Thornback guitarfish

The thornback guitarfish (Platyrhinoidis triseriata) is a species of ray in the family Platyrhinidae, and the only member of its genus. Despite its name and appearance, it is more closely related to electric rays than to true guitarfishes of the family Rhinobatidae.[2] This species ranges from Tomales Bay to the Gulf of California, generally in inshore waters no deeper than 6 m (20 ft). It can be found on or buried in sand or mud, or in and near kelp beds. Reaching 91 cm (36 in) in length, the thornback guitarfish has a heart-shaped pectoral fin disc and a long, robust tail bearing two posteriorly positioned dorsal fins and a well-developed caudal fin. The most distinctive traits of this plain-colored ray are the three parallel rows of large, hooked thorns that start from the middle of the back and run onto the tail.

| Thornback guitarfish | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Subclass: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Platyrhinoidis Garman, 1881 |

| Species: | P. triseriata |

| Binomial name | |

| Platyrhinoidis triseriata (D. S. Jordan & C. H. Gilbert, 1880) | |

| |

| Range of the thornback guitarfish[1] | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Platyrhina triseriata D. S. Jordan & Gilbert, 1880 | |

Encountered singly or in groups, the thornback guitarfish feeds on small, benthic invertebrates and bony fishes. It is aplacental viviparous, with the developing young drawing sustenance from a yolk sac. Females give birth to 1–15 pups annually in late summer, following a roughly year-long gestation period. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has listed the thornback guitarfish under Least Concern because the majority of its range lies within United States waters, where it is common since it has no commercial value and is not heavily fished commercially or recreationally. The status of this species in Mexican waters is inadequately known but may be more precarious.

Taxonomy and phylogeny

The thornback guitarfish was scientifically described by American ichthyologists David Starr Jordan and Charles Henry Gilbert in an 1880 issue of the scientific journal Proceedings of the United States National Museum. They assigned it to the genus Platyrhina, and named it triseriata from the Latin tres ("three") and series ("row"), in reference to the three rows of thorns on its back.[3][4] One year later in the same journal, Samuel Garman placed this species in a newly created genus, Platyrhinoidis.[5] The type specimen is an adult male caught off Santa Barbara on February 8, 1880.[3] Other common names for this species include banjo shark (not to be confused with the Australian banjo sharks, Trygonorrhina), California thornback, guitarfish, round skate, shovelnose, thornback, and thornback ray.[1]

Based on morphology, John McEachran and Neil Aschliman concluded in a 2004 phylogenetic study that Platyrhinoidis and Platyrhina together form the most basal clade of the order Myliobatiformes, and are thus the sister group to all other members of the order (encompassing stingrays and their relatives), rather than being closely related to the true guitarfishes of the family Rhinobatidae, a possibility that had long been considered by taxonomists.[6] Molecular phylogenetics, by contrast, consistently recovers Platyrhinidae as being a close relative of neither guitarfish nor stringrays, but rather as the sister-group to Torpediniformes, the electric rays.[2]

Description

The pectoral fin disc of the thornback guitarfish is heart-shaped, slightly longer than it is wide, and thick towards the front. The snout is short and broad, with a blunt tip protruding slightly from the disc. The eyes are small and widely spaced; the spiracles are larger than the eyes and lie closely behind. The wide nostrils are preceded by moderately large, broad flaps of skin. The mouth is wide and gently arched; there are a pair of creases running from the mouth corners to the nostrils, enclosing a roughly trapezoidal area. The lower lip is inscribed by a deep furrow that wraps around the mouth corners. The small teeth have low crowns that may be sharp to blunt, and are arranged in 68–82 rows in the upper jaw and 64–78 rows in the lower jaw. The five pairs of gill slits are small and located beneath the disc.[3][4][5]

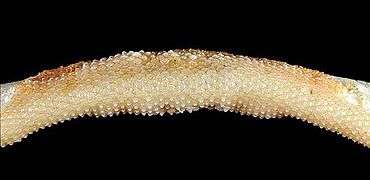

The pelvic fins have curved outer margins and angular rear tips; males have long claspers. The tail is robust and much longer than the disc, with lateral skin folds running along either side. The two dorsal fins are similar in size and shape, being longer than tall with rounded posterior margins. The first dorsal fin lies closer to the caudal fin than the pelvic fins. The caudal fin is well-developed and almost elliptical, without a distinct lower lobe. The skin is entirely covered by tiny dermal denticles; additionally there are large recurved thorns in two or three rows along the leading margin of the disc, in small groups on the snout tip, around the eyes, and on the "shoulders", and most distinctively in three rows running from the middle of the back to the second dorsal fin. This species is plain olive to grayish brown above and off-white below. The snout and disc margins are barely translucent. It grows up to 91 cm (36 in) long.[3][4][5]

Jaws

Jaws Upper teeth

Upper teeth Lower teeth

Lower teeth

Distribution and habitat

Endemic to the northeastern Pacific Ocean, the thornback guitarfish is found from Tomales Bay to Magdalena Bay, with additional isolated populations in the Gulf of California. It is reportedly very abundant in some coastal waters off California and Baja California, such as in Elkhorn Slough, and uncommon north of Monterey and in the Gulf of California.[1][4] Bottom-dwelling in nature, this species is typically found close to shore in less than 6 m (20 ft) of water, though it has been recorded from as deep as 137 m (449 ft). It inhabits coastal habitats with muddy or sandy bottoms, including bays, sloughs, beaches, and lagoons, and can also be found in kelp beds and adjacent areas.[1]

Biology and ecology

During the day, the thornback guitarfish spends much time partially buried in sediment. It may be encountered singly, in small groups, or in large aggregations that form seasonally in particular bays and sloughs. The diet of this ray consists of polychaete worms, crustaceans (including crabs, shrimps, and isopods), squids, and small bony fishes (including anchovies, sardines, gobies, sculpins, and surfperches).[1][7] It can detect prey with its electroreceptive ampullae of Lorenzini, which are most sensitive to electric fields with a frequency of 5–15 Hz.[8] In turn, the thornback guitarfish is preyed upon by sharks and the northern elephant seal (Mirounga angustirostris).[4] Known parasites of this species include the tapeworm Echinobothrium californiense[9] and the nematode Proleptus acutus.[10] Thornback guitarfish mate in late summer, and females give birth the following year at around the same time, peaking in August. It is aplacental viviparous, with developing embryos sustained until birth by yolk. Females bear litters of 1–15 pups every year; the newborn rays measure about 11 cm (4.3 in) long. Males and females reach sexual maturity at 37 and 48 cm (15 and 19 in) long respectively.[1]

Human interactions

Harmless and docile, the thornback guitarfish can be readily approached underwater, and fares well in public aquariums.[4][7] Off the United States, this ray is common and faces no substantial threats: it is only occasionally caught incidentally by commercial and recreational fishers, and has no economic value. As most of its range lies within US waters, the species has been assessed as Least Concern overall by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). However, in Mexican waters the thornback guitarfish population is small and fragmented, and the degree to which it is affected by fishing is uncertain. There, the IUCN has listed it locally under Data Deficient while noting its susceptibility to inshore lagoon fisheries and shrimp trawlers, and the urgent need for additional information to ensure its long-term regional survival.[1]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Platyrhinoidis triseriata. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Platyrhinoidis triseriata |

- Carlisle, A.B.; Garayzar, C.V. (2006). "Platyrhinoidis triseriata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2006. Retrieved October 27, 2011.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Aschliman, Neil C.; Nishida, Mutsumi; Miya, Masaki; Inoue, Jun G.; Rosana, Kerri M.; Naylor, Gavin J.P. (2012). "Body plan convergence in the evolution of skates and rays (Chondrichthyes: Batoidea)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. Elsevier BV. 63 (1): 28–42. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2011.12.012. ISSN 1055-7903.

- Jordan, D.S.; Gilbert , C.H. (May 18, 1880). "Description of a new ray (Platyrhina triseriata), from the coast of California". Proceedings of the United States National Museum. 3 (108): 36–38. doi:10.5479/si.00963801.3-108.36.

- Ebert, D.A. (2003). Sharks, Rays, and Chimaeras of California. University of California Press. pp. 188–189. ISBN 978-0-520-22265-6.

- Garman, S. (February 23, 1881). "Synopsis and descriptions of the American Rhinobatidae". Proceedings of the United States National Museum. 3 (180): 516–523. doi:10.5479/si.00963801.180.516.

- McEachran, J.D.; Aschliman, N. (2004). "Phylogeny of Batoidea". In Carrier, L.C.; Musick, J.A.; Heithaus, M.R. (eds.). Biology of Sharks and Their Relatives. CRC Press. pp. 79–113. ISBN 978-0-8493-1514-5.

- Michael, S.W. (1993). Reef Sharks & Rays of the World. Sea Challengers. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-930118-18-1.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2011). "Platyrhinoidis triseriata" in FishBase. April 2011 version.

- Ivanov, V.A.; Campbell, R.A. (May 1998). "Echinobothrium californiense n. sp. (Cestoda: Diphyllidea) from the thornback ray Platyrhinoidis triseriata (Chondrichthyes: Rajoidei) and a key to the species in the genus". Systematic Parasitology. 40 (1): 49–54. doi:10.1023/a:1005907607272.

- Specian, R.D.; Ubelaker, J.E.; Dailey, M.D. (1975). "Neoleptus gen. n. and a revision of the genus Proleptus Dujardin, 1845" (PDF). Proceedings of the Helminthological Society of Washington. 42 (1): 14–21.