Ticuna

The Ticuna (also Magüta, Tucuna, Tikuna, or Tukuna[2]) are an indigenous people of Brazil (36,000), Colombia (6,000), and Peru (7,000). They are the most numerous tribe in the Brazilian Amazon.[1]

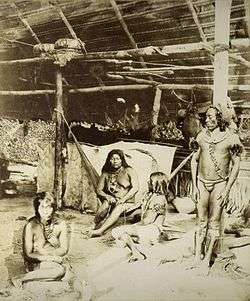

Ticuna people in Amazonas, Brazil, ca. 1865, by Albert Frisch. | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

( | 36,377 (2009)[1] |

| 8,000 (2011)[1] | |

| 6,982 (2007)[1] | |

| Languages | |

| Ticuna[2] | |

| Religion | |

| Shamanism, Christianity | |

History

The Ticuna were originally a tribe that lived far away from the rivers and whose expansion was kept in check by neighboring peoples. Their historical lack of access to waterways and their practice of endogamy has led to the Ticuna being culturally and genetically distinct from other Amazonian tribes.[3] The first contact with outsiders occurred on the colonization of Brazil when a Portuguese fleet exploring the Amazon came into contact with the Ticuna. Sustained contact with the Portuguese and other outsiders began in 1649.[3] Since the Ticuna lived relatively inland compared to other tribes they were less affected by the diseases and violence caused by colonialism, hence why the Ticuna today have the largest population of any Amazonian peoples. When the Europeans initiated warfare with the neighboring tribes, their land, which consisted of islands and coastal areas, was available to the Ticuna. However the Ticuna still suffered greatly, especially in the rubber cultivation that began in the late 19th century where many Ticuna were used for slave labor.[3]

Ticuna as a Brazilian tribe has faced violence from loggers, fishermen, and rubber-tappers entering their lands around the Solimões River. Brazil and Paraguay were in war between 1864–1870, and the Ticuna chose to fight in that war. This depleted their population and the Ticuna were forced out of their Brazilian territories. Four Ticuna people were murdered, 19 were wounded, and ten had disappeared in the 1988 Helmet Massacre. By the 1990s, Brazil formally recognized the Ticunas' right to their lands, thus protecting the Ticuna people, as well as decreasing conflict in the surrounding areas.[1]

Language

Ticuna people speak the Ticuna language, which is usually identified as a language isolate, although it might possibly be related to the extinct Yuri language thus forming the hypothetical Ticuna–Yuri grouping.[4] The Ticuna language was once thought to be an Arawakan language, but this has now been discredited as more likely the Ticuna have adopted many linguistic features due to a long history of interaction with Arawakan-speaking tribes.[3] It is written in the Latin script.[2]

Religion and rituals

Ticuna people historically practiced Shamanism, although with the influence of Christian missionaries since contact Shamans have become rare in all but the most isolated communities.[5] Ta'e was the Ticuna creator god who guarded the earth, while Yo'i and Ip were mythical heroes in Ticuna folklore which helped fight off demons.[5] Depending on different estimates some say that the Ticuna primarily practice ethnic religion, while other estimates say that 30%[6] to 90% are Christian.

The Ticuna practice a coming-of-age ceremony for girls when they reach puberty called a Pelazon. After the girl's first menstruation her whole body is painted black with the clan symbol drawn on her head. All their hair is pulled out and they wear a dress custom made from eagle feathers and snail shells. The girl then must continuously jump over a fire. After four days the girl is considered a woman and is eligible for marriage. Ticuana men and women must marry outside their own clans according to customs. Nowadays the ritual is shorter and less intense as it was historically.[7]

Marriage Patterns

The Ticuna follow the rules of exogamy, in which members of the same moiety are not permitted to marry. In the past, it was common practice for a maternal uncle to marry his niece. Today, however, marriage generally occurs within the same generation. Due to the influence of Catholic missionaries, cross-cousin marriages and polygyny, which were acceptable and common in the past, are no longer viewed as permissible practices. Divorce is permissible, but infrequent.

Modern day

Today most Ticuna people dress in western clothing and only wear their traditional garments made out of tree bark and practice their ceremonies on special occasions or for tourists.[8] Most Ticuna nowadays are fluent in Portuguese or Spanish depending on the country that they live in,[3] and mostly use Spanish and Portuguese names. Poverty and lack of education are persistent problems in most Ticuna communities, leading to government and NGO efforts to increase educational and academic opportunities.[9][10] In December 1986 the General Organization of Bilingual Ticuna Teachers (or OGPTB in its Portuguese/Spanish abbreviation) was founded in order to provide Ticuna children with quality bilingual education and more opportunities. In 1998 there were only around 7,400 ethnic Ticuna children enrolled in elementary school, by 2005 the number has more than doubles to 16,100. Another goal of the OGPTB was the gradual replacement of non-Indigenous teaches with Ticuna ones for Ticuna students as to better provide bilingual education. By 2005 over half of the teachers where ethnic Ticuna. So effect the OGPTB program has been that it is now being expanded and copied to better serve the educational needs of other indigenous people in Brazil and Colombia.[11]

The Ticuna are also coming under increasing influence of evangelization and proselytism by Christian missionaries, which has impacted the Ticuna way of life.[12][13] Catholic,[14] Baptist,[15] Presbyterian,[16] and Evangelical[17] missionaries are all active among the Ticuna; sometimes the missionaries are ethnic Ticuna themselves.

Notes

- "Ticuna: Introduction." Povos Indígenas no Brasil. Retrieved 4 Feb 2012.

- "Ticuna." Ethnologue. Retrieved 1 Feb 2012.

- Luedtke, Jennifer Gail (1990). "Chapter 1 The Ticuna: Prehistory, History, and Language". Mitochondrial D-loop Characterization of the Amazonian Ticuna Population. Binghamton State University of New York Press: ProQuest.

- Kaufman, Terrence (1990). "Language History in South America: What we know and how to know more". In David L. Payne (ed.). Amazonian Linguistics. Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 13–74.

- "Ticuna - Religion and Expressive Culture". Countries and their Culture. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- "Ticuna Indians". Catholic Encyclopedia. New Advent. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- Dan James Patone. "Ticuana rites of passage". Amazon-Indians.org. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- "Tikuna People". Rik's Adventures. 13 April 2014. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- Paladino, Mariana (2010). "Experimentando a Diferença: Trajetórias de jovens indígenas Tikuna em escolas de Ensino Médio das cidades da região do Alto Solimões, Amazonas" (PDF). Laboratório de Pesquisas em Etnicidade, Cultura e Desenvolvimento, Museu Nacional Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro – UFRJ/ Brasil (in Portuguese). Currículo sem Fronteiras.

- Bendazzoli, Sirlene (2011). "Políticas Públicas De Educação Escolar Indígena E A Formação De Professores Ticunas No Alto Solimões/am". Currículo sem Fronteiras (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Universidade de São Paulo.

- "Educación > Ticuna". Equipe de edição da Enciclopédia Povos Indígenas no Brasil (in Spanish). June 2008. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- "Projetos em Foco - Índios Ticunas (Project in focus, evangelizing the Ticuana Indians". Missões Nacionais (in Portuguese). YouTube. 29 July 2014. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- "Encuentro Regional OFS Amazonas - Colombia 15-17 Oct. 2011". Sara I. Ruiz M. (in Spanish and Ticuna). YouTube. 30 October 2011. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- "amazonas Vídeo sobre Bautismo indìgena". YouTube. 19 December 2016.

- "Missionário Indígena da Tribo TIKUNA visita nossa Igreja (Indigenous Missionary of the Tikuna Tribe Visits Out Church)" (in Portuguese). Igreja Batista Boas Novas. 11 November 2010. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- "XXIII Conferêmoa Missionaria - Pr. Lucas Tikuna". Igreja Presbiteriana Betânia em São Francisco. YouTube. 18 August 2014. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- "show da virada! Igreja indígena evangélica filadelfia 2015". Marion Ticuna. YouTube. 1 January 2016. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

External links

- Nimuendaju, Curt (1952). "The Tukuna" (PDF). University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology. 45. Retrieved 2018-01-27.

- Sullivan, James Lamkin (1970). "The impact of education on Ticuna Indian culture: an historical and ethnographic field study". North Texas State University. Retrieved 2018-01-27. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Amazon’s Remaining Ticuna Indians Ban Tourists," Talking About Colombia

- Ticuna mask for girl's puberty ceremony, National Museum of the American Indian