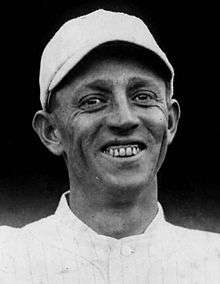

Tilly Walker

Clarence William "Tilly" Walker (September 4, 1887[lower-alpha 1] – September 21, 1959) was an American professional baseball player. After growing up in Limestone, Tennessee, and attending college locally at Washington College, he entered Major League Baseball (MLB). He was a left fielder and center fielder for the Washington Senators, St. Louis Browns, Boston Red Sox and Philadelphia Athletics from 1911 to 1923.

| Tilly Walker | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Outfielder | |||

| Born: September 4, 1887 Telford, Tennessee | |||

| Died: September 21, 1959 (aged 72) Unicoi, Tennessee | |||

| |||

| MLB debut | |||

| June 10, 1911, for the Washington Senators | |||

| Last MLB appearance | |||

| October 6, 1923, for the Philadelphia Athletics | |||

| MLB statistics | |||

| Batting average | .281 | ||

| Home runs | 118 | ||

| Runs batted in | 679 | ||

| Teams | |||

| |||

| Career highlights and awards | |||

| |||

In 1918, he tied Babe Ruth for the home run crown that season. His power output increased for three seasons beginning in 1920. In 1922, he finished second in the league in home runs and he became one of five players to have reached 100 career home runs. He struggled in his final MLB season and was released by Philadelphia. After his MLB career, Walker played for several seasons in the minor leagues. He also managed a minor league team for one season and worked for the Tennessee Highway Patrol.

Early life and career

Walker was born in Telford, Tennessee.[1][lower-alpha 1] His family moved to Limestone, Tennessee, when he was a child.[2] His father, W. N. Walker, was an undertaker and a member of the local county high school board of education.[3][4] Walker later recalled that there was not much to do in Limestone, so he developed his throwing ability by tossing rocks.[2] He pitched and played right field for the baseball team at Washington College in Limestone in the 1908–09 and 1909–10 school years.[5]

Walker's professional baseball career began with the Spartanburg Spartans of the Carolina Association in 1910 and 1911.[6] Hitting for a .390 batting average with Spartanburg in 35 games in 1911, Walker caught the attention of the Washington Senators. The team purchased Walker's contract from Spartanburg and played him in 95 major league games. Walker finished the season with a .278 average, 2 home runs and 12 stolen bases.[1]

Starting the 1912 season with the Senators, he hit .273 through 35 games, but he committed 8 errors.[1] The Senators started that season poorly, so manager Clark Griffith sold his contract to the minor-league Kansas City Blues in an attempt to overhaul his team.[7] Walker said that he had been present when Griffith handed a telegram to a telegraph operator one night. Owing to telegraphy experience from a boyhood job, Walker heard the Morse Code and realized that the telegram was requesting waivers on him. He was sold to the Blues after no major league teams were interested. He considered returning to Limestone as a telegraph operator, but he ultimately went to the Blues.[2]

Walker spent most of 1913 with the Blues, hitting .306 with 6 home runs. He made it back to the major leagues that year with the St. Louis Browns, appearing in 23 games.[1] According to Nellie King, Browns manager Branch Rickey compared Walker to Ty Cobb in terms of ability, saying that they differed only because Cobb displayed more effort.[8]

Middle career

Walker hit .278 with 6 home runs, 78 runs batted in (RBI) and a career-high 29 stolen bases in 151 games during the 1914 season. His offensive totals dropped with the 1915 Browns; he finished with a .269 average, 5 home runs, 49 RBI and 20 steals. Just before the 1916 season, the Boston Red Sox purchased Walker's contract for US$3,500 ($82,234 today).[1]

The purchase of Walker indirectly facilitated the sale of Red Sox star outfielder Tris Speaker to the Cleveland Indians; the Walker deal signaled to Cleveland executives that Boston was looking to trade Speaker, so Cleveland executives began negotiations with the Red Sox that resulted in Speaker's purchase for $55,000.[9] Walker was seen as a good hitter and he had a strong arm, having led the league's outfielders in assists for the two previous seasons. However, he had been criticized for his mood swings and for not being a team player.[10]

Walker earned one of his lowest batting averages (.266) that year, but Boston won the 1916 World Series. In that series, he batted twelve times and earned three hits, including a triple. He played only 106 games in 1917, hitting a career-low .246 for the Red Sox. Before the 1918 season, Walker was sent to the Philadelphia Athletics as the player to be named later in a multiplayer trade for first baseman Stuffy McInnis. He tied Ruth as the league leader in homeruns (11) in 1918.[1] In 1919, Walker and two other American League (AL) players each hit 10 home runs, while Ruth hit 29.[11]

Later career

After the introduction of a new type of ball in 1920, Walker slugged 17 home runs. He registered home run totals of 23 the next year and 37 in 1922.[12] He finished second in the AL in home runs in 1922, ahead of Ruth and trailing Ken Williams by two home runs.[13] Walker passed 100 career home runs that year, becoming one of the first five major league players to reach that milestone.[14] After the 1922 season, Athletics manager Connie Mack opted to prioritize pitching and defense over hitting, so he moved the fences 30 to 40 feet deeper in Philadelphia. Walker struggled under the new conditions and played only 52 games in 1923.[12]

Walker was given an unconditional release from the Athletics in December 1923.[15] He returned to the minor leagues for the 1924 season.[6] Walker spent six years with the Minneapolis Millers, Baltimore Orioles, Toronto Maple Leafs and Greenville Spinners. He hit for double-digit home run totals five times as a minor league player, including a 1928 season in which he hit 33 home runs. The 1929 season was his last; he appeared in only 12 games that year.[6] He spent a year as an umpire in the Piedmont League in 1934.[16] In 1940, he was the manager of the Erwin Mountaineers in the Appalachian League.[6]

Career statistics

In 1421 games over 13 seasons, Walker posted a .281 batting average (1423-for-5067) with 696 runs, 244 doubles, 71 triples, 118 home runs, 679 RBI, 129 stolen bases, 416 bases on balls, .339 on-base percentage and .427 slugging percentage. He finished his career with a .949 fielding percentage playing at all three outfield positions.[1]

Later life

Beginning in 1940, Walker worked as a patrolman for the Tennessee Highway Patrol, stationed in Bristol.[17][18] He made his home in Limestone.[3] In 1959, he died of natural causes at his brother's home in Unicoi, Tennessee.[19] He is buried at Urbana Cemetery in Limestone.[3]

Notes

- Walker sometimes gave his birthplace as Denver, Colorado, and his date of birth as October 8, 1880.[2]

References

- Tillie Walker Statistics and History. Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- Sheridan, J. B. (June 29, 1914). "Walker's pride made him great; he resented release by Griffith". Evening Independent. Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- Brooks, James (2006). Limestone. Arcadia Publishing. pp. 38–39. ISBN 0738543004. Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- Biennial Report of the State Superintendent of Instruction of Tennessee. Nashville: Press of Brandon Printing Company. 1915. p. 30. Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- Brooks, James (2006). Limestone. Arcadia Publishing. pp. 98–99. ISBN 0738543004. Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- "Tillie Walker Minor League Statistics & History". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- "Walker's failure Shanks' chance". The Daily Times. December 26, 1923. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- King, Nelson J. (September 2009). Happiness Is Like a Cur Dog: The Thirty-Year Journey of a Major League Baseball Pitcher and Broadcaster. AuthorHouse. pp. 105–108. ISBN 978-1-4490-2548-9. Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- Brown, Norman (June 29, 1925). "Tillie never played there". St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- Whalen, Thomas J. (April 16, 2011). When the Red Sox Ruled: Baseball's First Dynasty, 1912–1918. Government Institutes. pp. 111–112. ISBN 978-1-56663-902-6. Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- "1919 American League Batting Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- McNeil, William (1997). The King of Swat: An Analysis of Baseball's Home Run Hitters from the Major, Minor, Negro, and Japanese Leagues. McFarland & Company. pp. 39–41. ISBN 0786403624. Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- "1922 American League Batting Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- "Walker of Philadelphia Athletics hit over one hundred home runs". Quebec Daily Telegraph. July 26, 1922. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- "Tillie Walker is dropped by Mack". Evening Independent. December 22, 1923. Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- "TSN Umpire Card: Tilly Walker". Retrosheet. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

- Hayes, Tim (July 20, 2008). "Local legends in the pros: Bristol resident remembers Tilly Walker". Bristol Herald Courier. Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- Batesel, Paul (February 14, 2007). Major League Baseball Players of 1916: A Biographical Dictionary. McFarland. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-7864-2782-6. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

- "Tilly Walker, ex-player, dies". The Pittsburgh Press. September 22, 1959. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tilly Walker. |

- Career statistics and player information from Baseball-Reference, or Baseball-Reference (Minors)

- Tilly Walker at Find a Grave